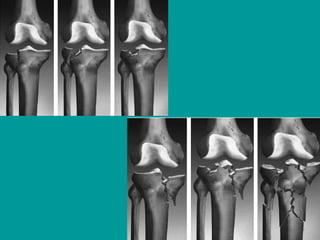

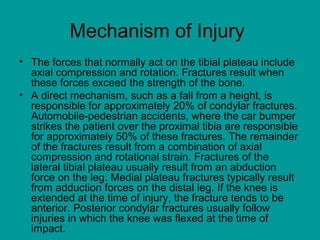

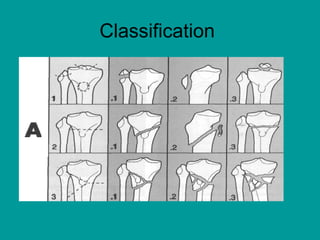

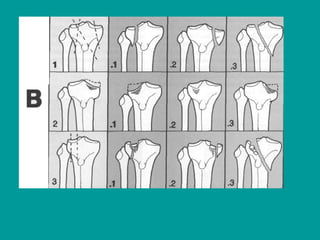

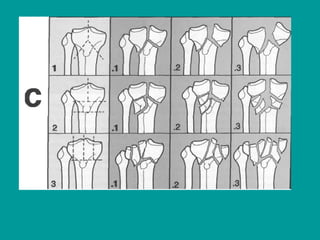

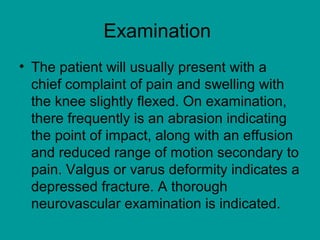

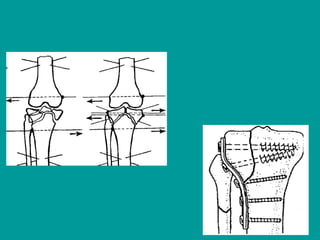

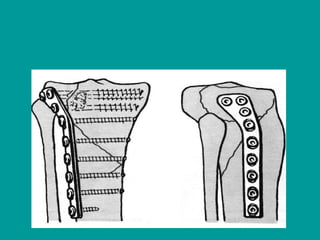

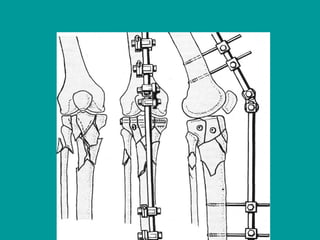

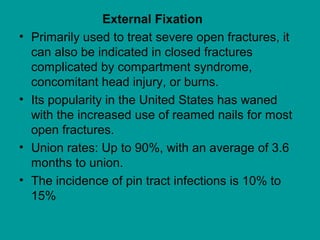

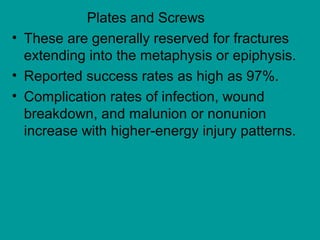

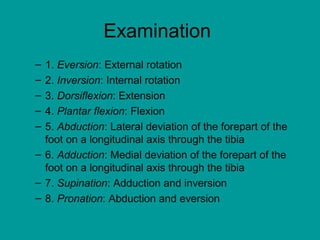

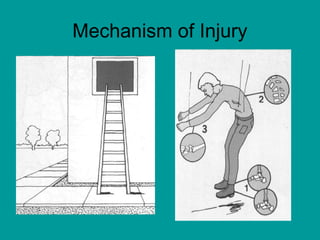

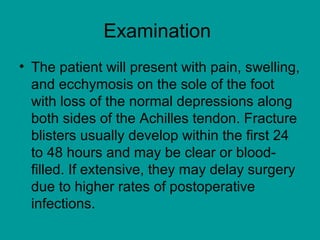

Proximal tibia fractures occur above the tibial tuberosity and can be articular or extraarticular. Mechanisms of injury include axial compression and rotation. Examination may reveal pain, swelling, and reduced range of motion. Imaging includes x-rays, CT, and MRI. Treatment is nonoperative for nondisplaced fractures and operative for displaced or unstable fractures to reconstruct the articular surface. Complications include loss of motion, arthritis, and deformity.

![Imaging

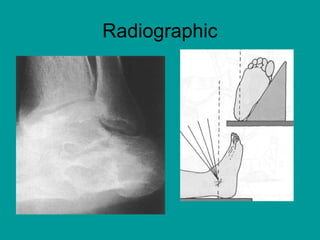

• Radiographic views (anteroposterior [AP],

lateral, Harris views)

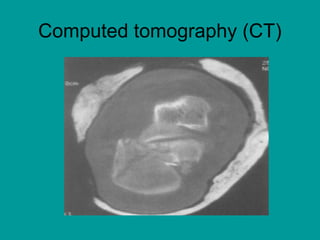

• Computed tomography (CT) has become

routine to fully delineate the extent of

fractures.CT is especially useful to the

surgeon planning operative intervention.

Plain radiographs alone fail to identify the

degree of fracture extension in almost half

of cases](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/8-170527193706/85/Fracture-of-Proximal-Tibia-71-320.jpg)