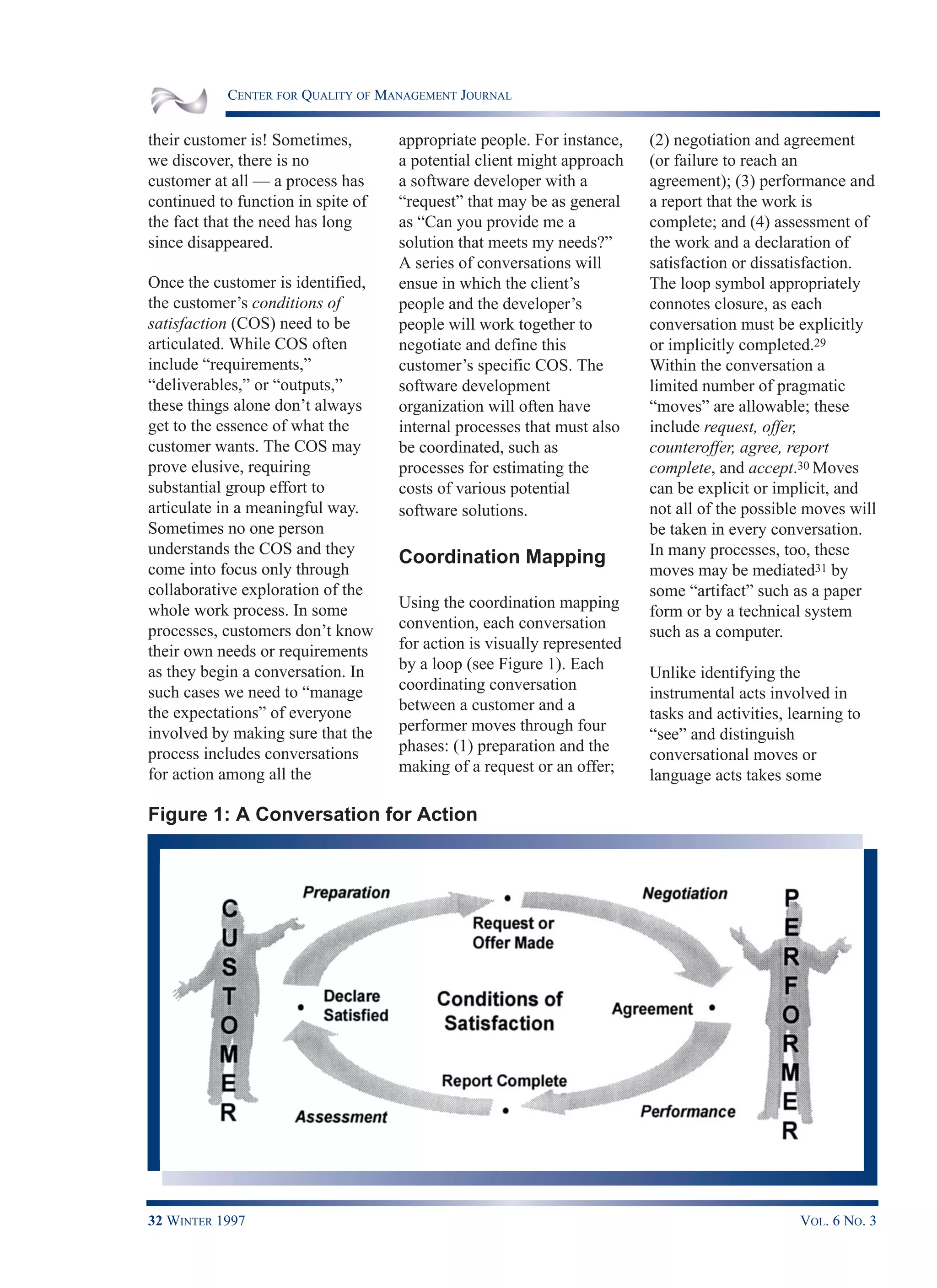

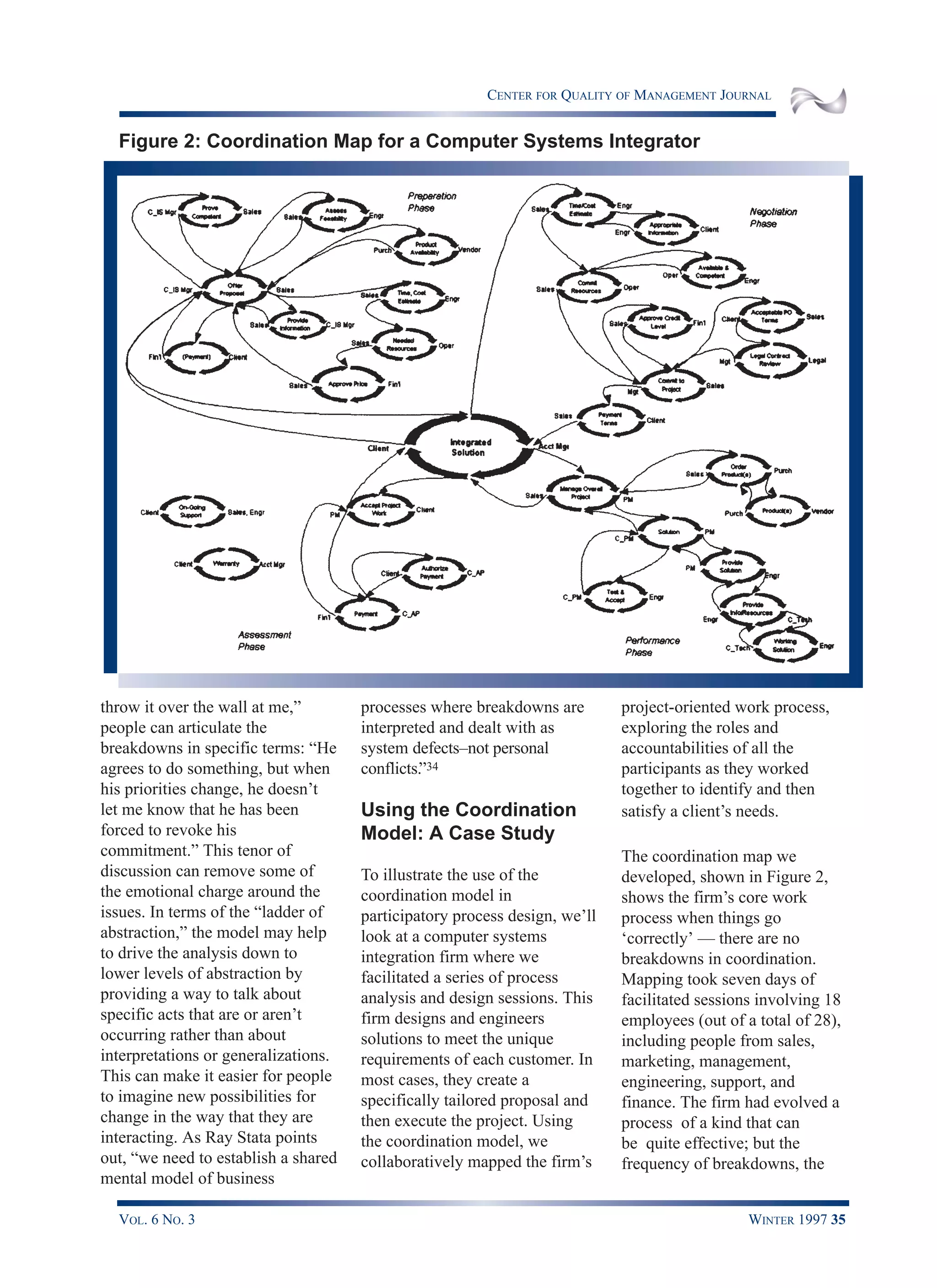

This document discusses process models and participatory design. It begins by describing different types of organizational processes, noting that "office" processes like research, development, design and planning are more difficult to rationalize than factory processes. It then discusses participatory design, which aims to actively involve process participants in work process design and improvement. A new process model called the "coordination model" is introduced, which views processes as networks of conversations among skilled individuals coordinating their actions. The document presents a case study where this model was used successfully in a participatory design effort. It argues the coordination model provides benefits for quality-oriented organizations by supporting flexibility, variability and broad participation.