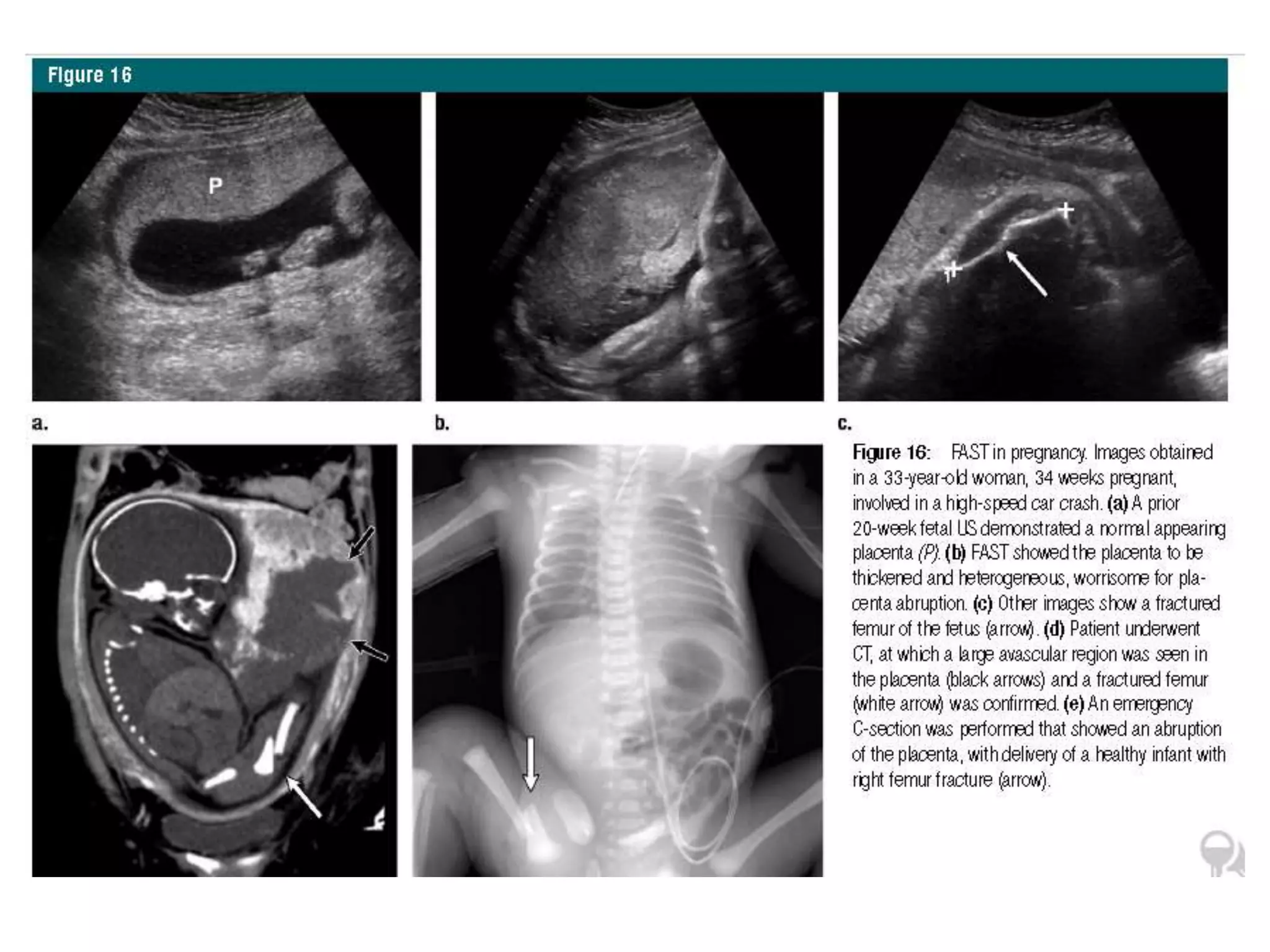

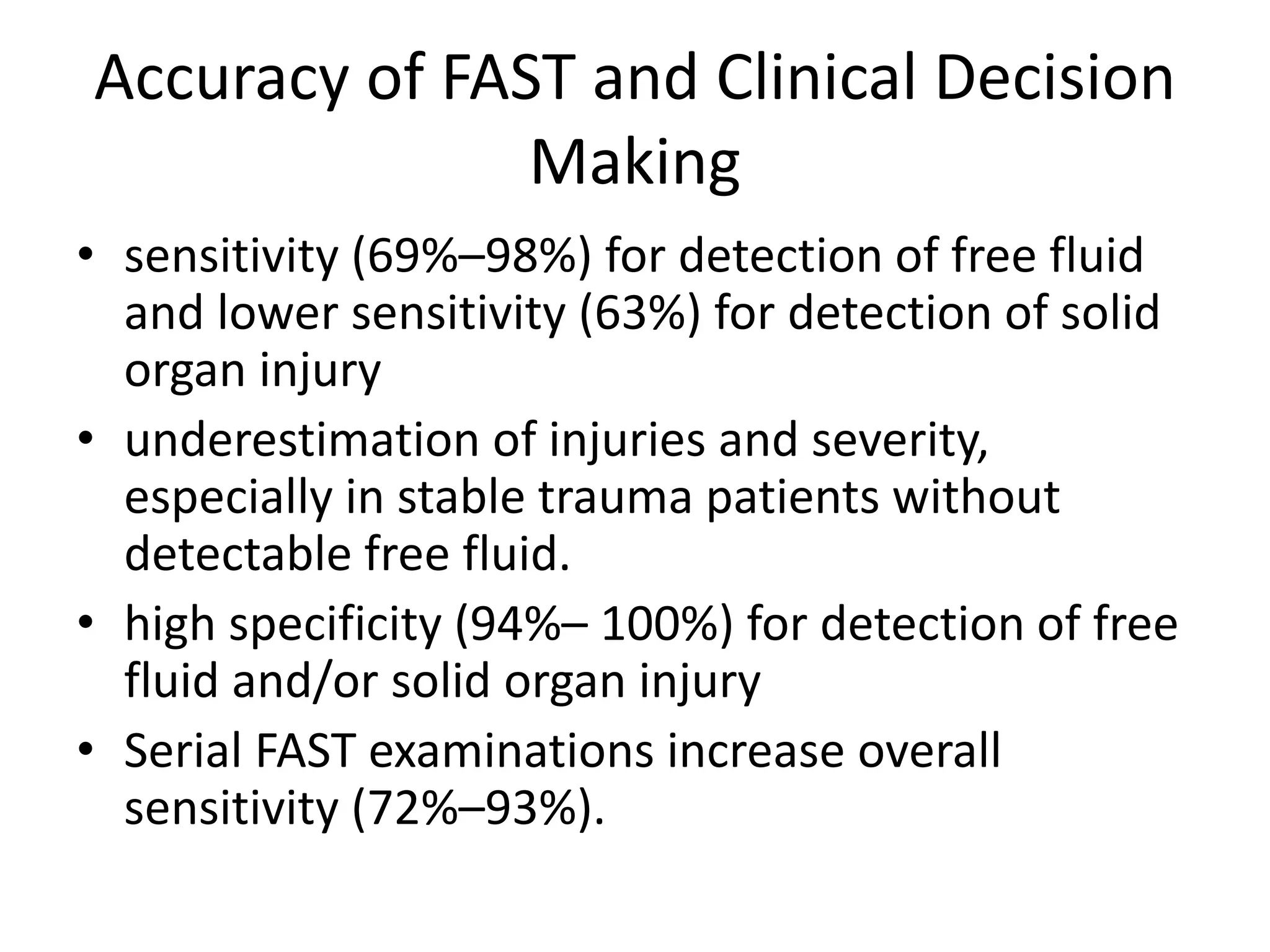

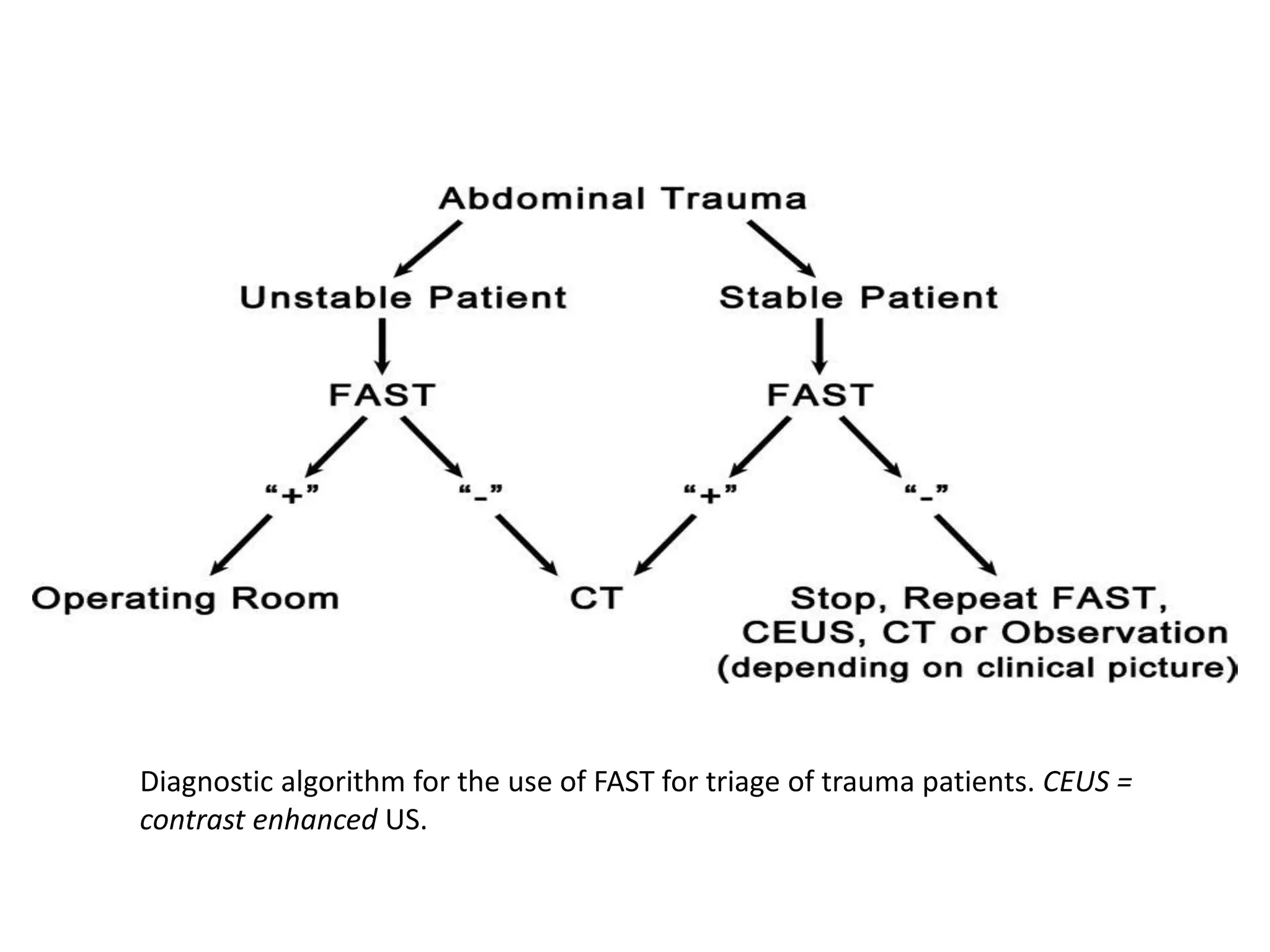

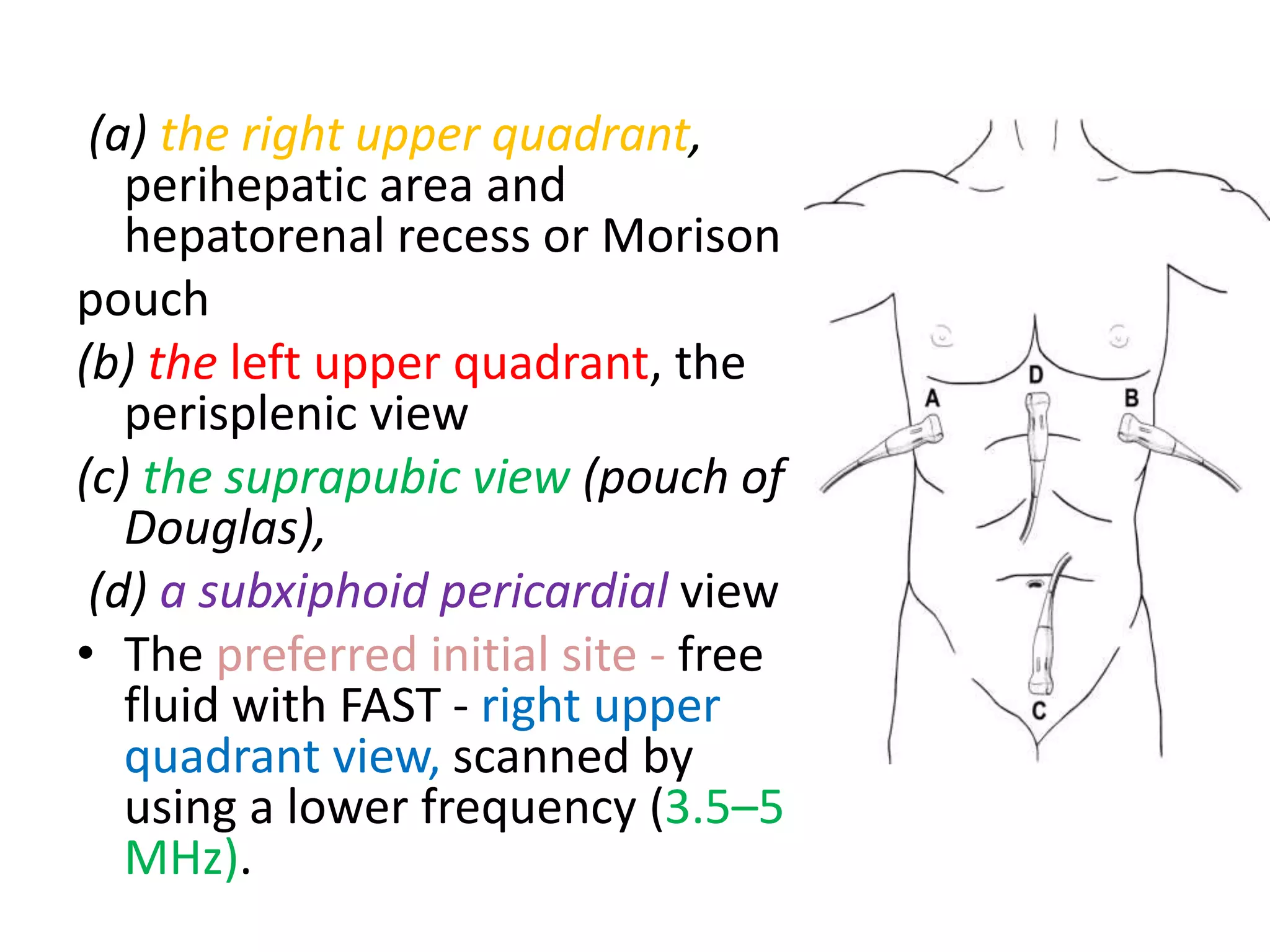

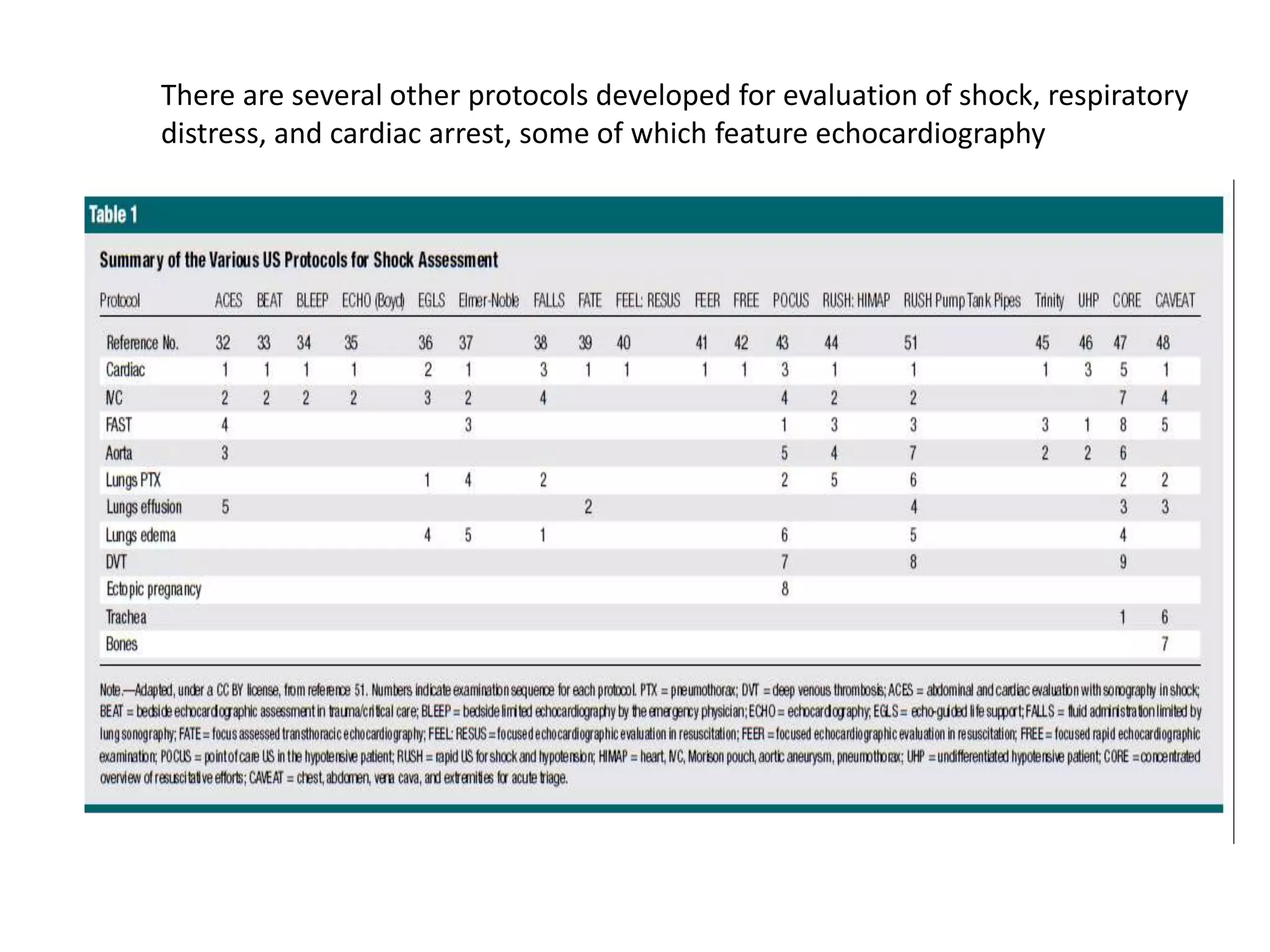

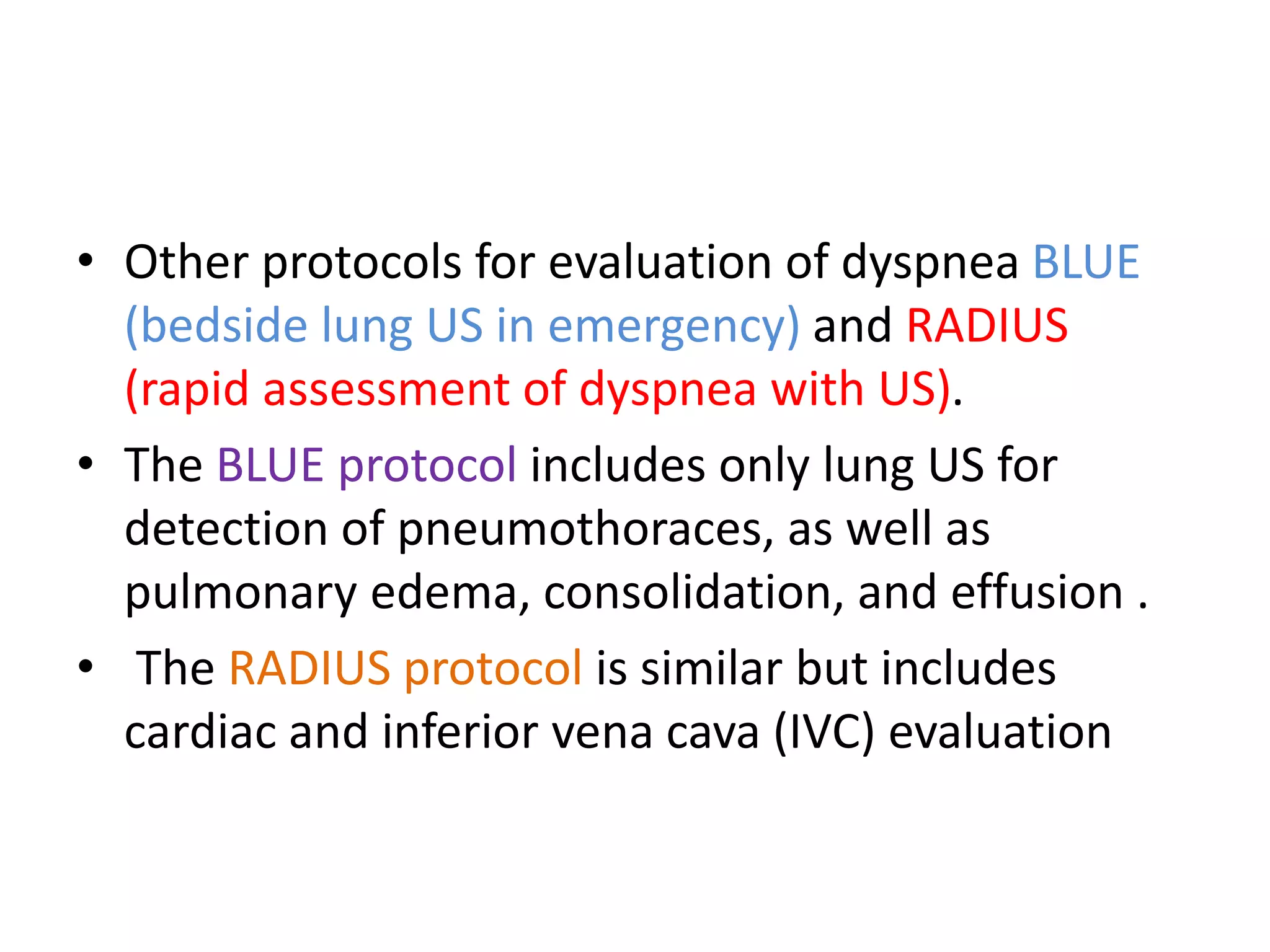

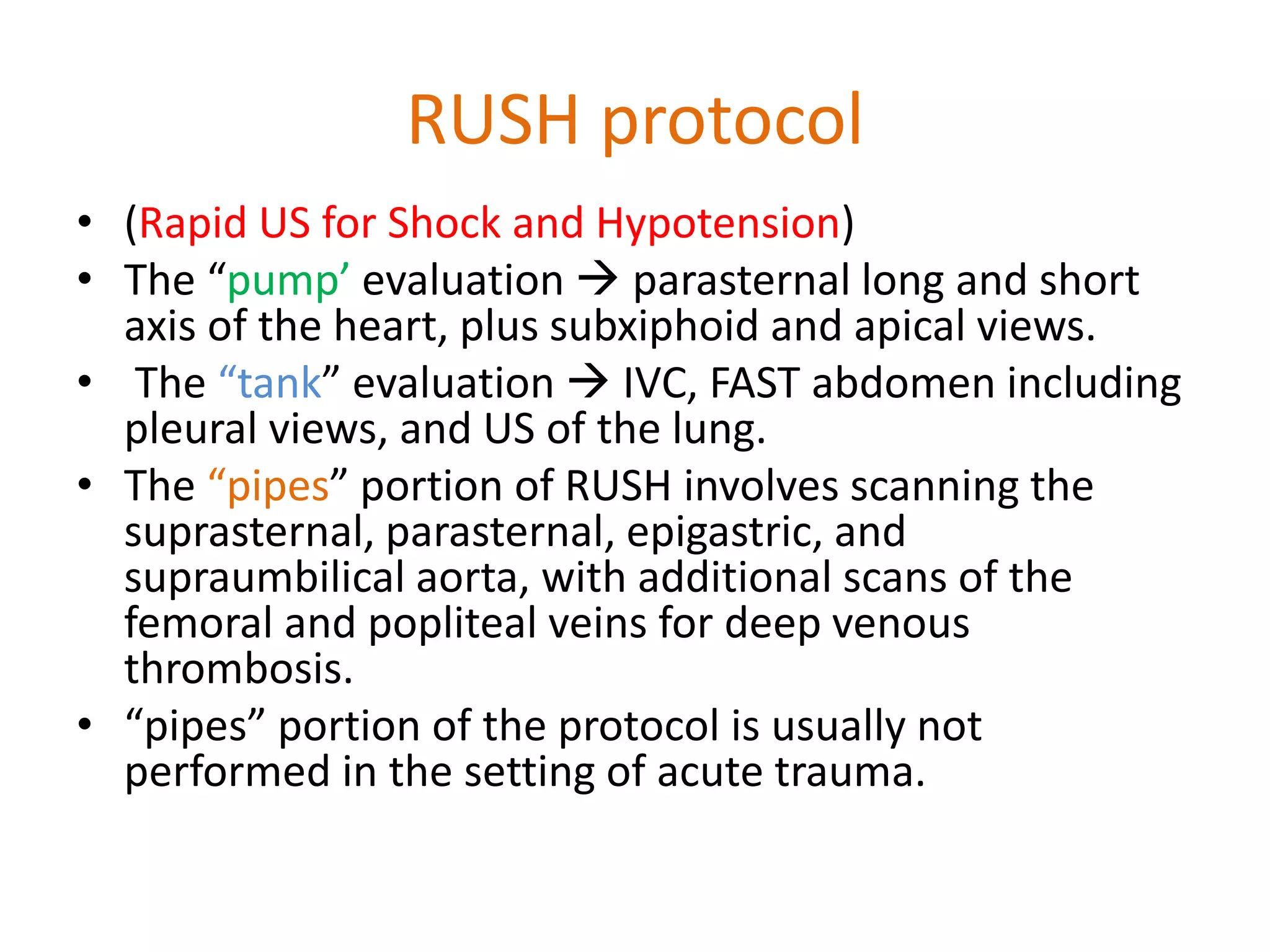

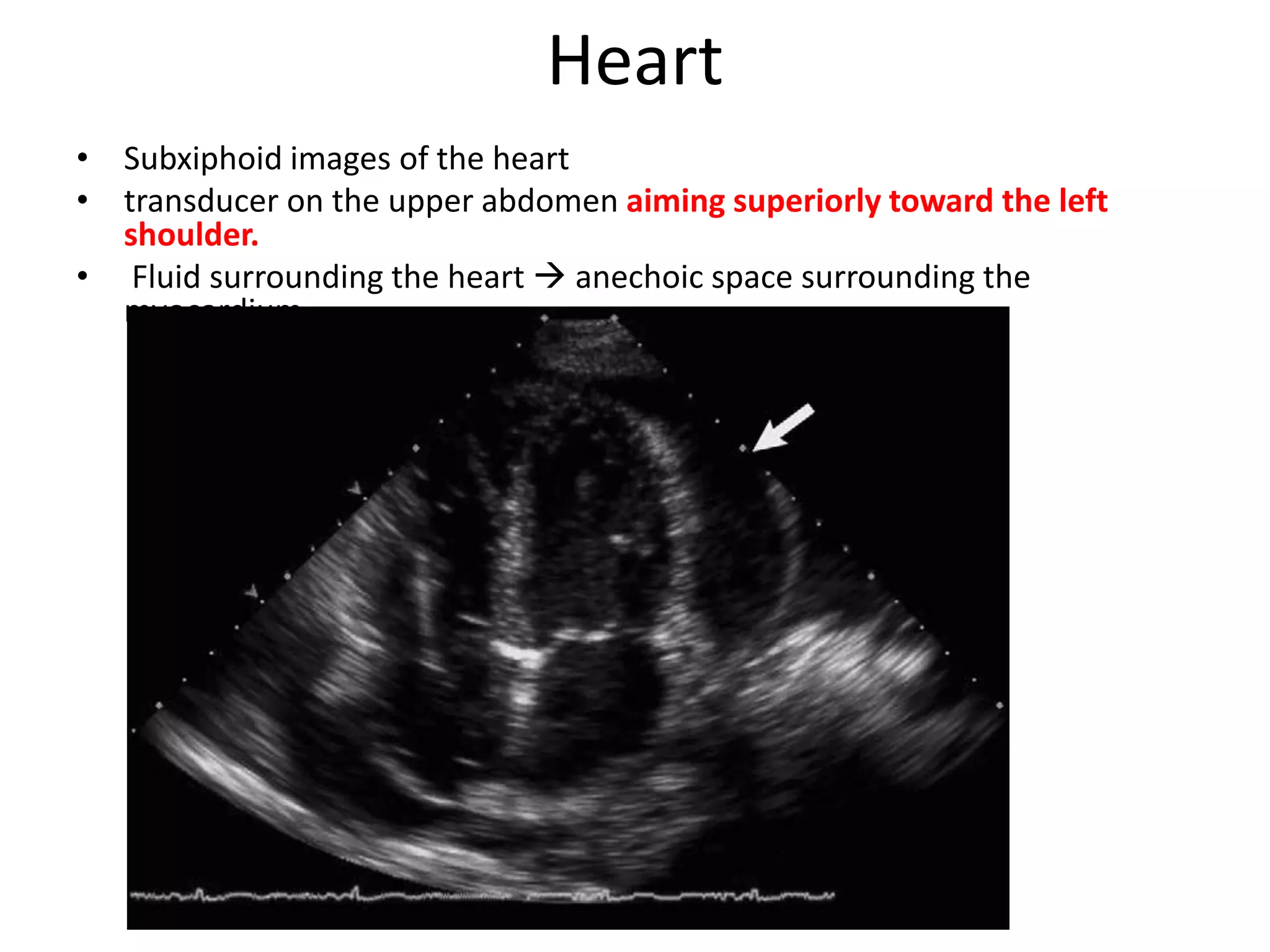

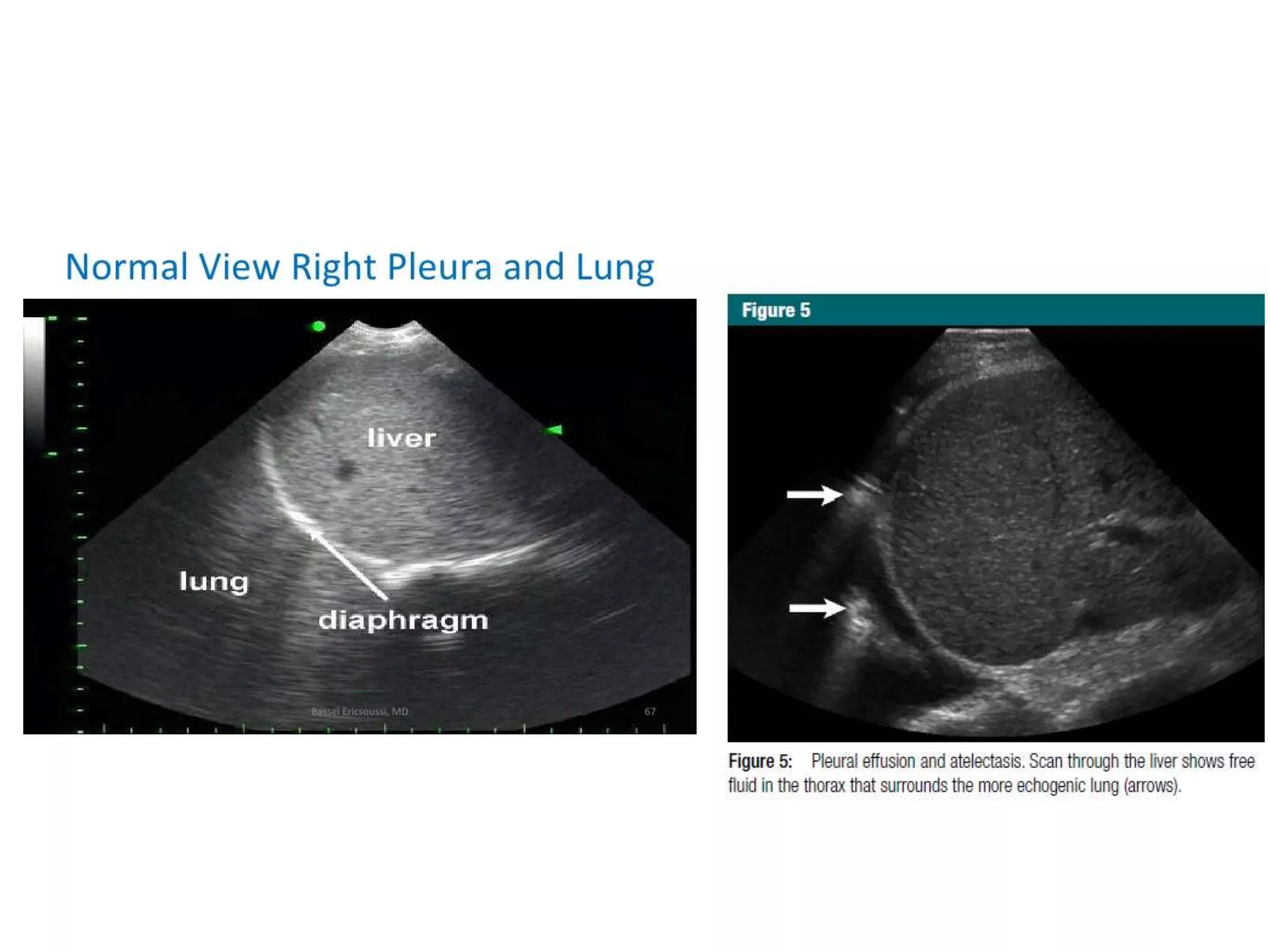

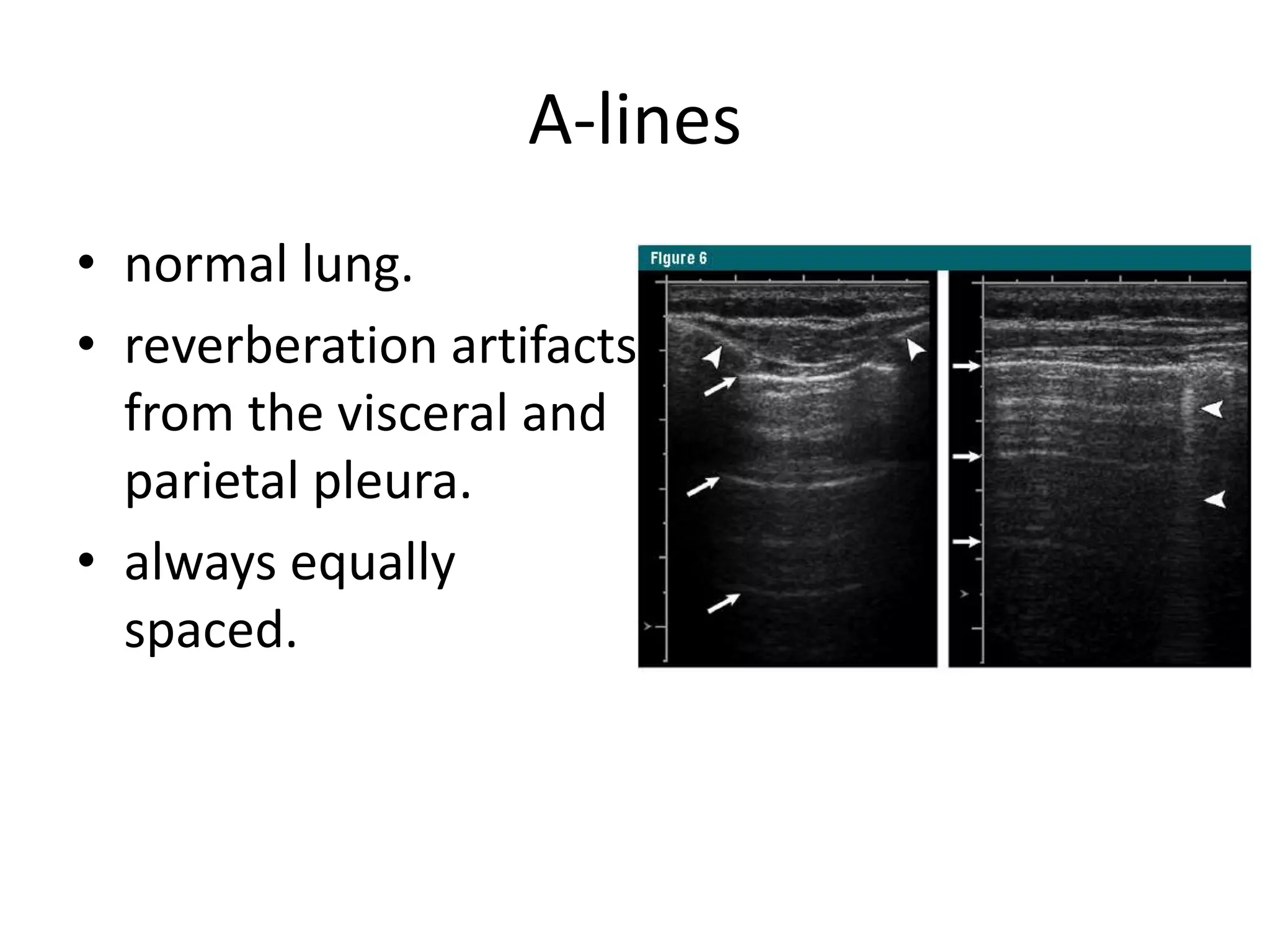

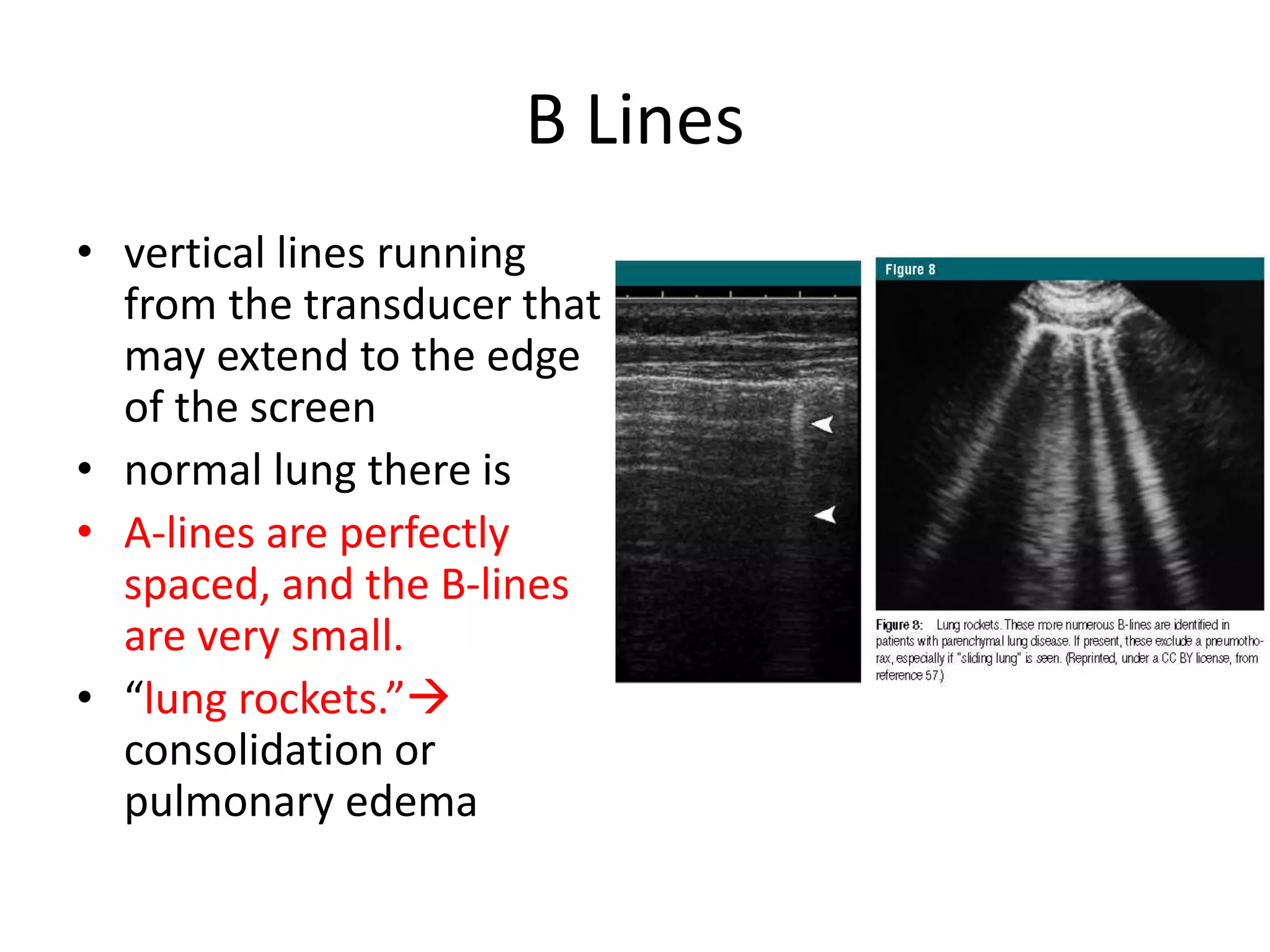

The document discusses the Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (FAST) technique, including its evolution, accuracy, limitations, and newer protocols such as EFAST and RUSH. It highlights the utility of FAST in quickly identifying injuries, especially in hemodynamically unstable patients, while also noting its limitations in detecting certain injuries. Additionally, it emphasizes the application of FAST in special populations like pregnant women and children, as well as its future applications in prehospital settings.

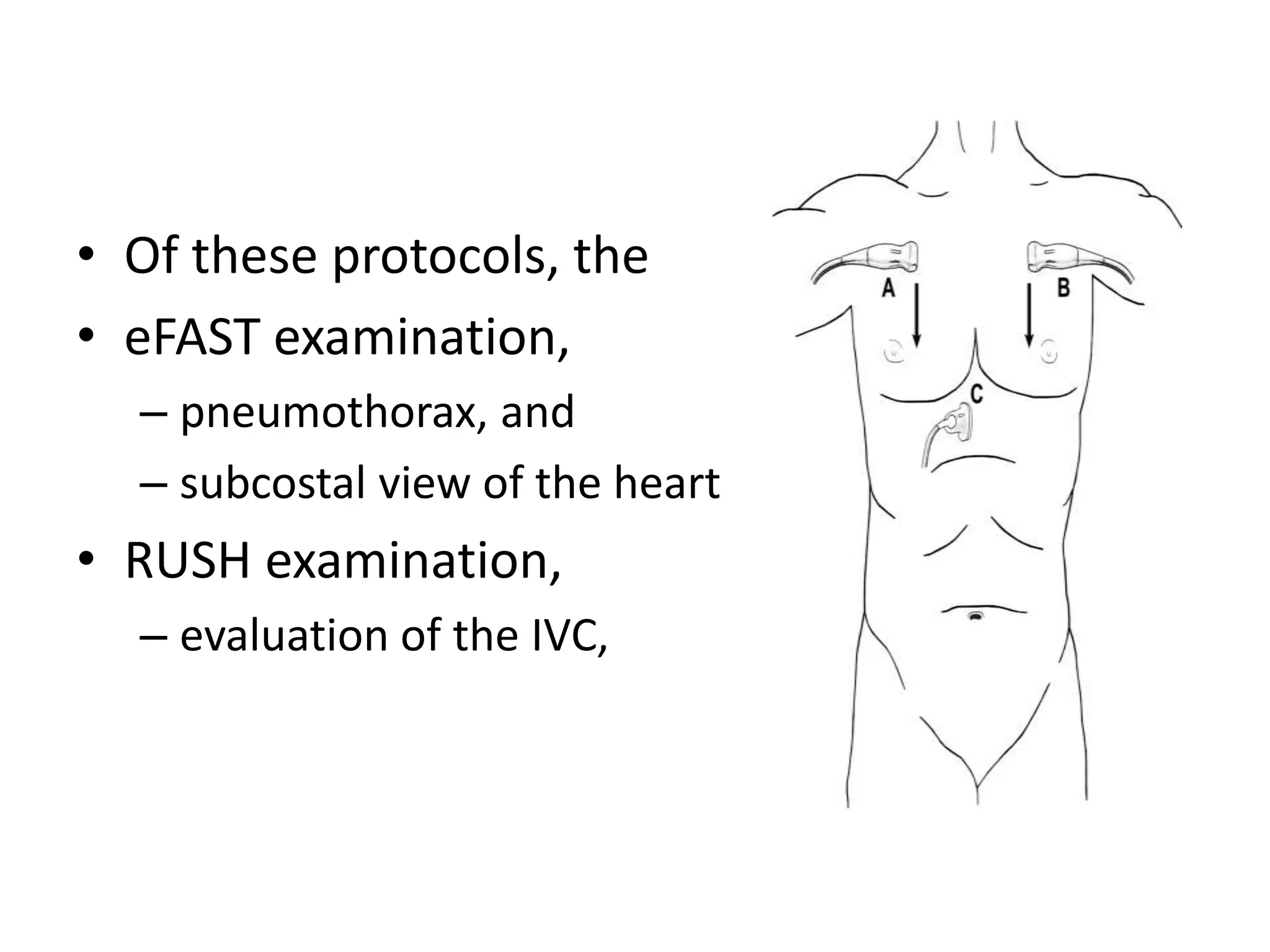

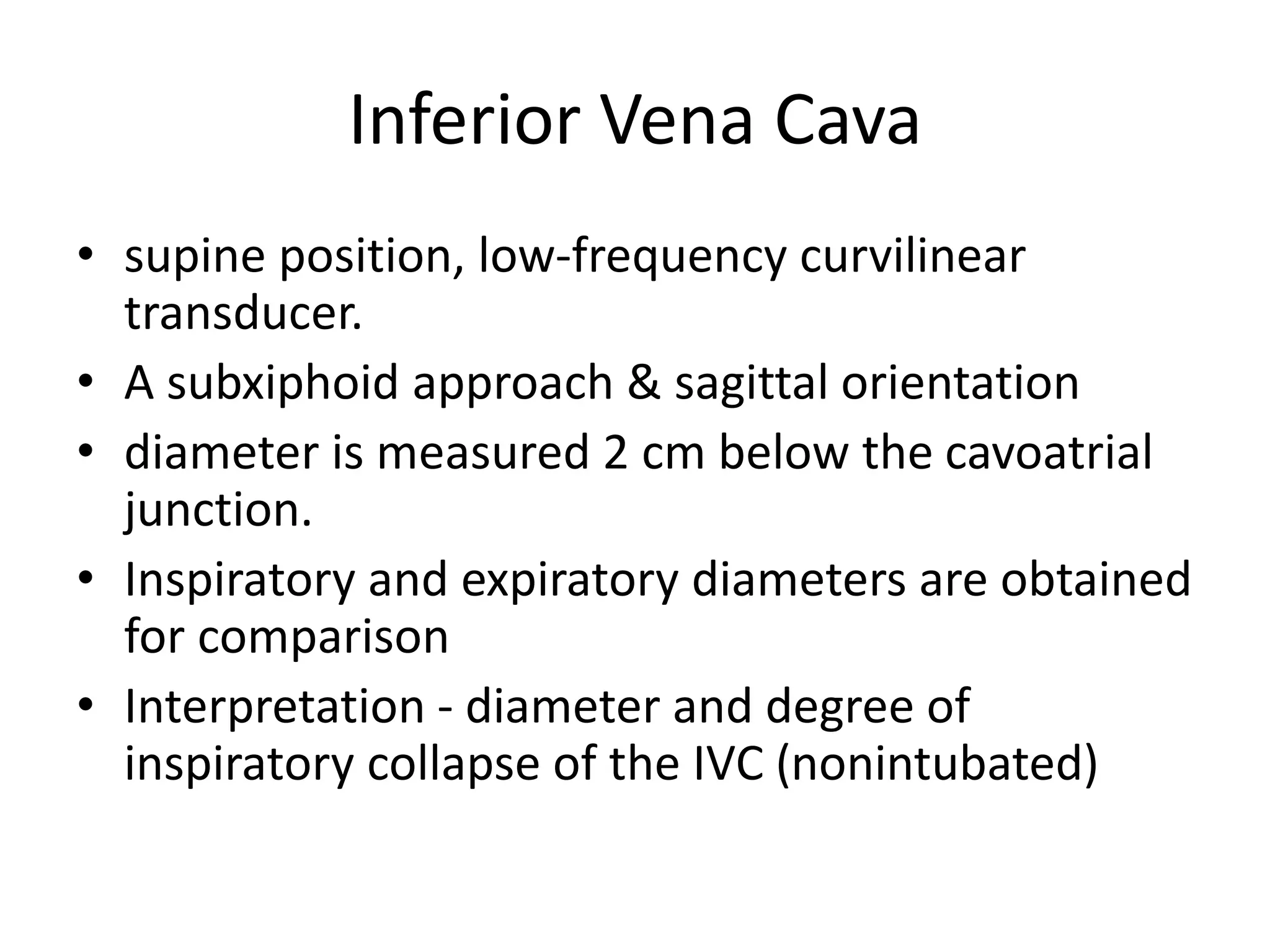

![• caval index : [(IVC expiratory diameter - IVC

inspiratory diameter)/ IVC expiratory diameter] x

100 .

• approaching 100% complete collapse and

likely volume depletion

• close to 0% indicates minimal collapse,

suggesting volume overload

• For trauma, simplest approach:

– if substantial collapse with small diameter (1.5 cm),

indicating volume depletion.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fastjc-170407151144/75/Focused-Assessment-with-Sonography-in-Trauma-FAST-in-2017-30-2048.jpg)