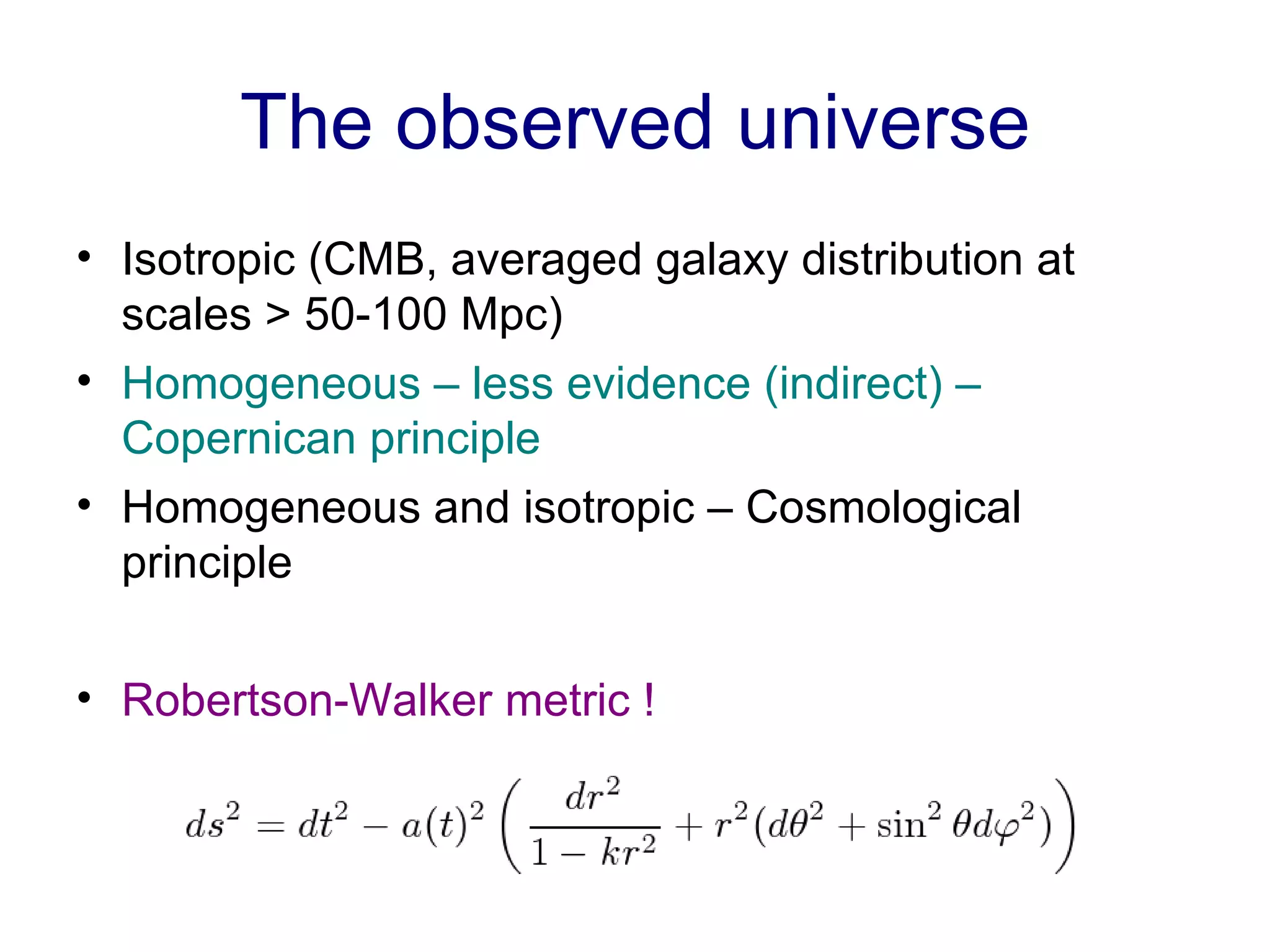

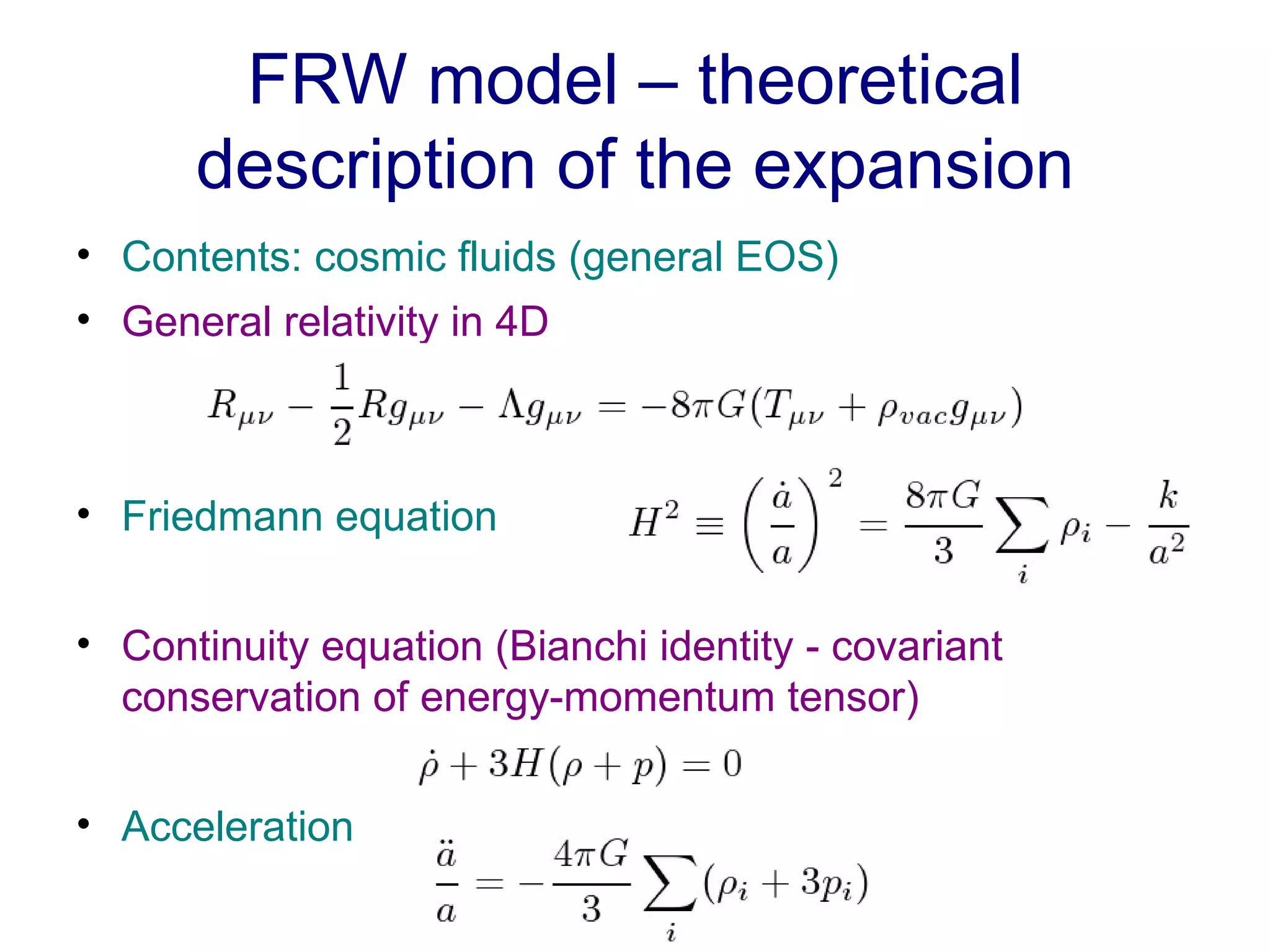

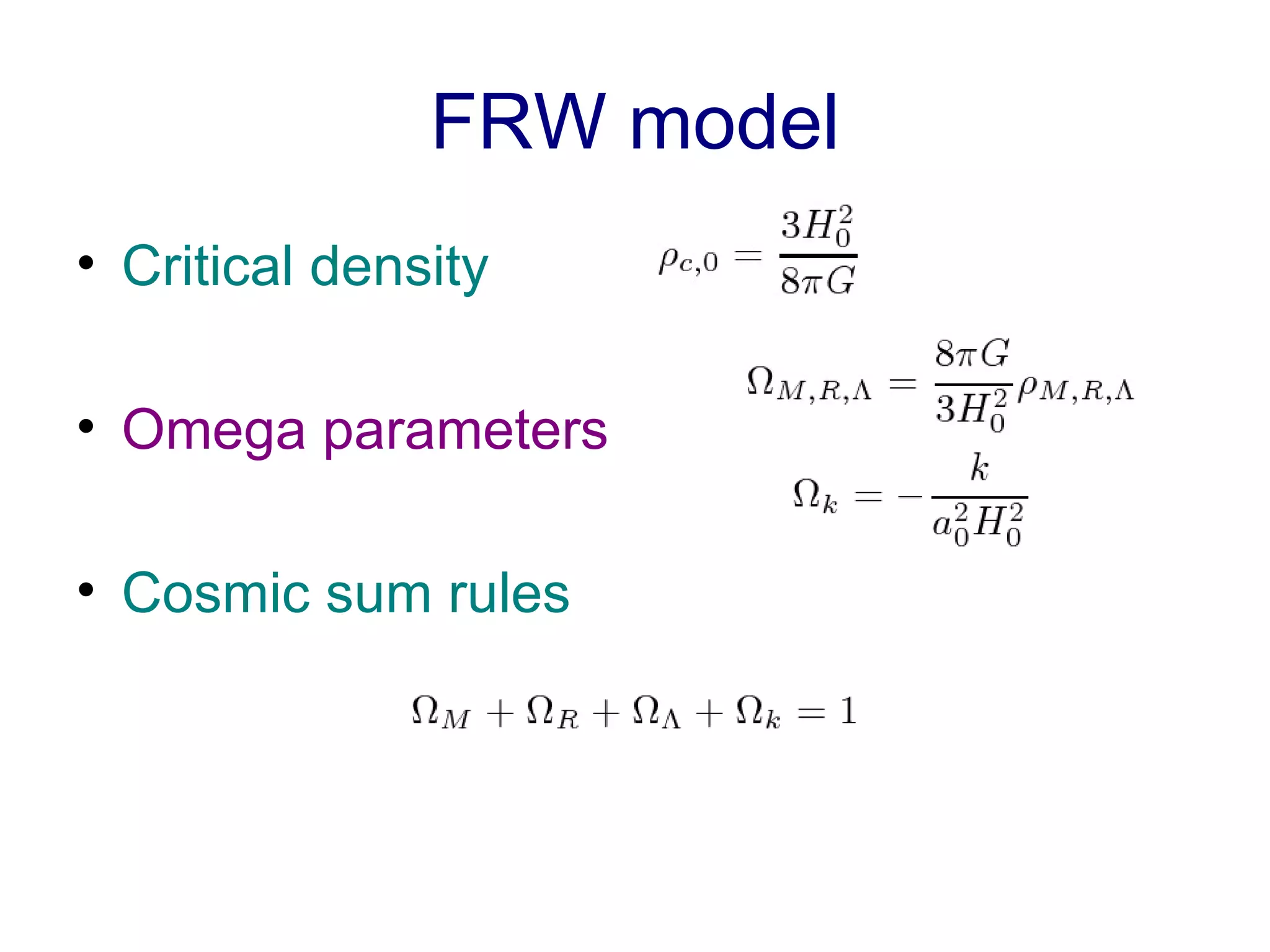

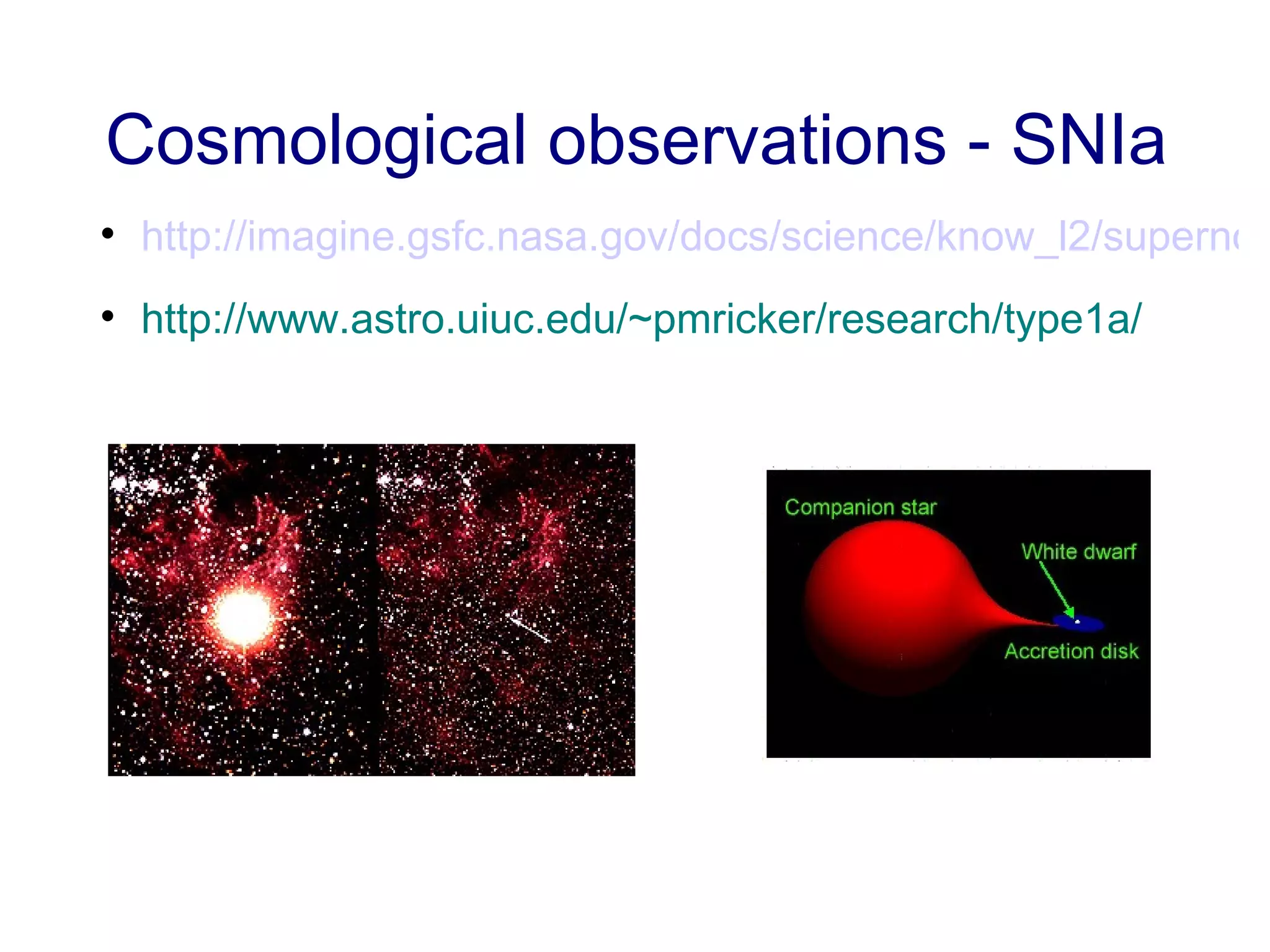

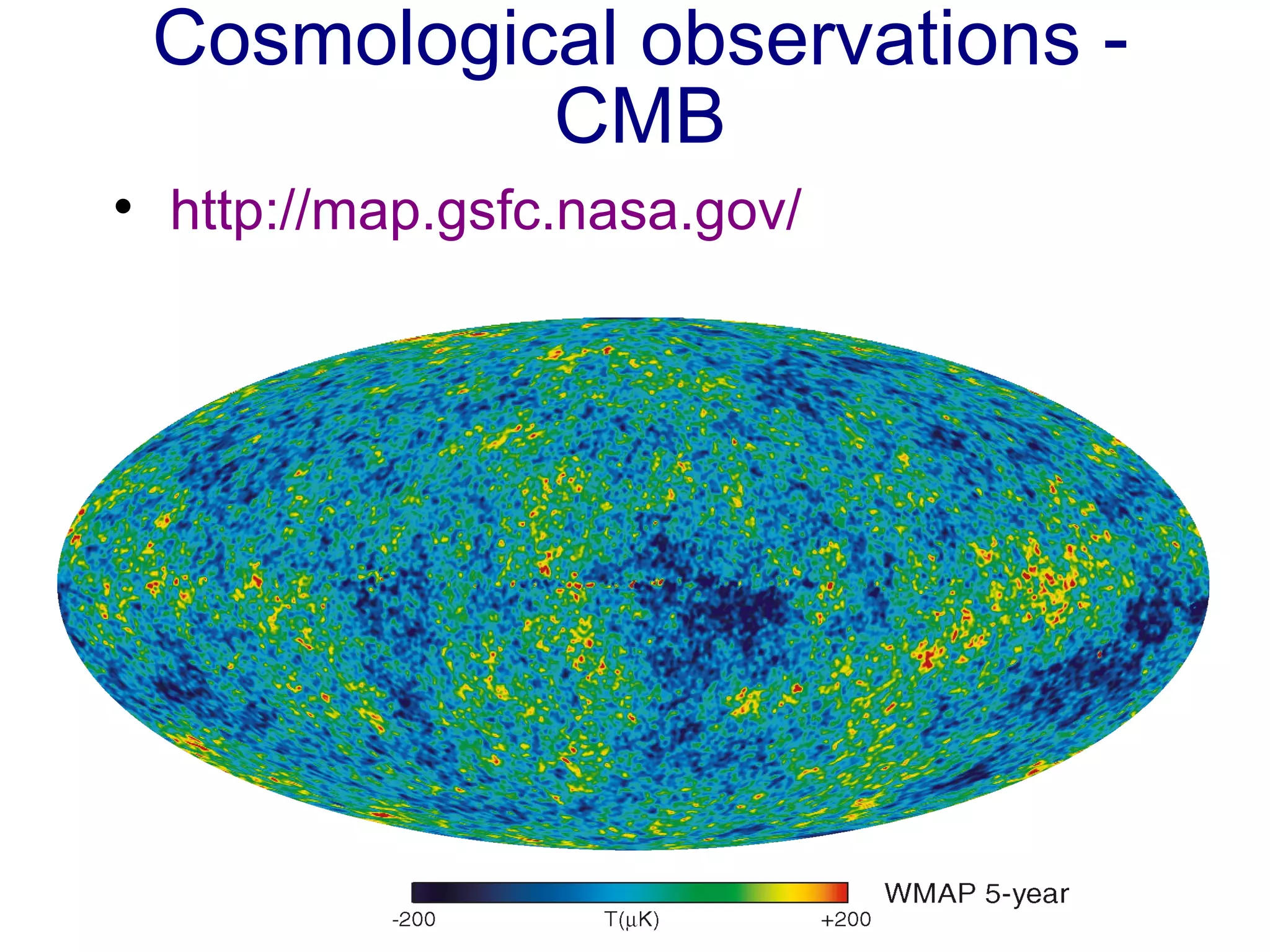

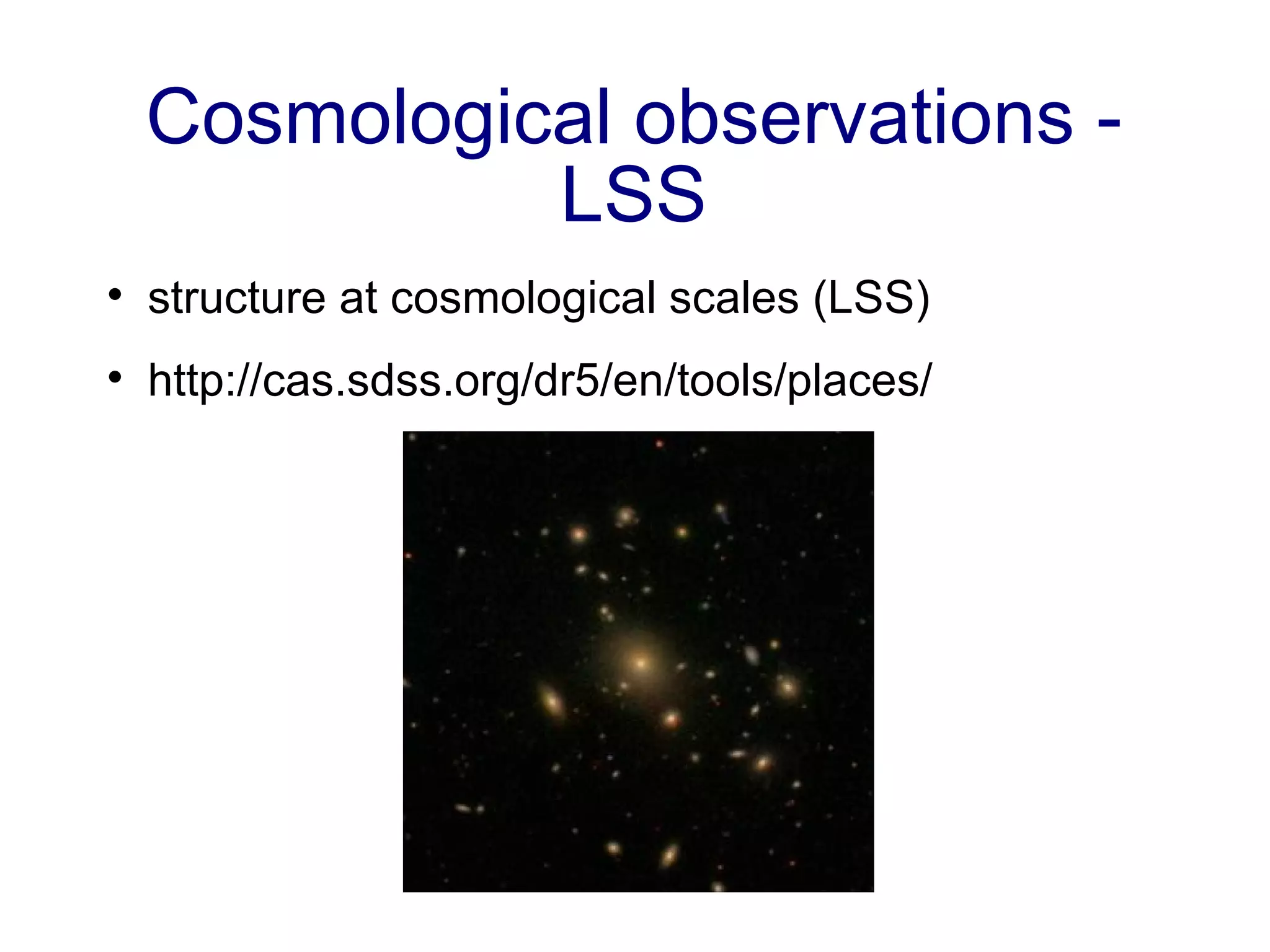

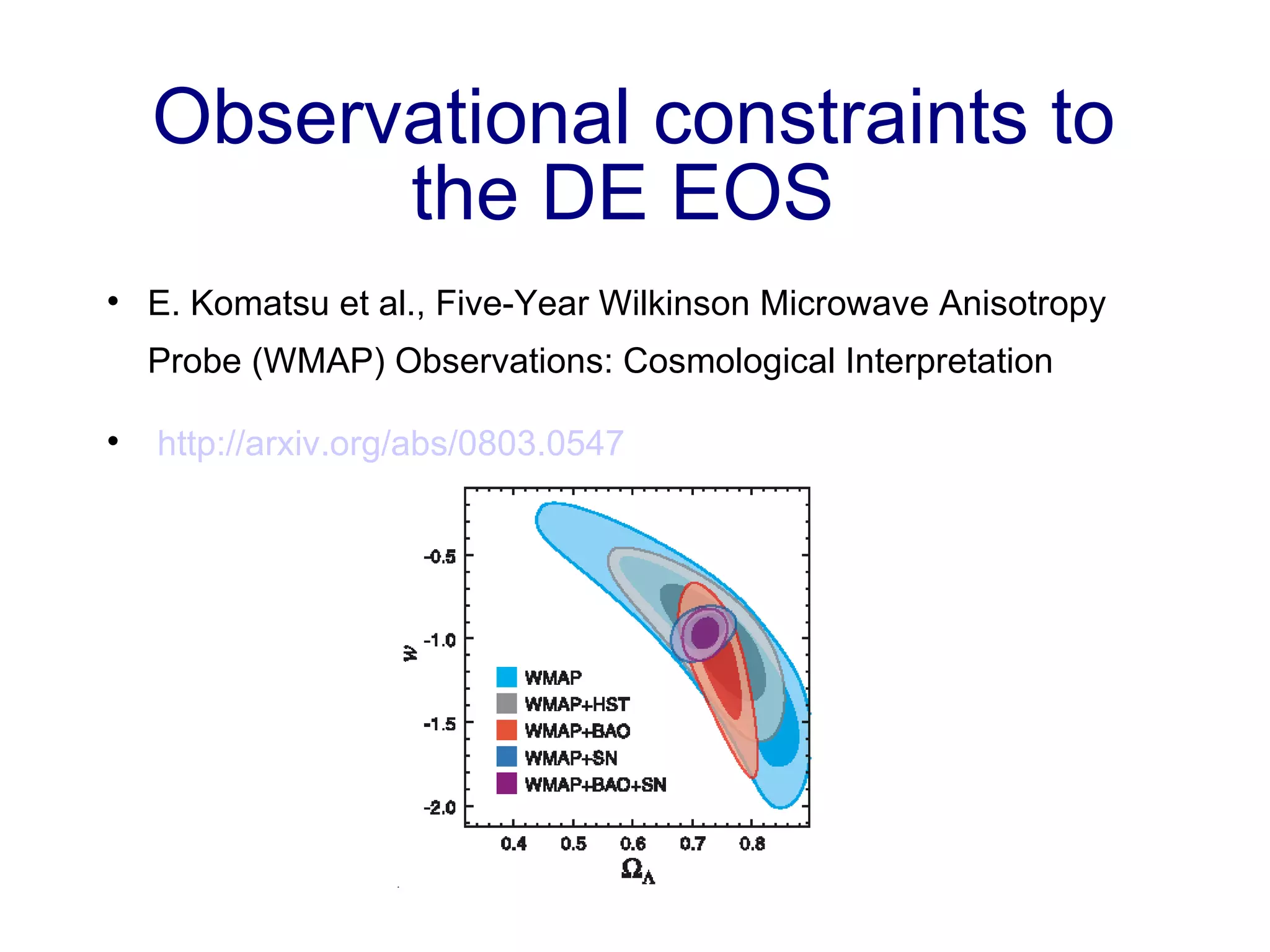

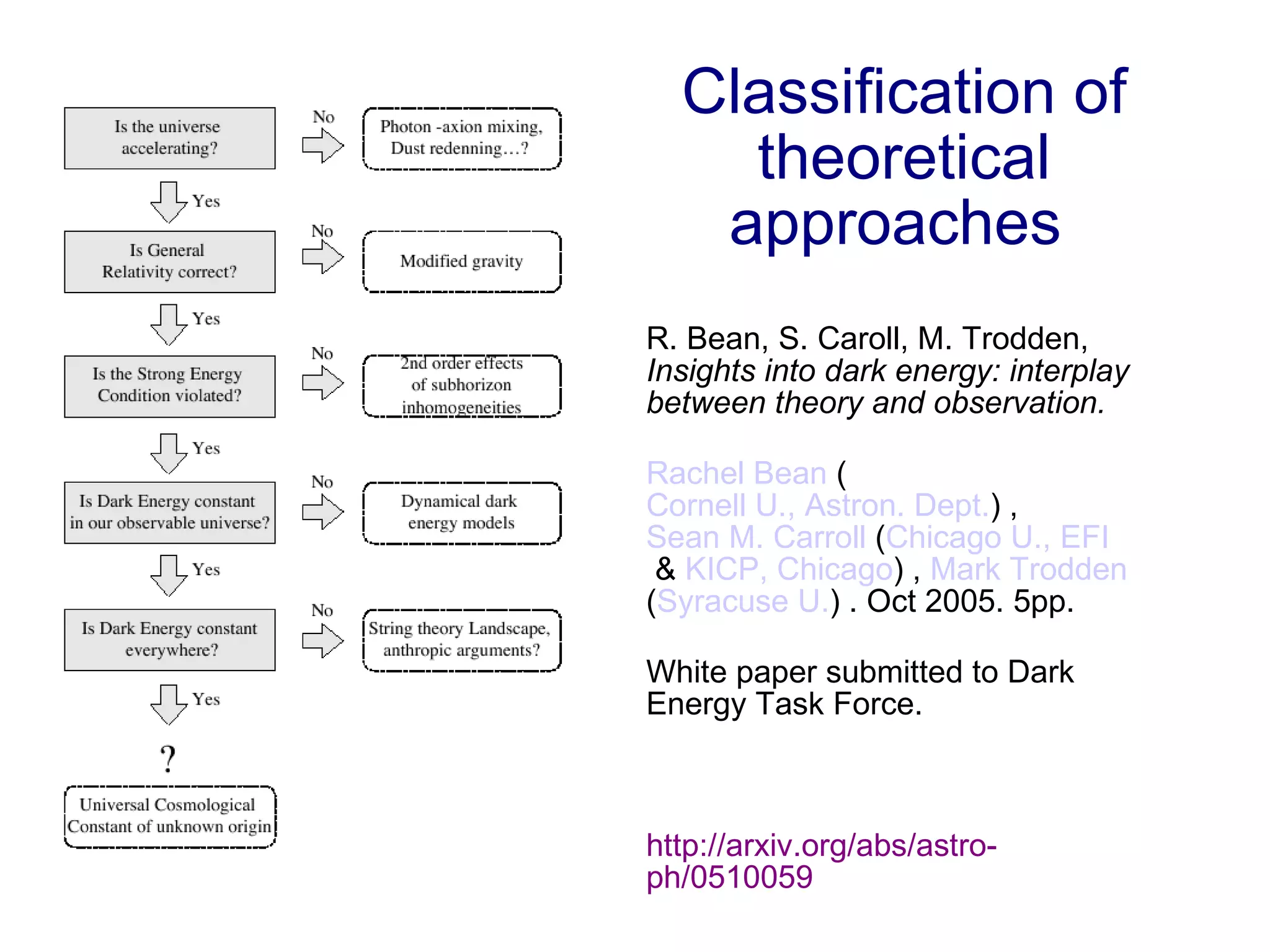

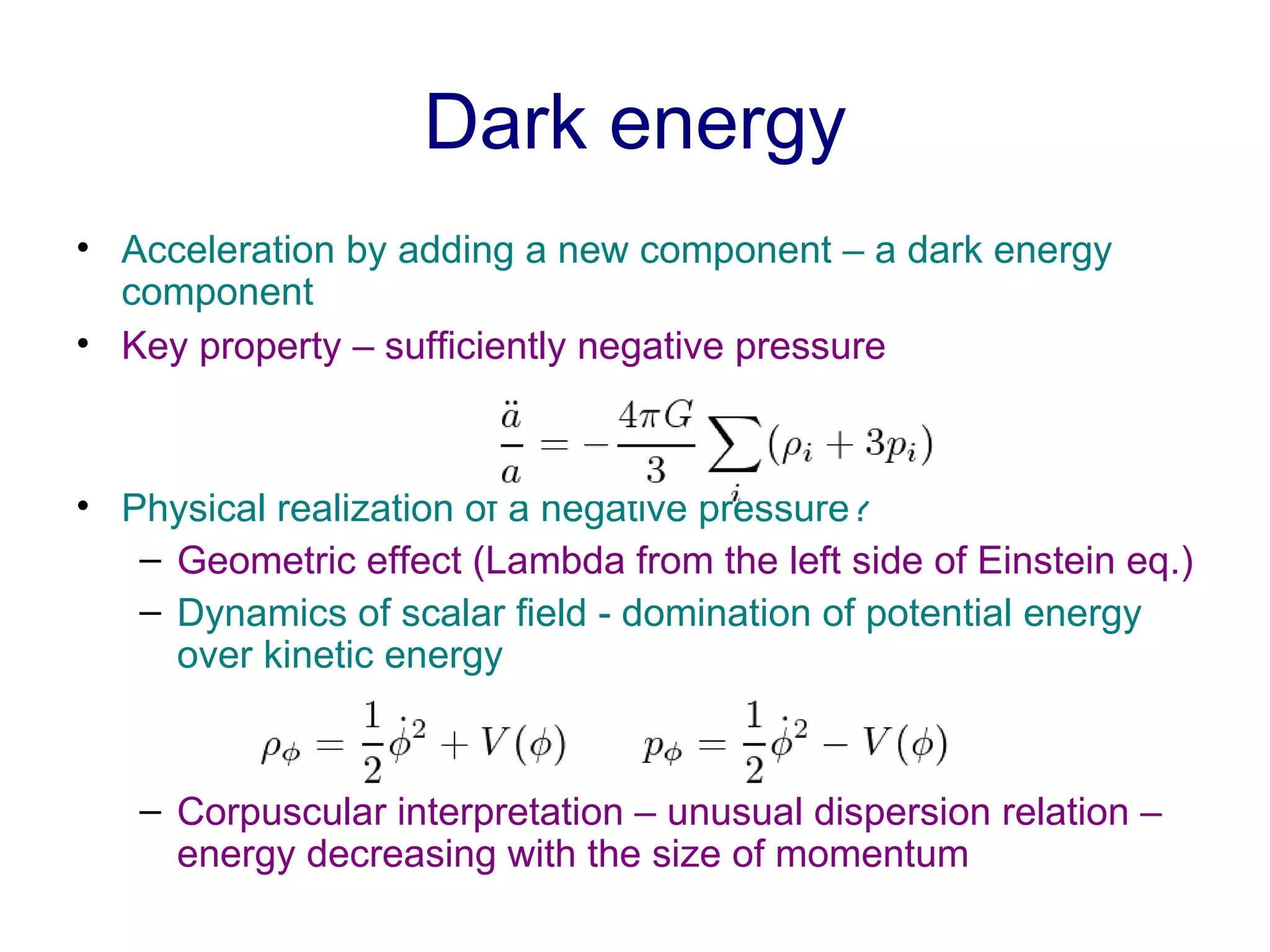

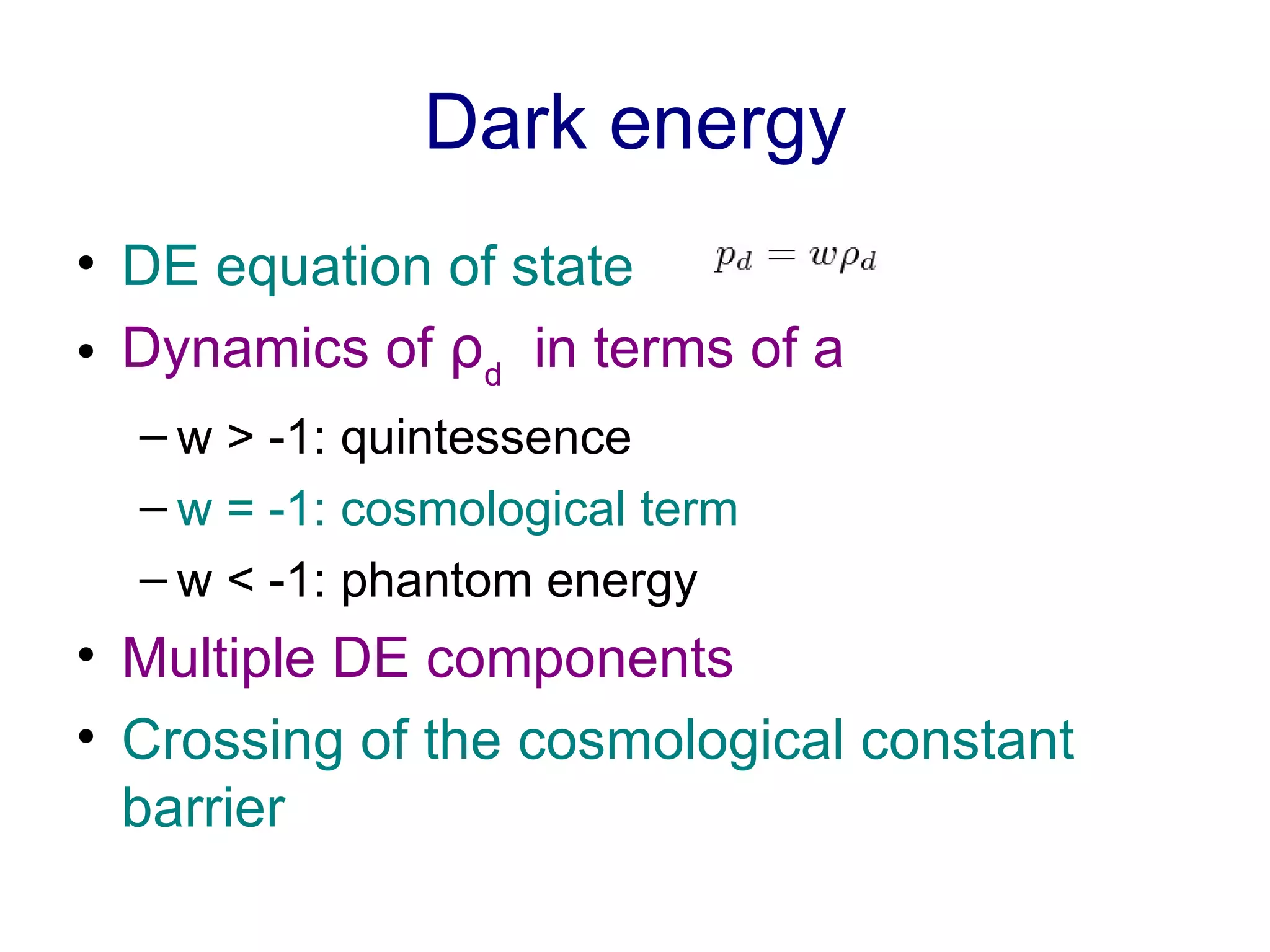

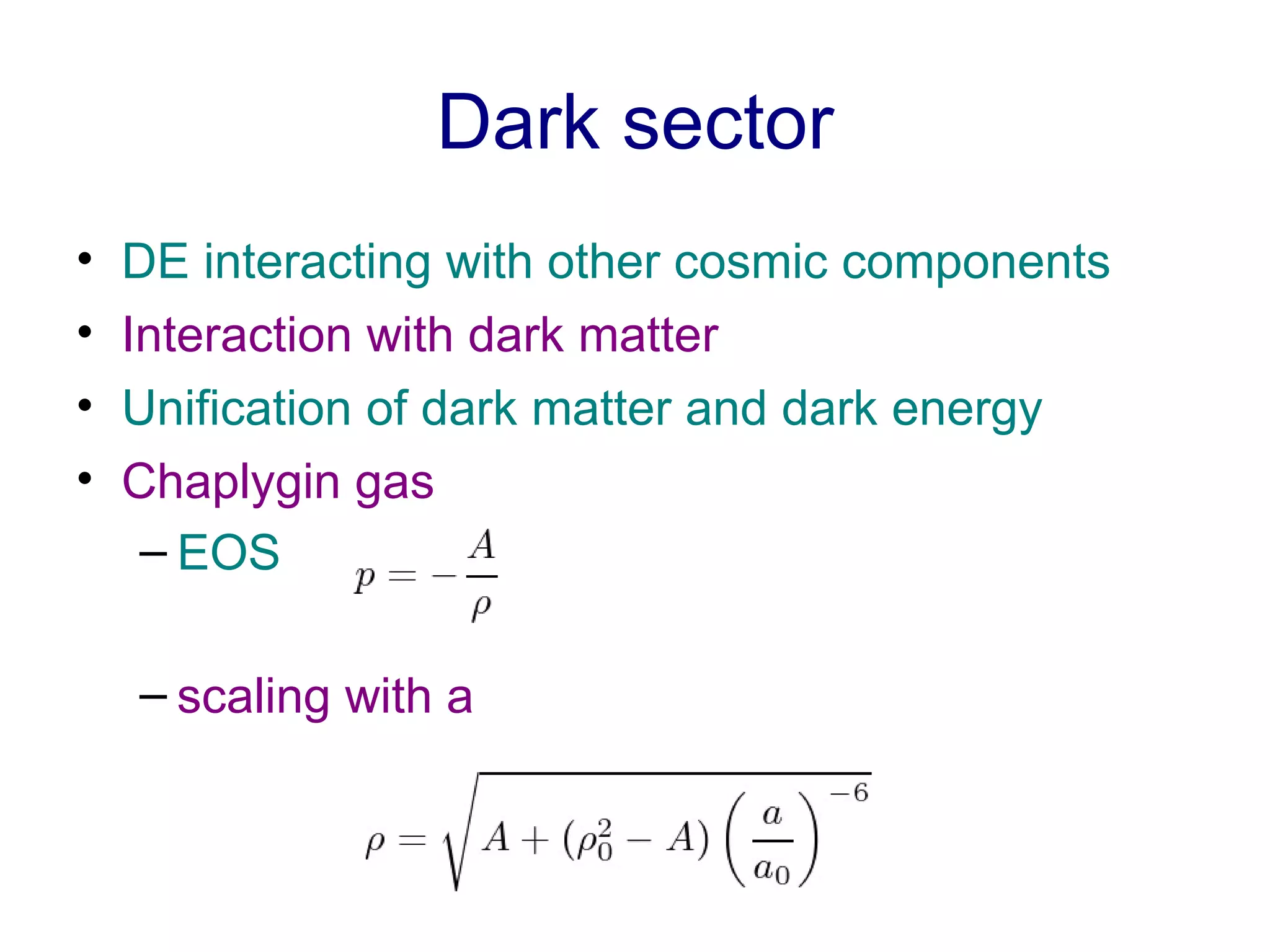

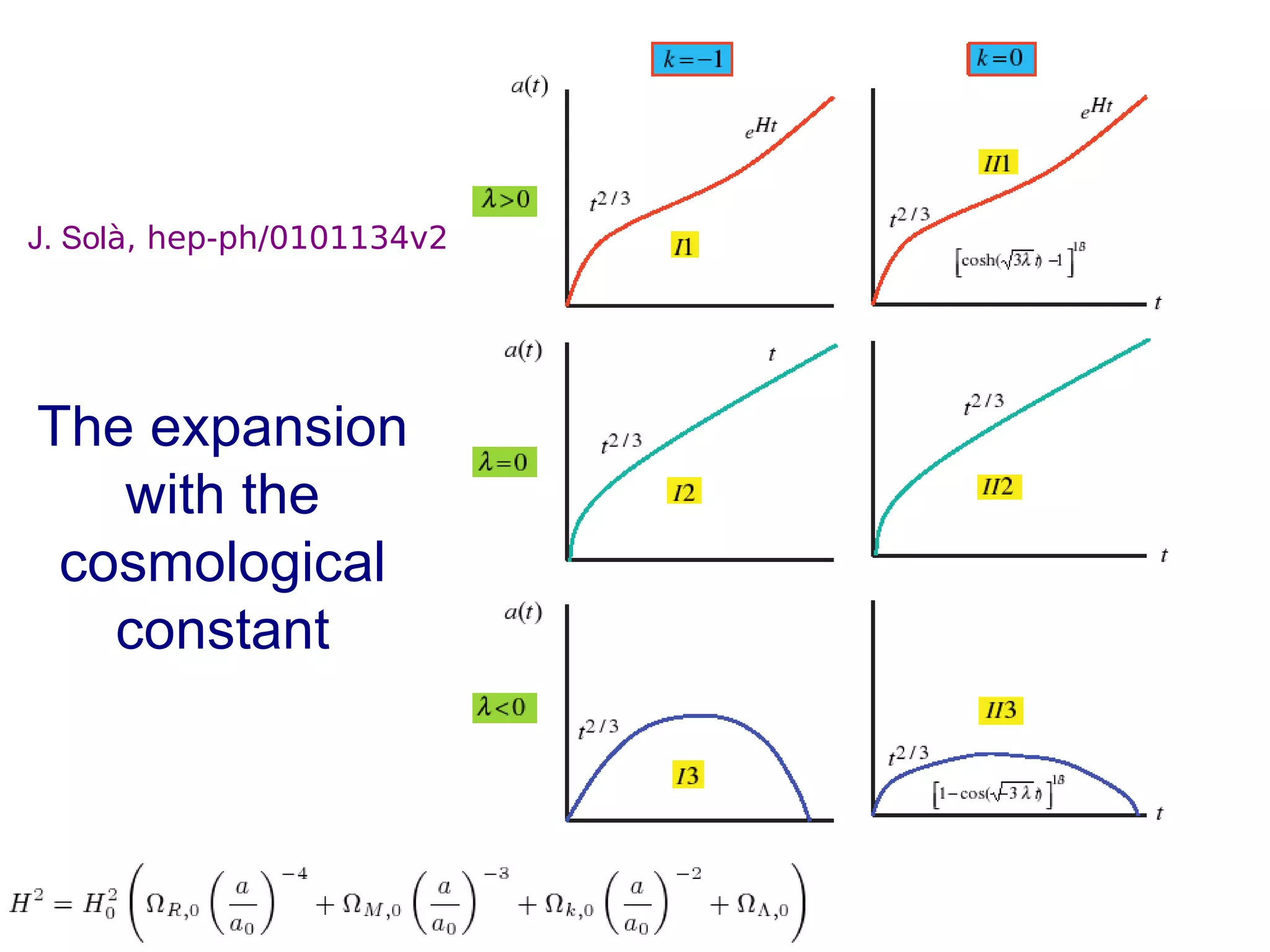

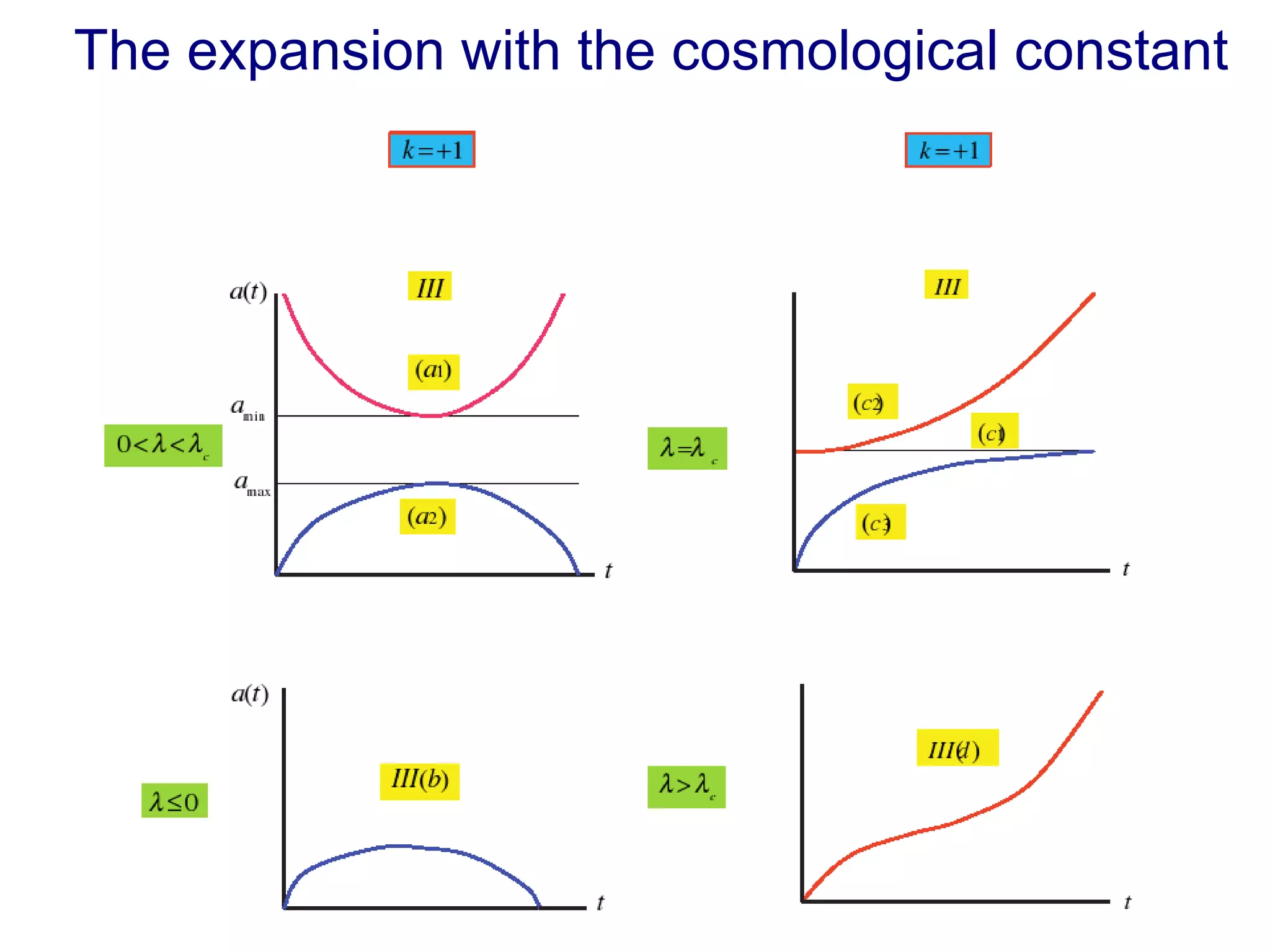

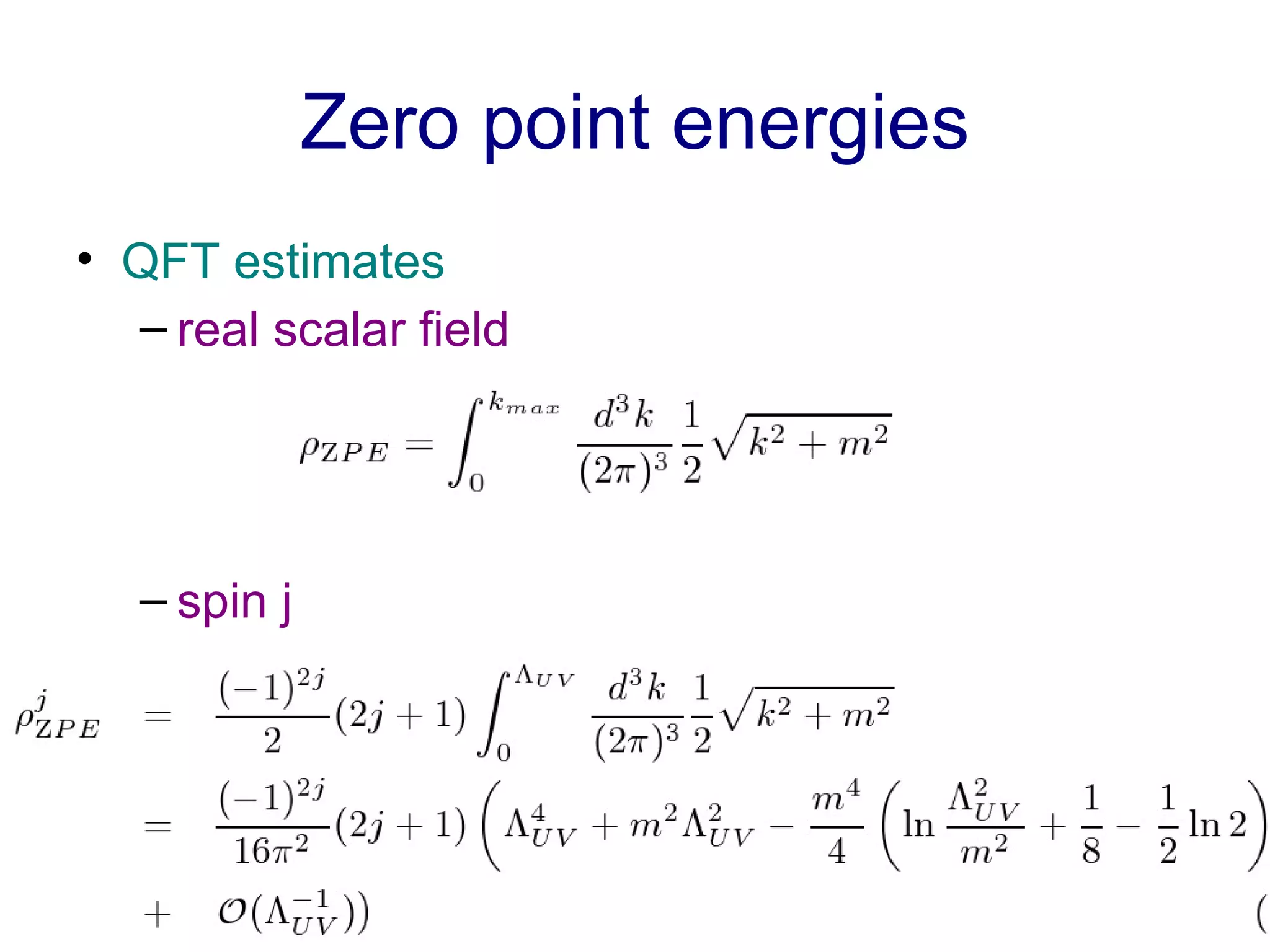

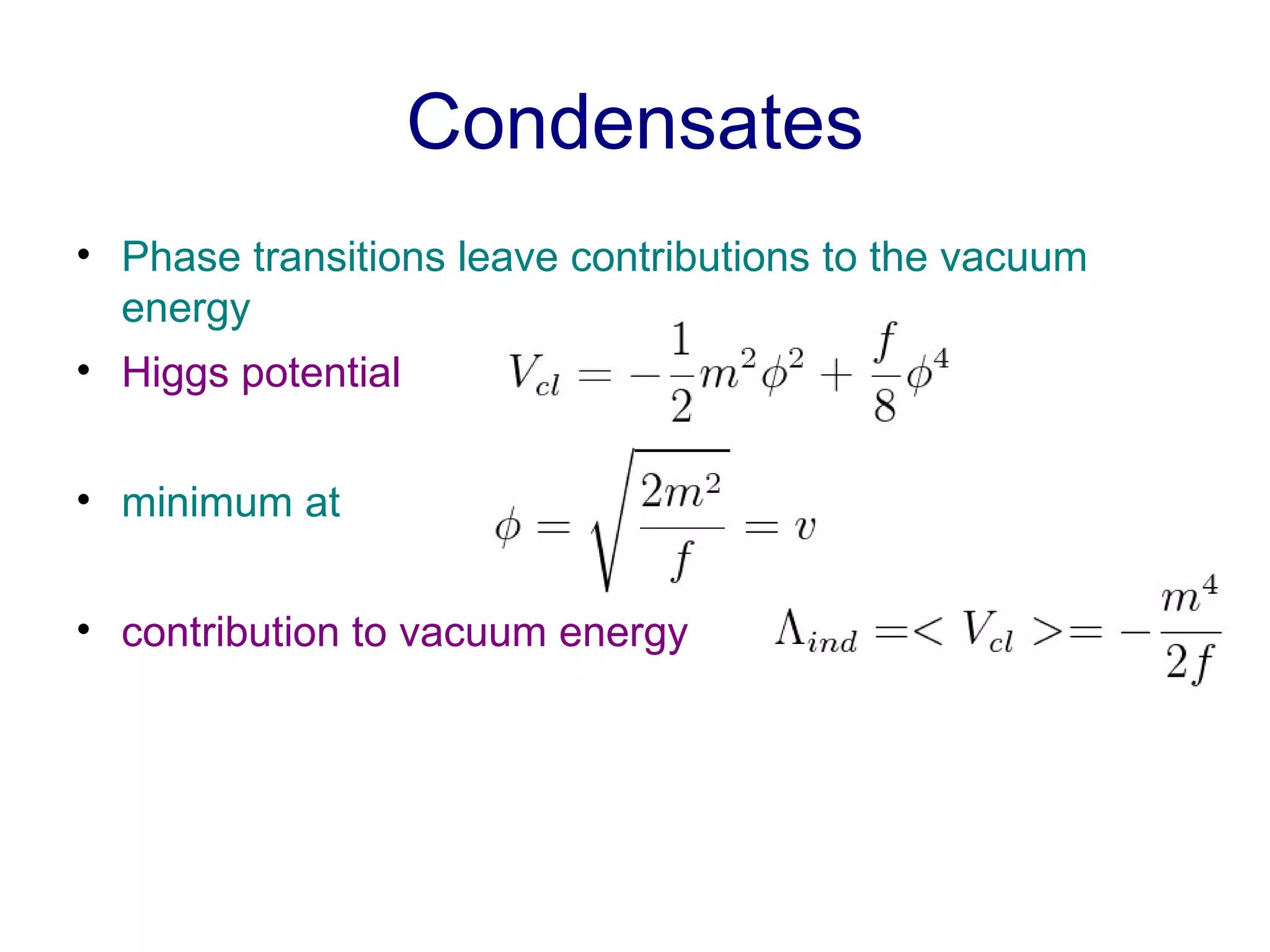

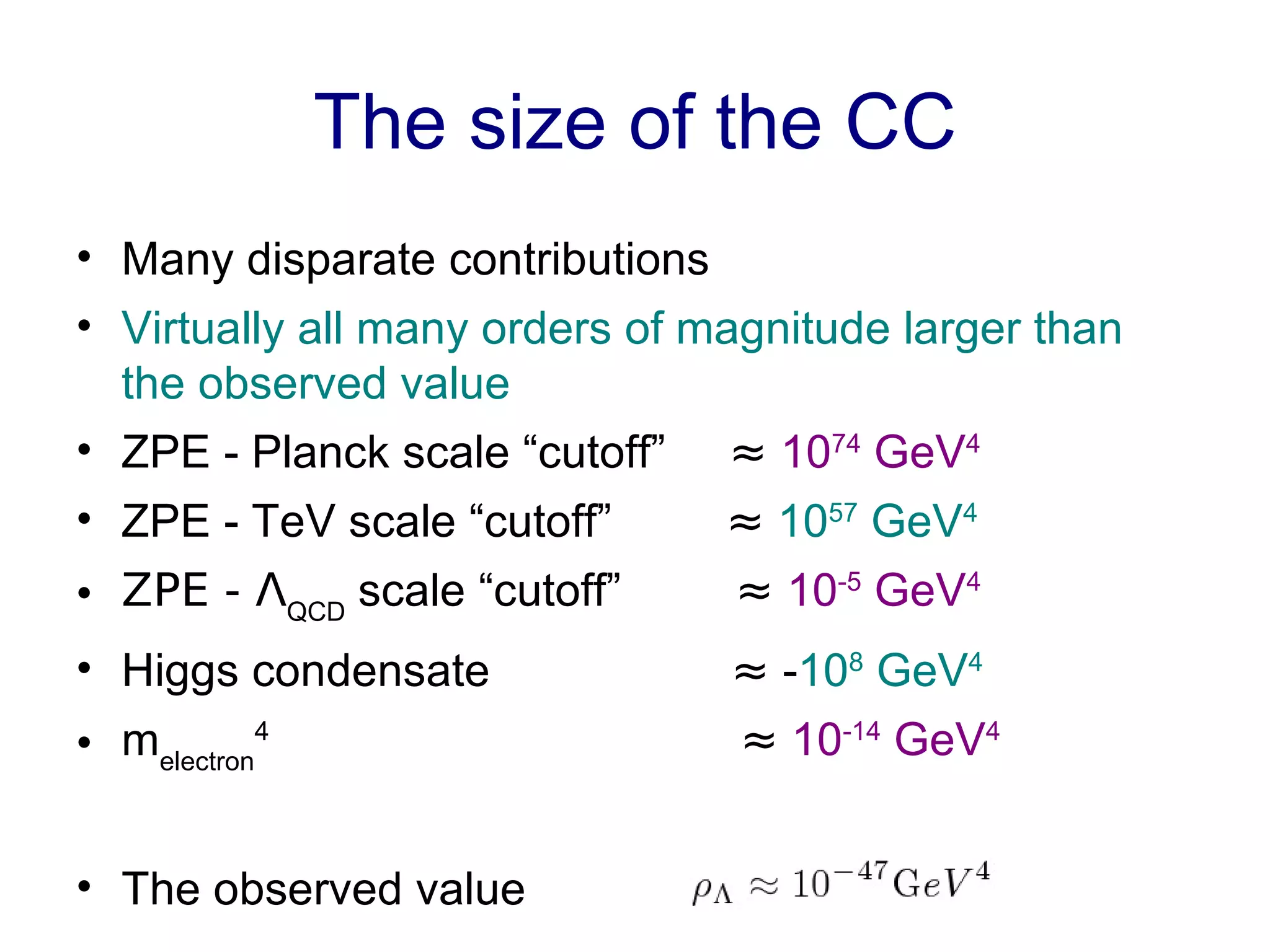

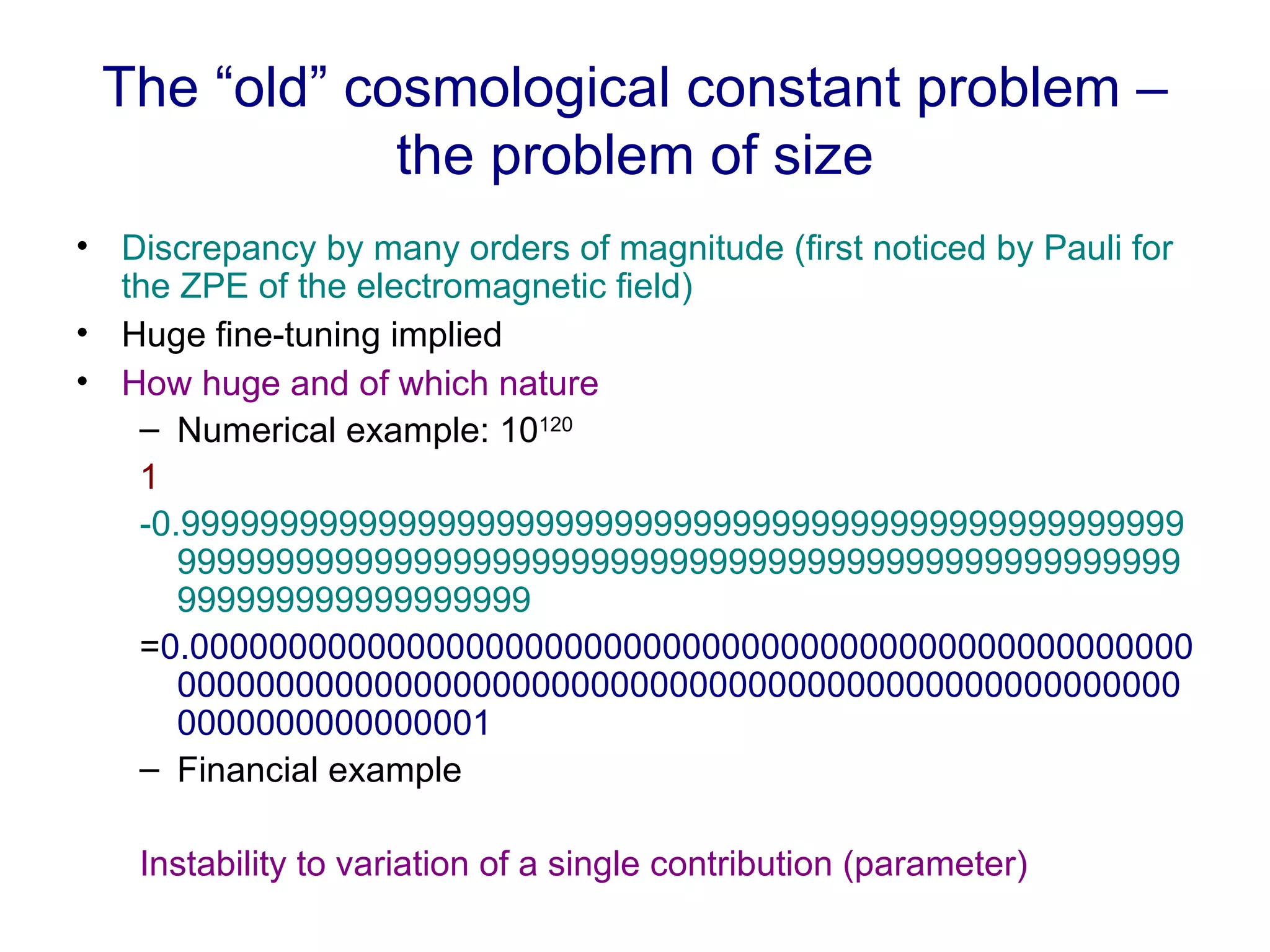

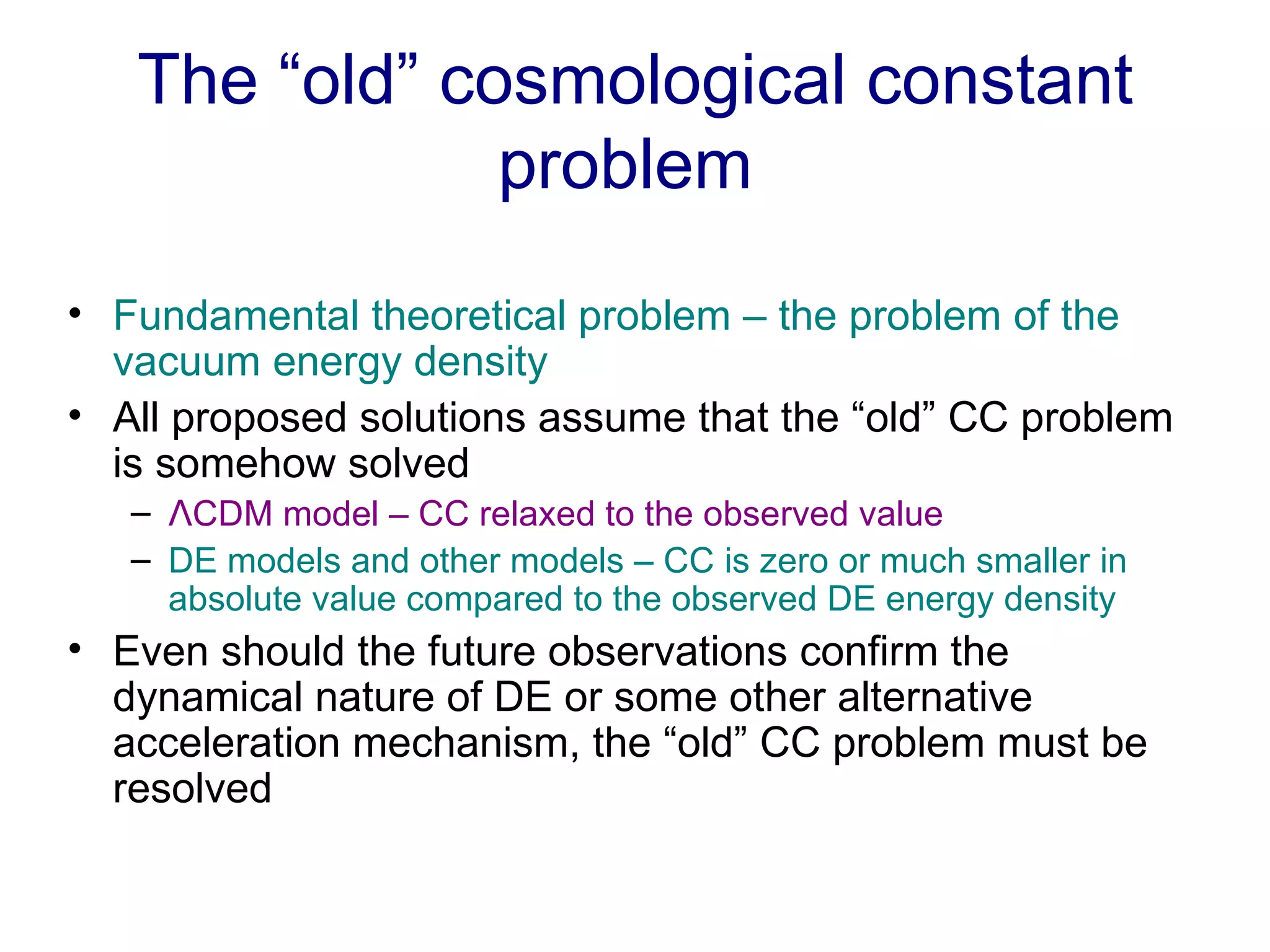

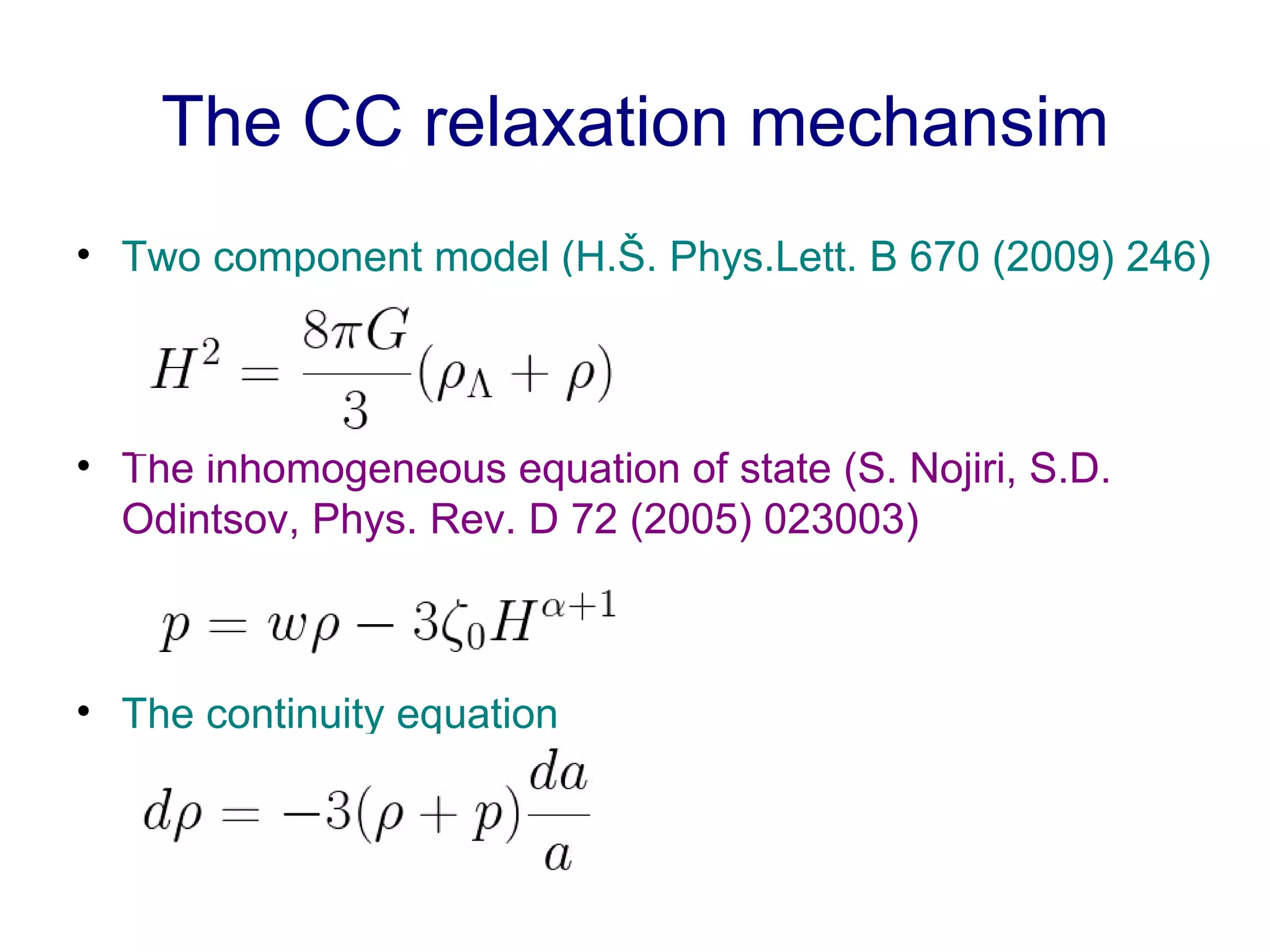

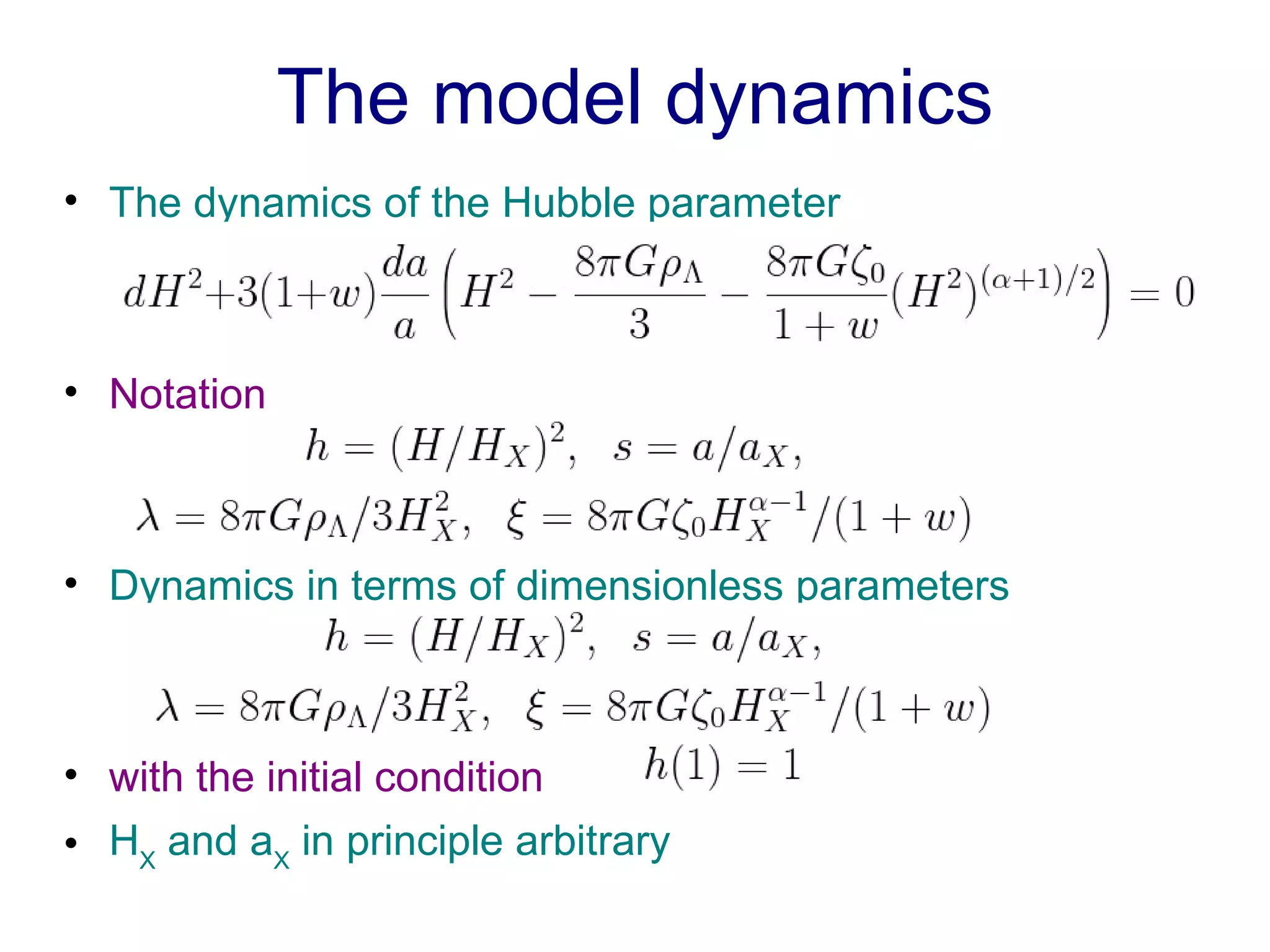

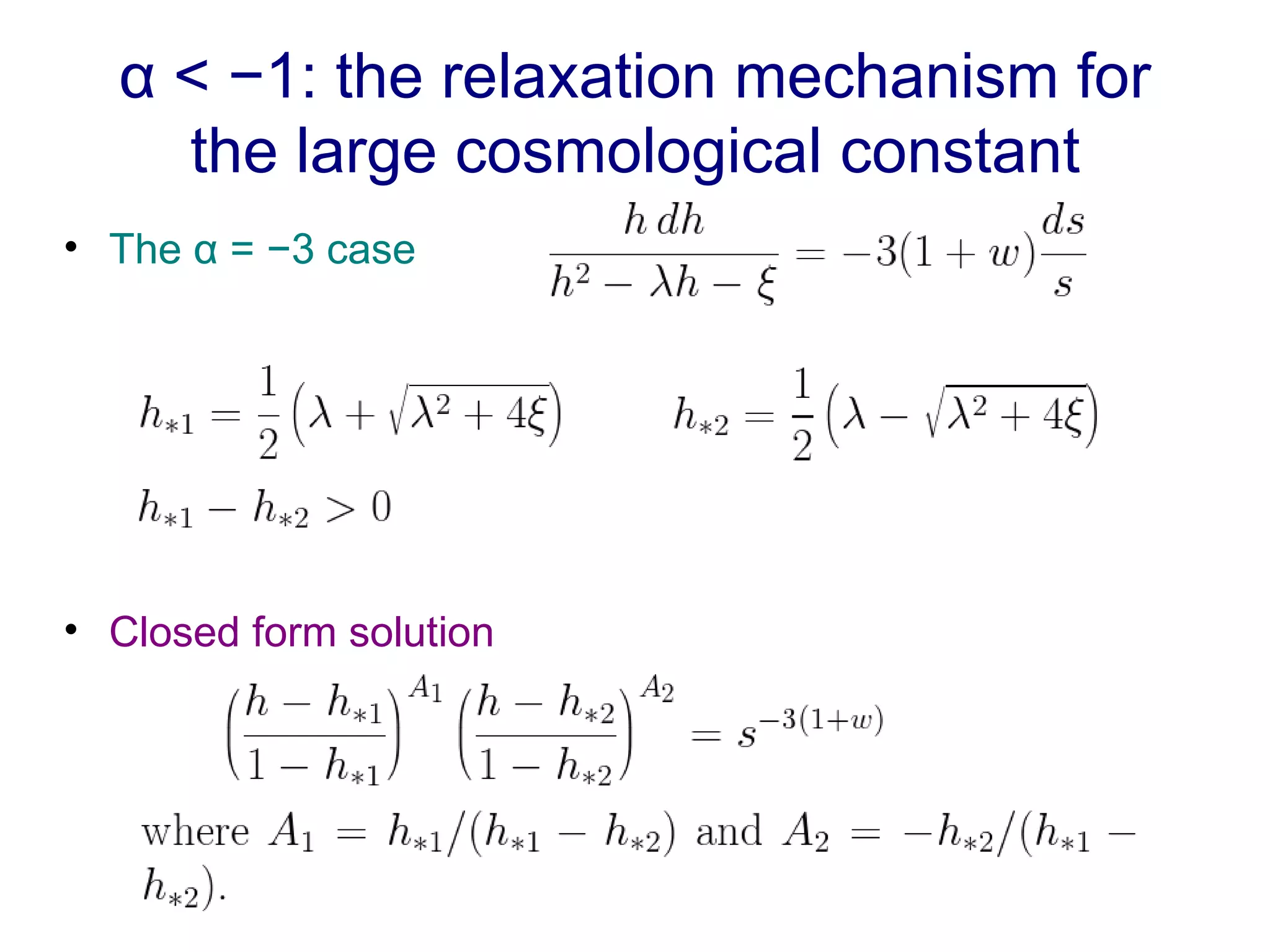

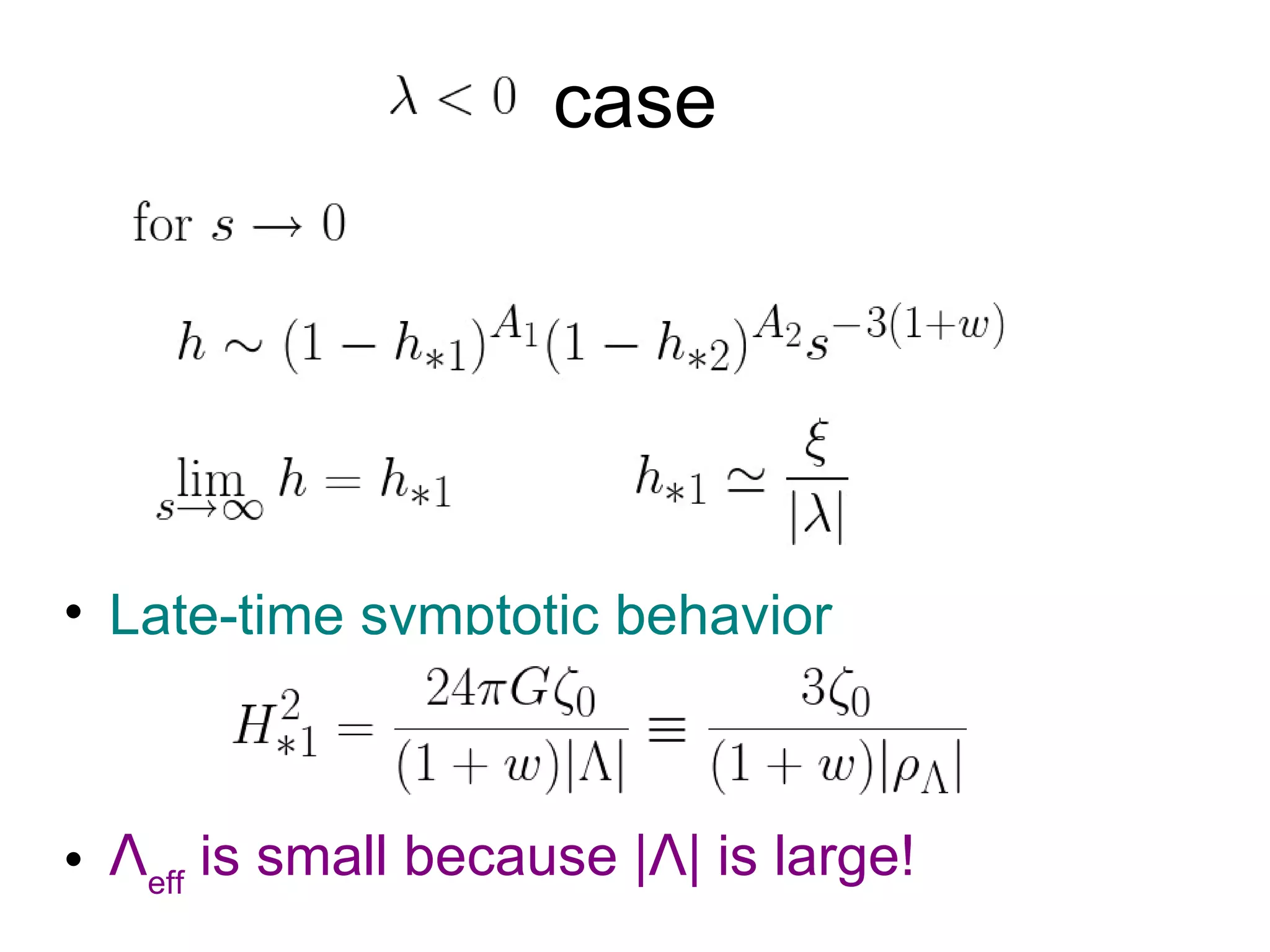

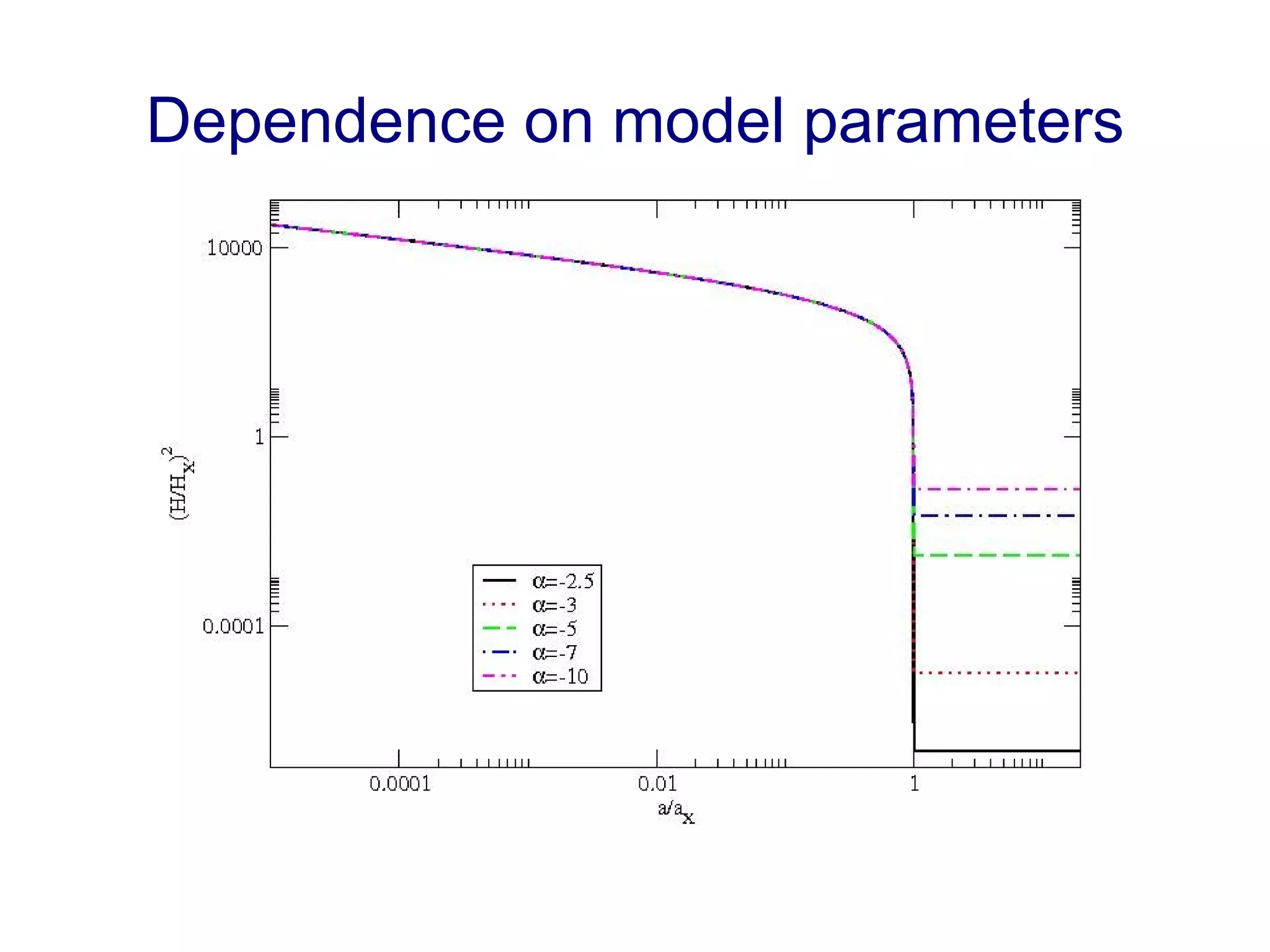

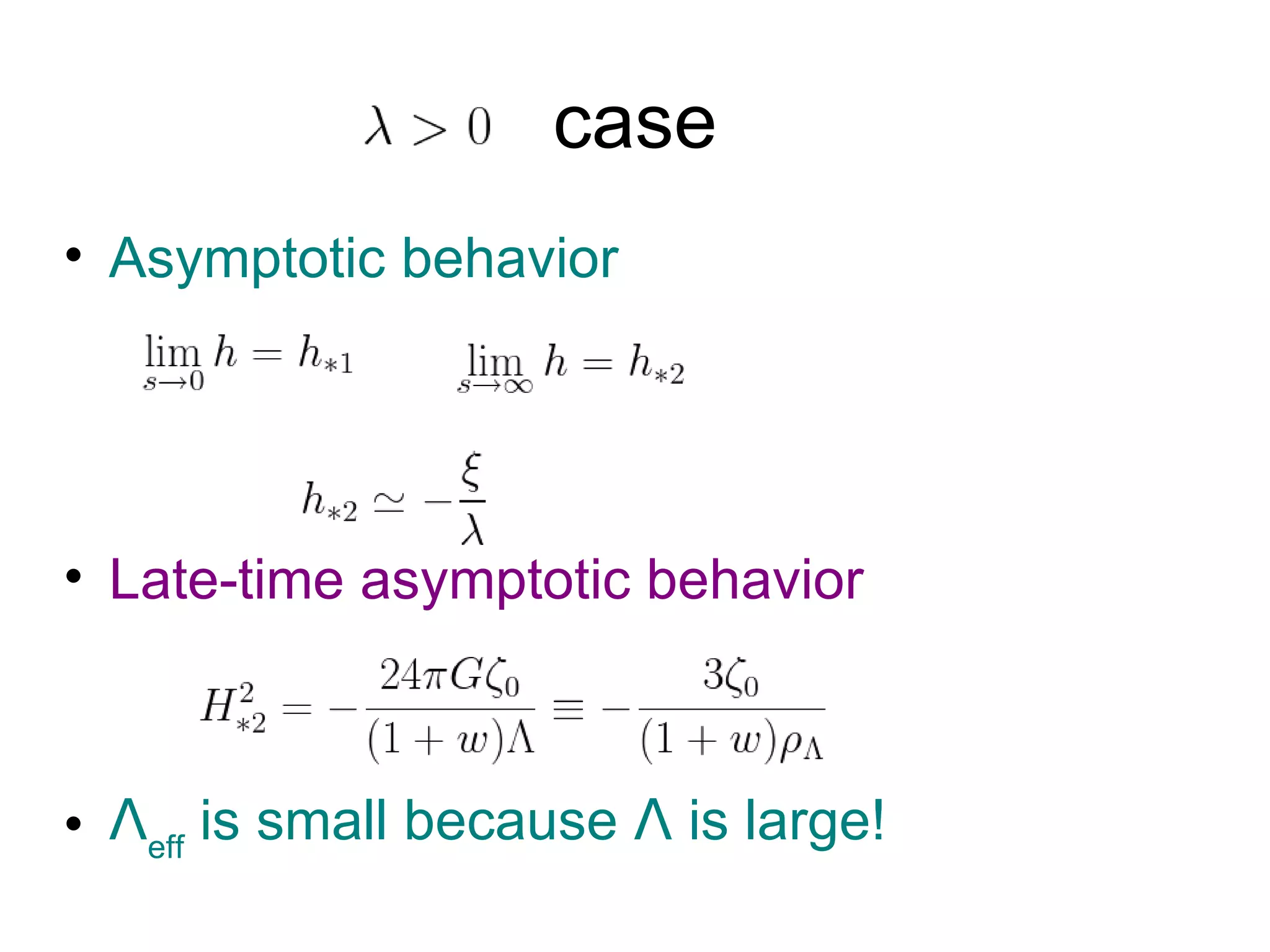

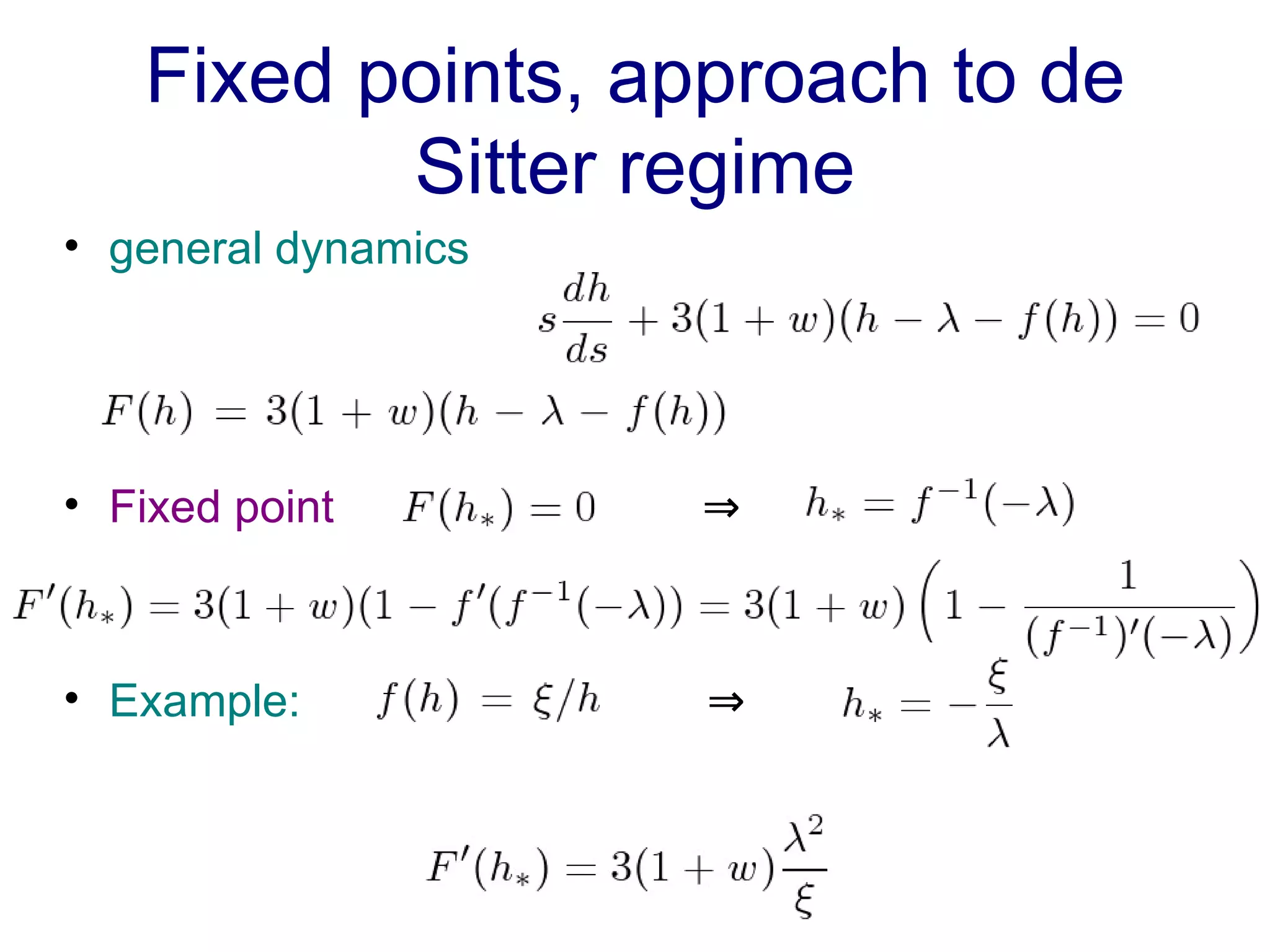

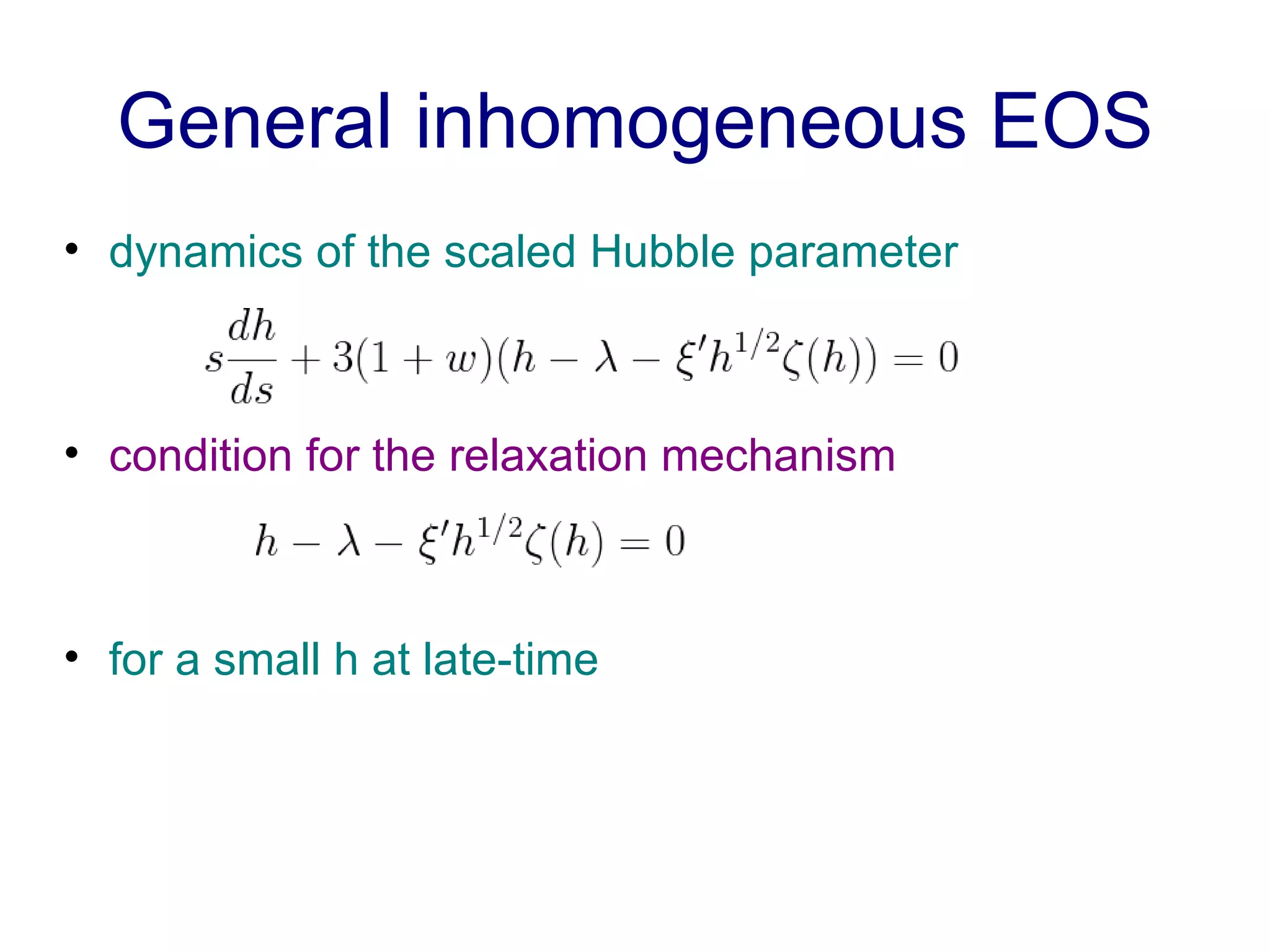

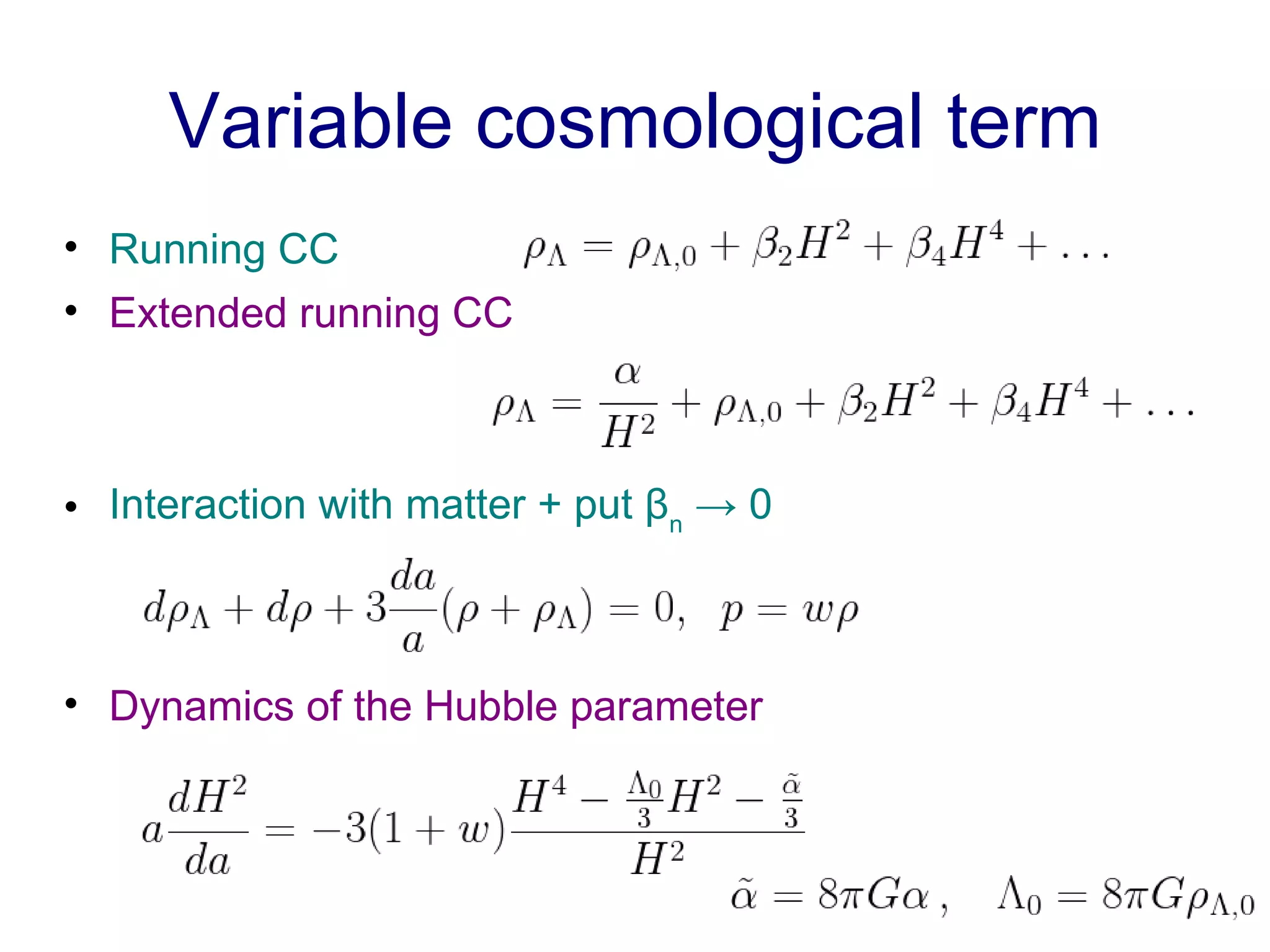

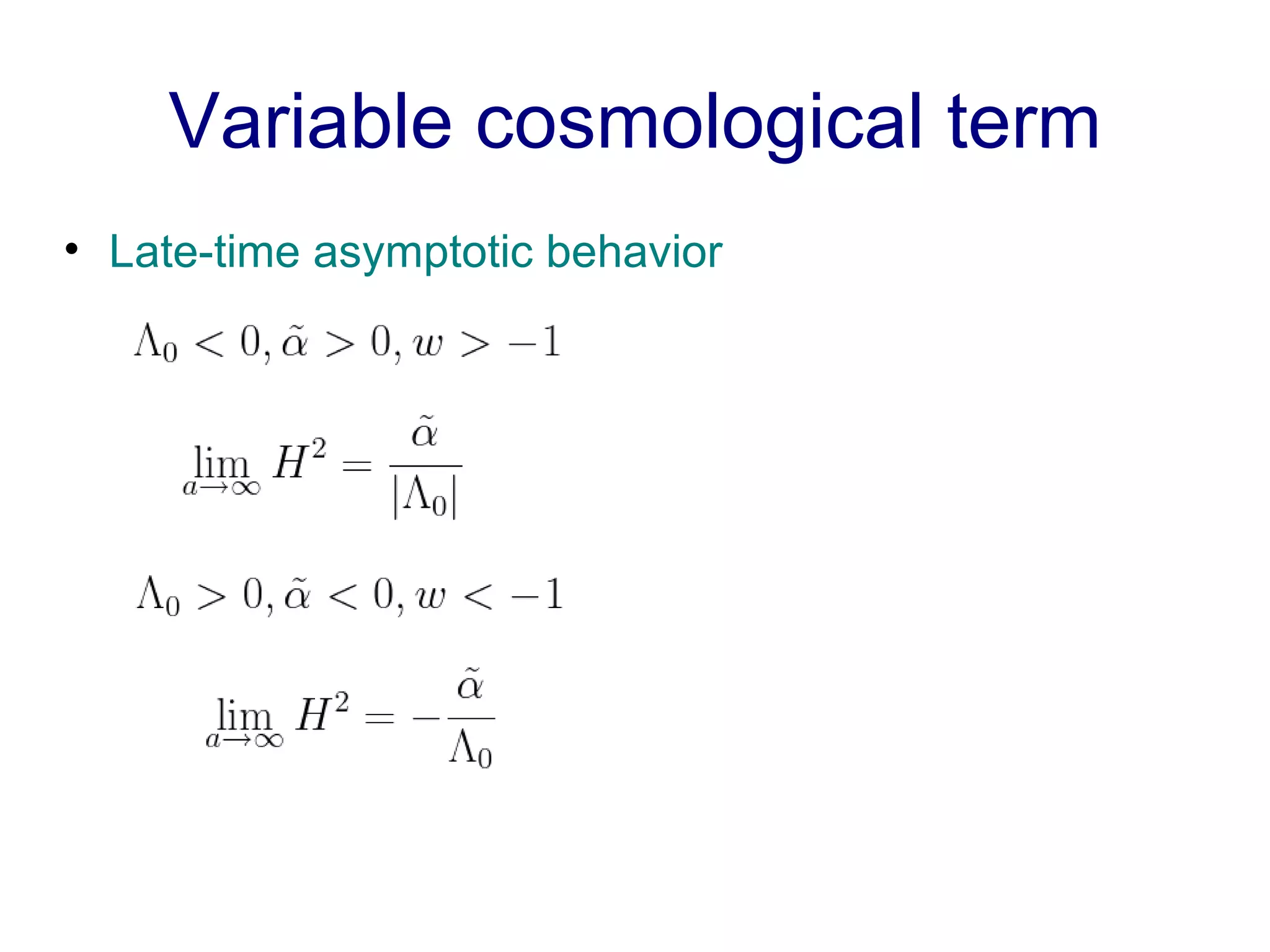

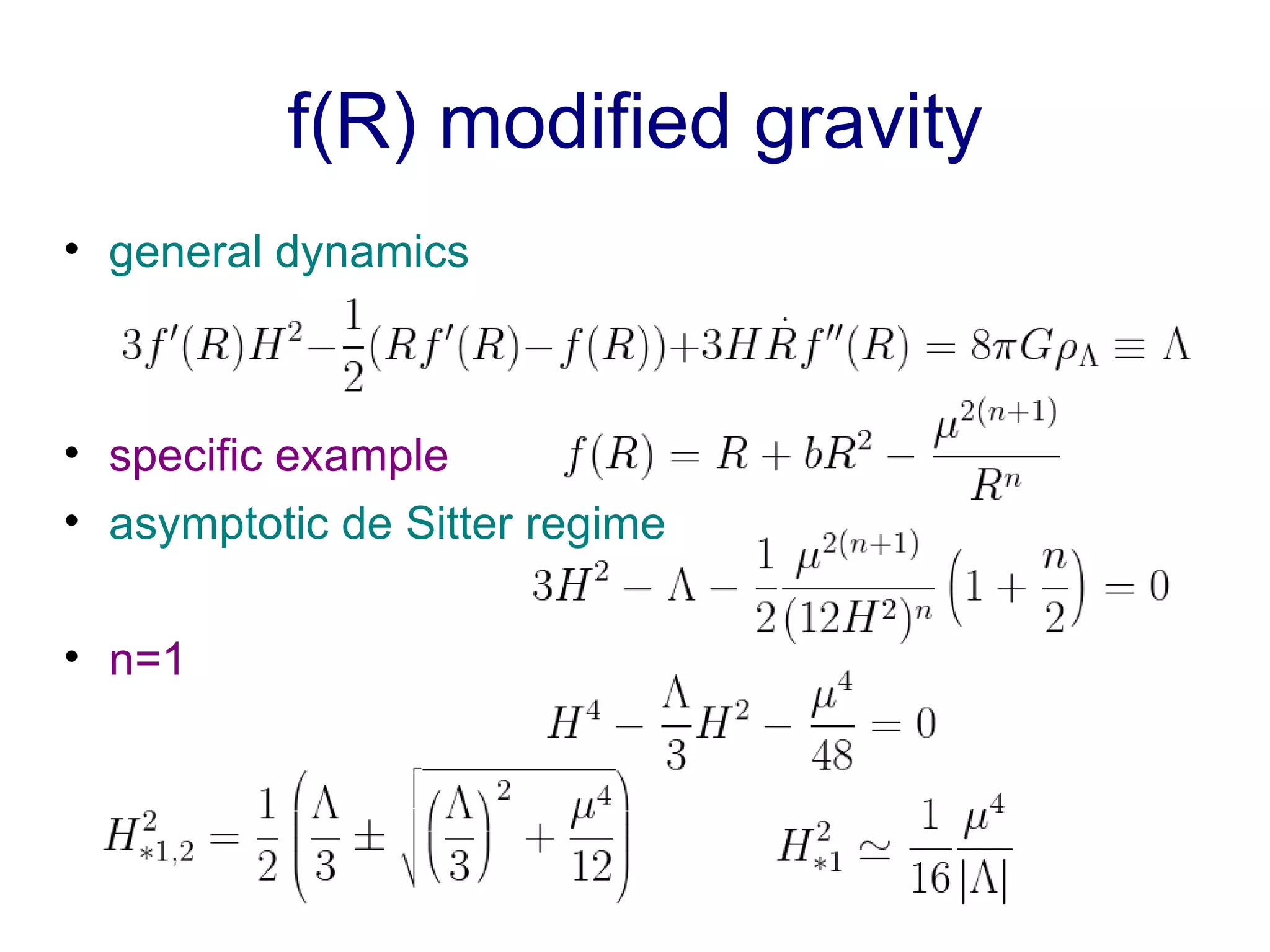

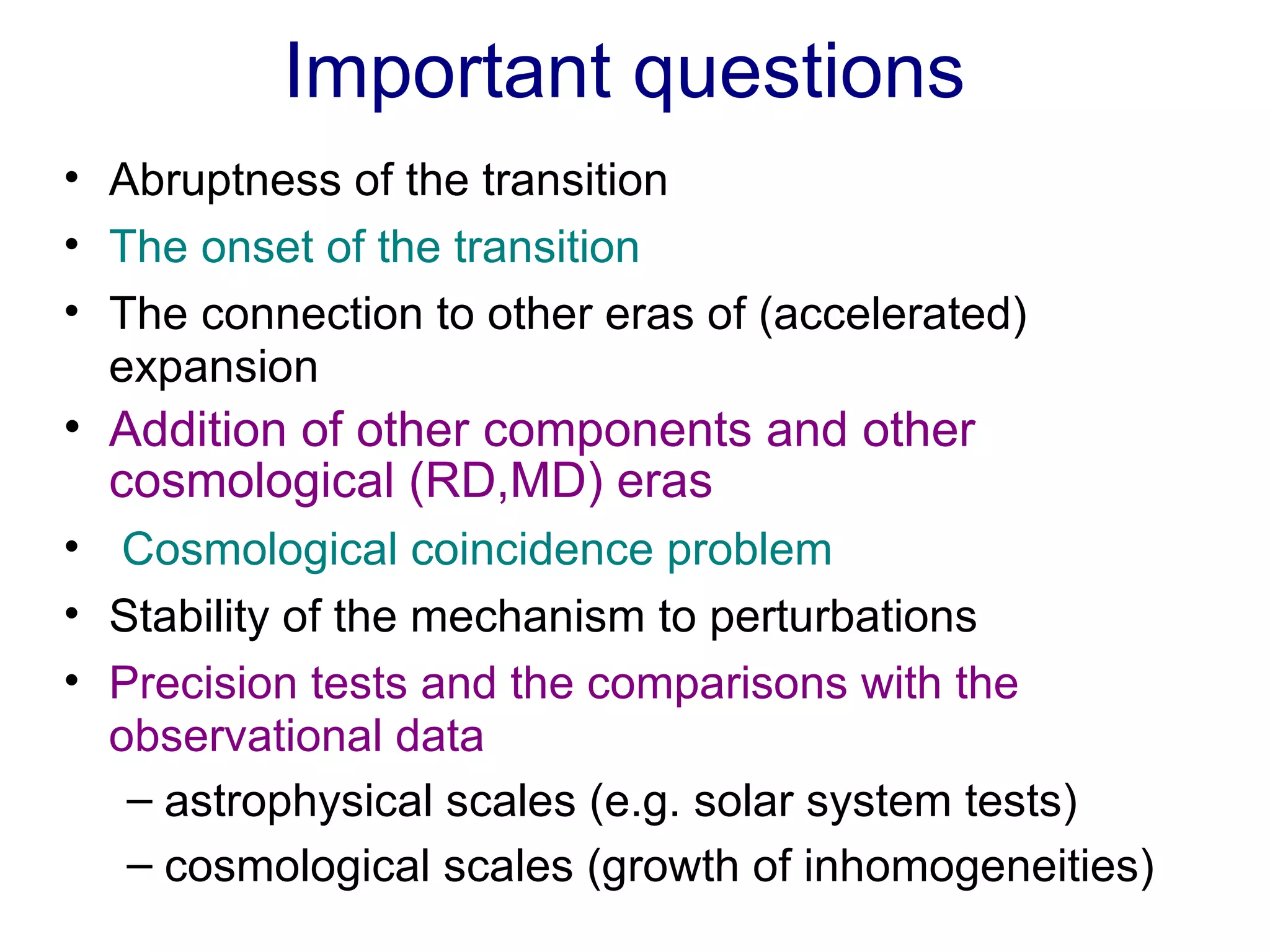

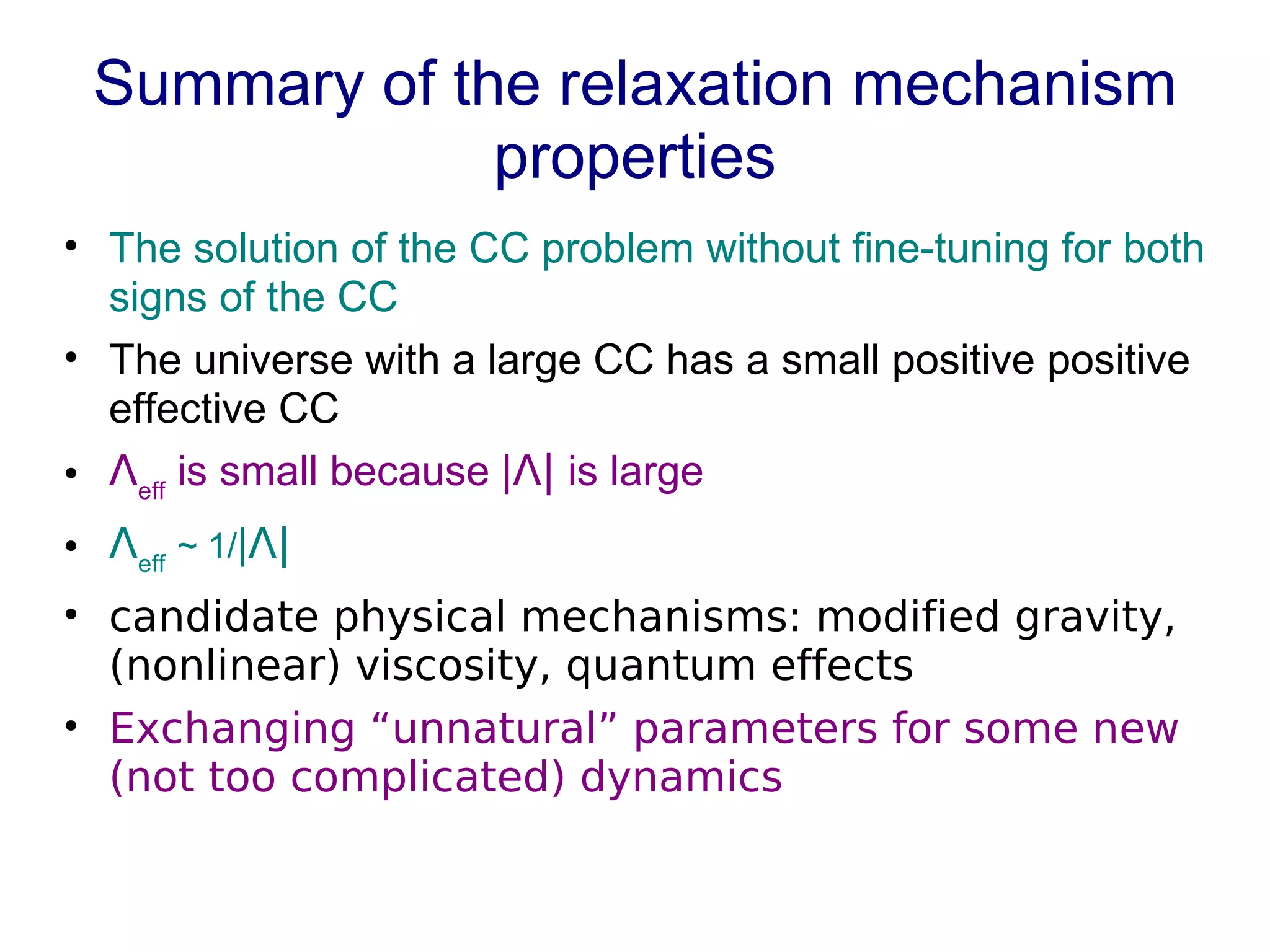

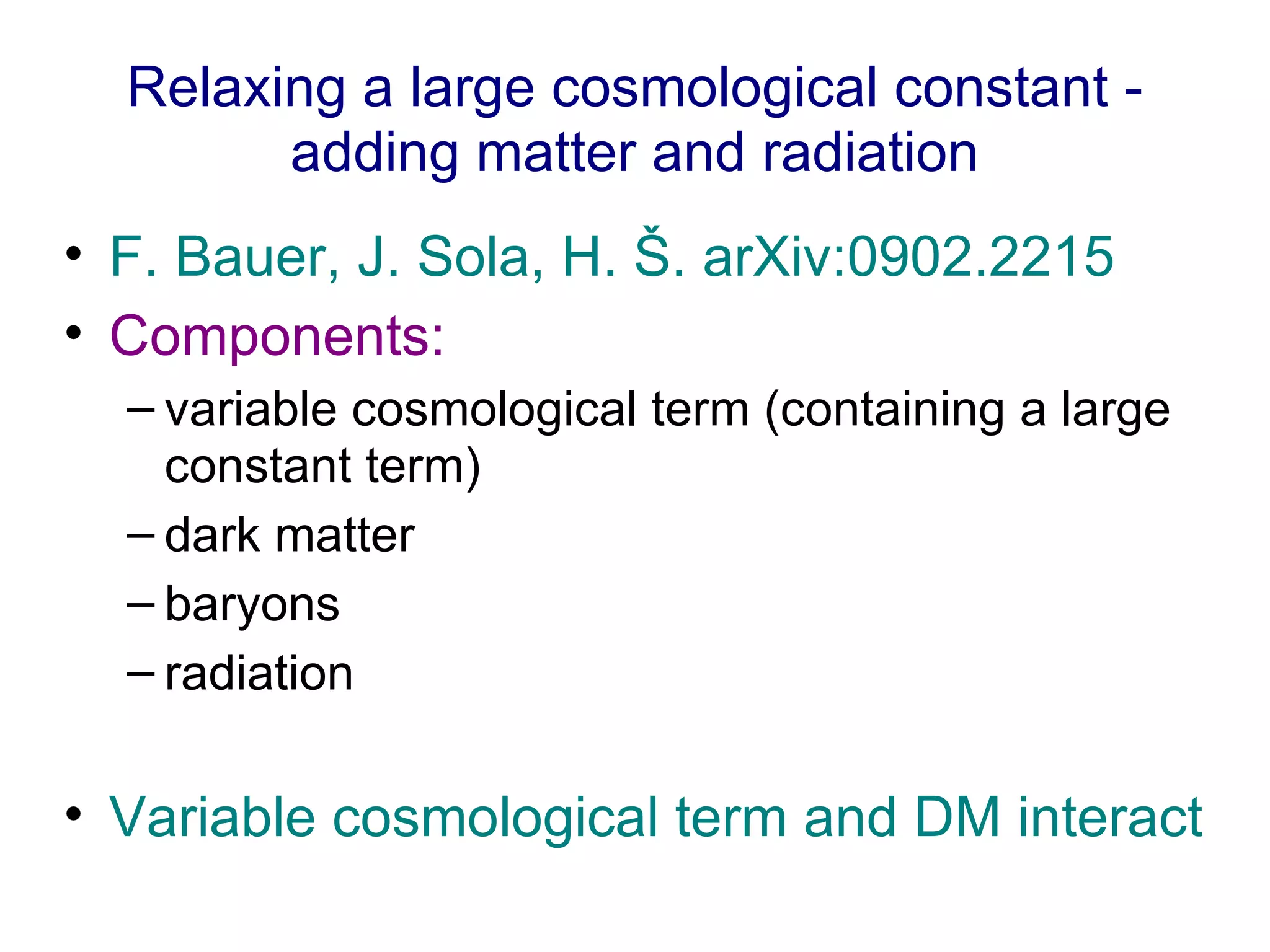

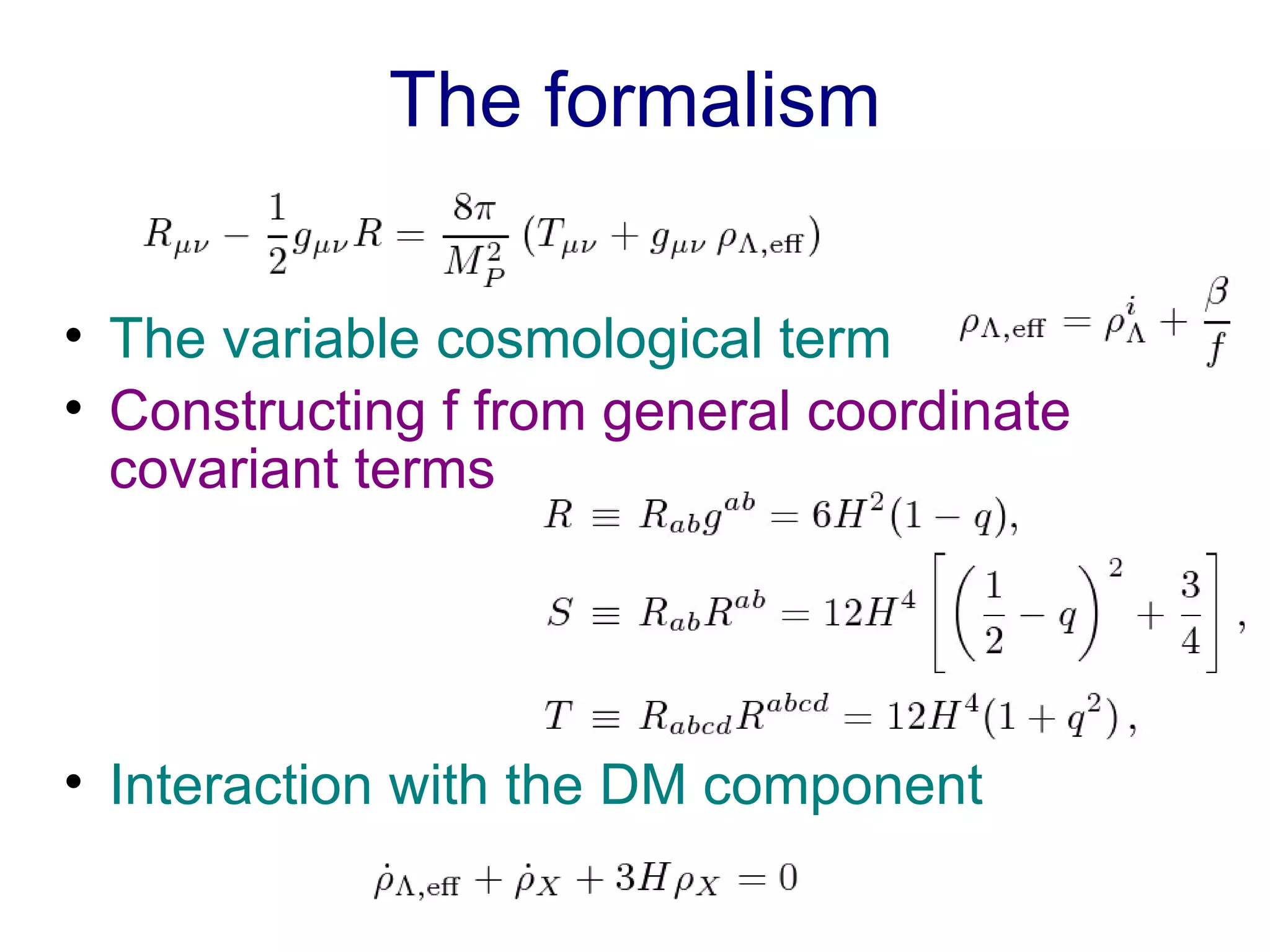

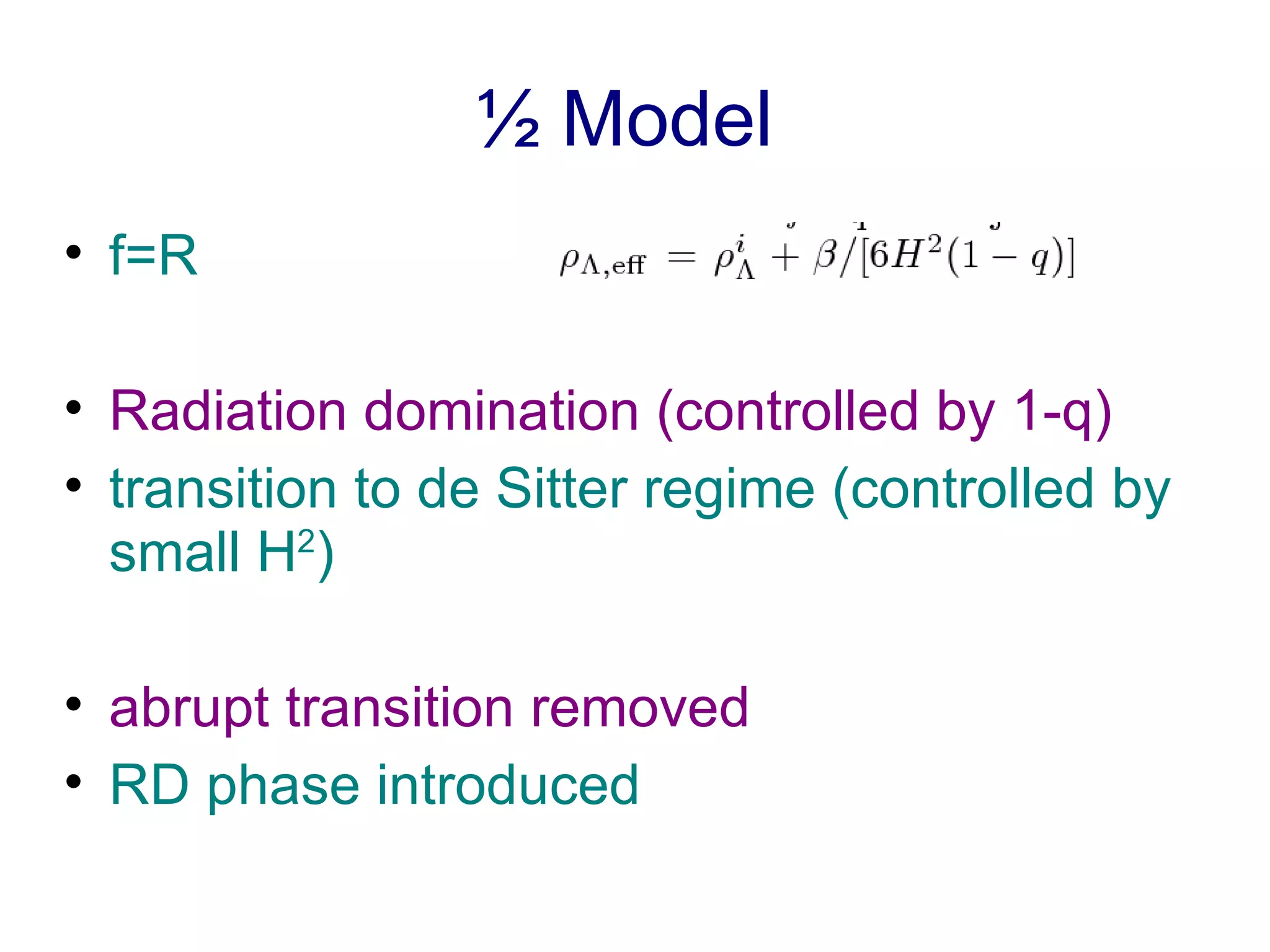

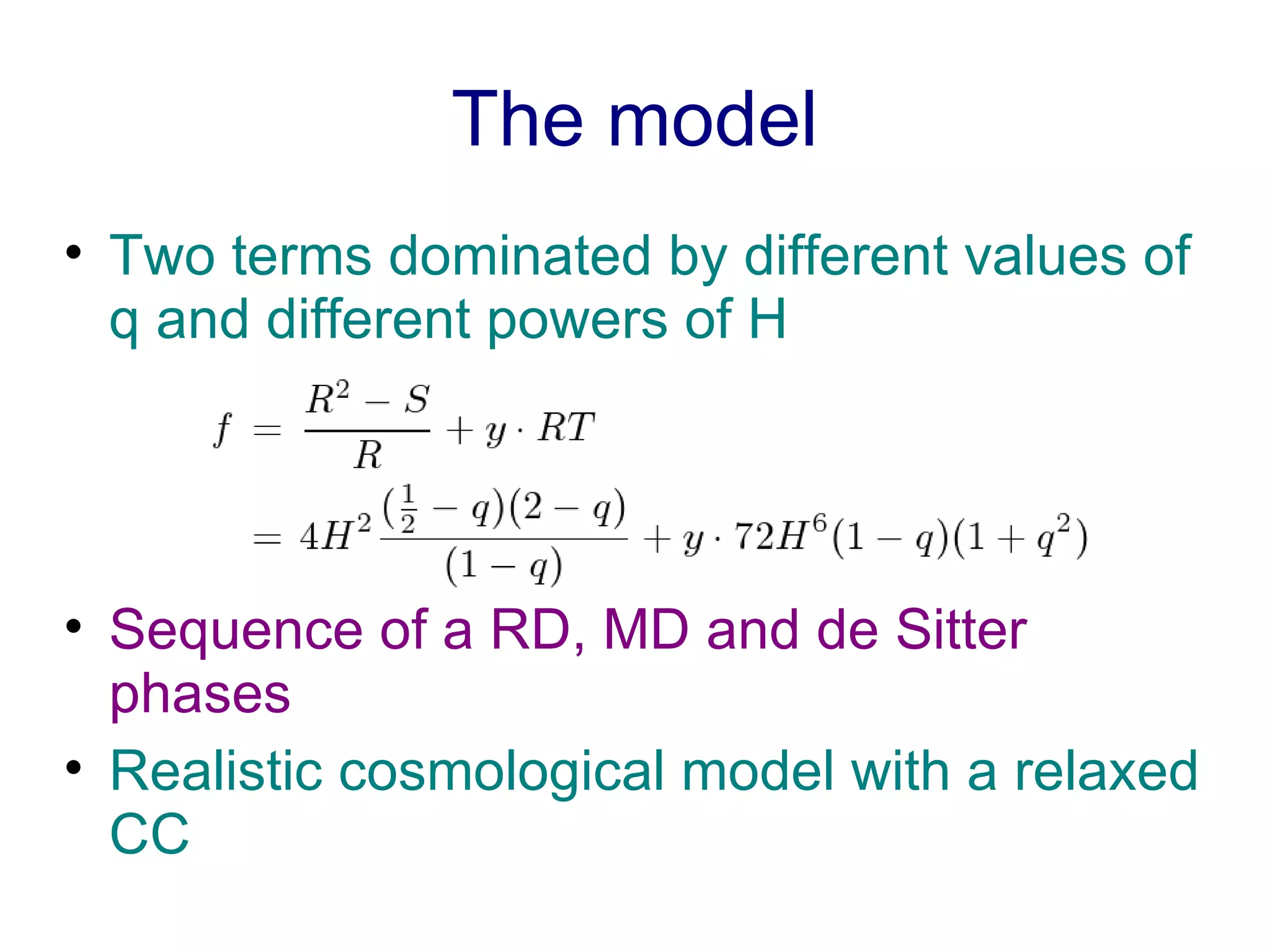

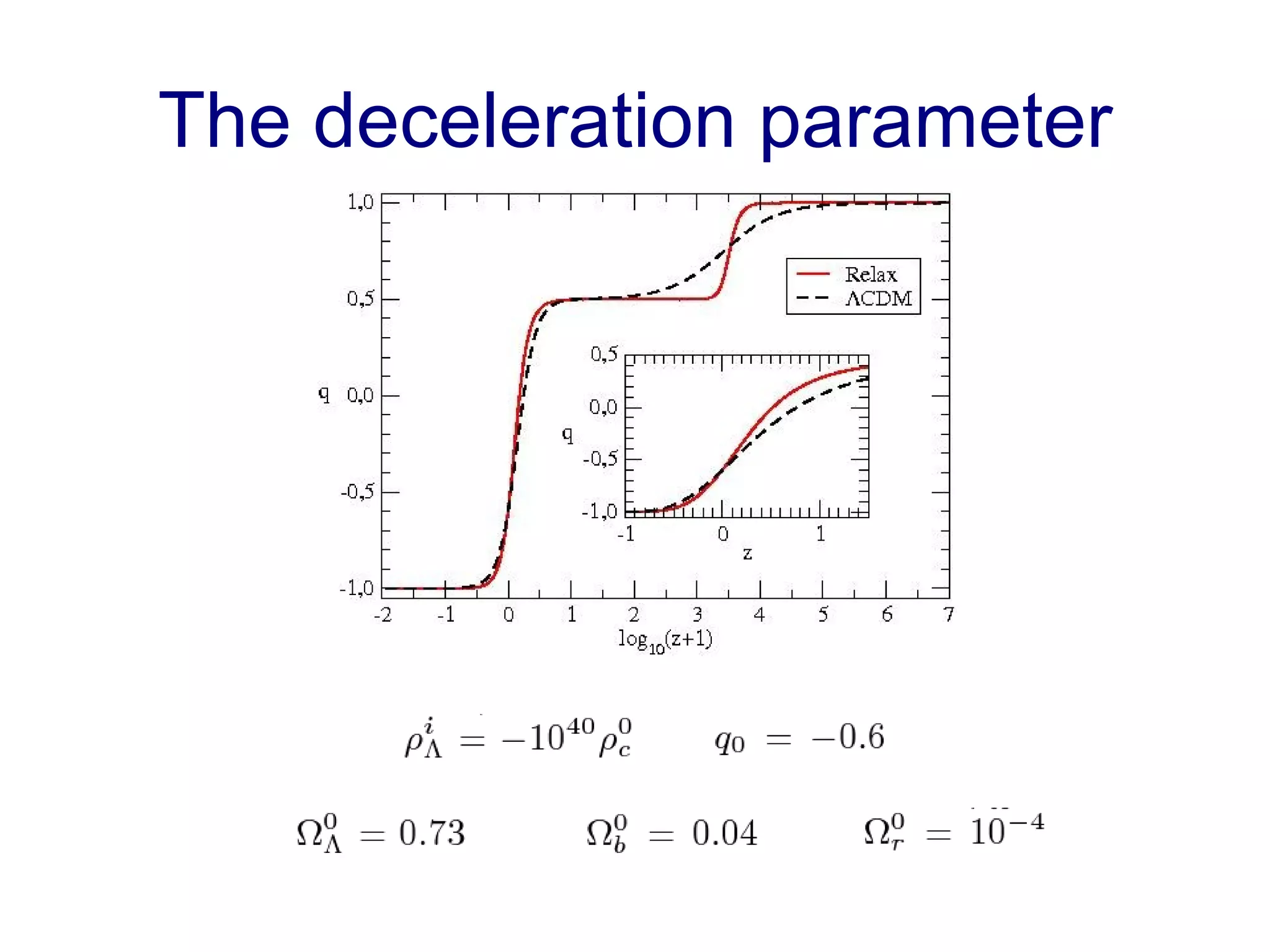

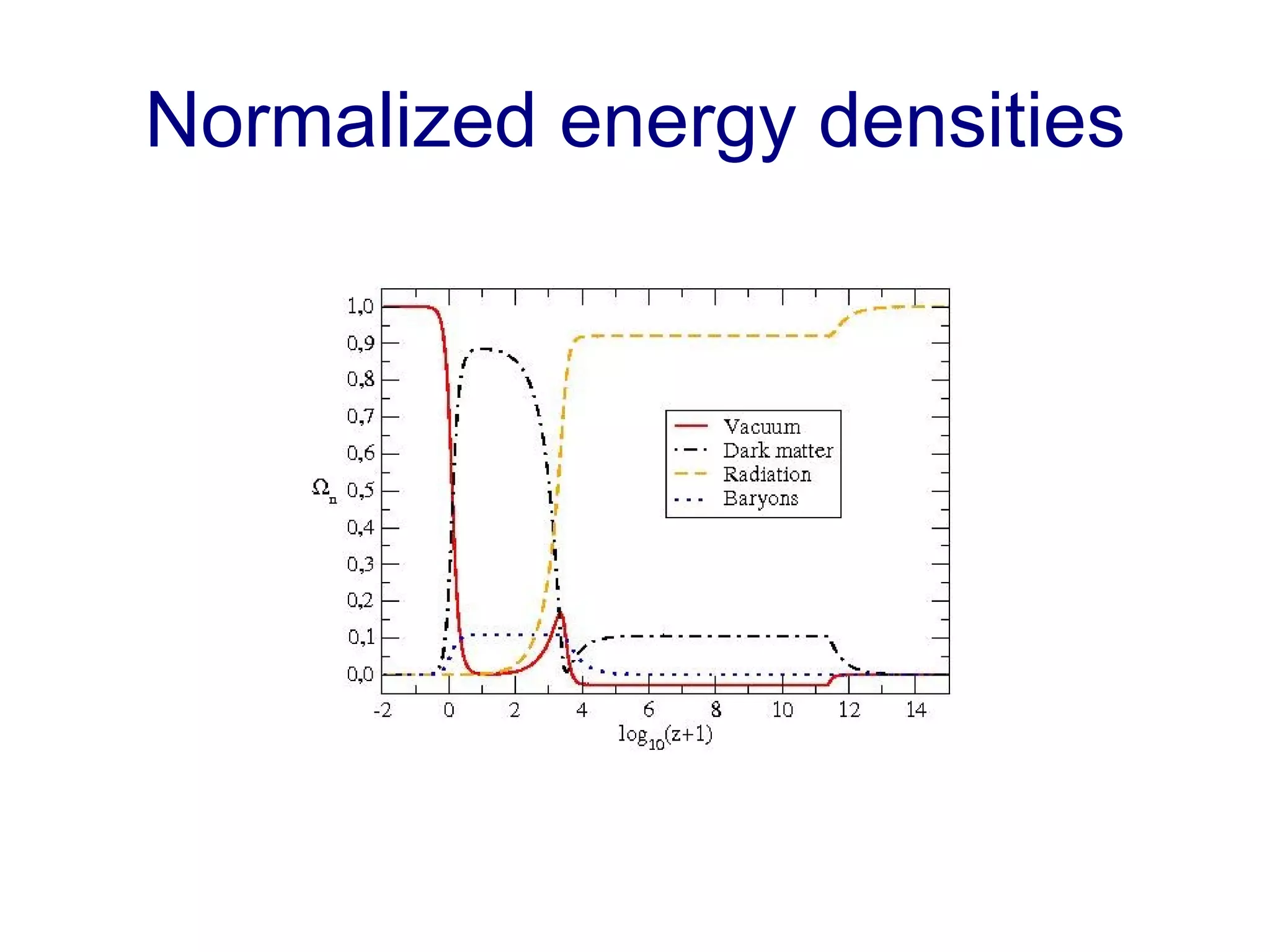

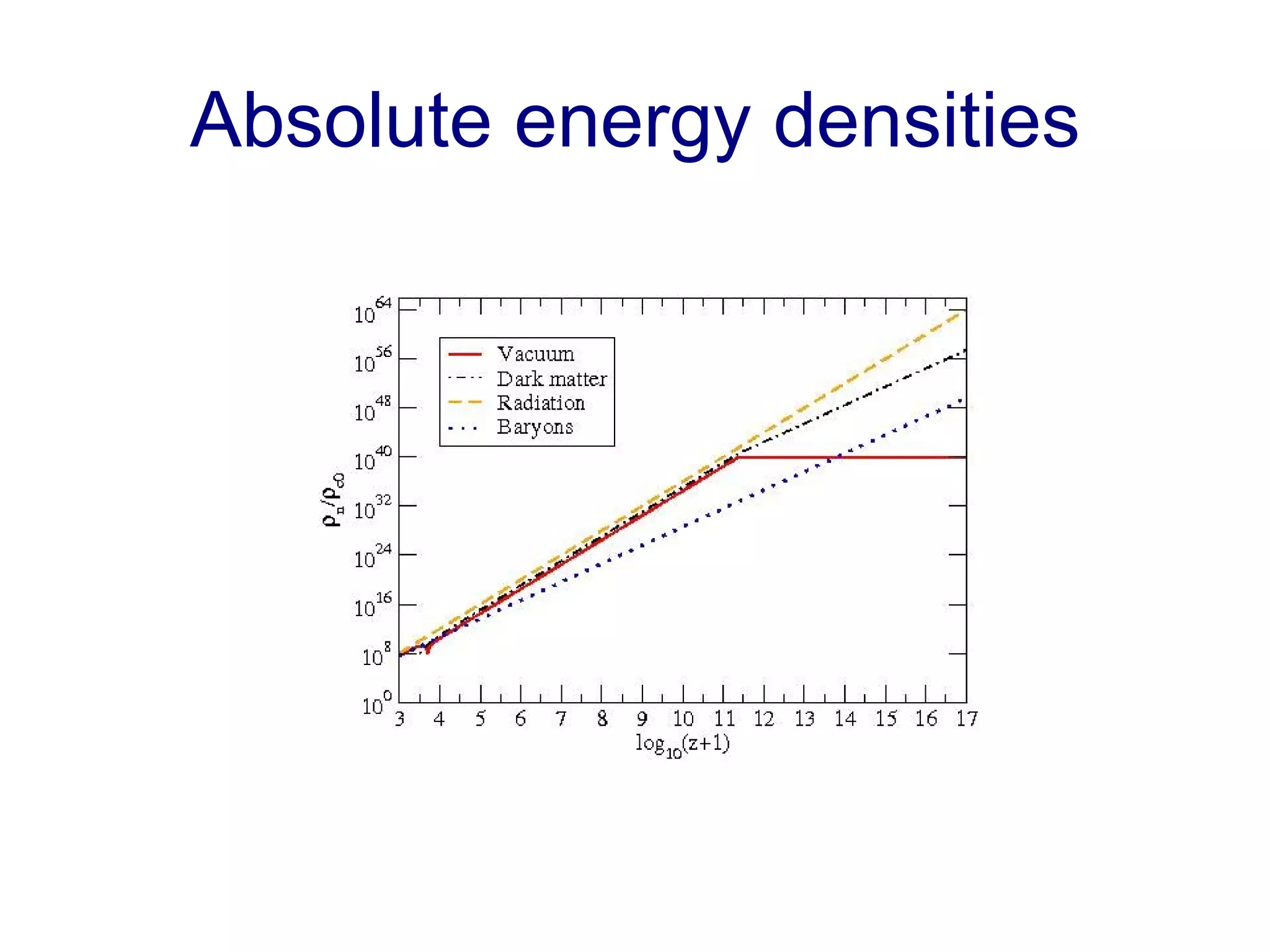

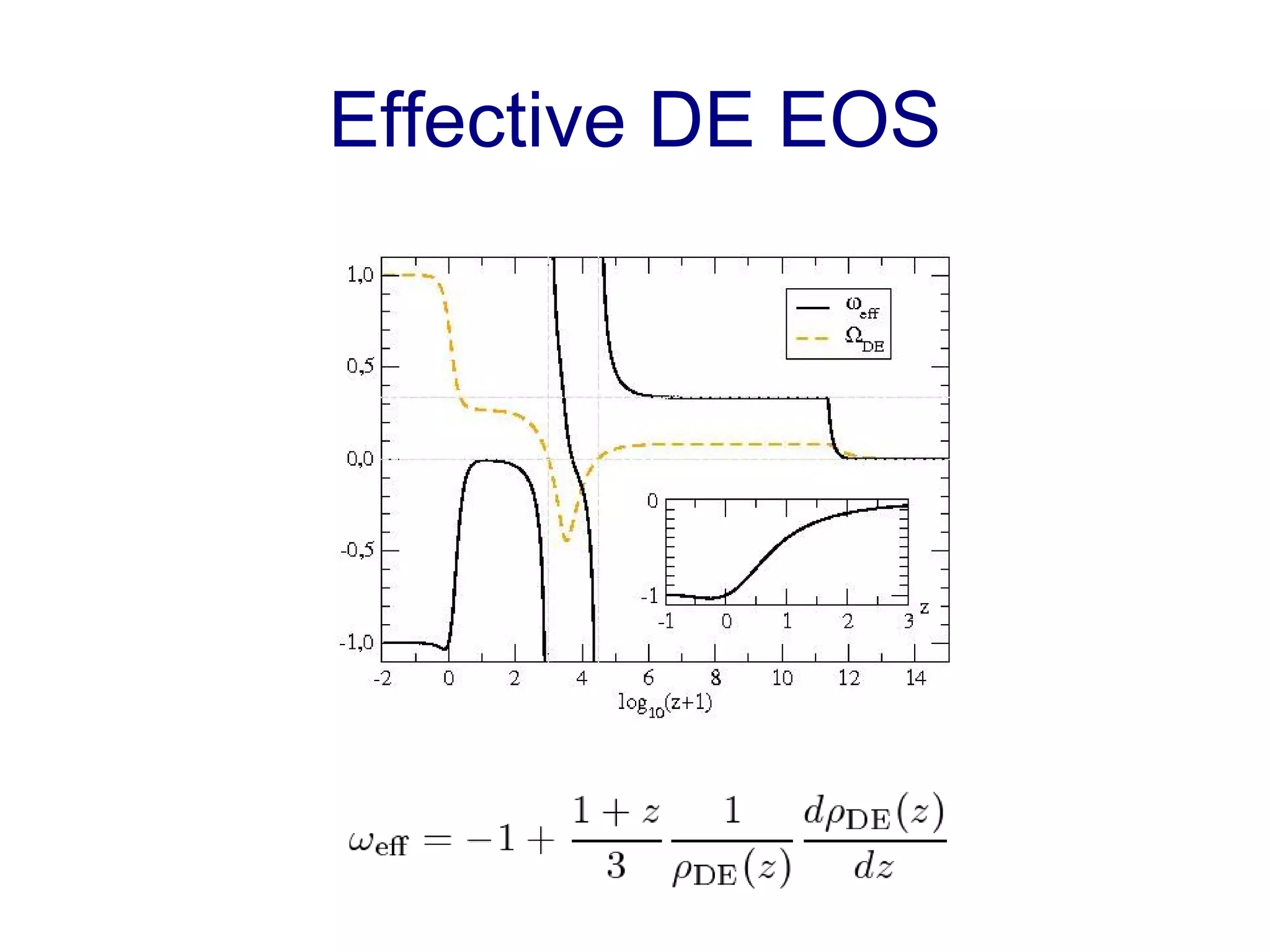

The document discusses the accelerated expansion of the universe and the cosmological constant problem, highlighting observational discoveries and theoretical challenges related to cosmic evolution. It reviews various cosmological models, observations such as supernovae and cosmic microwave background, and different approaches to resolving the cosmological constant problem. The interplay between dark energy, modifications to gravity, and other theoretical frameworks is explored, indicating ongoing debates and the need for precision cosmology to address these complex issues.