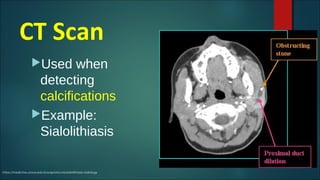

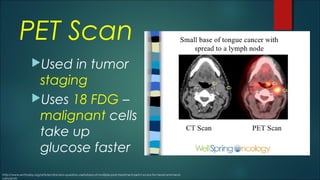

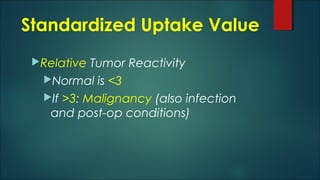

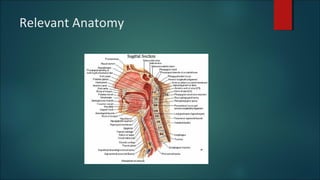

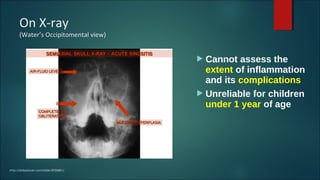

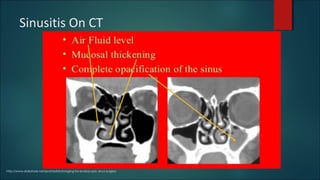

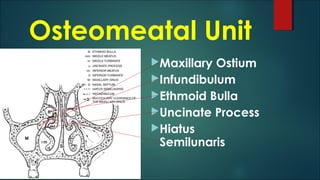

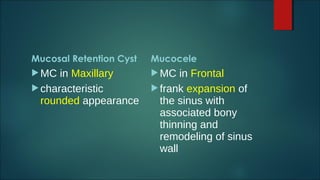

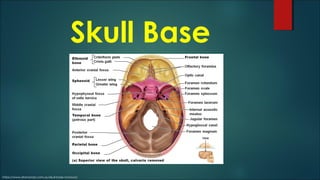

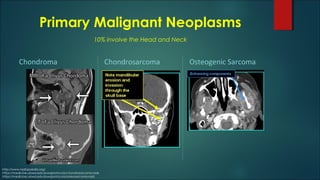

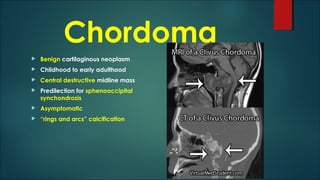

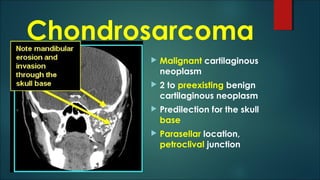

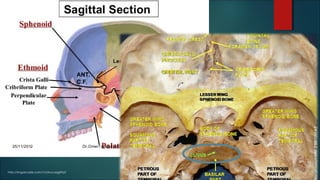

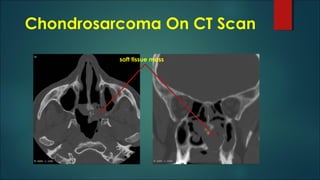

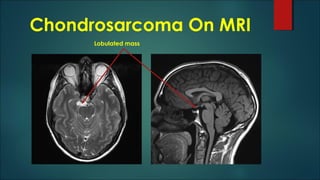

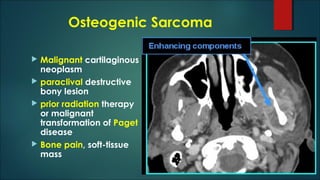

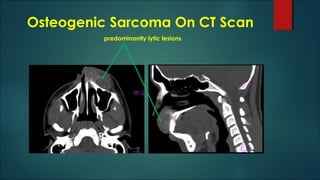

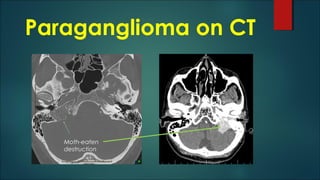

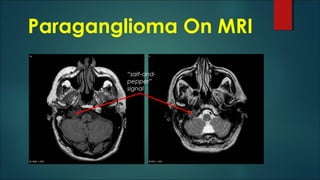

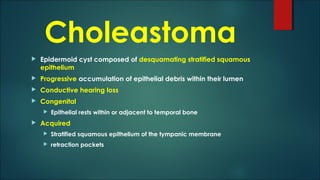

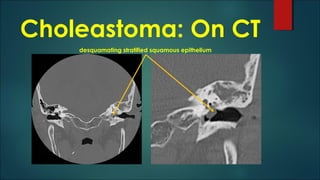

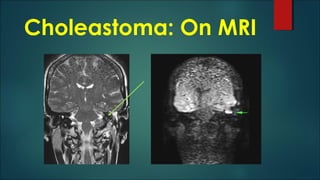

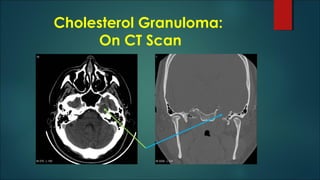

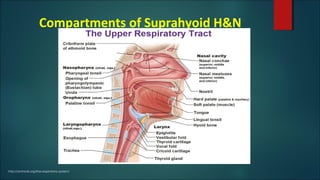

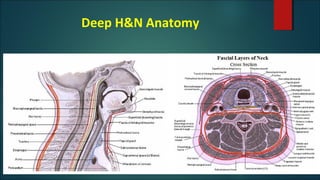

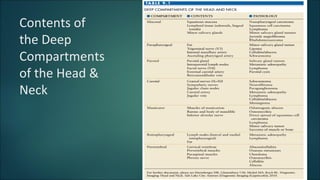

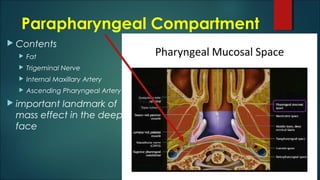

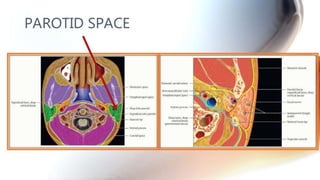

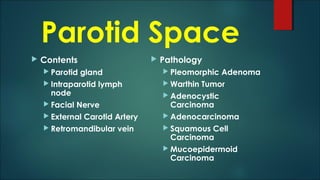

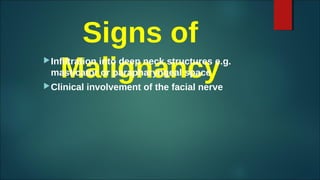

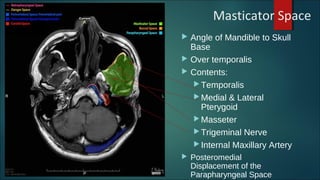

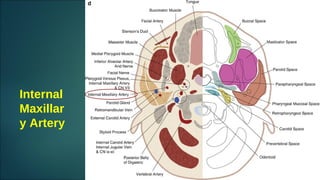

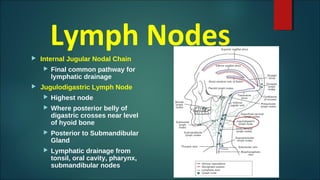

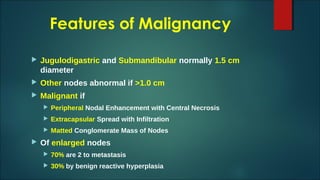

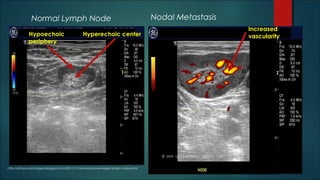

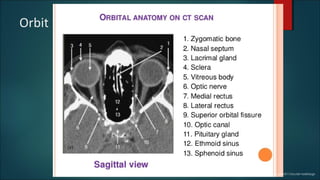

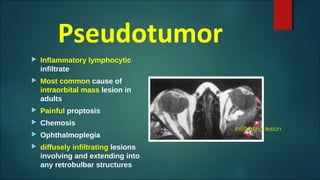

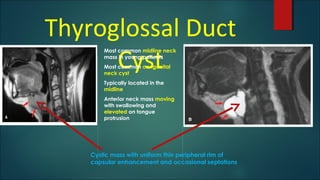

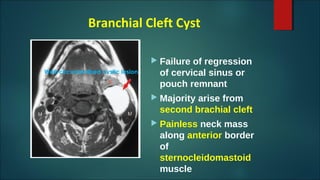

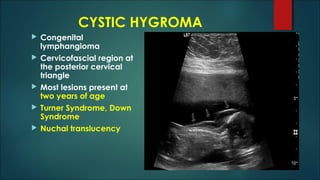

This document discusses head and neck imaging modalities and anatomy. It provides examples of different pathologies visualized on various imaging modalities like CT, MRI, PET. It describes the paranasal sinuses, skull base, compartments of the neck, and contents of each. Examples of lesions discussed include sinusitis, meningiomas, sarcomas, paragangliomas, cholesteatomas, and lymph nodes. Congenital lesions like thyroglossal duct cysts, branchial cleft cysts, and cystic hygromas are also summarized.