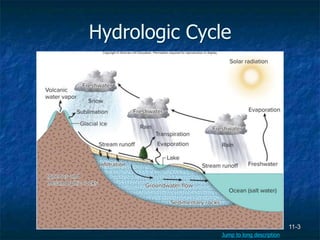

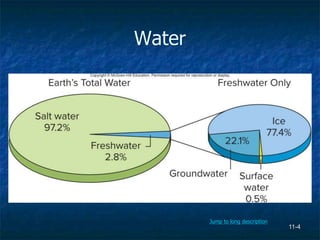

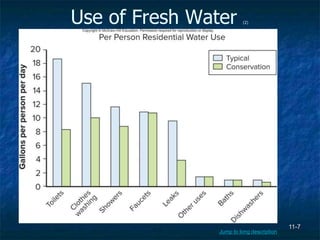

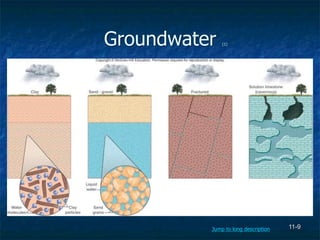

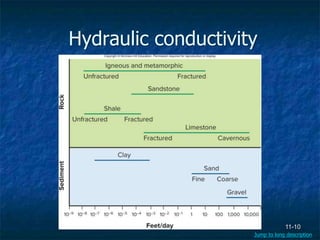

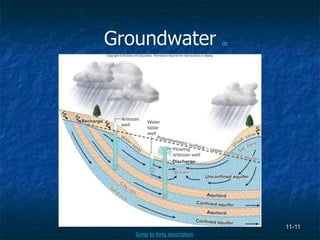

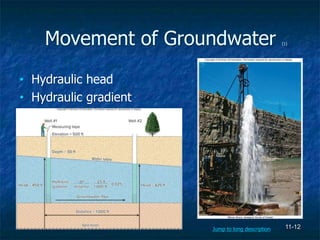

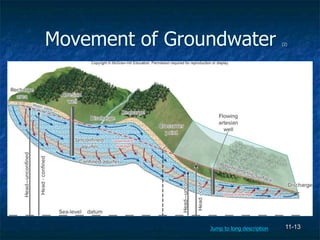

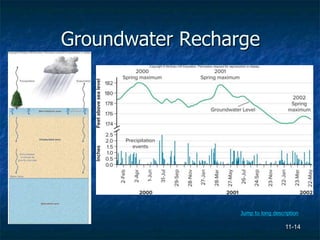

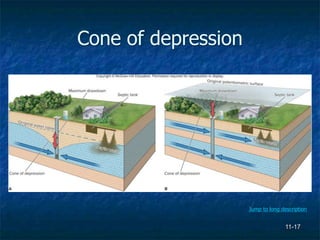

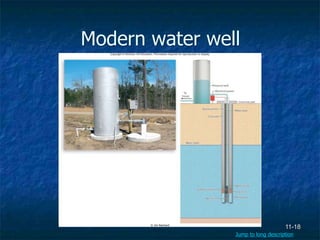

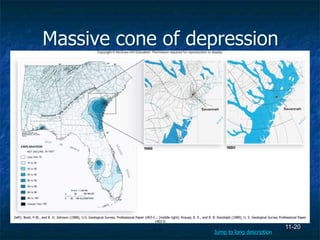

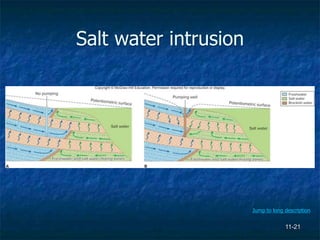

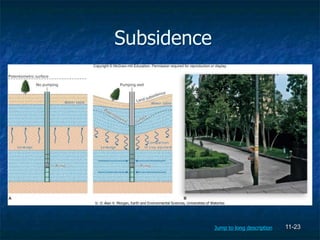

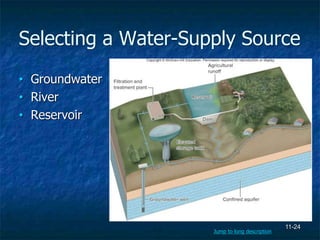

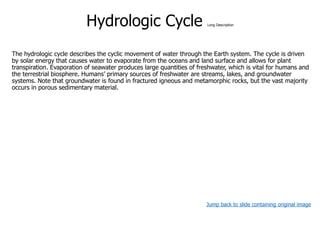

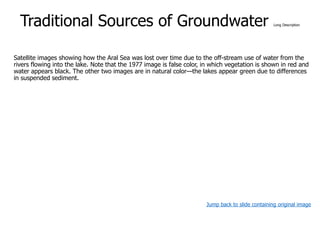

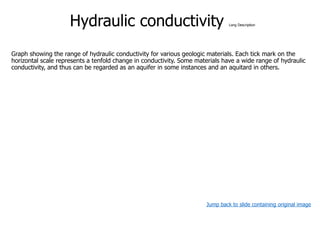

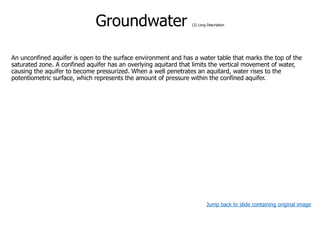

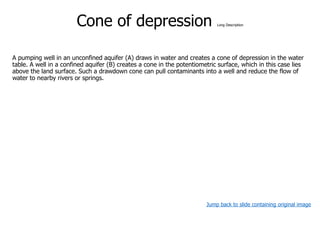

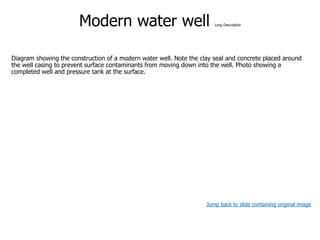

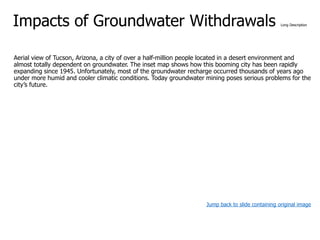

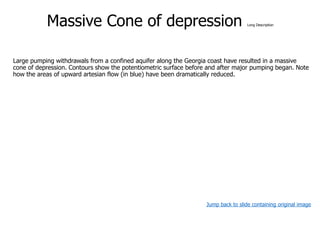

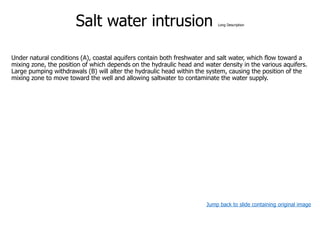

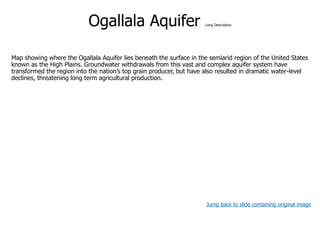

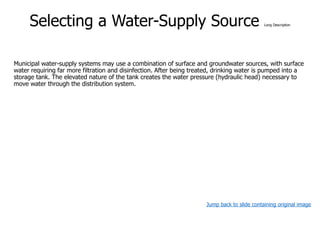

The document discusses water resources and groundwater. It describes the hydrologic cycle and sources of fresh water. It also discusses groundwater sources like aquifers and springs. Additionally, it covers topics like groundwater movement, recharge, and impacts of groundwater withdrawals like dry wells and land subsidence.