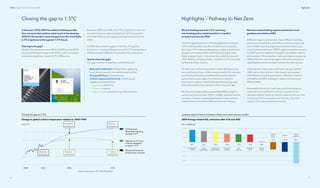

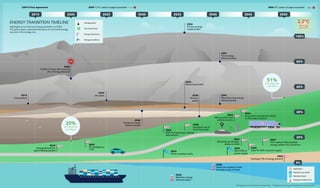

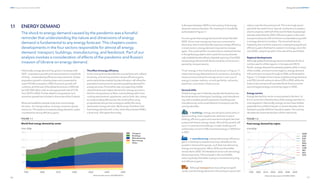

The document provides an overview and highlights from DNV's Energy Transition Outlook 2022 report. It summarizes that high energy prices and security concerns due to the war in Ukraine will not slow the long-term energy transition, though some short-term impacts are expected. Electricity remains the main driver of the transition and will more than double by 2050 as renewables like solar and wind grow rapidly. However, the report finds that global efforts have fallen short of the urgent action needed to limit warming to 1.5°C, and additional policies and measures are required to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.