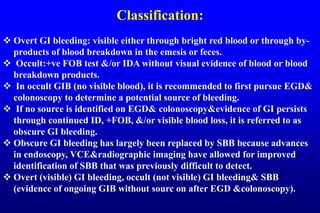

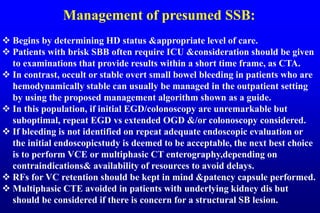

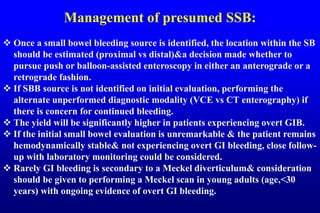

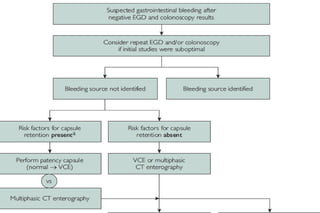

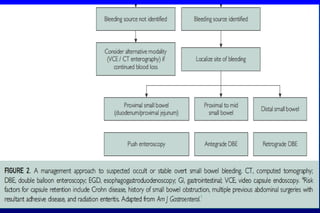

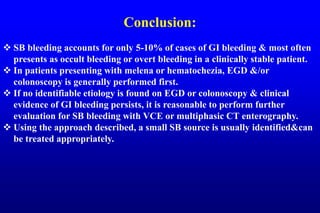

This document discusses the evaluation and management of small bowel bleeding (SBB). SBB accounts for 5-10% of gastrointestinal bleeding cases. The initial evaluation involves endoscopy of the upper and lower GI tract. If no source is found, video capsule endoscopy (VCE) or CT enterography are recommended to evaluate the small bowel. For brisk or unstable SBB, CT angiography may be used to localize the bleeding for potential embolization. Stable SBB can be managed with push or balloon-assisted enteroscopy to treat identified lesions. Following this algorithmic approach allows for identification and treatment of the small bowel bleeding source in most cases.