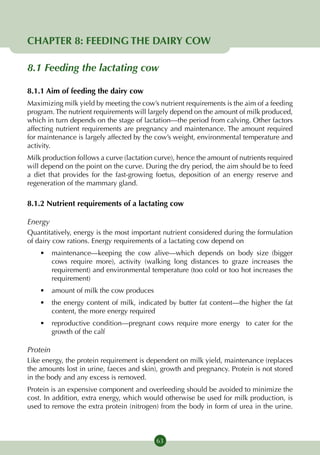

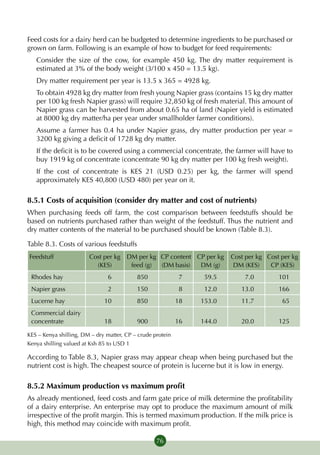

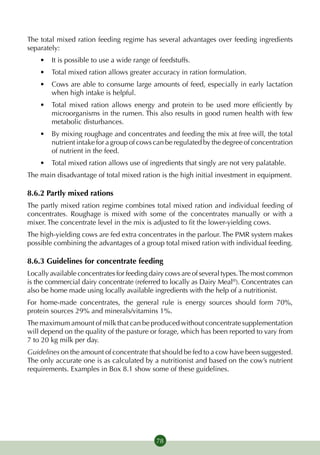

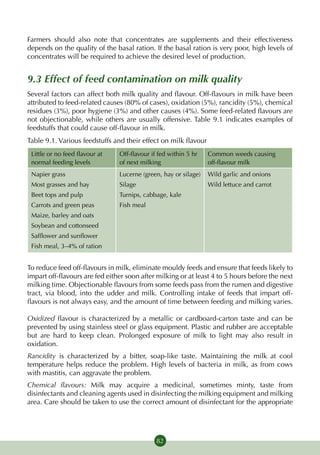

The document outlines the 'Feeding Dairy Cattle in East Africa' manual, produced by the East Africa Dairy Development Project to assist smallholder farmers in Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda in improving milk production and marketing. It emphasizes the importance of effective feeding practices, presents detailed nutritional guidelines, and explains various dairy production systems. The manual aims to empower farmers with accessible information to increase profitability and combat poverty in the region.

![Advantages

• It is cheaper than the intensive system.

• It is not labour intensive.

Disadvantages

• It requires dedicating much more land to grazing.

• Cows waste a lot of energy by walking while grazing in the field.

• It is difficult to accumulate manure for improving soil fertility in crop fields.

Natural grasses can be improved by oversowing with herbaceous legumes (e.g. Trifolium)

or planting grasses (e.g. Rhodes grass). Oversowing is the method of choice.

3.1.3 Semi-intensive system

In the semi-intensive system, the cattle graze for some time during the day and in the

afternoon or evening they are supplemented with other forages like Napier grass. This

method is a compromise between intensive and extensive systems, whereby land is not

limiting as in the intensive system but on the other hand is not enough to allow free

grazing throughout the day.

Due to population pressure leading to subdivision of land, this system tends towards the

intensive system.

3.1.4 Other systems

Other methods include ‘roadside grazing’ and ‘tethering’. Roadside grazing involves

herding cattle on the roadside where they graze on natural unimproved pastures. It is

popular in areas with land shortage. Tethering restricts the cow to a grazing area by

tying it with a rope to a peg. This can also be done on the roadside or any other public

land. However, in either of these systems the animals may not get enough to satisfy their

requirements.

3.2 Pasture management

Efficient pasture management results in high yields of good-quality pasture that can be

fed to dairy cattle for high milk production. Key activities to be considered include weed

control, grazing management and fertility management.

3.2.1 Weed control

Weeds can reduce the productivity of the sown pastures, particularly during the

establishment year, and should be controlled during the first year by either hand weeding

or using herbicide (2-4D amine at the rate of 2.5 litres per hectare [ha]). In subsequent

years fields are kept clean by slashing, hand pulling or mowing the weeds.

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eadddairymanual19032012-130122045223-phpapp02/85/Eadd-dairy-manual-19032012-28-320.jpg)