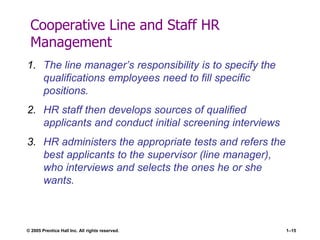

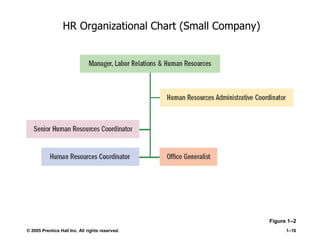

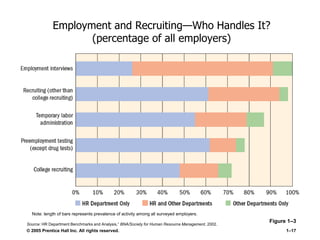

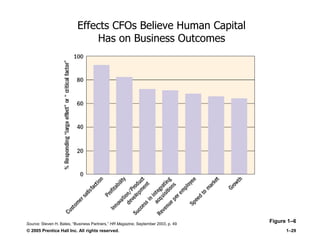

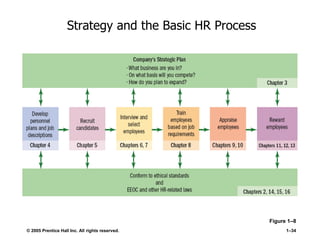

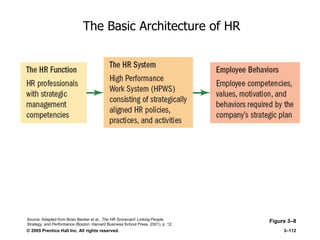

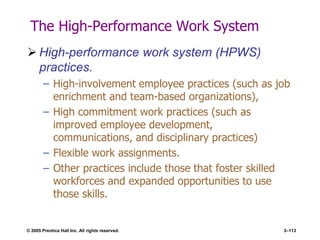

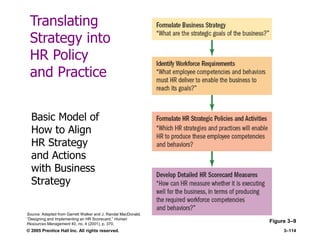

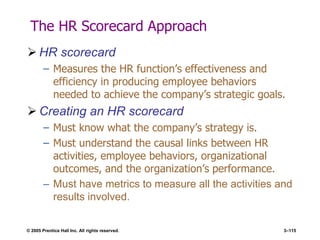

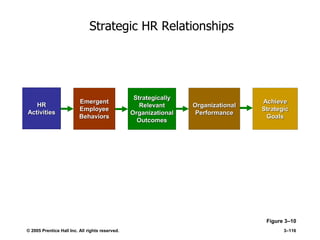

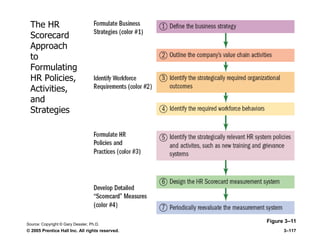

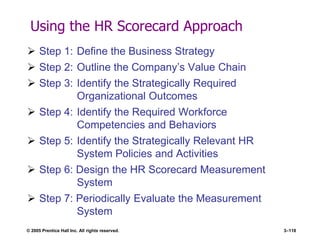

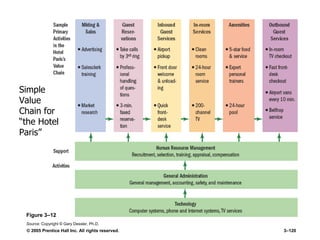

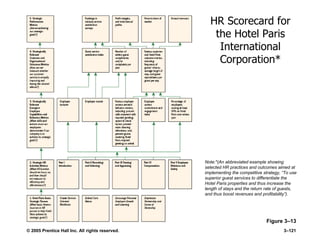

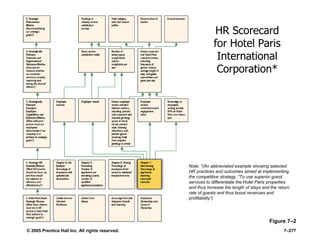

The document discusses the strategic role of human resource management. It explains that HR involves carrying out policies and practices related to recruiting, training, rewarding, and evaluating employees. The responsibilities of HR include both line managers who directly oversee employees and staff managers who assist and advise line managers. An effective HR department formulates strategy with top management and uses metrics to demonstrate how HR activities achieve strategic goals and business outcomes. The role of HR is evolving to focus more on business objectives and demonstrating return on investment through metrics like turnover and training costs.

![© 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 1–22

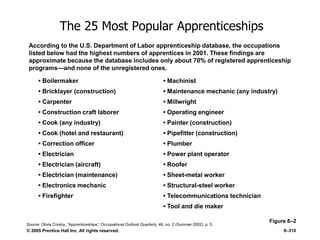

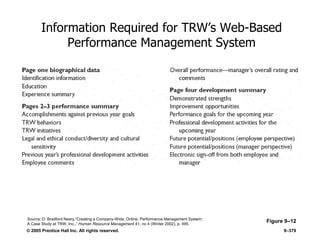

HR Metrics

Absence Rate

[(Number of days absent in month) ÷ (Average number of

employees during mo.) × (number of workdays)] × 100

Cost per Hire

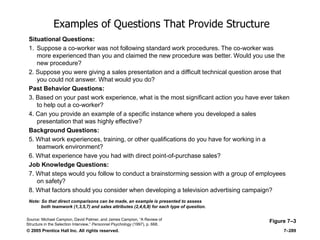

(Advertising + Agency Fees + Employee Referrals + Travel

cost of applicants and staff + Relocation costs + Recruiter

pay and benefits) ÷ Number of Hires

Health Care Costs per Employee

Total cost of health care ÷ Total Employees

HR Expense Factor

HR expense ÷ Total operating expense

Figure 1–5

Sources: Robert Grossman, ―Measuring Up,‖ HR Magazine, January 2000, pp. 29–35; Peter V. Le Blanc, Paul Mulvey, and Jude T.

Rich, ―Improving the Return on Human Capital: New Metrics,‖ Compensation and Benefits Review, January/February 2000, pp. 13–

20;Thomas E. Murphy and Sourushe Zandvakili, ―Data and Metrics-Driven Approach to Human Resource Practices: Using Customers,

Employees, and Financial Metrics,‖ Human Resource Management 39, no. 1 (Spring 2000), pp. 93–105; [HR Planning, Commerce

Clearing House Incorporated, July 17, 1996;] SHRM/EMA 2000 Cost Per Hire and Staffing Metrics Survey; www.shrm.org.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hrmslides-160331152211/85/Hrm-slides-22-320.jpg)

![© 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 1–23

HR Metrics (cont’d)

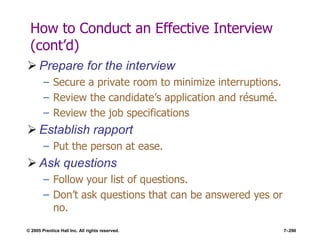

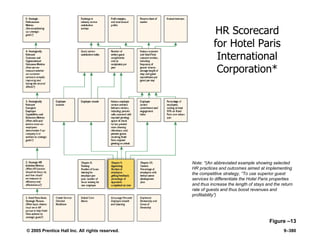

Human Capital ROI

Revenue − (Operating Expense − [Compensation cost +

Benefit cost]) ÷ (Compensation cost + Benefit cost)

Human Capital Value Added

Revenue − (Operating Expense − ([Compensation cost +

Benefit Cost]) ÷ Total Number of FTE

Revenue Factor

Revenue ÷ Total Number of FTE

Time to fill

Total days elapsed to fill requisitions ÷ Number hired

Figure 1–5 (cont’d)

Sources: Robert Grossman, ―Measuring Up,‖ HR Magazine, January 2000, pp. 29–35; Peter V. Le Blanc, Paul Mulvey,

and Jude T. Rich, ―Improving the Return on Human Capital: New Metrics,‖ Compensation and Benefits Review,

January/February 2000, pp. 13–20;Thomas E. Murphy and Sourushe Zandvakili, ―Data and Metrics-Driven Approach to

Human Resource Practices: Using Customers, Employees, and Financial Metrics,‖ Human Resource Management 39,

no. 1 (Spring 2000), pp. 93–105; [HR Planning, Commerce Clearing House Incorporated, July 17, 1996;] SHRM/EMA

2000 Cost Per Hire and Staffing Metrics Survey; www.shrm.org.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hrmslides-160331152211/85/Hrm-slides-23-320.jpg)

![© 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 1–24

HR Metrics (cont’d)

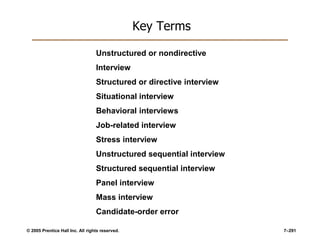

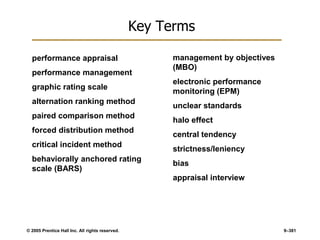

Training Investment Factor

Total training cost ÷ Headcount

Turnover Costs

Cost to terminate + Cost per hire + Vacancy Cost + Learning

curve loss

Turnover Rate

[Number of separations during month ÷ Average number of

employees during month] × 100

Workers’ Compensation Cost per Employee

Total WC cost for Year ÷ Average number of employees

Figure 1–5 (cont’d)

Sources: Robert Grossman, ―Measuring Up,‖ HR Magazine, January 2000, pp. 29–35; Peter V. Le Blanc, Paul Mulvey,

and Jude T. Rich, ―Improving the Return on Human Capital: New Metrics,‖ Compensation and Benefits Review,

January/February 2000, pp. 13–20;Thomas E. Murphy and Sourushe Zandvakili, ―Data and Metrics-Driven Approach to

Human Resource Practices: Using Customers, Employees, and Financial Metrics,‖ Human Resource Management 39,

no. 1 (Spring 2000), pp. 93–105; [HR Planning, Commerce Clearing House Incorporated, July 17, 1996;] SHRM/EMA

2000 Cost Per Hire and Staffing Metrics Survey; www.shrm.org.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hrmslides-160331152211/85/Hrm-slides-24-320.jpg)

![© 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 10–409

Identify Your Career Anchors

Career anchor

– A concern or value that a person you will not give

up if a [career] choice has to be made.

Typical career anchors

– Technical/functional competence

– Managerial competence

– Creativity

– Autonomy and independence

– Security](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hrmslides-160331152211/85/Hrm-slides-409-320.jpg)

![© 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 16–680

OSHA Standards Examples

Figure 16–1

Guardrails not less than 2″ × 4″ or the equivalent

and not less than 36″ or more than 42″ high, with a

midrail, when required, of a 1″ × 4″ lumber or

equivalent, and toeboards, shall be installed at all

open sides on all scaffolds more than 10 feet above

the ground or floor.

Toeboards shall be a minimum of 4″ in height.

Wire mesh shall be installed in accordance with

paragraph [a] (17) of this section.

Source: General Industry Standards and Interpretations, U.S. Department of Labor,

OSHA (Volume 1: Revised 1989, Section 1910.28(b) (15)), p. 67.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hrmslides-160331152211/85/Hrm-slides-680-320.jpg)

![© 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 17–741

Five Factors

Important in

International

Assignee

Success,

and Their

Components

Figure 17–1

I. Job Knowledge

and Motivation

Managerial ability

Organizational ability

Imagination

Creativity

Administrative skills

Alertness

Responsibility

Industriousness

Initiative and energy

High motivation

Frankness

Belief in mission and job

Perseverance

II. Relational Skills

Respect

Courtesy and fact

Display of respect

Kindness

Empathy

Non-judgmentalness

Integrity

Confidence

III. Flexibility/Adaptability

Resourcefulness

Ability to deal with stress

Flexibility

Emotional stability

Willingness to change

Tolerance for ambiguity

Adaptability

Independence

Dependability

Political sensitivity

Positive self-image

IV. Extracultural Openness

Variety of outside interests

Interest in foreign cultures

Openness

Knowledge of local language[s]

Outgoingness and extroversion

Overseas experience

V. Family Situation

Adaptability of spouse

and family

Spouse’s positive opinion

Willingness of spouse to

live abroad

Stable marriage

Source: Adapted from Arthur Winfred Jr., and Winston Bennett Jr., ―The

International Assignee: The Relative Importance of Factors Perceived to

Contribute to Success,‖ Personnel Psychology 18 (1995), pp. 106–107.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hrmslides-160331152211/85/Hrm-slides-741-320.jpg)