This document is a design report for an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) intended to help map glacial retreats in Greenland. It outlines the concept design process, including defining mission requirements, team member roles, and conducting a competitor survey. The preliminary and detailed design processes are then described, covering aircraft aerodynamics, structure, powertrain, materials, control systems, stability, weight, and performance. Testing procedures such as structural testing, aircraft scaling, stability testing, and flight simulation are also summarized. The report concludes with sections on aircraft costing, risks, and conclusions.

![Design Report

Absolute Zero

University of Swansea

Abstract

A detailed design report has been carried out for the purpose of creating an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)

for scientific research in the mapping of glacial retreats in Greenland. A comprehensive look into how and why

the aircraft looks and performs the way it does along with costings to determine the viability of creating a UAV fit

for this purpose.

1. Introduction

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) are becoming more

prominent due to their versatility and abilities to com-

plete tasks that man can not always accomplish. UAVs

are no longer only used for military applications but

are starting to become viable options for scientists and

hobbyists alike. UAVs or drones are divided into two

main categories, remote controlled or autonomous. For

the purpose of this design report an autonomous drone

was chosen due to the large range required.

Glacial retreats are slowly being recognised by the

general public as a problem due to what may happen

if glaciers start to disappear from around the world.

‘Glacier mass balance’ is the key to understanding glacial

retreats, this balance is the yearly addition of frozen

water to the yearly melted water determining whether

the glacier is healthy or in retreat.[1] If glaciers from

around the world were to disappear then it would leave

regions without fresh drinking water effecting animals,

wildlife and over a longer period of time sea levels.[2]

The aim of this project is to help develop a scientific

resource that allows glaciologists to map and keep record

of glacial retreats more easily and relatively quickly al-

lowing for preservation of these prehistoric glaciers.

2. Concept Design Process

2.1. Team Role Agreement

Based on individual’s strengths an agreement to

which roles each members would specialise in along with

a secondary role for support, Table 2 shows each member

and there specified subject area.

2.2. Mission requirements

As part of this design a guideline has been provided

with the minimum values required from the aircraft.

Certain values have been upgraded as it was felt the

benefits of producing an aircraft with certain capabilities

would be favourable to the mission.

Table 1: Mission requirements

Minimum desired

Take off distance 20m 20m

Range 60km 90km

Gust conditions 20 − 30km/h 30 − 40km/h

Cruise speed 50km/h 50km/h

Service ceiling 1000m 1000m

Payload 500g 1kg

cost £1000 under £1000

Reusability Yes Yes

Due to Greenland’s unforgiving weather and how

quickly weather fronts can form, were some of the key

factors in changing values in Table 1. Gusty conditions

are a major concern due to the mountainous regions

therefore the decision to design a more stable aircraft

was chosen. Range was increased incase areas of in-

terest arise during a mission along with an increase in

payload to lift better camera equipment or measuring

equipment. A challenge was set within the design to

create an aircraft under budget however this was not a

vital consideration in component costing.

2.3. Competitor Survey

To fully understand market needs and define a niche

in the market a competitor survey was conducted.

Table 2: Team Role Agreement

J.Jacob J.Johnson I.Milodowski D.Parish M.Rowland-jones M.Satha W.Shackley J.Tang

Specialisation Structure Materials & Propulsion Dynamics & Stability Aerodynamics Structural Weight & Performance Aerodynamics Control Systems

Secondary Role Dynamics & Stability Weight & Performance Structure Control Systems Aerodynamics Materials & Propulsion Structure Aerodynamics

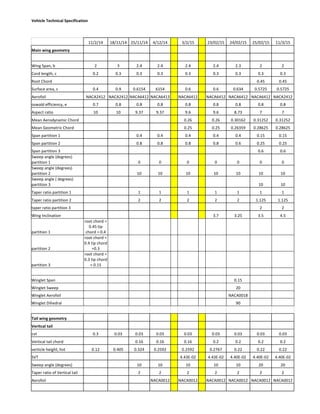

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/7fd4de17-6249-4c85-8b38-20b9bbf3e1cd-160112142054/85/Final-year-Design-Report-4-320.jpg)

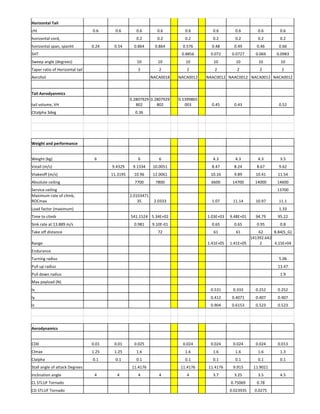

![Hirrus UAV [15]

Specifications Hirrus UAV

Weight 7kg

Max speed 130 km/h

Flight time 180 mins

Range 30km (auto pilot)

Payload 0.7kg

Service Ceiling 3 km

Aeromapper 300 [16]

Specifications Aeromapper 300

Wing span 3m

Fuselage length 1.23m

Material carbon fibre fuselage and fiberglass payload bay

Take off hand launch or launcher

Empty weight 3.6kg

Takeoff weight 5.2kg

Cruise speed 58km/h

Max speed 120km/h

Endurance 90mins

Cost £10, 200 all included](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/7fd4de17-6249-4c85-8b38-20b9bbf3e1cd-160112142054/85/Final-year-Design-Report-5-320.jpg)

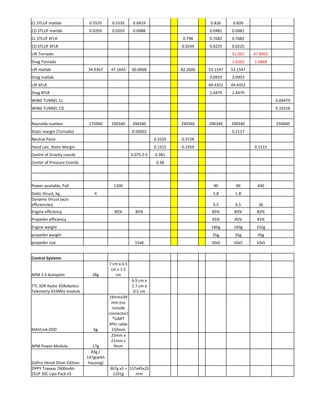

![Mugin 2600 UAV [17]

Specifications Mugin 2600 UAV

Wingspan 2.6m

Weight (No Engine) 6.5kg

Max Take Off Weight 15kg

Payload 4kg

Cruise Speed 120 km/h

Flight Time ~2 Hours

Cost £700 airframe

DuraFly Zephyr V-70 [19]

Specifications Zephyr V-70

Wing span 1.53m

Fuselage length 1m

Material Expanded PolyOlefin

Take off Hand launch or

launcher

Motor EDF 500 watts

Takeoff weight 1.15kg

Specifications Skywalker X8

Wing span 2.12m

Material Expanded PolyOlefin

Take off Hand launch or launcher

Motor 400-800 watts

Takeoff weight 3.5kg

Cost £110 empty shell

Specifications UAV 3000

Wing span 3m

Fuselage length 1.5m

Material Glassfiber/ply fuselage

Take off Hand launch or launcher

Empty weight 5.2 kg

Takeoff weight Dependant on motor up to 2

kg

Cost £ 180 empty shell

UAV

3000

[20]

Skywalker X8 [18]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/7fd4de17-6249-4c85-8b38-20b9bbf3e1cd-160112142054/85/Final-year-Design-Report-6-320.jpg)

![Figure 1: Positioning map detailing niches in the market

where this design hopes to sit

After initial research into each area multiple drones

were picked for further consideration. A quick table

detailing each aircrafts properties along with a picture

of each aircraft can be found above. From here a po-

sitioning map was created using a marketing tool that

allows users to find niches in the market. Fig1 shows

where each UAV fits in the market and where the aircraft

detailed in this reports aims to fit in.

3. Regulations

It is important to understand the regulations that

may effect the design of the UAV. Although the aircraft

will be flown in Greenland where the UAV regulations

are much more relaxed, it was important the UAV is able

to conduct missions within the UK for testing purposes.

Under the Civil Aviation Authority two key concerns

dictate the need for a permission of flight:

• Is the aircraft flying on a commercial basis (i.e

conducting ‘aerial work’)

• Camera or surveillance equipment fitted to the

aircraft within congested areas.

Although the aircraft will not be working on the basis

of monetary gain it will still be conducting work for an

organisation therefore a certificate will be required to fly

the aircraft. The second key parameter will however not

apply to this aircraft due to the surveillance or camera

equipment not operating in congested areas.[3]

UAVs are classified into 3 types based on overall

weight. Class 1 under 20 kg, class 2 between 20-150kg

and class 3 anything above 150kg. A certificate of Air-

worthiness is required for any UAV over the weight of

150kg, for the purpose of this project it will not be

required due to a very low weight under 10 kg.[4]

4. Preliminary Design

From detailed calculations and research, each area of

the conceptual design was looked into and accessed for

viability and purpose ultimately determining the final

aircraft at the preliminary stage.

4.1. Aerodynamics

4.1.1 Aerofoil selection

Reynolds numbers are a vital step in choosing an

aerofoil. A low reynolds number (Re) is favourable

due to low Re values experience more laminar flow and

therefore the aircraft will produce more efficient wings

generating lift.

Re =

ρV c

µ

(1)

From Equation (1) a value of Re = 250000 was found

allowing for the comparison of multiple aerofoils.

Figure 2: Comparison of multiple Aerofoils over four key

areas at the given reynolds number

The generation of the graphs in Fig.2 were produced

by Xfoil,[5] a program and analysis tool available for

aerofoil selection. The program was developed at MIT

and is only applicable if certain criteria are not met

i.e Compressible flow, Viscous Flow, etc... Based on

the low reynolds number and the values calculated by

Xfoils, the NACA 2412 was chosen due to its low drag

properties and relatively high Clmax. Initial studies into

the NACA 2412 using both Tornedo[6] and XFLR[7]

which will be discussed later on, yielded low values of

lift. Two possible options are to increase surface areas,

mainly wing span, or change the aerofoil to a higher

camber therefore generating more lift. The decision to

change to a NACA 6412 was chosen due to changing the

wing span by the amount needed would have resulted in

a difficult aircraft to launch.

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/7fd4de17-6249-4c85-8b38-20b9bbf3e1cd-160112142054/85/Final-year-Design-Report-8-320.jpg)

![4.1.2 Aerodynamic characteristics

To determine the aerodynamic characteristics of the

wing geometry and performance, multiple methods were

used. The advantage of using multiple methods meant

that these calculations could be made more accurate.

The following is a brief explanation of how each theoret-

ical method works.

Prandtl Lifting Line theory assumes that there is

only one horseshoe vortex for each wing segment, thus

making the wing finite. The theory predicts the distribu-

tion of lift generated along the span of the wing through

its three dimensional geometry. The strength of this

vortex reduces along the span. To ease calculations the

theory does not take into account the following; Com-

pressible flow, Viscous Flow, Swept Wings, low aspect

ratio wings and unsteady flows. The use of this theory

revolved around using different aerofoils from an aerofoil

generating software online known as airfoiltools.[8] From

this website estimations of Coefficient of lift properties

were taken from graphs which showed the characteristics

of each aerofoil. This was then introduced into the ap-

propriate equations to calculate the Coefficients of drag

and lift.

CL =

2L

ρv2S

(2)

CD = Cd0 +

C2

l

πeAR

(3)

Results from equations (2) and (3) can also be used to

determine the optimum angle of attack to fly at a given

wing geometries through the greatest CL/CD ratio.

Vortex Lattice Methods models the lifting surfaces

of a wing by assuming that the wing is an infinitely thin

sheet made of small vortices, this is influenced mainly by

the thickness of the sheet. It is an extension of Prandtls

lifting line theory however instead of the theory assuming

that there is a single vortex per wing segment a lattice

of these vortices are generated. To simplify calculations

the software makes the following assumptions; the flow

is incompressible, inviscid and non-rotational.

The lifting surfaces are assumed to be thin and the

influence of the thickness is neglected. It is also assumed

that the angle of attack and the angle of sideslip are both

negligible. Two different types of software were used to

do these calculations both with different advantages over

the other. Tornado which allows ease of design of the

wings through coordinate systems, which creates three

dimensional lifting surfaces such as the wings, horizontal

and vertical tails. However this software lacked the abil-

ity to create a fuselage and simulate how the fuselage

would interact with the lift generating surfaces. The sec-

ond was a program called XFLR5 which uses the same

interaction system as Tornado however has the ability to

create a fuselage and shows the effect this will have on

the wings and also has some very basic computational

fluid dynamics entwined into the software to produce

graphical representations of flows.

Table 3: Aerodynamics characteristics based on multiple

methods

NACA 2412 NACA 6412

Wing Span 3 2.4

Mean Geometric Chord 0.3 0.25

Reynolds number 290000 220000

Wing inclination 4 3.7

Tornado

CL 0.54 0.75

CD 0.009 0.024

XFLR

CL 0.44 0.8

CD 0.01 0.024

Finite wing method

CL 0.55 0.692

CD 0.02 0.05

Table 3 shows the two key iterations and the differ-

ence between both theories.

4.1.3 Aircraft changes

First iteration: Originally a weight estimation of 6kg

meant that the coefficients of lift and drag were calcu-

lated to produce enough lift for the aircraft to fly at

straight and level un-accelerated flight where lift is equal

to weight. Using a constant chord is often used where

low cost is important because of their ease to build and

manufacture, but they are less efficient in the outer sec-

tions of the wing. Through structural analysis the wing

span overall was not needed and could be shortened to

reduce loading factors caused by the span of the wing

and amount of material used.

Second iteration: With the estimated mass of the

aircraft still at 6kg, it was determined that changing

the aerofoil to a NACA 6412 meant that more lift could

be generated because of the increase in camber of the

aerofoil. This also allowed for partitions of the wing to

be tapered so to increase the aspect ratio of the wings

making them more structurally and aerodynamically ef-

ficient by reducing wing tip vortex strength. It was also

slightly swept back so as to increase the aerodynamic

stability. The change in aerofoil also meant that there

was now a larger CLmax available, this means that the

distance required to take off would be shortened, along

with better stall characteristics.

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/7fd4de17-6249-4c85-8b38-20b9bbf3e1cd-160112142054/85/Final-year-Design-Report-9-320.jpg)

![4.2. Structural Design

The design of certain features were governed by the

research from the aerodynamics, such as the wing shape

and aerofoil, and this evolved as time went on. The

main difference from the original wing concept was the

introduction of a taper ratio of 0.5 and increasing the

sweep to 10 degrees.

One of the conceptual designs for the internal struc-

ture of the wing was to produce a hollow shell with a

spar. This was produced to try and reduce weight while

remaining as strong as possible, however when trying

to optimise weight and structural integrity it was found

reducing the wall thickness of the aerofoil to reach an

optimal weight was problematic for structural loads.

It follows that a more classic ribs and spar configu-

ration has been adopted and the material selection has

increased stiffness and reduced weight. The tail geom-

etry again changed with the larger single-vertical tail.

Identical to the front wing, these were originally designed

to be a plastic shell but are now ribs and spars from

the original concept, the fuselage design has changed

substantially: removing the joined front and tail wing

construction as it increased weight too much and chang-

ing the battery choice altered the front hub. With the

shortened hub the design became structurally weaker

due to the point at which the tail of the wing cut into

the fuselage was near where the hub ended creating a

thin section of material, so a new design was looked into

with an additional aim of being more aerodynamically

suited to the flight parameters.

A high lift generating (HLG) fuselage was then de-

signed by using Mathematical optimisation technique

which then favours with more lift and low drag char-

acteristics at lower angles of attack, short landing and

take-off capabilities.[9] The main challenge in the fuse-

lage design was the space requirements and to get a

technical structure which withstands the load factors.

The largest stresses act at the joints where the wings are

connected to the fuselage, thus this area was strength-

ened with a larger wall thickness. Fillets were applied

at the sharper edges which again gives a uniform flow

of the loadings. Hence, the internal structure resists the

tensile and compressive loadings.

Fig 5 shows an overview of the aircraft design at

this stage along with placement of components. The

placement of each component was derived with the help

of control and stability to ensure a stable aircraft during

flight, see the section on stability.

4.2.1 Structural Diagram

A vital part of producing an aircraft is evaluating the

limitations. A load factor, n, can be calculated based

on equations (4) and (5). This graph shows three key

areas, the first is the stall properties of the aircraft this

is important when flying slowly. The top horizontal line

shows the structural limitations in-terms of manoeuvres,

the last line is the the vertical line where a maximum

speed is applied before structural loads become too high.

n =

q

W

S

CD0

k

(4)

n =

qπAe

W

S

[(

T

W

)max −

qCD0

W

S

] (5)

This can be depicted as a ‘V-n’ diagram found in

Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Structural limitations of the aircraft

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/7fd4de17-6249-4c85-8b38-20b9bbf3e1cd-160112142054/85/Final-year-Design-Report-10-320.jpg)

![Figure 5: Aircraft cross section along with component placing based on CG calculations

4.3. Powertrain

4.3.1 Motor selection

There are many types of engines ranging from elec-

tric propeller driven , diesel propeller driven, electric

ducted fan (EDF) and jet engines. Initially both jet

engines and electric ducted fan were ruled out due to

there lack of efficiency. EDF systems are designed to

operate at large RPM and produce large amounts of

thrust however, they are predominantly used in the RC

world as motors installed in model jet fighters reaching

large speeds and relatively low flight times, this was

decided, for the purpose of this mission inadequate. Jet

engines become very inefficient when scaled down to

the size we need, they also generally have high specific

fuel consumption compared to a small diesel or petrol

propeller driven aircraft therefore this motor was also

ruled out.

When comparing an electric motor versus a diesel or

petrol engine the main differences are in efficiency and

weight. With recent advances in brushless technology

electric motors can reach anywhere from 75%-85% effi-

ciency much higher than internal combustion engines.[10]

The weight of a petrol or diesel engine is much higher

increasing the aircrafts overall weight, not a desirable

feature. Due to the small thrust requirements produced

by weight and performance along with aerodynamics

results the choice for a mid powered electric engine was

chosen producing roughly 200 watts of power.

4.3.2 Propeller selection

There are two main aspects to all propellers, the di-

ameter of the propeller and the pitch of the blades. The

diameter of the propeller is the distance from tip to tip,

the pitch or twist of the blade is defined as the distance

the propeller would move the airplane forward in one

rotation in a perfect world. However this is impractical

as perfect conditions will almost never arise due to the

fact that propellers are never 100% efficient and this is

also considering an incompressible flow.[11] Although at

the speeds the aircraft is flying it would typically not

encounter compressibility effects it may be encountered

at the tips of the propeller.

The effects of the diameter of the propeller in general

will result in a larger amount of thrust produced by the

engine, whereas the pitch will increase the speed of the

aircraft. For example a small diameter coupled with a

large pitch will move faster through the air however only

move small amounts of air meaning it will be perfect

for small aircraft looking to move fast. A large diame-

ter propeller with a shallow pitch angle will move large

amounts of air meaning large amounts of thrust but the

shallow pitch angle means it will move through the air

more slowly.[11]

Based on Fig.6 and the more desirable shallow pitch

and larger diameter it can determined that a propeller

size of 10 × 5 is more desirable for the Greenland appli-

cation. The choice of propeller size also means that an

increase in torque benefits Take-off and Landing proper-

ties of the aircraft.

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/7fd4de17-6249-4c85-8b38-20b9bbf3e1cd-160112142054/85/Final-year-Design-Report-12-320.jpg)

![Figure 6: Propeller sizing guild based on engine size[12]

4.4. Material selection

The material selection was based on work completed

by the structural group along with the help of the Edu-

pack software. The structural design allowed for a maxi-

mum of 1000kg/m3

for critical components and a min of

100kg/m3

. From these values a list of possible materials

were chosen based of manufacturing routes, structural

limitations and overall viability for the aircraft. During

the detailed design phase materials will be assessed and

simulated to verify functionality. A short list of possible

materials for key component will be carried forward are:

• Nylon 6 10

• High density polystyrene

• hard wood, Spar

• Balsa wood

4.4.1 Aircraft changes

The conceptual design brought forward featured two

engines mounted on the underside of the wings. The

two engine configuration has since been dropped to a

single engine due to two main reasons, the first of which

is weight. Due to the relative lightness of the proposed

aircraft, having two very small engines produce the same

amount of thrust as having one slightly larger engine

with next to no real benefits with regards to excess

weight. The second reason is due to the effect it will

have on the range of the aircraft. Most brushless engines

will have a 75-85% efficiency therefore losses associated

with having two engines is much higher than just one

single engine. Not only do the losses in efficiency reduce

the range of the aircraft but due to each engine drawing

separate currents, the amount of energy needed for both

engines will far exceed that needed for one single engine.

Towards the end of the preliminary phase a prob-

lem was found in the design and material choice for the

fuselage therefore a complete overhaul of structure and

material choice was done which will be discussed later

on.

4.5. Control Systems

Due to the difficult nature of the mission a detailed

look into the flight controls and telemetry for the aircraft

has been conducted. The Greenland project requires an

aircraft that is autonomous and able to capture images

of the landscape it is flying through.

Multiple autopilot systems have been studied and

the AMP 2.6 board with GPS is a viable option at this

current stage. It includes 3-axis gyro, accelerometer,

magnetometer, barometer and other high performance

recording instruments that can be streamed live to the

ground station while in range or recorded while out of

range. The system also features an open source autopi-

lot systems using Invensenses 6 DoF Accelerometer and

Gyro MPU-6000.

Camera equipment is one of the most important as-

pects of design. The mission requires scientists to analyse

pictures captured from the aircraft to help map glacial

retreats. The initial design was to have two cameras, the

first facing forward and the main camera facing down

mapping the landscape. However due to the aircraft

changing from 2 engines to 1 engine, there is no longer

room for two cameras therefore one main camera will be

pointing down mapping the landscape. A GoPro hero 4

will be used as a high resolution device is needed.

Research on battery quantity and quality has been

carried out and there are clear advantages using LiPo

battery packs. Calculations have been conducted:

Batterylife =

mAh

mA

× 0.7 (6)

Based on Equation 6, where an efficiency of 70%

was used for environmental factors, and values found

by the propulsions section it was determined that two

high capacity LiPo batteries will be required for the

given flight time however three will be used for extra

range allowing for a safety factor and redundancies. The

batteries under consideration at this time is the Zippy

Traxxas 7600mAh 2S 1P 30C.

Table 14 shows the current selection of equipment

proposed for this mission along with dimensions and

weight of each component.

13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/7fd4de17-6249-4c85-8b38-20b9bbf3e1cd-160112142054/85/Final-year-Design-Report-13-320.jpg)

![Table 4: Control Systems

component Length (mm) width (mm) Height (mm) Weight (g)

Ardupilot 2.6 70 40 10 32

Turnigy MX-353S 17g Servo x 4 38 13 27 17 × 4

Zippy Traxxas 7600mAh Battery x3 157 25 45 367 × 3

Turnigy Dual Power Unit 100 50 20 89

Turnigy Plush 60A Speed Controller 80 31 14 60

Turnigy D3536/8 1000KV motor 52 35 35 102

3DR uBlox GPS + Compass 38 38 8.5 16.8

3DR Video/OSD System Kit N/A N/A N/A 100 − 150

Total 1594

4.5.1 Aircraft changes

Due to the amount of components to fit within the

fuselage it was required at an early stage to help re-

design the fuselage to accommodate all necessary flight

equipment. Although this can not be seen externally,

internally new compartments where created.

4.6. Stability

For an aircraft to be stable it must, after a period

of time, return to an equilibrium point in flight follow-

ing disruptive forces, such as a gust of wind or control

surface deflection. The first task with regards to the dy-

namic and static stability of the UAV was to determine

the static margin. The static margin is defined as the

distance between the centre of gravity and the neutral

point as a percentage of the mean chord. For an aircraft

to be statically stable, the centre of gravity must be

forward of the neutral point, therefore the static margin

must also be positive. Generally a margin greater than

5% [1] should provide sufficient stability.

An increase in angle of attack, α, should generate

a nose-down pitching moment, directing the aircraft

back towards equilibrium. In reverse too, a decrease

in α should generate a nose-up moment, directing the

aircraft once more towards stability.

dCM

dαα

< 0 (7)

At straight, level and steady flight the pitching moment

should be zero, as the aircraft should be in its equilib-

rium position. Therefore:

CMα(αα = 0) < 0 (8)

To calculate the static margin, this equation was used:

CMα = (h − hn)CLα (9)

From this equation, it can be seen that the centre

of gravity must be located in front of the neutral point

in order to achieve static stability. The static margin is

noted as: h − hn. To make the calculation of the static

margin easier, a MATLAB script was written, enabling

it to be calculated quickly during changes to the UAV

parameters.

Taking into account the configuration of the UAV

in the early design stages, the static margin was calcu-

lated to be 0.2359, 23.59%, demonstrating static sta-

bility. With the updated design, this was then revised

to 21.15%, matching also the values achieved from Tor-

nado. However, this value was deemed to be too high to

achieve sufficient manoeuvrability, and the target for a

static margin of around 15% was set, as UAV are usually

expected to have a static margin in the region of 5%

to 15%. To achieve this, the positions of the masses

within the airframe structure were shifted closer to the

neutral point. A static margin of 14.69% ended up being

calculated for the configuration detailed above. Table5

shows the change in CoG based on changes made to the

static margin.

Table 5: Centre of Gravity variation from leading ledge of

wings

Before After

X-CoG 30.7mm 108.46mm

Y-CoG 0 0

4.6.1 Aircraft Changes

The tail design for this aircraft will have a major

effect on stability of the aircraft during flight. Choosing

the correct configuration will make for a more stable

aircraft resulting in clearer pictures and therefore more

accurate aerial photography for the Greenland project.

The tail configuration carried forward from the con-

ceptual design was a twin tail plane, this design was

considered favourable at the time due to its larger surface

area and therefore increased stability during turbulent

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/7fd4de17-6249-4c85-8b38-20b9bbf3e1cd-160112142054/85/Final-year-Design-Report-14-320.jpg)

![5. Detailed Design Process

Moving out of the Preliminary design phase where

the aircraft’s overall characteristics have been decided

and early calculations have been conducted to ensure a

functional plane, the aircraft now moves into the detailed

design phase where parameters are refined to ensure ef-

ficiency and more desirable characteristics. During this

stage aircraft modelling followed by aircraft testing has

been accomplished to ensure an aircraft that not only

flies but handles correctly.

5.1. Aerodynamics

The aircraft wings underwent a large change in shape

for both aerodynamic and structural redundancy pur-

poses. This resulted in an overall aircraft weight reduc-

tion and more sleek aerodynamic geometry allowing for

reductions in drag, Fig.10 shows the evolution of the

aircraft wings from an aerodynamic point of view.

Figure 10: The first iteration is a simple wing, rectangular

in shape, this was then tapered at the ends in an

effort to reduce wing tip strength in the second

iteration. The last and final iteration has an

increased taper ratio along with a semi blended

wing, larger root cord, for structural reasons to

increase stiffness along with increase in lift and

aerodynamic properties.

During the detailed design stage of the project more

realistic software was adopted to verify lift and drag

properties. This was done to verify values that have

already been calculated and to fully understand the

aircraft.

5.1.1 Virtual Wind Tunnel

Virtual Wind Tunnel by Altair[13] is a Computa-

tional fluid dynamics software package designed for au-

tomotive vehicles. The key benefit of this software is

that it uses viscous flow, much more similar to the real

world. Gathering data from the virtual wind tunnel

allows for more accurate calculations for instance lift,

drag, pressure distribution and flow separation.

The Virtual Wind Tunnel works on the utilisation

of the Navier-Stoke equations. It is possible to calcu-

late the forces acting in the X, Y and Z co-ordinate

system, for the purpose of this study, lift, drag and cross

forces (usually negligible) respectively. The values found

are then normalised into values of CL and CD using

equations (2) and (3).

Generating a mesh is extremely important when

testing in the virtual wind tunnel, there are two basic

two-dimensional shapes that are used for meshing. The

benefits of using a triangle is that is it the simplest type

of mesh to create and has the ability to give a more

accurate concave or convex shapes. This is of great

importance when generating a mesh for the UAV as the

wings are in the shape of an aerofoil which is smooth,

any difficult to produce a smooth profile of the wing

which will greatly affect results.

Element size and the maximum deviation of elements

is important to create a fine mesh. The benefit of having

a finer mesh is that it will give more accurate results.

For this test the number of elements created is around

30,000. Which is more than enough for simple geometry

input, to achieve more accurate results a finer mesh

could be generated, however the finer the mesh the more

computationally heavy and time consuming it will be.

The mesh created for the virtual wind tunnel can be

found in Fig.11

Figure 11: Meshing of the aircraft for the Virtual Wind

Tunnel

17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/7fd4de17-6249-4c85-8b38-20b9bbf3e1cd-160112142054/85/Final-year-Design-Report-17-320.jpg)

![Multiple techniques were used and as a result, the

third iteration gave a better aerodynamic fuselage, both

in terms of fineness ratio and the tail taper ratio. With

the overall geometry of the fuselage determined, a model

was created ready for testing using a monocoque struc-

ture. Working with the material section it was noticed

that this design made it difficult to service components

and build in conventional managers meaning more com-

plex materials would be required resulting in a heavier

and less stiff fuselage. The fourth iteration was created

using a complete airframe design, where a tray of in-

ternal components could be placed within the airframe

for quick access and ability to swap trays for immediate

relaunch capabilities. Each iteration can be found in

Fig.17.

5.3. Motor

The Power-train in the aircraft has evolved multiple

times over the course of the design. With changes to

aerodynamic performance along with criteria set out by

weight and performance it was crucial that the correct

motor was chosen.

Based on the current drag estimates under straight

and level flight where thrust must equal drag equation

(14) was used to determine power required.

PR = Tv (14)

The value of 56 Watts is required for straight and

level flight, however this value is assuming perfect condi-

tions therefore equation (15) was used to include motor

efficiency, shaft efficiency and propeller efficiency.

PR = Tvηshaftηmotorηpropeller (15)

Based on equations (14) and (15) a total power of

171.5 Watts is needed during straight and level flight.

A certain amount of redundancy is required for take

off, strong winds and any other eventualities that may

occur during a flight. Table 9 shows the characteristics

of the chosen motor.

Table 9: Motor selection

Voltage 7.414.8V

RPM 1000 Kv

Max Power 430 Watts

Weight 102g

Using the current motor and Equ.(6) it has been

found that the aircraft will be able to sustain flight for

up to 1.7 hours.

The propeller, and engine type proposed during the

preliminary design is still fit for purpose therefore a 10×5

will be used along with an electric brushless motor.

5.4. Material

Edupack[?] was continuously used to determine vi-

able materials based on two key areas, weight and stiff-

ness. The two parameters are vital for wing design and

given by equations (16) and (17)

m = ALρ (16)

S =

CEA2

12L3

(17)

Equations (16) and (17) are substituted into each

other to provide a material index which can then be

applied to the Edupack software.

m = L

12L3S

C

×

ρ

E

1

2

(18)

The information in equation (18) provides important

values to achieve the stiffest and lightest material fit for

purpose, the value of ρ

E0.5 must be as small as possible.

This was applied to Fig.18 and is depicted as the

line that traverses the graph. Everything above this line

is a suitable candidate for material choice however the

higher the Young’s modulus the better. A criteria was

added so that the overall weight of the aircraft did not

rise significantly and therefore a maximum density of

2000 kg/m3

was chosen eliminating metals.

From Fig.18 the decision to use bamboo was adopted

for the main spar. This is due to the high stiffness and

relatively low density.

A light plastic film will be applied to the aircraft

and act as the skin of the UAV. This was chosen due

to its waterproof properties and the heat shrinking that

allows for exact moulding. Low density polystyrene will

be placed in-between each rib to allow for support of the

skin and ensure a perfect aerodynamic shape is kept.

5.4.1 Aircraft changes

Although the material selection has not had a major

impact on aircraft size or shape it has been a major

driving force to completely change the internal structure

of the fuselage. During the second iteration it was no-

ticed that parts were not easily accessible for repairs and

servicing (Fig.15). A larger problem was caused when it

was noticed that the fuselage would have to be manufac-

tured in a very specific way using certain materials that

where not feasible for this mission. Therefore a complete

overhaul of the internal structure of the fuselage was

22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/7fd4de17-6249-4c85-8b38-20b9bbf3e1cd-160112142054/85/Final-year-Design-Report-22-320.jpg)

![Figure 18: Edupack material selection softare[14]

done. Working along side the structure group a new

airframe system was implemented and allowed for more

material choice and manufacturing route.

The use of 3D printing is a large topic in the world of

manufacturing, the versatility of printing broken parts

along with upgrading components is endless. Therefore

incorporating this was felt as important especially if

scientists are in remote areas, all they would require is

a 3D printer to repair components. This move to 3D

ABS plastics was only possible due to the adoption of

an airframe instead of the heavier monocoque design.

Under testing the ABS plastic was able to withstand

the forces that would be expected from flight.

5.5. Control Systems

The process to determine the sizing of ailerons, rud-

ders and elevators was undertaken by using the Aerofoil

Flap Modeller script in Matlab. It takes the two dimen-

sional curves of the aerofoil used on the UAV, changing

some figures by percentage of the aerofoil chord length

to simulate a virtual control surface at a set range of

deflection angles, calculating the changes in lift coeffi-

cient and centre of pressure from the simulated control

surface.

Figure 19: CoP change during aileron deflection

The Aerofoil Flap Modeller script has been run twice

in order to size the ailerons, rudders and elevators. Fig.19

relate to the aileron sizing; in Fig.19, it indicates that

a smaller aileron with a 20% of the chord length, has

smaller changes in centre of pressure as it deflects, while

it is still generating sufficient lift coefficient changes to

roll the aircraft. The smaller change in centre of pres-

sure is desirable because it does not cause huge changes

in drag produced at the aileron, it will give the air-

craft a benefit in terms of power consumption during

manoeuvring.

23](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/7fd4de17-6249-4c85-8b38-20b9bbf3e1cd-160112142054/85/Final-year-Design-Report-23-320.jpg)

![The same method was used to calculate elevator size

and yielded 50% length should be used for both elevator

and rudder configuration.

Two methods were used to calculate aileron size

based on the aerofoil flap modeller and the second based

on hand calculated that take into account roll rates and

banking moments.

To complete the hand calculations the following val-

ues where used, Wing span = 2m, Take-off weight =

3.5kg, Wing area = 0.5725m2, Aspect Ratio = 6.99, Ta-

per Ratio = 2, Horizontal tail planform area = 0.0983m2,

Stall Speed = 8.67m/s, and Bank angle = 10 degrees

turning in 2 seconds.

ClδA =

2CLawτCr

Sb

[

y2

2

+

2

3

(

λ − 1

b

)y3

]yo

yi

(19)

Equation (19) was used to calculate the roll moment

required for the aircraft, from this the position of the

inboard and outboard aileron should be 60% and 95%

of the wing span respectively. This gave rise to a value

of yi = 0.61m and yo = 0.95m. The difference of these

values allow for the aileron length of 0.34m and the

depth of the aileron was found to be 0.057m, Fig.20 is a

diagram of the ailerons.

Figure 20: Aileron sizing

The calculations fit with the aerofoil flap modeller

therefore these values were deemed satisfactory and

proved sufficient during flight testing.

The sizing for both elevator and rudder were done

on the same bases and yielded the Fig.21 and Fig.22

Figure 21: Rudder sizing

Figure 22: Elevator sizing

5.6. Stability

The XFLR5 program, as mentioned in section 2.1,

allows users to determine where avionics and flight in-

struments should be placed within the aircraft. Using

the measurements of the length of the fuselage that

have been provided, a model of the UAV has been cre-

ated in this software, the user is able to move different

components of the aircraft, the wings and weighted in-

struments within the fuselage. A 3D model has been

produced within the program to determine positioning

of component to enable the structural group to build

compartments for housing all the electronics. This in

turn enabled for a more stable aircraft, Fig.23 depicts

where components should be placed for stability reasons.

Over the course of the design multiple iterations

have been created. Changes in weight, structure and

components all upset the balance of the aircraft. The

re-calculation of the static margin along with a small

shift in Cog was needed to maintain the desired 15%.

The resulting calculations produced Table 10.

Table 10: Centre of Gravity position and component posi-

tioning from nose of aircraft

Distance (m)

CoG 0.48

Battery and camera 0.34

24](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/7fd4de17-6249-4c85-8b38-20b9bbf3e1cd-160112142054/85/Final-year-Design-Report-24-320.jpg)

![References

[1] Nichols.edu. Alpine Glacier Mass

Balance [Internet]. Available from:

http://www.nichols.edu/departments/glacier/mb.htm

[2] Thomas Mlg. Worldwide glacier re-

treat. RealClimate. available at

www.realclimate.org/index.php?p=129

[3] Caa.co.uk. Do I need a Permission for an

Unmanned Aircraft (UAS) — Aircraft —

Operations and Safety [Internet]. Available

from: http://www.caa.co.uk/default.aspx?catid

=1995&pageid=16006

[4] Unmanned Aircraft System Operations In UK

Airspace Guidance, CAP 722. 6th ed. CAA, 2015.

Print.

[5] Web.mit.edu. [Internet]. 2013 Available from:

http://web.mit.edu/drela/Public/web/xfoil/

[6] Redhammer.se. Tornado, the Vortex lat-

tice method. [Internet]. Available from:

http://www.redhammer.se/tornado/

[7] Xflr5.com. XFLR5 [Internet]. 2015. Available from:

http://www.xflr5.com/xflr5.htm

[8] Airfoiltools.com. Airfoil Tools [Internet]. Available

from: http://www.airfoiltools.com/

[9] High lift generating fuselage concept http :

//www.ijetae.com/files/V olume2Issue5

[10] Quantum Devices INC. Brushless Mo-

tors vs Brush Motors, what’s the differ-

ence? [Internet]. 2010 Available from:

https://quantumdevices.wordpress.com/2010/08/27

/brushless-motors-vs-brush-motors-whats-the-

difference/

[11] Brown, M. (2014). Sizing RC Airplane Pro-

pellers. [online] Hooked on RC Airplanes. Available

at: http://www.hooked-on-rc-airplanes.com/sizing-

rc-airplane-propellers.html

[12] Carpenter. P. RC Airplane Propeller Size Guide

[Internet]. Rc-airplane-world.com. 2015. Available

from: http://www.rc-airplane-world.com/propeller-

size.html

[13] Altairhyperworks.com. HyperWorks: Open Archi-

tecture CAE solution [Internet]. 2015 Available

from: http://www.altairhyperworks.com/

[14] CES Edupack. (2014). United Kingdom: Granta.

[15] Hirrus mini UAV system [Internet]. 1st ed.

Bucharest: TeamNet International S.A;

2015 [cited 8 March 2015]. Available from:

http://www.aft.ro/bro.pdf

[16] Aeromao.com. Aeromao - Aeromapper 300 [Inter-

net]. 2015 [cited 2 March 2015]. Available from:

http : //www.aeromao.com/aeromapper300

[17] 3. Fpvflying.com. Mugin 2600 UAV FPV

platform - FPV flying [Internet]. 2015

[cited 18 March 2015]. Available from:

http://www.fpvflying.com/products/Mugin-

2600-UAV-FPV-platform.html

[18] HobbyKing Store. Skywalker X8 FPV / UAV Flying

Wing 2120mm [Internet]. 2015 [cited 12 May 2015].

Available from http://www.hobbyking.co.uk/

[19] HobbyKing Store. Durafly Zephyr V-70 High Per-

formance 70mm EDF V-Tail Glider 1533mm (PNF)

[Internet]. 2015 [cited 12 May 2015]. Available from

http://www.hobbyking.co.uk/

[20] HobbyKing Store. UAV-3000 Composite FPV/UAV

Aircraft 3000mm (ARF) (EU Warehouse) [Inter-

net]. 2015 [cited 12 March 2015]. Available from

http://www.hobbyking.co.uk/

10. Appendix 1 (VTS)

32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/7fd4de17-6249-4c85-8b38-20b9bbf3e1cd-160112142054/85/Final-year-Design-Report-32-320.jpg)