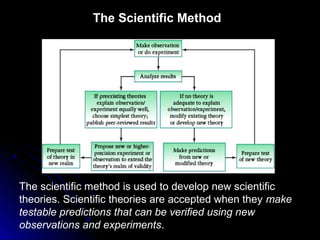

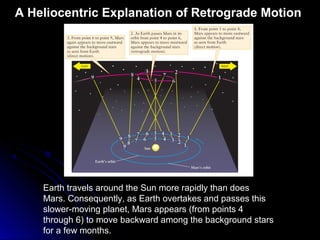

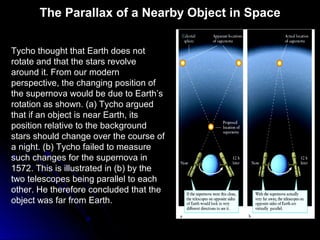

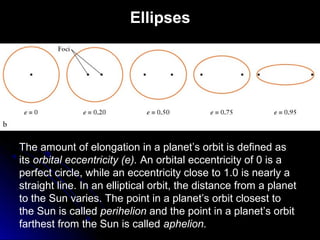

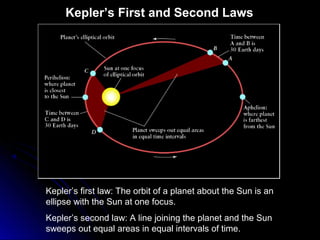

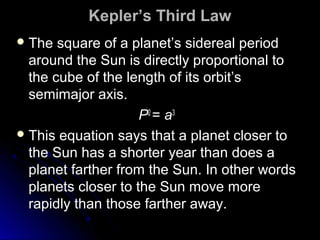

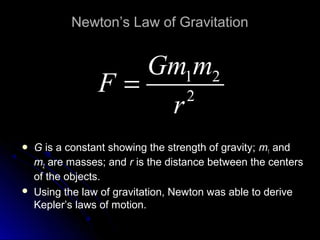

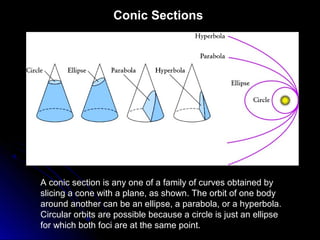

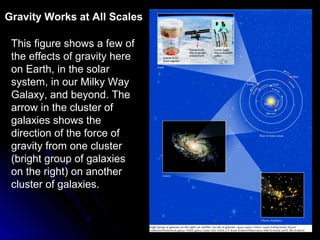

This chapter discusses the scientific discoveries that revealed the Earth is not at the center of the universe, including Copernicus's argument that planets orbit the Sun. It describes how Kepler determined planetary orbits depend on Tycho Brahe's observations, and how Newton formulated the law of gravity to explain why planets remain in orbit. The scientific method is used to develop theories through observation, hypothesis, prediction, testing, modification and simplification.