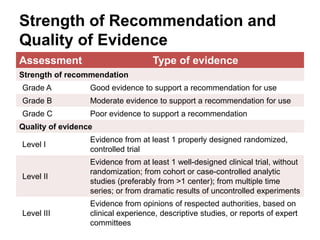

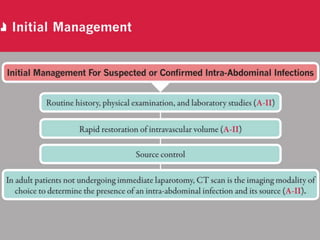

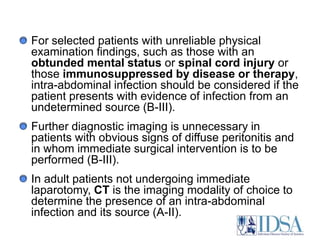

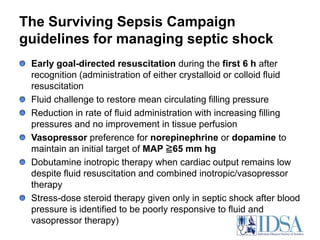

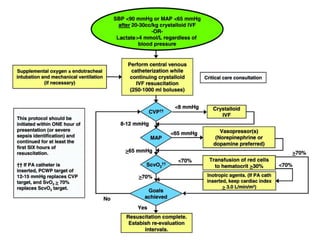

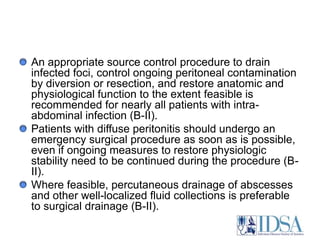

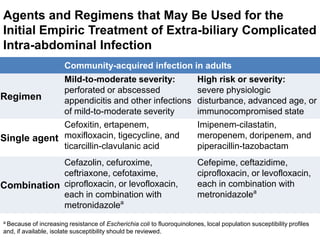

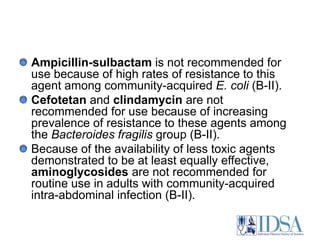

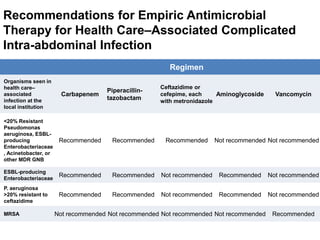

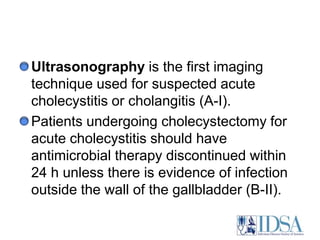

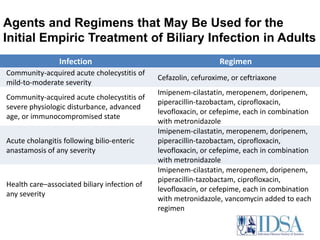

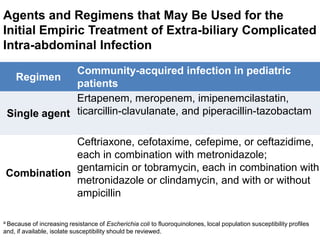

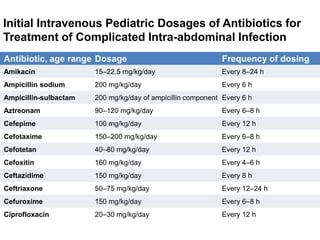

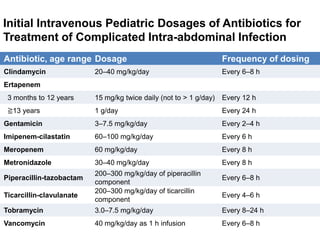

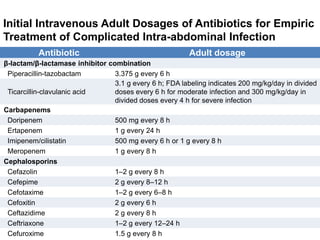

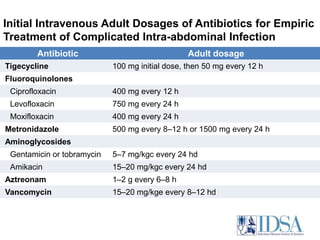

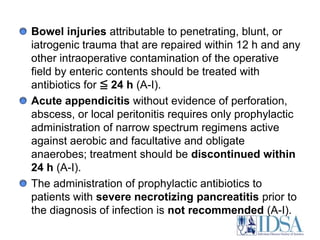

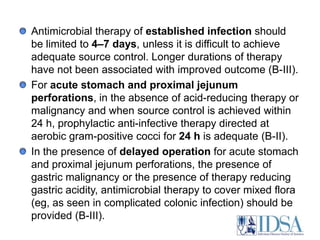

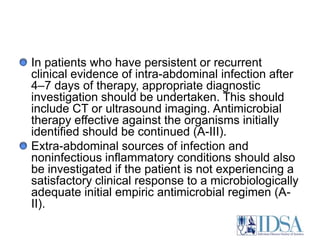

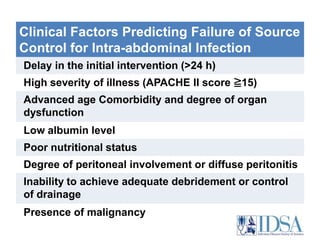

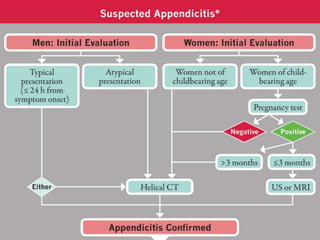

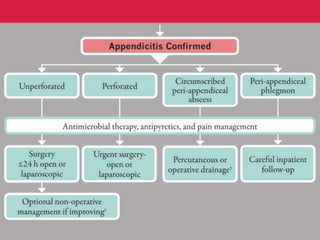

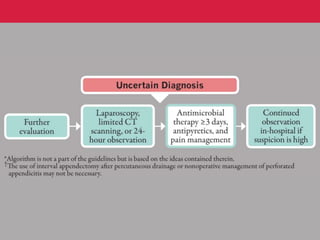

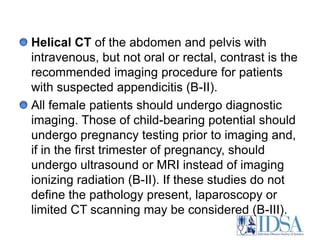

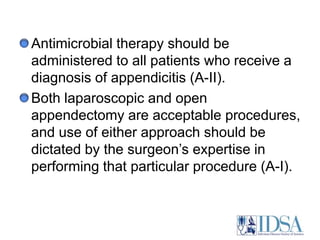

The document provides guidelines for the diagnosis and management of complicated intra-abdominal infections in adults and children, emphasizing appropriate imaging, fluid resuscitation, and initiation of antimicrobial therapy based on clinical status. It outlines early intervention strategies, source control procedures, and the use of specific antibiotic regimens while considering resistance patterns and local susceptibility profiles. Additionally, it highlights recommendations for managing acute cholecystitis, cholangitis, and appendicitis, with a focus on appropriate diagnostic imaging and timing of therapeutic interventions.