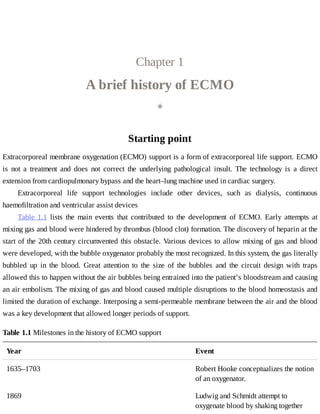

This document provides a brief history of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Early attempts at mixing gas and blood were hindered by blood clot formation until the discovery of heparin in the early 1900s. Various devices were then developed to mix gas and blood, including bubble oxygenators. The key development was interposing a semi-permeable membrane between the air and blood, allowing longer periods of support. Milestones included the first whole-body extracorporeal perfusion in 1929 and John Gibbon's successful use of cardiopulmonary bypass for open-heart surgery in 1953, laying the foundation for modern ECMO.