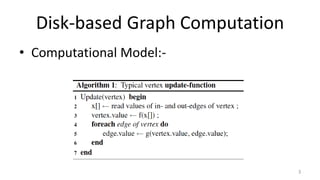

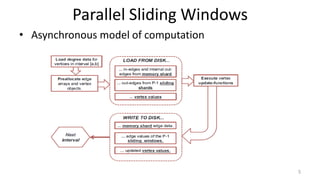

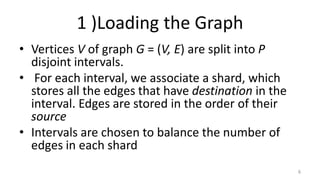

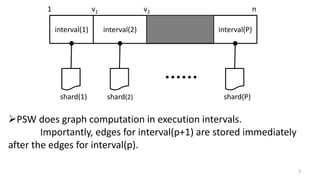

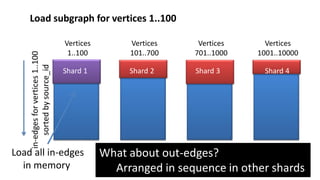

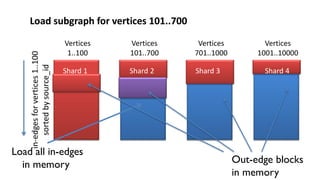

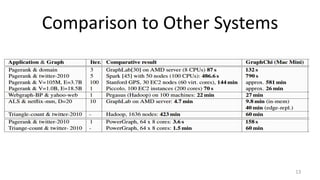

The document discusses GraphChi, a method for large-scale graph computation on personal computers, overcoming the challenges of scalable systems and graph partitioning. It introduces a disk-based computation model, parallel updates, and efficient data handling techniques that allow advanced graph computations without relying on cloud infrastructure. The approach demonstrates effective performance compared to traditional systems like MapReduce, enabling complex graph algorithms previously limited to cluster computing.