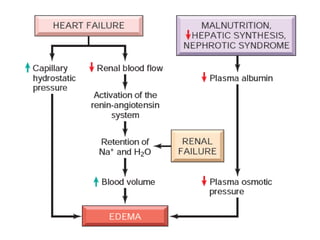

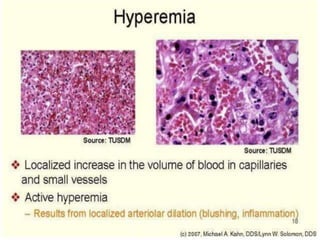

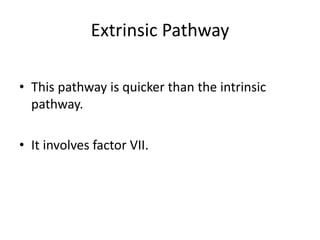

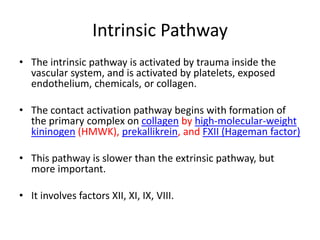

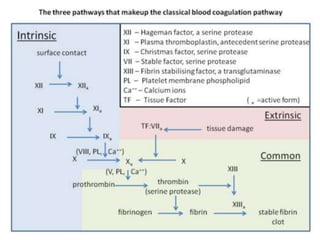

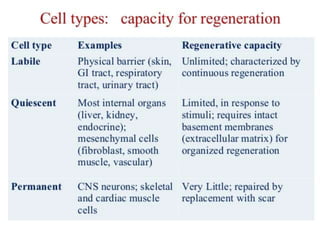

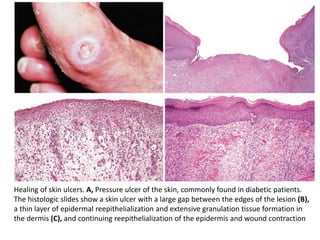

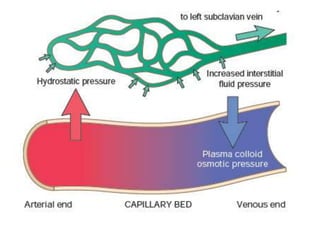

The document discusses the mechanisms of edema and fluid accumulation in tissues caused by various hemodynamic disorders, including issues with hydrostatic pressure and plasma oncotic pressure. It details the differences between inflammatory and non-inflammatory edema, along with causes such as heart failure and renal dysfunction, and explores the mechanisms of hemostasis and thrombosis in the context of vascular injury. Additionally, it covers tissue repair processes, including primary and secondary healing, and factors influencing tissue repair outcomes.

![Increased Hydrostatic Pressure

• Increases in hydrostatic pressure are mainly

caused by disorders that impair venous return.

• If the impairment is localized (e.g., a deep venous

thrombosis [DVT] in a lower extremity), then the

resulting edema is confined to the affected part.

• Conditions leading to systemic increases in

venous pressure e.g., congestive heart failure, are

understandably associated with more widespread

edema.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/haemodynamics-211024155123/85/Haemodynamics-7-320.jpg)