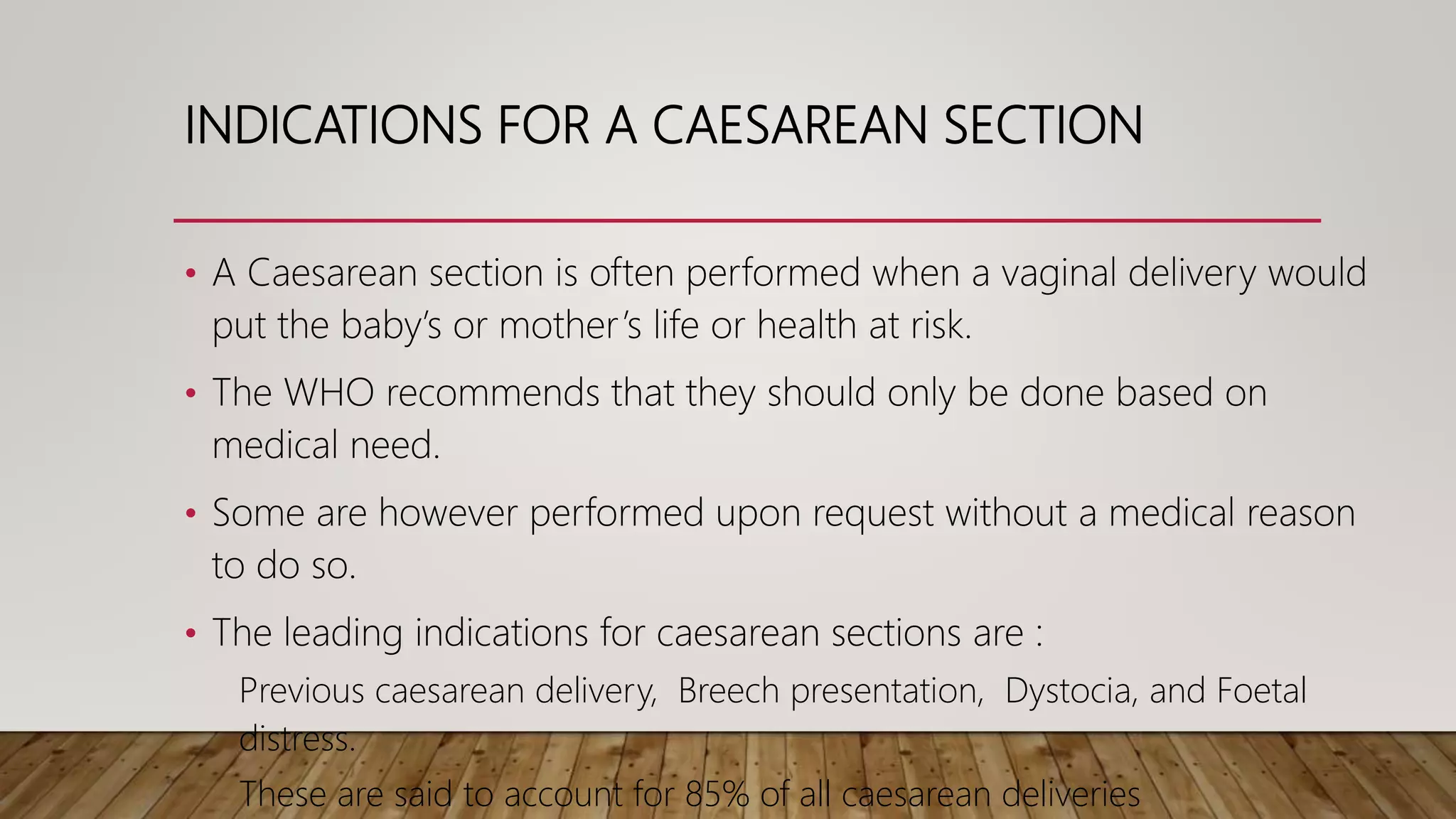

This document discusses caesarean section, including indications, classifications, steps, complications, and concerns. It begins with an introduction noting that caesarean section rates have risen globally in recent decades. The main indications for caesarean section are then outlined, including previous c-section, breech presentation, dystocia, and fetal distress. The document proceeds to describe the classification, preoperative management, technique, postoperative care, complications, and concerns regarding overuse of c-section.