This document provides an overview of dairy herd management principles and practices. It discusses the importance of nutrition, cow comfort, and reproduction to dairy cow health and productivity. Facilities, expertise, and animal care are identified as fundamental factors that determine herd health. The dairy cow's life cycle is also summarized, outlining key stages from birth through calving and identifying management practices at each stage like colostrum feeding and nutritional management that are important for health and productivity.

![A guide to dairy herd management 43

• ‘Bob’ space – Can the cow ‘bob’ her muz-

zle at end of lunge?

• Rising room – Can the cow rise without

hitting the neck rail?

• Surface moisture – Is the bedding dry?

Indices used to assess free-stall use include:

• Stall use index (SUI) = [(# cows lying

in stalls) / (# cows not eating)]*100

(Recommended >75% following morning

milking)

• Stall standing index (SSI) = [# cows

standing or perching in stalls / all cows in

stalls]*100 (Recommended <20% 2 hours

after morning milking)

• Cow comfort index (CCI) = [(# cows lying

in stalls) / (# cows lying + # cows standing

in a stall)]*100 (Recommended 80–85%,

2 hours following morning milking)

Examining different facilities and enlisting the

services of a professional dairy designer is

recommended to avoid costly mistakes.

The design and dimensions of free-stalls is

important to achieve good cow comfort and

function. The concept of free-stalls is to pro-

vide a comfortable place for cows to lay and

at the same time control the position of the

cow so that urine and faeces does not con-

taminate the bedding material which the cow

lies on.

The dimensions of the free-stalls are impor-

tant as cows will be reluctant to lie down if it

is difficult to get into or out of the free-stalls.

Comfortable bedding material is also impor-

tant. A test is to drop from a standing position

onto your knees ('knee test'). If this can be

done comfortably, the beds are soft enough.

The recommended dimensions of free-stalls

takes into consideration the size of the cows

to be housed. Note that the dimensions in the

figure and table are for specific classes and

weights of cattle of Holsteins. Cows provide

feedback about the adequacy of their facilities

through their behaviour and by diseases and

injuries they may sustain.

Cows in confinement facilities should be

observed for the following evaluations:

• Surface cushion – Does the surface pass

the ‘knee test’ and supply traction?

• Body resting space – Is there adequate

space for resting body?

• Lunge space – Can the cow successfully

‘lunge’ to the front or side?

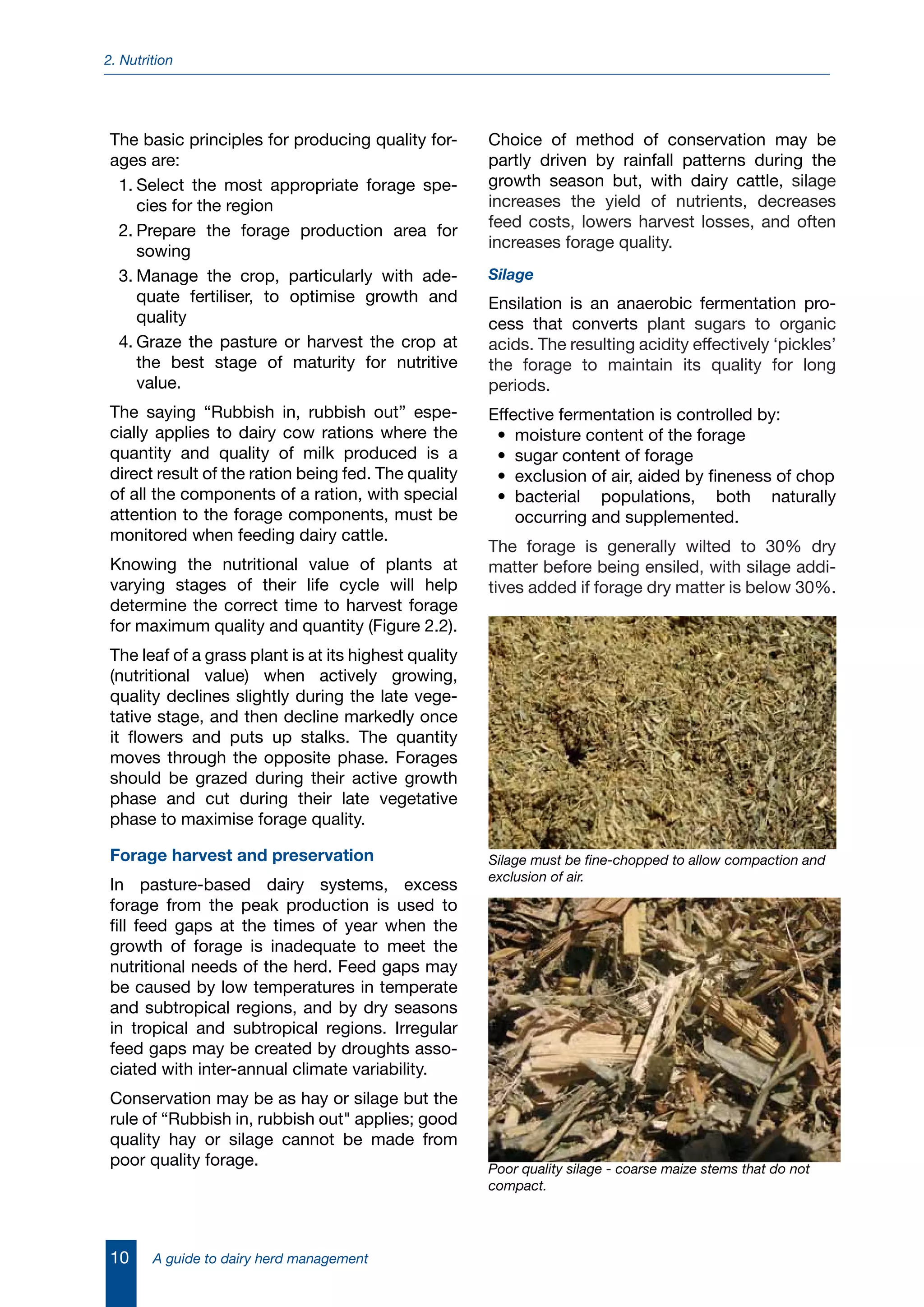

The cows on the left are standing half in and half out

of the bed. This ‘perching’ indicates a problem related

to the bedding softness as cows on the right are lying

down on newly laid rice hulls. Free-stalls should be

topped up with bedding twice a week and raked daily

to keep the bedding material soft and dry.

The cubicles can be arranged with cows facing one another (head-to-head), head-to-side wall, or tail-to-tail.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aguidetodairyherdmanagementaustralia-150929225635-lva1-app6892/75/A-guide-to-dairy-herd-management-australia-48-2048.jpg)