The document discusses the hammerhead ribozyme (HHR), a catalytic RNA, highlighting its discovery, structure, and enzymatic properties. It reviews its significance in RNA catalysis and gene regulation, detailing various studies on its mechanics and efficiency compared to protein enzymes. The document serves as a comprehensive overview of HHR's role in biological contexts and its potential applications in biotechnology.

![8

THE FULL-LENGTH SEQUENCE

At the time of HHR discovery, it was observed to be embedded within a 370 nucleotide single-

stranded genomic satellite RNA, most of which could be deleted while preserving the RNA’s

catalytic properties. Eventually, it was found that about 13 core nucleotides and a minimal

number of flanking helical nucleotides were all that was required for a respectable catalytic

turnover rate of 1 to 10 min−1

, and this “minimal” hammerhead construct became the focus of

attention. It thus came as a great surprise to most in the field when in 2003 it was finally

discovered that for optimal activity the hammerhead ribozyme in actuality requires the

presence of sequences in stem(s) I and II. These sequences interact to form tertiary contacts

(Fig. 1.1C), but were removed in the process of eliminating seemingly superfluous sequences

from the hammerhead ribozyme; the standard reductionist approach often employed in

molecular biology. Once the full ramifications of this revelation became apparent, that is, that

the entire field had been studying the residual catalytic activity of an overzealously truncated

version of the fulllength ribozyme, attention shifted away from the minimal constructs. It also

quickly became apparent that a crystal structure of the full-length hammerhead ribozyme, in

which these distal tertiary contacts were present, might be of considerable interest.

BIOLOGICAL CONTEXT

Apparently, all naturally occurring, biologically active hammerhead RNA sequences possess a

tertiary contact that enhances their ability to fold into a catalytically competent structure.

ENZYMOLOGY

Many of the biochemical experiments designed to probe the nature of catalysis in the minimal

hammerhead ribozyme structure attempted to measure the effects of structural alterations upon

the rate-limiting step (presumed to be the chemical step) of the self-cleavage reaction. In

general, the observations made in the context of the minimal hammerhead ribozyme are also

relevant to the full-length hammerhead. The most direct explanation of this fact is that both the

minimal and full-length hammerhead structures are believed to pass through what is essentially

the same transition state. The full-length hammerhead is thus believed to accelerate the self-

cleavage reaction primarily by stabilizing the precatalytic structure in a manner that is

unavailable to the minimal hammerhead due to a lack of the tertiary contact between stem(s) I

and II. The hammerhead ribozyme sequence derived from Schistosoma Sma1 is arguably the

most extensively characterized of full-length hammerhead sequences. The cleavage kinetics

and internal equilibrium have been thoroughly investigated, revealing significant surprises. The

apparent cleavage rate at pH 8.5 in 200 mM Mg2+

is at least 870 min−1

, which in actuality is a

lower bound as there is also a significant rate of ligation under these conditions. In contrast to

minimal hammerheads that show a log-linear dependence of rate on pH up to about pH 8.5, the

Sma1 hammerhead has a lower apparent pKa that is dependent upon Mg2+

concentration. At

100 mM Mg2+, the apparent pKa is about 7.5–8. The Sma1 hammerhead is also a rather

efficient ligase, revealing internal equilibrium constants (Kint1/4[EP]/[ES]) as small as 0.5 in

the presence of high concentrations of Mg2+, and as small as 1.3 under physiological

concentrations of Mg2+. Cleavage and ligation reaction rates are also highly dependent upon

the identity of the divalent cation present, with Mn2+

accelerating the reaction almost two orders](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hammerheadribozyme-170819041510/85/Hammerhead-ribozyme-9-320.jpg)

![23

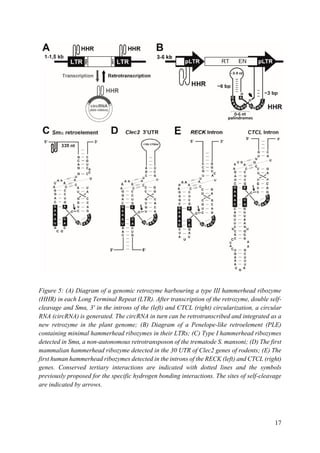

helix I (from 150 to 1500 nt, depending on the mammalian species) (Figure 5D). Although the

biological function of this self-cleaving motif is still unknown, a role in the control of the site

of polyadenylation could be suggested. In 2010, very similar type I HHRs were found

conserved in the introns of some genes of all amniotes analysed (reptiles, birds and mammals)

(Figure 5E). As the most striking case, one of these intronic HHRs was found totally conserved

in the RECK gene of all warm-blooded animals (birds and mammals), whereas some other

HHR motifs mapped in the introns of the CTCL gene of most mammals or the DTNB gene of

birds and reptiles, suggesting a role in the biogenesis of the mRNAs harbouring these

ribozymes. The high sequence and structural similarity between intronic HHRs in amniotes

and those found in the retroelements of diverse metazoans from trematodes to lower

vertebrates, such as coelacanth fishes or amphibians, suggests that these ribozymes would have

been domesticated during evolution to perform new and conserved functions in complex

metazoans such as amniotes. As a feasible hypothesis, highly conserved HHRs in the introns

of diverse genes of amniotes could represent a new form or regulation of the alternative

splicing, which in some cases may result in the production of crucial gene isoforms for these

organisms. Most likely, future bioinformatic analysis will reveal more examples of genomic

HHRs conserved either in different non-coding regions, which will help us to better understand

all the capabilities of these small ribozymes as gene regulatory elements.

CONCLUSION

The current age of genomics has opened many new entrances in the biological knowledge, and

one of these is the renaissance of the interest in self-cleaving ribozymes and RNA catalysis in

general. The extreme simplicity and little sequence conservation of small ribozymes, together

with the huge sequence space available for bioinformatics searches, make the identification of

these small motifs a hard task, usually hindered by a large collection of false positives, which

require more detailed evolutionary and/or structural analyses to be filtered out. Hence, the

hammerhead ribozyme appears to reside in an important regulatory region that provides the

possibility that the ribozyme itself can be regulated. More recent findings have demonstrated

that the hammerhead ribozyme sequence is found to be ubiquitous throughout the tree of life

and is possibly the most common ribozyme sequence apart from RNase P and the peptidyl

transferase of the ribosome. The recent discoveries of totally new self-cleaving motifs indicate

that it is just a beginning of knowing about the ribozyme and we have to go long way to

understand their importance.

REFERENCE

1. Hammann, C.; Westhof, E. Searching genomes for ribozymes and riboswitches. Genome Biol.

2007, 8, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

2. De la Peña, M.; García-Robles, I. Ubiquitous presence of the hammerhead ribozyme motif

along the tree of life. RNA 2010, 16, 1943–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

3. Jimenez, R.M.; Delwart, E.; Lupták, A. Structure-based search reveals hammerhead ribozymes

in the human microbiome. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 7737–7743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[PubMed]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hammerheadribozyme-170819041510/85/Hammerhead-ribozyme-24-320.jpg)

![24

4. Perreault, J.; Weinberg, Z.; Roth, A.; Popescu, O.; Chartrand, P.; Ferbeyre, G.; Breaker, R.R.

Identification of hammerhead ribozymes in all domains of life reveals novel structural

variations. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011, 7, e1002031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

5. Seehafer, C.; Kalweit, A.; Steger, G.; Gräf, S.; Hammann, C. From alpaca to zebrafish:

Hammerhead ribozymes wherever you look. RNA 2011, 17, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

6. De la Peña, M.; García-Robles, I. Intronic hammerhead ribozymes are ultraconserved in the

human genome. EMBO Rep. 2010, 11, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

7. Cervera, A.; Urbina, D.; De la Peña, M. Retrozymes are a unique family of non-autonomous

retrotransposons with hammerhead ribozymes that propagate in plants through circular RNAs.

Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

8. Evgen’ev, M.B.; Zelentsova, H.; Shostak, N.; Kozitsina, M.; Barskyi, V.; Lankenau, D.H.;

Corces, V.G. Penelope, a new family of transposable elements and its possible role in hybrid

dysgenesis in Drosophila virilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 196–201. [Google

Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

9. Gladyshev, E.A.; Arkhipova, I.R. Telomere-associated endonuclease-deficient Penelope-like

retroelements in diverse eukaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 9352–9357.

10. Ruminski, D.J.; Webb, C.H.; Riccitelli, N.J.; Lupták, A. Processing and translation initiation of

non-long terminal repeat retrotransposons by hepatitis delta virus (HDV)-like self-cleaving

ribozymes. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 41286–41295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

11. Eickbush, D.G.; Eickbush, T.H. R2 retrotransposons encode a self-cleaving ribozyme for

processing from an rRNA cotranscript. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010, 30, 3142–3150. [Google Scholar]

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

12. Kennell, J.C.; Saville, B.J.; Mohr, S.; Kuiper, M.T.; Sabourin, J.R.; Collins, R.A.; Lambowitz,

A.M. The VS catalytic RNA replicates by reverse transcription as a satellite of a retroplasmid.

Genes Dev. 1995, 9, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

13. Martick, M.; Horan, L.H.; Noller, H.F.; Scott, W.G. A discontinuous hammerhead ribozyme

embedded in a mammalian messenger RNA. Nature 2008, 454, 899–902. [Google Scholar]

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

14. Scott, W.G.; Horan, L.H.; Martick, M. The hammerhead ribozyme: Structure, catalysis, and

gene regulation. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2013, 120, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

15. García-Robles, I.; Sánchez-Navarro, J.; De la Peña, M. Intronic hammerhead ribozymes in

mRNA biogenesis. Biol. Chem. 2012, 393, 1317–1326.

16. Marcos de la Peña, Inmaculada García-Robles and Amelia Cervera. The Hammerhead

Ribozyme: A Long History for a Short RNA. Molecules 2017, 22(1), 78.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hammerheadribozyme-170819041510/85/Hammerhead-ribozyme-25-320.jpg)