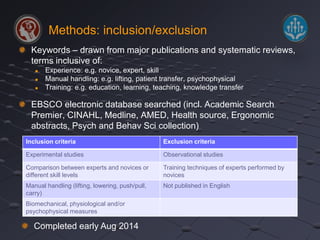

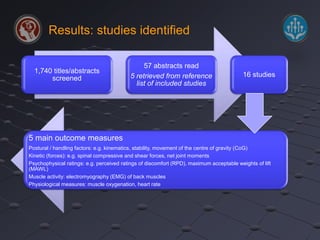

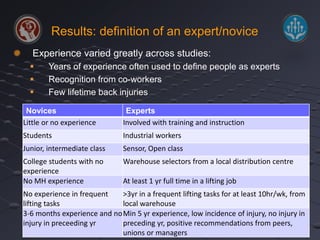

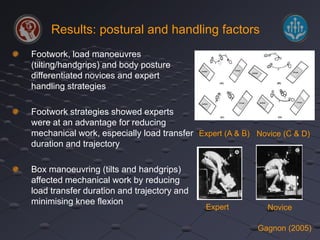

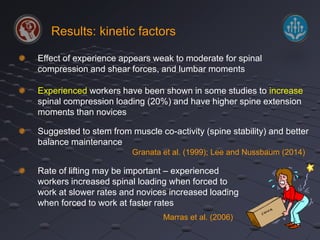

The document reviews literature on the differences in manual materials handling techniques between experienced workers and novices, with a focus on the implications for training. It highlights that existing training programs have shown limited success in reducing low back injuries and emphasizes the importance of understanding expert techniques and adapting training methods accordingly. The findings indicate that effective training should consider individual and workplace factors, as well as the realistic context of manual handling tasks.