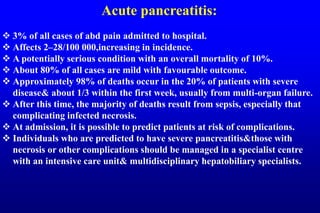

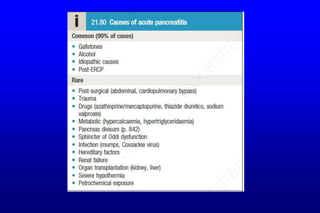

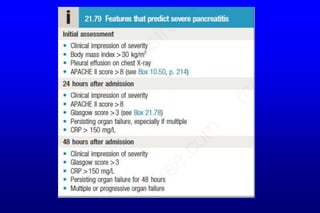

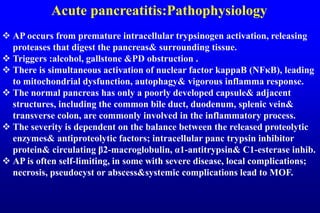

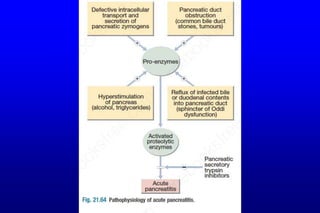

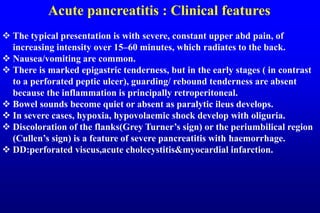

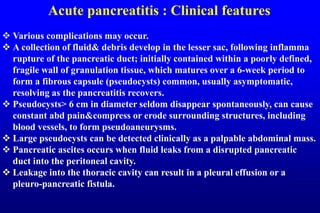

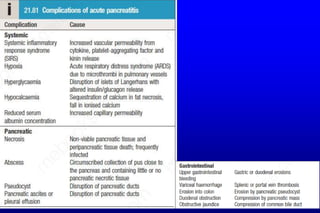

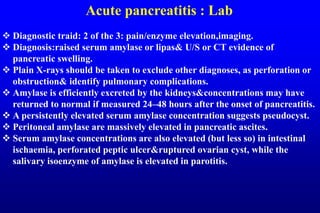

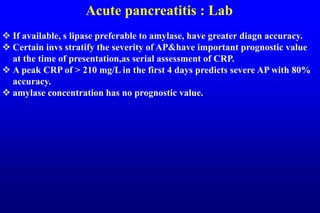

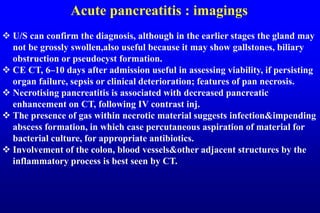

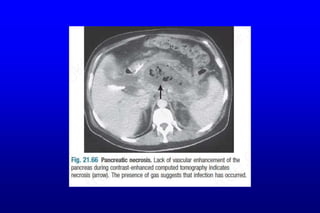

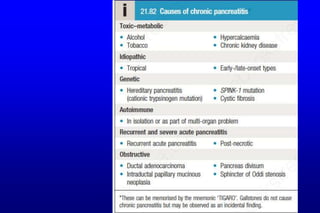

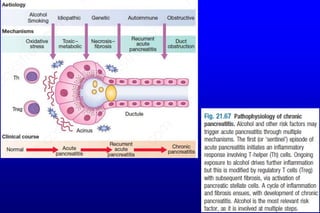

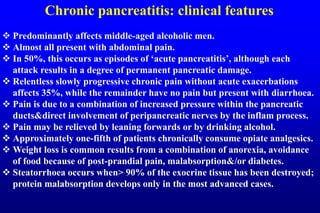

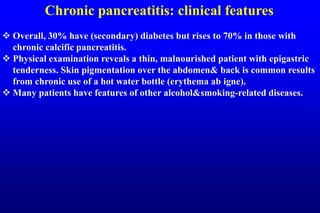

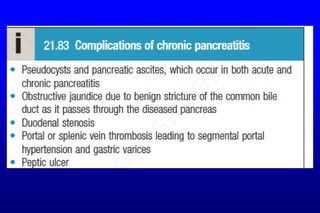

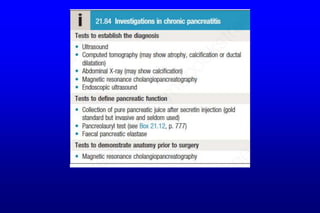

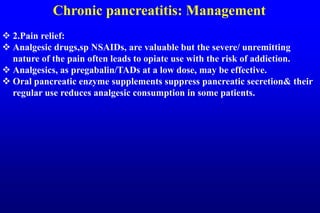

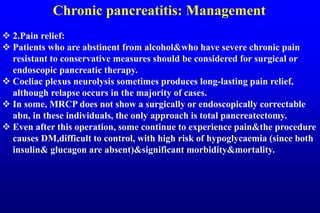

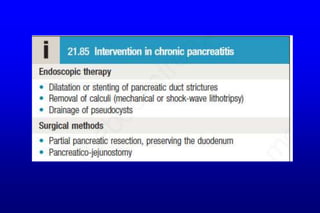

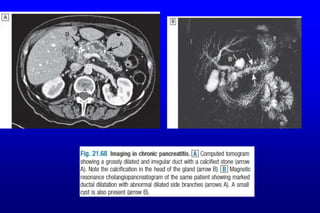

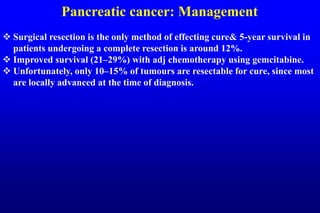

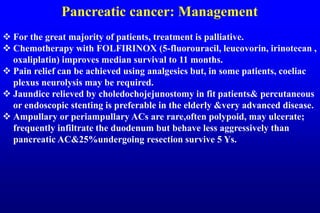

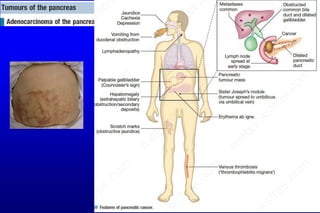

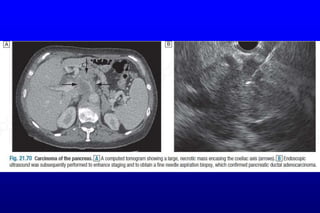

This document summarizes information about various pancreatic disorders including acute and chronic pancreatitis, autoimmune pancreatitis, and pancreatic cancer. It covers causes, pathophysiology, clinical features, investigations, and management of each condition. For acute pancreatitis, it describes predictors of severe disease and complications like pseudocysts. Management involves early resuscitation, nutritional support, treating underlying causes, and draining infected necrosis. Chronic pancreatitis is often due to alcohol and results in pain, malabsorption, and diabetes. Investigations aim to diagnose chronic pancreatitis and assess function and anatomy. Management focuses on alcohol cessation, pain relief, treating malabsorption, and complications. Autoimmune pancreatitis resembles cancer but responds to steroids