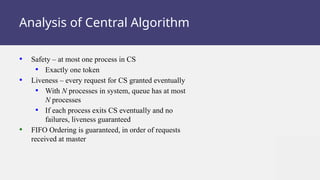

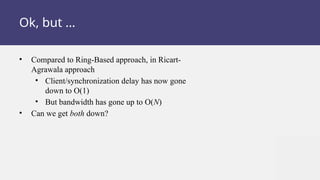

The document discusses mutual exclusion in distributed systems, emphasizing the need for controlled access to critical sections of code to prevent issues like data corruption encountered in concurrent transactions, such as banking transactions. It outlines various algorithms to achieve mutual exclusion, including centralized, ring-based, Ricart-Agrawala, and Maekawa's algorithms, highlighting their various performance metrics such as bandwidth and client delay. Additionally, the document mentions fault tolerance and the use of advisory locks in systems like Google's Chubby service.