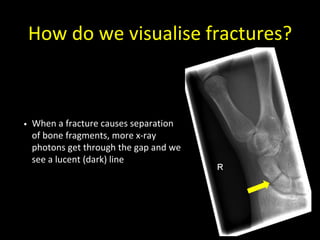

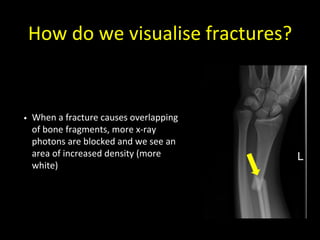

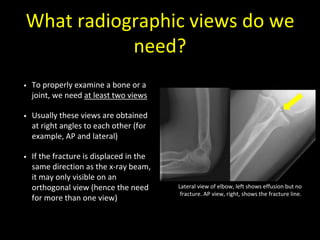

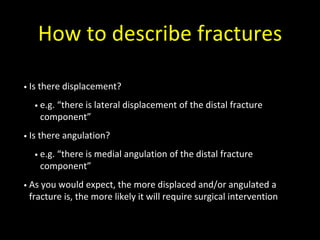

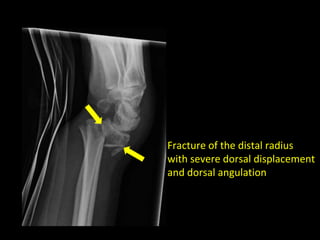

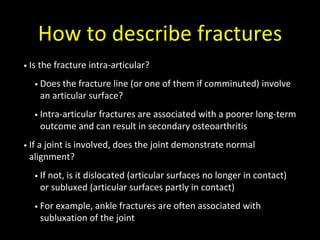

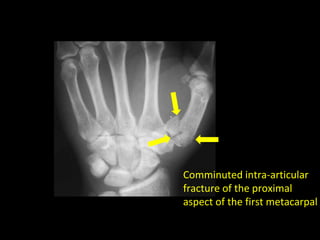

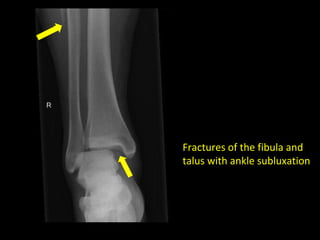

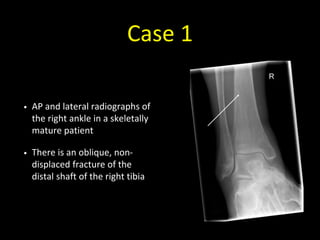

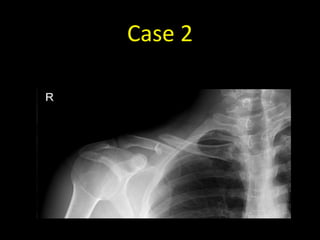

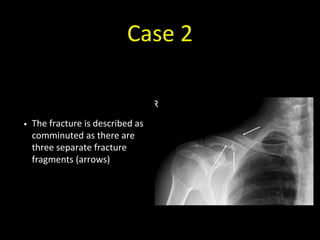

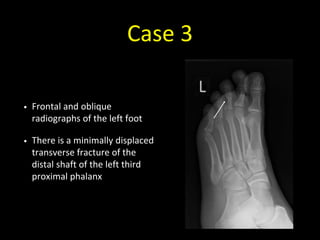

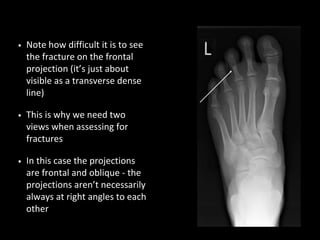

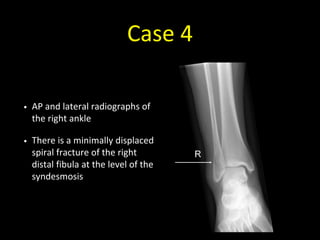

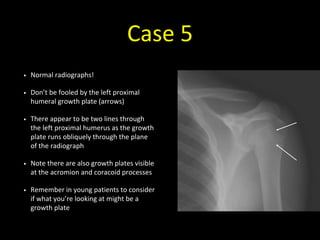

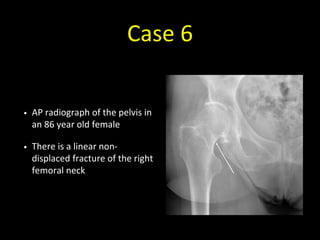

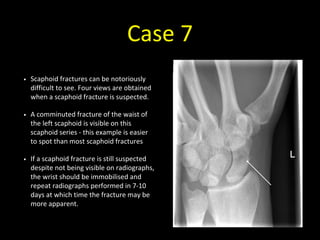

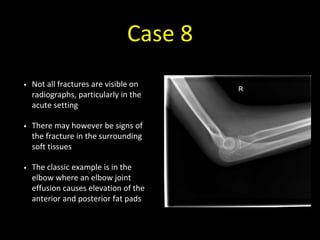

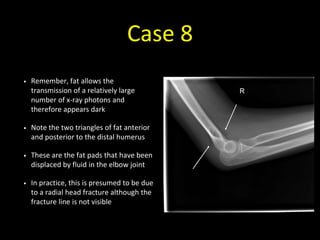

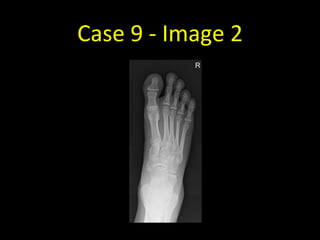

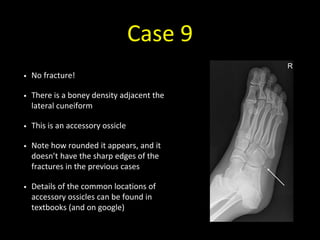

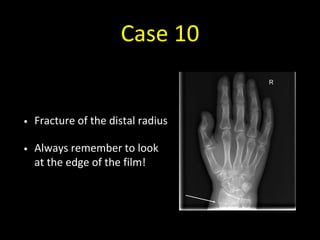

The document provides a comprehensive guide for medical students on interpreting fractures through radiographic views and descriptions. It emphasizes the importance of obtaining multiple views for accurate diagnosis, understanding fracture terminology, and being aware of normal variations that can mimic fractures. Additionally, it includes specific case studies for practice in applying these concepts to real situations.