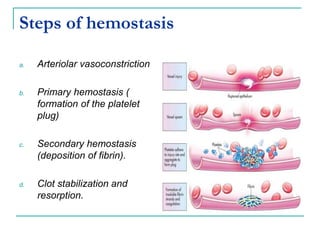

This document discusses hemodynamic disorders and provides details on several topics:

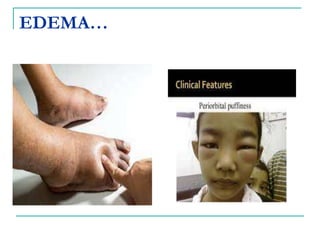

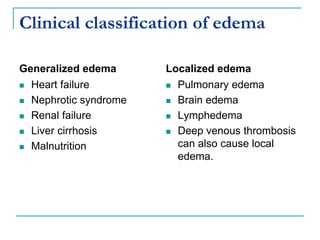

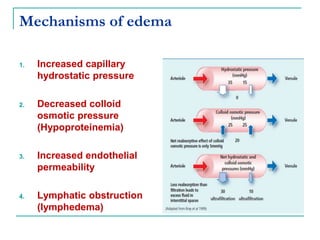

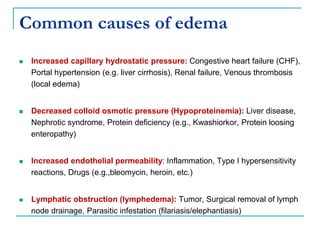

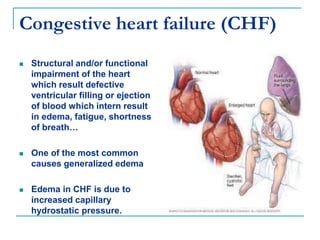

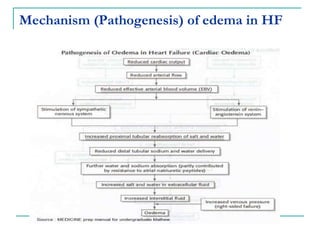

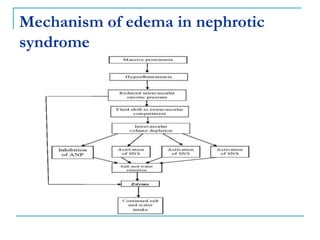

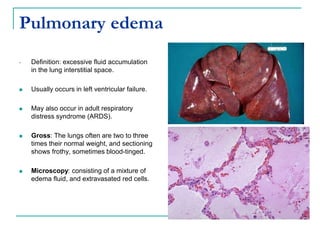

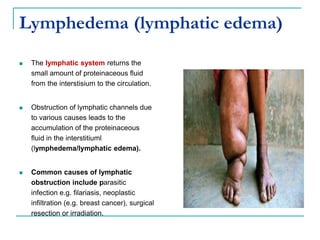

1. It defines edema as excess fluid in the interstitial space and describes different types of edema like pulmonary and brain edema.

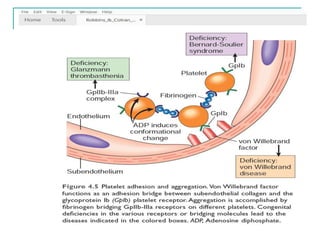

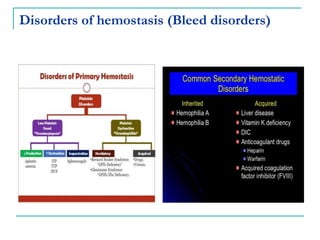

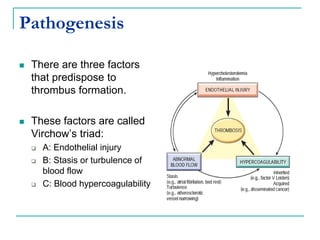

2. It explains thrombosis as the pathologic formation of an intravascular blood clot, which most commonly occurs in the deep veins of the leg. The pathogenesis of thrombosis involves endothelial injury, turbulence or stasis of blood flow, and hypercoagulability.

3. Locations of thrombus formation are discussed, noting the most common sites for arterial thrombi like the coronary and cerebral arteries, and venous thrombi which most often affect the lower extremities.

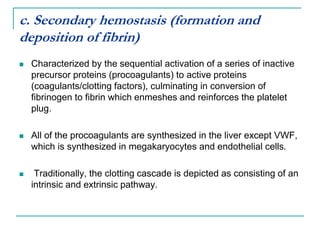

![C: Hypercoagulablity

Hypercoagulability is any alteration of the coagulation

pathway that predisposes to thrombosis.

Hypercoagulability is a less common cause of

thrombosis & it can be divided into:

a. Primary (Genetic): Mutations in factor V[Lieden factor], Anti

thrombin III deficiency, Protein C or S deficiency…

b. Acquired: Prolonged bed rest or immobilization, Myocardial

infarction, Atrial fibrillation, Tissue injury (surgery, fracture,

burn), Cancer](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hemodynamicdisorders-240316140414-c36f9513/85/HEMODYNAMIC-DISORDERS-pptx-HAWASSA-UNIVERSITY-42-320.jpg)