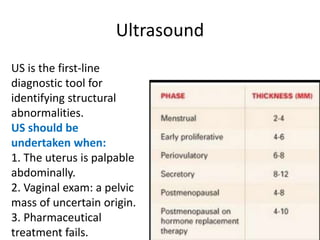

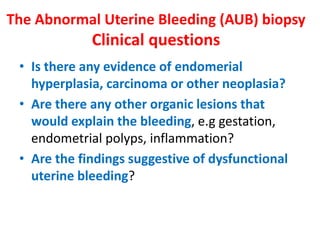

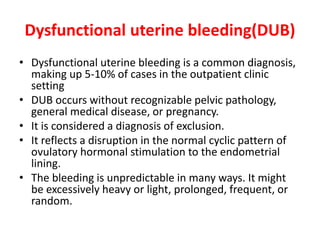

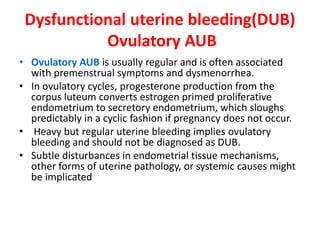

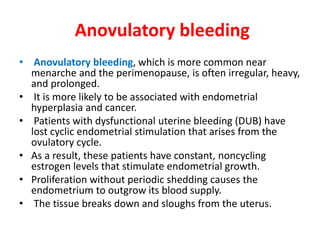

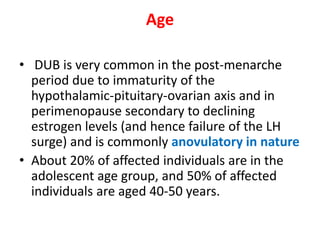

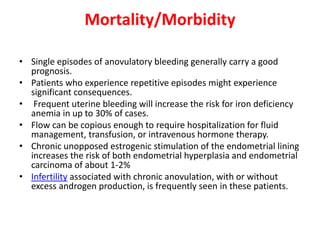

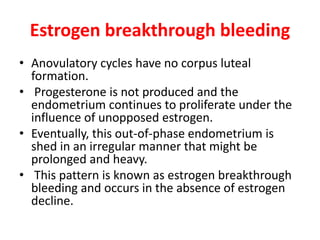

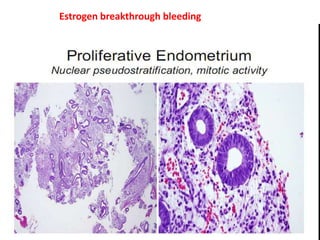

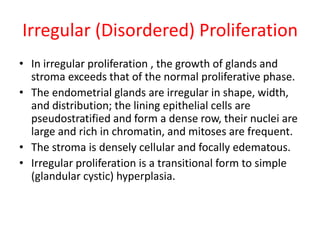

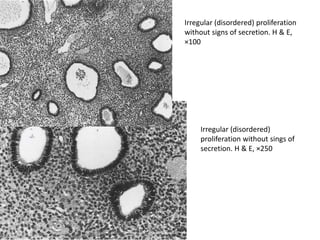

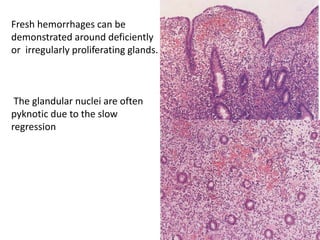

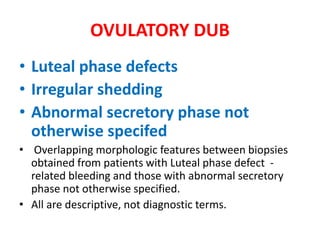

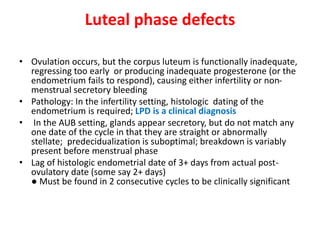

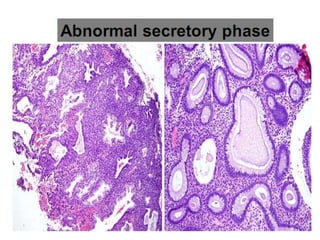

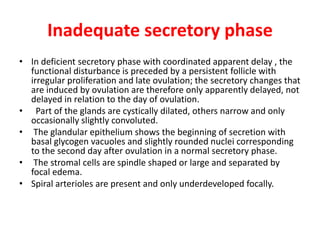

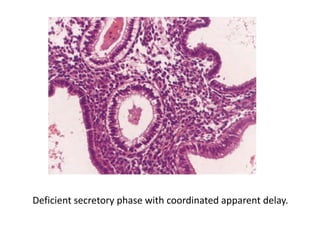

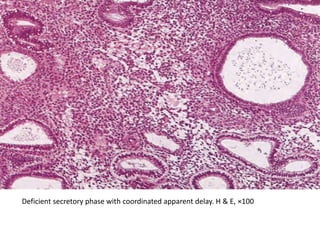

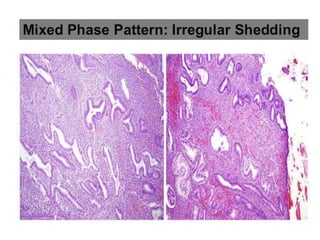

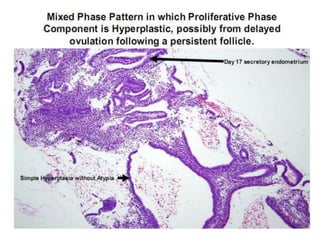

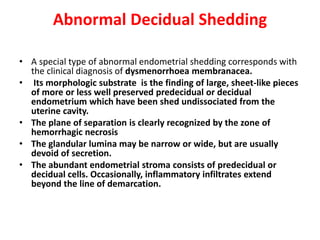

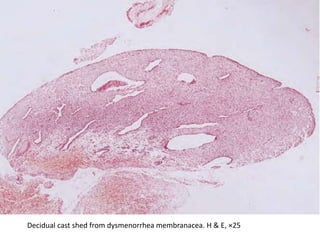

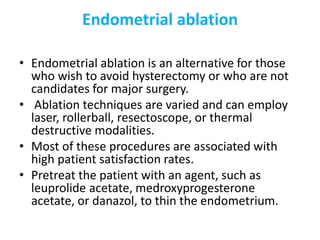

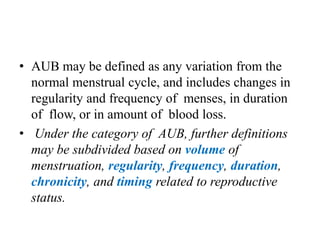

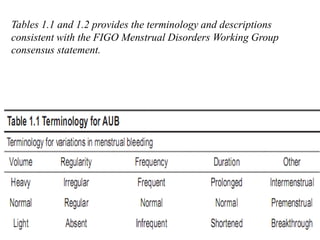

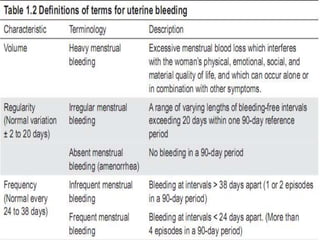

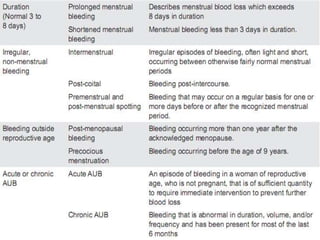

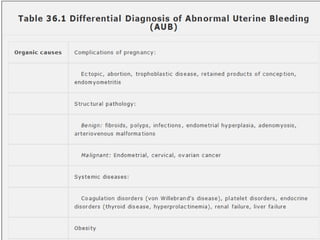

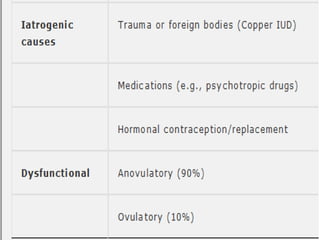

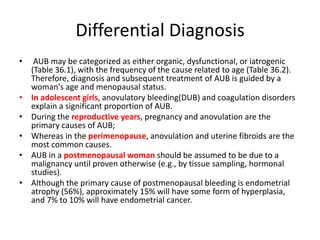

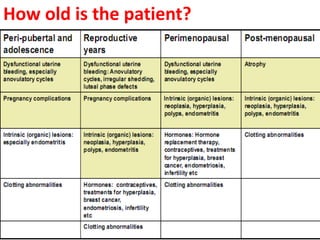

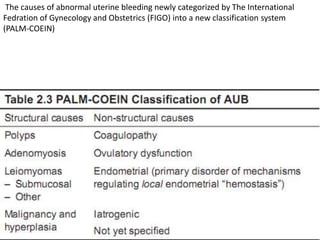

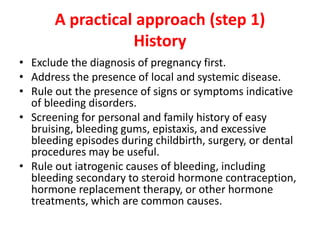

This document provides guidance on evaluating abnormal uterine bleeding through history, physical exam, laboratory tests, and imaging. It discusses evaluating for pregnancy, medical illnesses, bleeding disorders, and iatrogenic causes. Differential diagnoses are categorized as organic, dysfunctional, or iatrogenic. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding is considered a diagnosis of exclusion and can be ovulatory or anovulatory. Histopathological findings are described for conditions like irregular proliferation, luteal phase defects, and decidual shedding. Treatment aims and differential diagnoses are discussed based on a patient's age and menopausal status.

![A practical approach (step2)

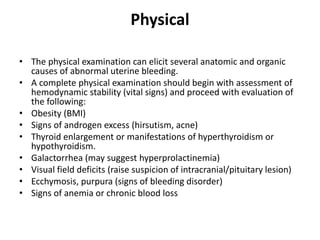

Physical examination

• General: obesity {(body mass index (BMI)]?

thyroid? Pallor ? pulse? Cachexia ?

• Abdomen: palpable mass?

• Pelvis: cervical or vaginal lesion?

• Bimanual exam: uterine size

• Speculum :cervical lesion

• PR: rectum or parametrium](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dub-150803204132-lva1-app6892/85/DUB-13-320.jpg)