This document is the third edition of Everett Rogers' book Diffusion of Innovations. It provides an overview of diffusion research from the early 1900s to the 1980s, summarizing key findings and theories. The book also critiques past diffusion research and proposes directions for future research. With over 3,000 publications on diffusion, it is one of the most widely researched topics in behavioral science. This edition aims to both continue and advance the theoretical framework for understanding the diffusion of new ideas and technologies.

![xvi Preface Preface xvii

this research field and its applications as the "diffusion of innova- reflects a much more critical stance. During the past twenty years or

tions." By choosing a title somewhat different from my second book, so, diffusion research has grown to be widely recognized, applied, and

I can help avoid confusion of these two volumes. admired, but it has also been subjected to constructive and destructive

Most diffusion studies prior to 1962 were conducted in the United criticism. This criticism is due in large part to the stereotyped and

States and Europe. In the period between the first and second editions limited ways in which most diffusion scholars have come to define the

of my diffusion book, during the 1960s, an explosion occurred in the scope and method of their field of study. Once diffusion researchers

number of diffusion investigations that were conducted in the devel- came to represent an "invisible college,"* they began to limit unnec-

oping nations of Latin America, Africa, and Asia. It was realized that essarily the ways in which they went about studying the diffusion of

the classical diffusion model could be usefully applied to the process innovations. Such standardization of approaches has, especially in the

of socioeconomic development. In fact, the diffusion approach was a past decade, begun to constrain the intellectual progress of diffusion

natural framework in which to evaluate the impact of development research.

programs in agriculture, family planning, public health, and nutri- Perhaps the diffusion case is rather similar to that of persuasion

tion. But in studying the diffusion of innovations in developing na- research, another important sub field of communication research.

tions, we gradually realized that certain limitations existed in the dif- Two of the leading persuasion scholars, Professors Gerald R. Miller

fusion framework. In some cases, development programs outran the and Michael Burgoon (1978, p. 31), recently described the myopic

diffusion model on which they were originally based. One intellectual view of the social-influence process held by most persuasion scholars:

outcome was certain modifications that have been made in the classi- "Students of persuasion may have fallen captive to the limits imposed

cal diffusion model. As a result, the diffusion paradigm that is by their own operational definitions of the area" [sentence was itali-

presented in this book is less culture-bound than in my previous cized in the original]. This self-criticism applies to diffusion re-

books. And the study of diffusion has today become worldwide. searchers as well, because, in fact, many diffusion scholars have con-

During the 1970s, I have also seen important changes, modifica- ceptualized the diffusion process as one-way persuasion. As such,

tions, and improvements made in the diffusion model in the United they also may be subject to the four shortcomings of persuasion

States and other industrialized nations. One important type of change research listed by Miller and Burgoon (1978, pp. 31-35):

has been to view the diffusion process in a wider scope and to under- 1. Persuasion (and diffusion) are seen as a linear, unidirectional

stand that diffusion is one part of a larger process which begins with a communication activity. An active source constructs messages in

perceived problem or need, through research and development on a order to influence the attitudes and/or behaviors of passive receivers.

possible solution, the decision by a change agency that this innovation Cause resides in the source, and effect in the receiver.

should be diffused, and then its diffusion (leading to certain conse- 2. Persuasion (and diffusion) are considered as a one-to-many

quences). Such a broader view of the innovation-development process communication activity. This view is inconsistent with more recent

recognizes that many decisions and activities must happen before the conceptions of persuasion: "Persuasion is not something one person

beginning of the diffusion of an innovation; often diffusion cannot be does to another but something he or she does with another" (Rear-

very completely understood if these previous phases of the total proc- don, 1981, p. 25).

ess are ignored. Chapter 4 of the present book deals with this issue of 3. Persuasion (and diffusion) scholars are preoccupied with an

where innovations come from, and how their origins affect their diffu- action-centered and issue-centered communication activity, such as

sion. selling products, actions, or policies. Largely ignored is the fact that

Another important intellectual change of the past decade, re- an important part of persuasion/diffusion is selling oneself and, per-

flected in Chapter 10, is the greatly increased interest in the innovation haps, other persons. It should be realized that one objective of certain

process in organizations. Such organizational decisions are different diffusion activities is to enhance one's personal credibility in the eyes

in important ways from innovation decisions by individuals, we now of others (as we detail in Chapters 8 and 9).

realize. *An invisible college is an informal network of researchers who form around an intel-

The present book also differs from its two predecessors in that it lectual paradigm to study a common topic (Price, 1963; Kuhn, 1970; Crane, 1972).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/diffusionofinnovations3rded-121130093410-phpapp02/85/Diffusion-of-innovations-3rd-ed-8-320.jpg)

![88

Diffusion of Innovations Contributions and Criticisms of Diffusion Research 89

standing of human behavior change and at the level of practice and of academic scholars since the Fliegel and Kivlin assessment: for ex-

policy. ample, said one study, "Innovation has emerged over the last decade

as possibly the most fashionable of social science areas" (Downs and

Mohr, 1976). A variety of behavioral science disciplines are involved

The Contributions and Status of Diffusion in the study of innovation. Said the same study, "This popularity is

not surprising. The investigations by innovation research of the salient

Research Today behavior of individuals, organizations, and political parties can have

significant social consequences. [These studies] imbue even the most

The status of diffusion research today is impressive. During the 1960s obscure piece of research with generalizability that has become rare as

and 1970s, the results of diffusion research have been incorporated in social science becomes increasingly specialized" (Downs and Mohr,

basic textbooks in social psychology, communication, public rela- 1976).

tions, advertising, marketing, consumer behavior, rural sociology, What is the appeal of diffusion research to scholars, to sponsors of

and other fields. Both practitioners (like change agents) and theoreti- such research, and to students, practitioners, and policy-makers who

cians have come to regard the diffusion of innovations as a useful field use the results of diffusion research? Why has so much diffusion

of social science knowledge. Many U.S. government agencies have a literature been produced?

division devoted to diffusing technological innovations to the public 1. The diffusion model is a conceptual paradigm with relevance

or to local governments; examples are the U.S. Department of Trans- for many disciplines. The multidisciplinary nature of diffusion re-

portation, the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of search cuts across various scientific fields; a diffusion approach pro-

Agriculture, and the U.S. Department of Education. These same vides a common conceptual ground that bridges these divergent disci-

federal agencies also sponsor research on diffusion, as does the Na- plines and methodologies. There are few disciplinary limits on who

tional Science Foundation and a number of private foundations. We studies innovation. Most social scientists are interested in social

have previously discussed the applications of diffusion approaches in change; diffusion research offers a particularly useful means to gain

agricultural development and family planning programs in Latin such understandings because innovations are a type of communica-

America, Africa, and Asia. Further, most commercial companies tion message whose effects are relatively easy to isolate. Perhaps there

have a marketing department that is responsible for diffusing new is a parallel to the use of radioactive tracers in studying the process of

products and a market research activity that conducts diffusion inves- plant growth. One can understand social change processes more accu-

tigations in order to aid the company's marketing efforts. Because in- rately if the spread of a new idea is followed over time as it courses

novation is occurring throughout modern society, the applications of through the structure of a social system. Because of their salience, in-

diffusion theory and research are found in many places. novations usually leave deep scratches on individual minds, thus

Diffusion research, thus, has achieved a prominent position to- aiding respondents' recall ability. The foreground of scientific interest

day. Such has not always been the case. Some years ago, two members thus stands out distinctly from background "noise." The process of

of the diffusion research fraternity, Fliegel and Kivlin (1966b), com- behavior change is illuminated in a way that is distinctive to the diffu-

plained that this field had not yet received its deserved attention from sion research approach, especially in terms of the role of concepts like

students of social change: "Diffusion of innovation has the status of a information and uncertainty. The focus of diffusion research on trac-

bastard child with respect to the parent interests in social and cultural ing the spread of an innovation through a system in time and/or in

change: Too big to ignore but unlikely to be given full recognition." * , space has the unique quality of giving "life" to a behavioral change

The status of diffusion research has improved considerably in the eyes process. A conceptual and analytical strength is gained by incor-

porating time as an essential element in the analysis of human behav-

ior change.

* Their impression was most directly based upon the writings of La Piere (1965) and

Moore (1963, pp. 85-88). Diffusion research offers something of value to each of the social](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/diffusionofinnovations3rded-121130093410-phpapp02/85/Diffusion-of-innovations-3rd-ed-54-320.jpg)

![90 Diffusion of Innovations Contributions and Criticisms of Diffusion Research 91

science disciplines. Economists are centrally interested in growth; vidual innovativeness through cross-sectional analysis of survey data.

technological innovation is one means to foster the rate of economic Although the methodological straightforwardness of such diffusion

growth in a society. The degree of diffusion of a technological innova- studies encouraged the undertaking of many such investigations, it

tion is often used as an important indicator of socioeconomic develop- also may have restricted their theoretic advance.

ment by scholars of development. Students of organization are con-

cerned with processes and patterns of change in and between formal

institutions, and in how organizational structure is altered by the in-

troduction of a new technology. Social psychologists try to under- Criticisms of Diffusion Research

stand the sources and causes of human behavior change, especially as

such individual change is influenced by groups and networks to which Although diffusion research has made numerous important contribu-

the individual belongs. Sociologists and anthropologists share an tions to our understanding of human behavior change, its potential

academic interest in social change, although they usually attack the would have been even greater had it not been characterized by such

study of change with different methodological tools. The exchange of shortcomings and biases as those discussed in this section. If the 1940s

information in order to reduce uncertainty is central to communica- marked the original formulation of the diffusion paradigm, the 1950s

tion research. So the diffusion of innovations is of note to each of the were a time of proliferation of diffusion studies in the United States,

social sciences. the 1960s involved the expansion of such research in developing na-

2. The apparent pragmatic appeal of diffusion research in solving tions, and the 1970s have been the era of introspective criticism for

problems of research utilization is high. The diffusion approach seems diffusion research. Until the past decade, almost nothing of a critical

to promise a means to provide solutions (1) to individuals and/or or- nature was written about this field; such absence of critical viewpoints

ganizations who have invested in research on some topic and seek to may have indeed been the greatest weakness of all of diffusion re-

get it utilized, and/or (2) those who desire to use the research results of search.

others to solve a particular social problem or fulfill a need. This prom- Every field of scientific research makes certain simplifying as-

ise has attracted many researchers to the diffusion arena even though sumptions about the complex reality that it studies. Such assumptions

fulfillment of this potential has yet to be fully proven in practice. The are built into the intellectual paradigm that guides the scientific field.

diffusion approach helps connect research-based innovations and the Often these assumptions are not recognized, even as they affect such

potential users of such innovations. important matters as what is studied and what ignored, and which

3. The diffusion paradigm allows scholars to repackage their em- research methods are favored and which rejected. So when a scientist

pirical findings in the form of higher-level generalizations of a more follows a theoretical paradigm, he or she puts on a set of intellectual

theoretical nature. Such an orderly procedure in the growth of the dif- blinders that help the researcher to avoid seeing much of reality.' 'The

fusion research field has allowed it to progress in the direction of a prejudice of [research] training is always a certain 'trained

gradual accumulation of empirical evidence. Were it not for the gen- incapacity': the more we know about how to do something, the harder

eral directions for research activities provided by the diffusion it is to learn to do it differently" (Kaplan, 1964, p. 31). Such "trained

paradigm, the impressive amount of research attention given to study- incapacity" is, to a certain extent, necessary; without it, a scientist

ing diffusion would not amount to much. Without the diffusion could not cope with the vast uncertainties of the research process in his

model, this huge body of completed research would just be "a mile field. Every research worker, and every field of science, has many

wide and an inch deep." blind spots.

4. The research methodology implied by the classical diffusion The growth and development of a research field is a gradual puz-

model is clear-cut and relatively facile. The data are not especially dif- zle-solving process by which important research questions are iden-

ficult to gather; the methods of data analysis are well laid out. Diffu- tified and eventually answered. The progress of a scientific field is

sion scholars have focused especially on characteristics related to indi- helped by realization of its assumptions, biases, and weaknesses. Such](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/diffusionofinnovations3rded-121130093410-phpapp02/85/Diffusion-of-innovations-3rd-ed-55-320.jpg)

![98 Diffusion of Innovations Contributions and Criticisms of Diffusion Research 99

ing unit's situation. As we show in Chapter 5, for the first thirty-five to investigate. Some adopters may not be able to tell a researcher why

years or so of diffusion research, we simply did not recognize that re- they decided to use a new idea. Other adopters may be unwilling to do

invention existed. An innovation was regarded by diffusion scholars so. Seldom are simple, direct questions in a survey interview adequate

as an invariant during its diffusion process. Now we realize, belatedly, to uncover an adopter's reasons for using an innovation. But we

that an innovation may be perceived somewhat differently by each should not give up on trying to find out the "why" of adoption just

adopter and modified to suit the individual's particular situation. because valuable data about adoption motivations are difficult to ob-

Thus, diffusion scholars no longer assume that an innovation is ''per- tain by the usual methods of diffusion research data gathering.

fect" for all potential adopters in solving their problems and meeting It is often assumed that an economic motivation is the main thrust

their needs. for adopting an innovation, especially if the new idea is expensive.

4. Researchers should investigate the broader context in which an Economic factors are undoubtedly very important for certain types of

innovation diffuses, such as how the initial decision is made that the innovations and their adopters, such as the use of agricultural innova-

innovation should be diffused to members of a system, how public tions by U.S. farmers. But the prestige secured from adopting an in-

policies affect the rate of diffusion, how the innovation of study is novation before most of one's peers may also be important. For in-

related to other innovations and to the existing practice(s) that it stance, Becker (1970a, 1970b) found that prestige motives were very

replaces, and how it was decided to conduct the R&D that led to the important for county health departments in deciding to launch new

innovation in the first place (Figure 3-5). This wider scope to diffu- health programs. A desire to gain social prestige was also found to be

sion studies helps illuminate the broader system in which the diffusion important by Mohr (1969) in his investigation of the adoption of tech-

process occurs. As explained in Chapter 4, there is much more to dif- nological innovations by health organizations. Mohr explained that

fusion than just variables narrowly related to an innovation's rate of "a great deal of innovation in [health] organizations, especially large

adoption. or successful ones, is 'slack' innovation. After solution of immediate

5. We should increase our understanding of the motivations for problems, the quest for prestige rather than the quest for organiza-

adopting an innovation. Strangely, such "why" questions about tional effectiveness or corporate profit motivates the adoption of

adopting an innovation have only seldom been probed by diffusion re- most new programs and technologies." Perhaps prestige motivations

searchers; undoubtedly, motivations for adoption are a difficult issue are less important and profit considerations are paramount in private

organizations, unlike the public organizations studied by Becker and

Mohr. But we simply do not know because so few diffusion research-

ers have tried to assess motivations for adoption.

I believe that if diffusion scholars could more adequately see an in-

novation through the eyes of their respondents, including a better un-

derstanding of why the innovation was adopted, the diffusion re-

searchers would be in a better position to shed their pro-innovation

bias of the past. A pro-innovation tilt is dangerous in that it may cloud

the real variance in adopters' perceptions of an innovation. An astute

observer of diffusion research, Dr. J. D. Eveland (1979), stated:

"There is nothing inherently wrong with ... a pro-innovation value

system. Many innovations currently on the market are good ideas in

terms of almost any value system, and encouraging their spread can be

viewed as virtually a public duty." But even in the case of an over-

whelmingly advantageous innovation, a researcher should not forget

that the various individuals in the potential audience for an innova-

tion may perceive it in light of many possible sets of values. If the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/diffusionofinnovations3rded-121130093410-phpapp02/85/Diffusion-of-innovations-3rd-ed-59-320.jpg)

![106 Diffusion of Innovations Contributions and Criticisms of Diffusion Research 107

old age. Instead of seeking a system-blame solution, by creating public mendations to use an innovation. They attribute such an improper

programs like agricultural mechanization and a social security system response to the explanation that these individuals are traditionally

to substitute for large families, government officials criticized parents resistant to change, and/or "irrational." In some cases, a more

for not adopting contraceptives and for having "too many" children. careful analysis showed that the innovation was not as appropriate for

Such an individual-blame strategy for solving the overpopulation later adopters, perhaps because of their smaller-sized operations and

problem has not been very successful in most developing nations, ex- more limited resources. Indeed they may have been extremely rational

cept in certain countries where rapid socioeconomic development has in not adopting (if rationality is defined as use of the most effective

changed the system-level reasons for having large families (Rogers, means to reach a given goal). In this case, an approach with more em-

1973). phasis on system-blame might question whether the R&D source of in-

In each of these five illustrations, a social problem was initially novations was properly tuned to the actual needs and problems of the

defined in terms of individual-blame. The resulting diffusion program later adopters in the system, and whether the change agency, in recom-

to change human behavior was not very successful until, in some mending the innovation, was fully informed about the actual life

cases, system-blame factors were also recognized. These five cases situation of the later adopters.

suggest that we frequently make the mistake of defining social prob- In fact, a stereotype of later adopters by change agents and others

lems solely in terms of individual-blame. as traditional, uneducated, and/or resistant to change may become a

self-fulfilling prophecy. Change agents do not contact the later

adopters in their system because they feel, on the basis of their

INDIVIDUAL-BLAME AND THE DIFFUSION OF INNOVATIONS stereotypic image, that such contact will not lead to adoption. The

eventual result, obviously, is that without the information inputs and

"The variables used in diffusion models [to predict innovativeness], other assistance from the change agents, the later adopters are even

then, are conceptualized so as to indicate the success or failure of the less likely to adopt. Thus, the individual-blame image of the later

individual within the system rather than as indications of success or adopters fulfills itself. Person-blame interpretations are often in

failure of the system" (Havens, 1975, p. 107, emphasis in original). everybody's interest except those who are subjected to individual-

Examples of such individual-blame variables that have been cor- blame.

related with individual innovativeness in past diffusion investigations

include formal education, size of operation, income, cosmopolite-

ness, and mass media exposure. In addition, these past studies of indi- REASONS FOR SYSTEM-BLAME

vidual innovativeness have included some predictor variables that

might be considered system-blame factors, like change agent contact It may be understandable (although regrettable) that change agents

with clients and the degree to which a change agency provides finan- fall into the mental trap of individual-blame thinking about why their

cial assistance (such as in the form of credit to purchase an clients do not adopt an innovation. But why and how does diffusion

innovation). But seldom is it implied in diffusion research publica- research also reflect such an individual-blame orientation?

tions that the source or the channel may be at fault for not providing 1. As we have implied previously, some diffusion researchers ac-

more adequate information, for promoting inappropriate innova- cept a definition of the problem that they are to study from the spon-

tions, or for failing to contact less-educated members of the audience sors of their research. And so if the research sponsor is a change

who may especially need the change agent's help. agency with an individual-blame bias, the diffusion scholar often

Late adopters and laggards are often most likely to be individually picks up an individual-blame orientation. The ensuing research may

blamed for not adopting an innovation and/or for being much later in then contribute, in turn, toward social policies of an individual-blame

adopting than the other members of their system. Change agents feel nature. "Such research frequently plays an integral role in a chain of

that such later adopters are not dutifully following the experts' recom- events that results in blaming people in difficult situations for their](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/diffusionofinnovations3rded-121130093410-phpapp02/85/Diffusion-of-innovations-3rd-ed-63-320.jpg)

![114 Diffusion of Innovations Contributions and Criticisms of Diffusion Research 115

There are more appropriate research designs for gathering data The pro-innovation bias in diffusion research, and the overwhelm-

about the time dimension in the diffusion process: (1) field ex- ing reliance on correlational analysis of survey data, often led in the

periments, (2) longitudinal panel studies, (3) use of archival records, past to avoiding or ignoring the issue of causality among the variables

and (4) case studies of the innovation process with data from multiple of study. We often speak of "independent" and "dependent" vari-

respondents (each of whom provides a validity check on the others' ables in diffusion research, having taken these terms from experi-

data). (We shall describe these case study approaches to the innova- mental design and then used them rather loosely with correlational

tion process in organizations in Chapter 10.) These methodologies analysis. A dependent variable usually means the main variable in

provide moving pictures, rather than still photos, of the diffusion which the investigator is interested; in about 60 percent of all diffusion

process, and thus reflect the time dimension more accurately. Unfor- researches, this dependent variable is innovativeness, as we showed in

tunately, these alternatives to the one-shot survey have not been Table 2-2. It is usually implied in diffusion research that the indepen-

widely used in past diffusion research. The last time that a tabulation dent variables "lead to" innovativeness, although it is often unstated

was made of the data-gathering designs used in diffusion research (in or unclear whether this really means that an independent variable

1968 when there were 1,084 empirical diffusion publications), about causes innovativeness.

88 percent of all diffusion researches were one-time surveys. About 6 In order for variable X to be the cause of variable Y, (1) X must

percent were longitudinal panel studies with data gathered at two or precede Y in time-order, (2) the two variables must be related, or co-

more points in time, and 6 percent were field experiments. Our im- vary, and (3) X must have a "forcing quality" on Y. Most diffusion

pression is that these proportions would be about the same today. The researches only determine that various independent variables co-vary

research design predominantly used in diffusion research, therefore, with innovativeness; correlational analysis of one-shot survey data

cannot tell us much about the process of diffusion over time, other does not allow the determination of time-order. Such correlational

than what can be reconstituted from respondents' recall data. studies face a particular problem of time-order that I call "yesterday's

innovativeness": in most diffusion surveys, innovativeness is mea-

sured as of "today" with recall data about past adoption behavior,

PROBLEMS IN DETERMINING CAUSALITY while the independent variables are measured in the present tense. It is

obviously impossible for an individual's attitudes or personal charac-

The problem here is not just that such recall data may not be perfectly teristics, formed and measured now, to have caused his adoption of an

accurate (they assuredly are not), but that the cross-sectional survey innovation three years or five years previously (this would amount to

data are unable to answer many of the "why" questions about diffu- X following Fin time-order, making it impossible for X to cause Y).

sion. The one-shot survey provides grist for description, of course, Here again we see the importance of research designs that allow us

and also enables cross-sectional correlational analysis: various in- to more clearly understand the over-time aspects of diffusion. Field

dependent variables are associated with a dependent variable, which is experiments are ideally suited to the purpose of assessing the effect of

usually innovativeness. But little can be learned from such a correla- various independent variables (the interventions or treatments) on a

tional analysis approach about why a particular independent variable dependent variable (like innovativeness). A field experiment is an ex-

covaries with innovativeness. periment conducted under realistic conditions (rather than in the

"Such factors (as wealth, size, cosmopoliteness, etc.) may be laboratory) in which preintervention and postintervention measure-

causes of innovation, or effects of innovativeness, or they may be in- ments are usually obtained by surveys. In the typical diffusion field ex-

volved with innovation in cycles of reciprocal causality through time, periment, the intervention is some communication strategy to speed

or both they and the adoption of new ideas may be caused by an out- up the diffusion of an innovation. For example, the diffusion inter-

side factor not considered in a given study" (Mohr, 1966, p. 20). vention may be an incentive payment for adopting family planning

Future diffusion research must be designed so as to probe the time- that is offered in one village and not in another (Rogers, 1973, pp.

.ordered linkages among the independent and dependent variables. 215-217). "The best way to understand any dynamic process [like dif-

And one-shot surveys can't tell us much about time-order, or about fusion] is to intervene in it, and to see what happens" (Tornatzky et al,

the broader issue of causality. 1980, p. 17). Most past diffusion research has studied "what is,"](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/diffusionofinnovations3rded-121130093410-phpapp02/85/Diffusion-of-innovations-3rd-ed-67-320.jpg)

![176 177

Diffusion of Innovations The Innovation-Decision Process

invention of a new idea, it was considered as a very unusual kind of These researchers traced the adoption and implementation of the edu-

behavior, and was treated as "noise" in diffusion research. Adopters cational innovation of ''differentiated staffing" in four schools over a

were considered to be passive acceptors of innovations, rather than one-year period. They concluded that "differentiated staffing was lit-

active modifiers and adapters of new ideas. Once diffusion scholars tle more than a word for most participants [that is, teachers and

made the mental breakthrough of recognizing that re-invention could school administrators], lacking concrete parameters with respect to

happen, they began to find that quite a lot of it occurred, at least for the role performance of participants... .The word could (and did)

certain innovations. Naturally, re-invention could not really be in- mean widely differing things to the staff, and nothing to some....

vestigated until diffusion researchers began to gather data about im- The innovation was to be invented on the inside, not implemented

plementation, for most re-invention occurs at the implementation from the outside." These scholars noted the degree to which the inno-

stage of the innovation-decision process. In fact, the recent finding vation was shaped differently in each of the four organizations they

that a great deal of re-invention occurs for certain innovations sug- studied.*

gests that previous diffusion research, by measuring adoption as a When investigations are designed with the concept of re-invention

stated intention to adopt (at the decision stage), may have erred by in mind, a certain degree of re-invention is usually found. For in-

measuring innovation that did not actually occur in some cases, or at stance, previous research on innovation in organizations had assumed

least that did not occur in the way that was expected. The fact that re- that a new technological idea enters a system from external sources

invention may occur is a strong argument for measuring adoption at and then is adopted (with relatively little adaptation of the innovation)

the implementation stage, as change that has actually happened. As and implemented as part of the organization's ongoing operations.

action by the adopter, rather than as intention. The assumption is that adoption of an innovation by individual or

Most scholars in the past have made a distinction between inven- organization A will look much like adoption of this same innovation

tion and innovation. Invention is the process by which a new idea is by individual or organization B. Recent investigations call this

discovered or created, while adoption is a decision to make full use of assumption into serious question. For instance:

an innovation as the best course of action available. Thus, adoption is • A national survey of schools adopting educational innovations

the process of adopting an existing idea. This difference between in- promoted by the National Diffusion Network, a decentralized

vention and adoption, however, is not so clear-cut when we acknowl- diffusion system, found that 56 percent of the adopters imple-

edge that an innovation is not necessarily a fixed entity as it diffuses mented only selected aspects of an innovation; much such re-

within a social system. For this reason, "re-invention" seems like a invention was relatively minor, but 20 percent of the adoptions

rather appropriate word to describe the degree to which an innovation amounted to large changes in the innovation (Emrick et al, 1977,

is changed or modified by the user in the process of its adoption and

implementation.* pp. 116-119).

• An investigation of 111 innovations in scientific instruments by

von Hippel (1976) found that in about 80 percent of the cases, the

How MUCH RE-INVENTION OCCURS? innovation process was dominated by the user (that is, a

customer). The user might even build a prototype model of the

new product, and then turn it over to a manufacturer. So the

The recent focus on re-invention was launched by Charters and

"adopters" played a very important role in designing and rede-

Pellegrin (1972), who were the first scholars to recognize the occur-

rence of re-invention (although they did not use the term per se). signing these industrial innovations.

• Of the 104 adoptions of innovations by mental health agencies

that were studied in California, re-invention occurred somewhat

* At least re-invention is a more apt term than others proposed for this behavior, like

the anthropological concept of reinterpretation, the process in which the adopters of * Undoubtedly one reason why Charters and Pellegrin became aware of re-invention

an innovation use it in a different way and/or for different purposes than when it was was due (1) to their use of a process research approach rather than a variance research

invented or diffused to them. Although the idea of reinterpretation has been around approach (as explained later in this chapter), and (2) to their focus on the implementa-

for years, it has never caught on among diffusion scholars. tion stage in the innovation-decision process for differentiated staffing.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/diffusionofinnovations3rded-121130093410-phpapp02/85/Diffusion-of-innovations-3rd-ed-98-320.jpg)

![212

Diffusion of Innovations Attributes of Innovations and Their Rate of Adoption 213

phasized by Wasson (1960), who said that "The ease or difficulty of Nevertheless, an ideal research design would actually measure the

introduction [of ideas] depends basically on the nature of the 'new' in attributes of innovations at t1 in order to predict the rate of adoption

the new product—the new as the customer views the bundle of services for these innovations at t2 (Tornatzky and Klein, 1981). Unfortu-

he perceives in the newborn.'' It is the receivers' perceptions of the at- nately, the conventional repertoire of social science research methods

tributes of innovations, not the attributes as classified by experts or is generally ill suited to the task of gathering data on behavior in the

change agents, that affect their rate of adoption. Like beauty, innova- "here and now" to predict behavior in the "there and then." There is

tions exist only in the eye of the beholder. And it is the beholder's no perfect solution to this problem, but several research approaches

perceptions that influence the beholder`s behavior. are useful for helping predict into the future:

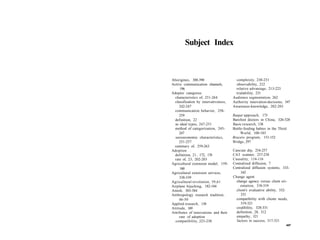

Although the first research on attributes of innovations and their

rate of adoption was conducted with farmers, several recent studies of 1. Extrapolation from the rate of adoption of past innovations

teachers and school administrators suggest that similar attributes may into the future for the other innovations.

be important in predicting the rate of adoption for educational in- 2. Describing a hypothetical innovation to its potential adopters,

novations. Holloway (1977) designed his research with one hundred and determine its perceived attributes, so as to predict its rate of

high school principals around the five attributes described in this adoption.

chapter. General support for the present framework was found, 3. Investigating the acceptability of an innovation in its prediffu-

although the distinction between relative advantage and compatibility sion stages, such as when it is just being test marketed and

was not very clear-cut, and the status-conferring aspects of educa- evaluated in trials.

tional innovations emerged as a sixth dimension predicting rate of None of these methods of studying the attributes of innovations is

adoption. Holloway (1977) factor-analyzed Likert-type scale items an ideal means for predicting the future rate of adoption of innova-

measuring his respondents' perceptions of new educational ideas to tions. But when they are used, especially in concert, they are better

derive his six attributes. The method of factor analysis has similarly than nothing. And in any event, research on predicting an

been used with data from teachers (Hahn, 1974; Clinton, 1973) and innovation's rate of adoption would be more valuable if data on the

from farmers (Elliott, 1968; Kivlin, 1960); the results vary somewhat attributes of the innovation were gathered prior to, or concurrently

from study to study, but the strongest support is generally found for with, individuals' decisions to adopt the innovation (Tornatzky and

the attribute dimensions of relative advantage, compatibility, and Klein, 1981, p. 5).*

complexity, with somewhat weaker support for the existence of

trialability and observability.

We conclude that the most important attributes of innovations for

most respondents can be subsumed under the five attributes that we Relative Advantage

use as our general framework.

The usefulnes of research on the attributes of innovations is Relative advantage is the degree to which an innovation is perceived as

mainly to predict their future rate of adoption. Most past research, being better than the idea it supersedes. The degree of relative advan-

however, has been postdiction instead of prediction. That is, the at- tage is often expressed in economic profitability, in status giving, or in

tributes of innovations are considered independent variables in ex- other ways. The nature of the innovation largely determines what

plaining variance in the dependent variable of rate of adoption of in- specific type of relative advantage (such as economic, social, and the

novations. The dependent variable is measured in the recent past, and like) is important to adopters, although the characteristics of the

the independent variables are measured in the present; so attributes potential adopters also affect which dimensions of relative advantage

are hardly predictors of the rate of adoption in past research. are most important (as we shall show in this section).

Generalizations, however, about such attributes as relative advantage

or compatibility to explain rate of adoption have been derived from *Just such a research approach was used by Ostlund (1974) who gathered

past research, and these generalizations can be used to predict the rate respondents' ratings on the perceived attributes of consumer innovations prior to

their introduction on the commercial market, in order to predict the new products'

of adoption for innovations in the future. rate of adoption.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/diffusionofinnovations3rded-121130093410-phpapp02/85/Diffusion-of-innovations-3rd-ed-116-320.jpg)

![214 215

Diffusion of Innovations Attributes of Innovations and Their Rate of Adoption

Economic Factors and Rate of Adoption the most important single predictor of rate of adoption. But to argue

that economic factors are the sole predictors of rate of adoption is

Some new products involve a series of successful technological im- ridiculous. Perhaps if Dr. Griliches had ever personally interviewed

provements that result in a reduced cost of production for the prod- one of the Midwestern farmers whose adoption of hybrid corn he was

uct, leading to a lower selling price to consumers. Economists call this trying to understand (instead of just statistically analyzing their ag-

"learning by doing" (Arrow, 1962). gregated behavior from secondary data sources), he would have

A good example is the pocket calculator, which sold for about understood that farmers are not 100 percent economic men.

$250 in 1972; within a few years, thanks to technological im- Not surprisingly, rather strong evidence refuting Griliches' asser-

provements in the production of the semiconductors that are a vital tion has been brought to bear on the controversy: (1) in the case of

part of the calculator, a similar (four-function) product sold for only hybrid sorghum adoption in Kansas (Brandner and Straus, 1959;

about $10. Brandner, 1960; Brandner and Kearl, 1964), where compatibility was

When the price of a new product decreases so dramatically during more important than profitability, and (2) for hybrid-seed corn adop-

its diffusion process, a rapid rate of adoption is obviously facilitated. tion in Iowa (Havens and Rogers, 1961b; Griliches, 1962; Rogers and

In fact, one might even question whether an innovation like the poc- Havens, 1962b), where it was concluded that a combination of an in-

ket calculator is really the same in 1976, when it cost $10, as in 1972 novation's profitability plus its observability were most important in

when it cost twenty-five times as much. Certainly, its absolute relative determining its rate of adoption. For other commentaries in this con-

advantage has increased tremendously. Here we see an illustration of troversy, see Griliches (1960b) and Babcock (1962). A recent re-

how a characteristic of an innovation changed as its rate of adoption analysis of Griliches' hybrid corn data by another economist (Dixon,

progressed. Thus, measuring the perceived characteristics of an inno- 1980) led to the general conclusion that profitability and compatibility

vation cross-sectionally at one point in time provides only a very are complements, not substitutes, in explaining the rate of adoption.

incomplete picture of the relationship of such characteristics to an in- So the original controversy seems to have died now to a close approx-

novation's rate of adoption. The characteristics may change as the in- imation of consensus.

novation diffuses.

A controversy regarding the relative importance of profitability

versus other perceived attributes of innovations for U.S. farmers can Status Aspects of Innovations

be traced through diffusion literature. Griliches (1957), an economist,

explained about 30 percent of the variation in rate of adoption of Undoubtedly one of the important motivations for almost any in-

hybrid corn on the basis of profitability. He used aggregate data from dividual to adopt an innovation is the desire to gain social status. For

U.S. crop-reporting districts and states, and hence, could not claim certain innovations, such as new clothing fashions, the social prestige

that similar results would obtain when individual farmers were the that the innovation conveys to its wearer is almost the sole benefit that

units of analysis. Griliches (1957) concluded: "It is my belief that in the adopter receives. In fact, when many other members of a system

the long run, and cross-sectionally, [sociological] variables tend to have also adopted the same fashion, the innovation (such as longer

cancel themselves out, leaving the economic variables as the major skirts or designer jeans) may lose much of its social value to the

determinants of the pattern of technological change." Griliches' adopters. This gradual loss of status giving on the part of a particular

strong assertion of the importance of profitability as a sole explana- clothing innovation provides a continual pressure for yet newer

tion of rate of adoption is consistent with the "Chicago School" of fashions.

economists, who assume that, in the absence of evidence to the con- The point here is not that certain new clothing styles do not have

trary, the market works. Market forces undoubtedly are of impor- functional utility for the wearer; for instance, jeans are an eminently

tance in explaining the rate of adoption of farm innovations. For practical and durable type of clothing. But certainly the main reason

some innovations (such as high-cost and highly profitable ideas) and for buying designer jeans has more to do with the designer's name on

for some farmers, economic aspects of relative advantage may even be the rear pocket, a status-conferring attribute of the innovation, than](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/diffusionofinnovations3rded-121130093410-phpapp02/85/Diffusion-of-innovations-3rd-ed-117-320.jpg)

![220

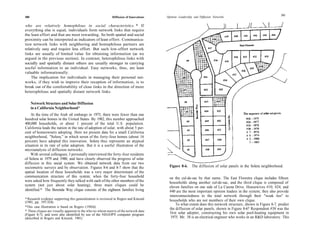

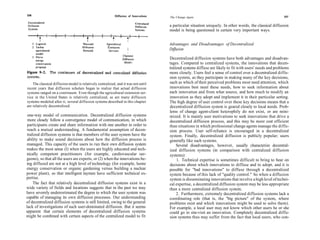

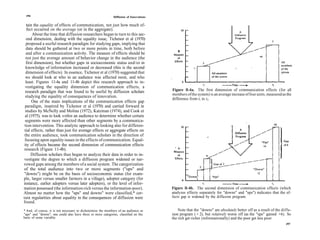

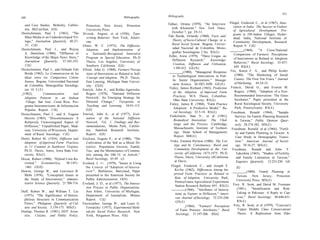

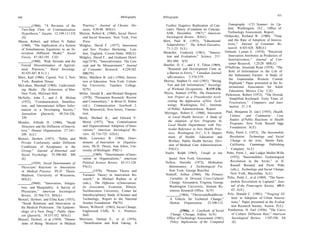

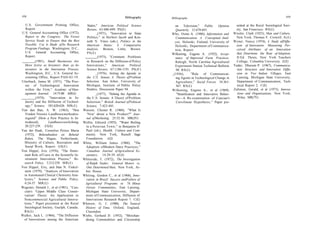

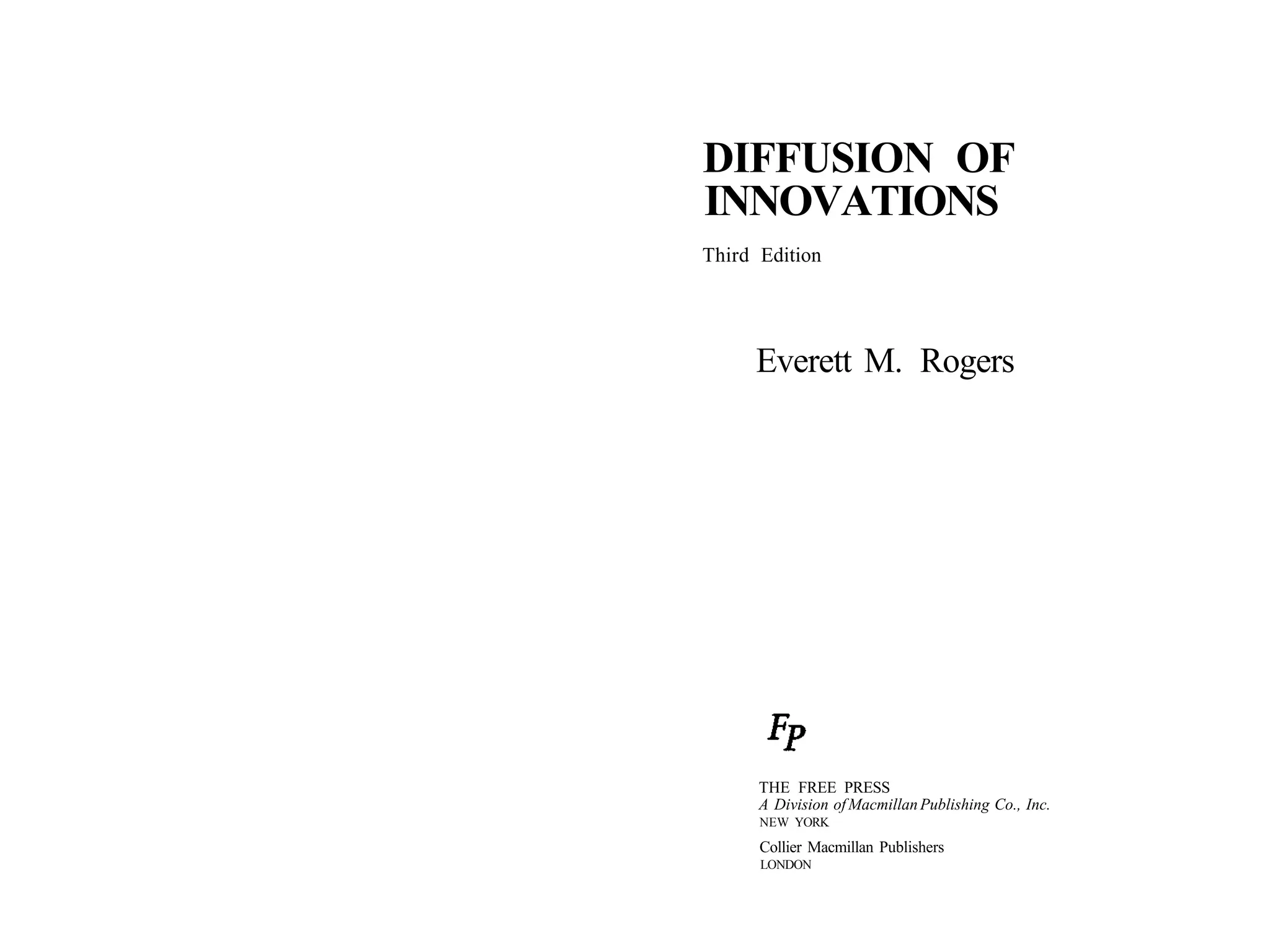

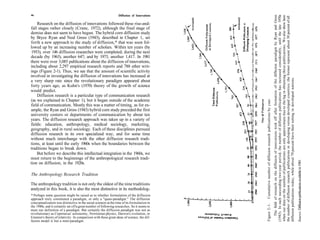

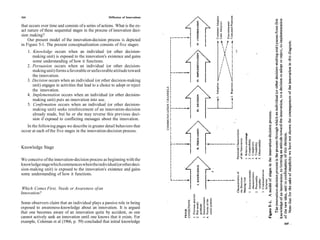

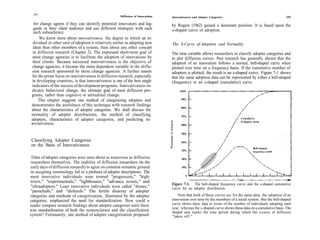

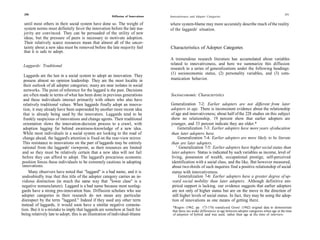

Table 6-1. Perceived Attributes of Innovations and Their Rate of Adoption.

Number of Percentage of

Number of Attributes of Variance in Attributes of Innovations

Author(s) of Type of Innovations Innovations Rate of Adoption Found to be Significantly

Investigations Respondents Studied Measured Explained Related to Rate of Adoption

1. Kivlin (1960); Fliegel 229 Pennsylvania 43 [] 51 (1) Relative advantage

and Kivlin (1962). farmers (2) Compatibility

(3) Complexity

2. Tucker (1961) 88 Ohio farmers 13 6 — None

3, Mansfield (1961) Coal, steel, brewing, 12 2 50 (1) Relative advantage (profit-

and railroad firms ability)

(2) Observability (rale of inter-

action about the innovation

among the adopters)

4. Fliegel and Kivlin 229 Pennsylvania 33 15 51 (1) Trialabilily

(1966a) farmers* (2) Relative advantage (initial cost)

5. Petrini (1966) 1,845 Swedish 14 2 71 (1) Relative advantage

farmers (2) Complexity

6. Singh (1966) 130 Canadian 22 10 87 (1) Relative advantage (rate of

farmers cost recovery, financial

return, and low initial cost)

(2) Complexity

(3) Trialability

(4) Observability

7. Kivlin and Fliegel 80 small-scale 33 15 51 (1) Relative advantage (savings

(1967a); Kivlin and Pennsylvania of discomfort)

Fliegel (1967b) farmers (and 229

large-scale

farmers)

8. Fliegel et al 387 Indian peasants 50 12 58 (1) Relative advantage (social

(1968) approval, continuing cost,

and time-saving)

(2) Observability (clarity of

results)

SO small-scale 33 12 62 (1) Relative advantage (savings

Pennsylvania of discomfort, payoff, and

farmers † time saving)

229 large-scale 33 12 49 (1) Trialability

Pennsylvania (2) Relative advantage (initial

farmers‡ cost)

9. Clinton (1973) 383 elementary 18 16 55 (1) Relative advantage (including

school teachers cost)

in Canada (2) Complexity

(3) Compatibility

(4) Observability

10. Hahn (1974) 209 U.S. 22 5+ (1) Observability

teachers (2) Complexity

(3) Compatibility

11. Holloway (1977) 100 high-school 1 5+ (1) Relative advantage and

principals compatibility

(2) Complexity

(3) Trialability

(4) Observability

12. Allan and Wolf 100 school staff — 5 — (1) Complexity

(1978) members

*The same 229 Pennsylvania farmers are involved in this study as in Kivlin (1960) above, but 33 instead of 43 innovations, and 15 instead of 11 attributes, were

analyzed. Hence, the results are different.

† These are the same 80 small-scale Pennsylvania farmers as in Kivlin and Fliegel (l%7a), but 12 instead of 15 attributes are included in the multiple-correlation

prediction of rate of adoption; the results obtained are therefore different,

‡ These are the 229 large-scale Pennsylvania farmers in Kivlin (1960) above, but a different number of innovations and attributes are included in the analysis;

hence, the results are different.

221](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/diffusionofinnovations3rded-121130093410-phpapp02/85/Diffusion-of-innovations-3rd-ed-120-320.jpg)

![228 229

Diffusion of Innovations Attributes of Innovations and Their Rate of Adoption

prior to its release. On the other hand, public change agencies gener- she behaves toward other ideas that the individual perceives as similar

ally do not realize the importance of what an innovation is called. to the new idea. For instance, consider a category of existing products

The perception of an innovation is colored by the word-symbols consisting of products A, B, and C. If a new product, X, is introduced

used to refer to it. The selection of an innovation's name is a delicate to the audience for these products, and if they perceive X as similar to

and important matter. Words are the thought units that structure our B, but unlike A and C, then consumers who bought B will be just as

perceptions. And of course it is the potential adopters' perceptions of likely to buy X as B. If other factors (like price) are equal, X should at-

an innovation's name that affect its rate of adoption. Sometimes a tain about one-half of the former B consumers, but the introduction

medical or a chemical name is used for an innovation that comes from of X should not affect the sales of products A and C. Further, if we

medical or chemical research and development; unfortunately, such can learn why consumers perceive B and X as similar, but different

names are not very meaningful to potential adopters (unless they are from A and C, X can be positioned (through its name, color, packag-

physicians or chemists). Examples are "2,4-D weed spray," "IR-20 ing, taste, and the like) so as to maximize its distance from A, B, and C

rice variety," and "intrauterine device," terms that were confusing in the minds of consumers, and thus to gain a unique niche for the new

and misunderstood by farmers or family planning adopters. A new in- idea.

trauterine device, the "copper-T," was introduced in South Korea Obviously, the positioning of an innovation rests on accurately

without careful consideration of an appropriate Korean name. The measuring its compatibility with previous ideas.

letter "T" does not exist in the Korean alphabet, and copper is con- Research to position new products is often conducted by market

sidered a very base metal and has a very unfavorable perception. researchers, and many of the methods for positioning an innovation

Thus, one could hardly have chosen a worse name (Harding et al, have been developed by commercial researchers. But these positioning

1973). techniques can be used to ease the introduction of any type of innova-

In contrast, the word "Nirodh" was carefully chosen in India in tion. For instance, Harding et al (1973, p. 21) used positioning

1970 as the most appropriate term for condoms. Prior to this time, methods to introduce the copper-T, a new intrauterine device in

condoms had a very negative perception as a contraceptive method; Korea. First, they asked a small sample of potential adopters to help

they were thought of mainly as a means of preventing venereal identify twenty-nine perceived attributes of eighteen contraceptive

disease. When the government of India decided to promote condoms methods in an open-ended, unstructured approach. Then another

as a contraceptive method, they pretested a variety of terms. sample of Korean respondents were asked to rate each of the eighteen

"Nirodh," a Sanskritic word meaning "protection," was selected, family planning methods (including the copper-T, the only new

and then promoted in a huge advertising campaign to the intended au- method) on these thirty-nine attributes (which included numerous

dience (Rogers, 1973, p. 237). The result was a sharp increase in the subdimensions of the five main attributes discussed in this chapter).

rate of adoption of "Nirodhs."* The result was a series of recommendations about which attributes of

We recommend such a receiver-oriented, empirical approach to the copper-T should be stressed in its diffusion campaign, in order to

naming an innovation, so that a word-symbol that has the desired maximize its rate of adoption. For instance, Harding et al (1973, p. 10)

meaning to the audience is chosen. recommended stressing the copper-T's long lifetime, its reliability (in

preventing unwanted pregnancies), its lack of interference with sexual

life, and its newness. These researchers also recommended a change in

Positioning an Innovation the physical nature of the copper-T: "Certain features of the copper -

T, such as the string [a plastic thread used to remove the intrauterine

A basic assumption of positioning research is that an individual will device], perhaps should be altered since the string is associated with

behave toward a new idea in a manner that is similar to the way he or causing bacteria to enter the womb and with causing an inflammation

of the womb" (Harding et al, 1973, p. 11).

*In part, because use of the word "Nirodh" helped overcome the tabooness of con- Positioning research, thus, can help identify an ideal niche for an

doms. Taboo communication is a type of message transfer in which the messages are innovation to fill relative to existing ideas in the same field. This ideal

perceived as extremely private and personal in nature because they deal with pro-_

scribed behavior. niche is determined on the basis of the new idea's position (in the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/diffusionofinnovations3rded-121130093410-phpapp02/85/Diffusion-of-innovations-3rd-ed-124-320.jpg)

![240 Diffusion of Innovations

as perceived by members of a social system, is positively related to its

rate of adoption (Generalization 6-4). CHAPTER 7

Observability is the degree to which the results of an innovation

are visible to others. The observability of an innovation, as perceived

by members of a social system, is positively related to its rate of adop- Innovativeness and Adopter

tion (Generalization 6-5).

Rate of adoption is the relative speed with which an innovation is Categories

adopted by members of a social system. In addition to the perceived

attributes of an innovation, such other variables affect its rate of

adoption as (1) the type of innovation decision, (2) the nature of com-

munication channels diffusing the innovation at various stages in the Be not the first by whom the new are tried,

innovation-decision process, (3) the nature of the social system, and Nor the last to lay the old aside.

(4) the extent of change agents' efforts in diffusing the innovation. Alexander Pope (1711),

The diffusion effect is the cumulatively increasing degree of in- An Essay of Criticism, Part II.

fluence upon an individual to adopt or reject an innovation, resulting

from the activation of peer networks about an innovation in a social The innovator makes enemies of all those who prospered under the old

order, and only luke-warm support is forthcoming from those who would

system. As the rate of awareness knowledge in a social system in-

prosper under the new.

creases up to about 20 or 30 percent, there is very little adoption, but Niccolo Machiavelli

once this threshold is passed, further increases in awareness (1513, p. 51), The Prince.

knowledge lead to increases in adoption. The diffusion effect is

greater in a social system with a higher degree of interconnectedness A slow advance in the beginning, followed by rapid and uniformly ac-

(the degree to which the units in a social system are linked by interper- celerated progress, followed again by progress that continues to slacken—

sonal networks). The degree of interconnectedness in a social system is until it finally stops: These are the three ages o f . . . invention . . . . If

taken as a guide by the statistician and by the sociologist, [they] would

positively related to the rate of adoption of innovations (Generaliza- save many illusions.

tion 6-6).

Overadoption is the adoption of an innovation when experts feel Gabriel Tarde (1903, p. 127),

that it should be rejected. The Laws of Imitation.

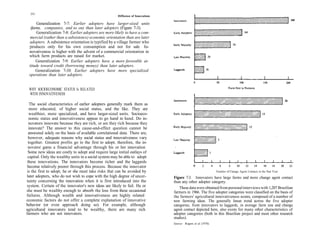

NOT ALL INDIVIDUALS IN A SOCIAL SYSTEM adopt an innovation

at the same time. Rather, they adopt in a time sequence, and they may

be classified into adopter categories on the basis of when they first

begin using a new idea. We could describe each individual adopter in a

social system in terms of his or her time of adoption, but this would be

tedious work. It is much easier and more meaningful to describe

adopter categories (the classifications of members of a system on the

basis of innovativeness), each of which contains individuals with a

similar degree of innovativeness. There is much practical usefulness

241](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/diffusionofinnovations3rded-121130093410-phpapp02/85/Diffusion-of-innovations-3rd-ed-130-320.jpg)

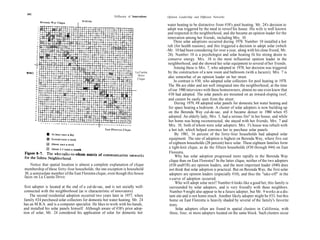

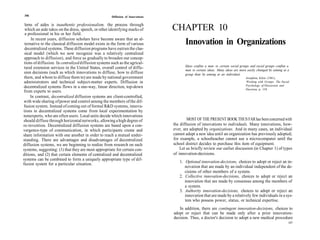

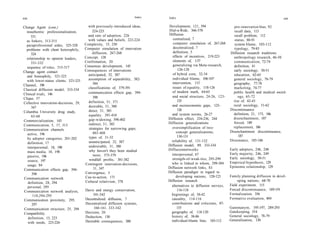

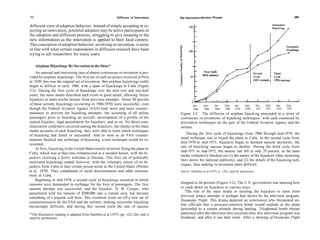

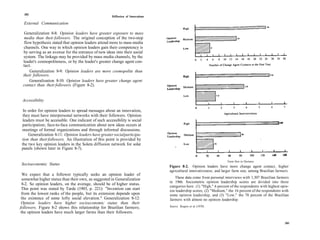

![292 Diffusion of Innovations Opinion Leadership and Diffusion Networks 293

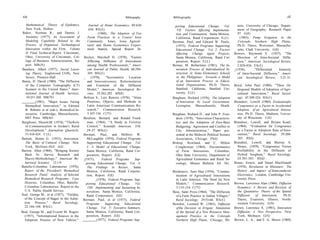

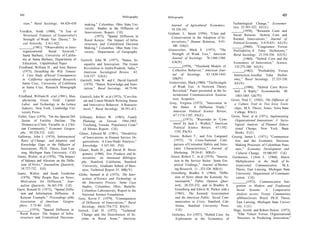

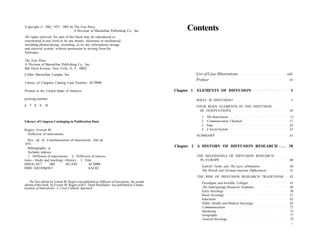

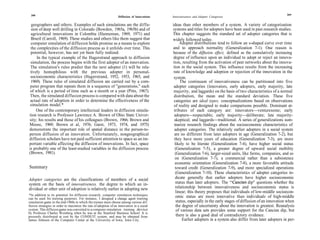

process for gammanym. Figure 8-3 shows a stylized rate of adoption for the tion of the innovation. This shared opinion led the interconnected doctors to

interconnected versus the isolated doctors, which is based on the general adopt the new drug rapidly, and eventually the medical community's

results of plotting actual adoption rates for the interconnected and isolated favorable view of the innovation trickled out to the relatively isolated doc-

physicians for various sociometric measures (such as friendship, the discus- tors on the social margins of the network.

sion of patient cases, and office partnerships). It can be observed in Figure Thus, one can think of a social system as going through a gradual learn-

8-3 that the s-curve for the interconnected doctors takes off rapidly in a kind ing process regarding an innovation, as the aggregated experience of the in-

of snowballing process in which an innovator conveys his or her personal ex- dividuals with the new idea builds up and is shared among them through in-

perience with the innovation to two or more of his or her peers, who each terpersonal networks.

may then adopt and, in the next time period, interpersonally convey their What were the actual contents of the network messages exchanged

personal experience with the new idea to two or more other doctors, and so among the medical doctors about gammanym? Coleman et al (1966) did not

on. Within several months, almost all of the interconnected doctors have find out, unfortunately. They speculate that the doctors may have talked

adopted and their rate of adoption then necessarily begins to level off. This about the drug's existence, its price, its efficacy as a cure, or about the occur-

contagion process occurs because of the interpersonal networks that link the rence of undesirable side effects: "Perhaps Dr. A, who had used the drug,

individuals, thus providing communication avenues for the exchange of advised Dr. B to do likewise; perhaps Dr. B copied Dr. A without being told;

evaluative information about the innovation. perhaps Drs. A and B made a joint decision" (Coleman et al, 1966, pp.

The chain-reaction snowballing of adoption does not happen, however, 111-112). Future research needs to investigate the content of interpersonal

for the relatively isolated individuals, who lack peer-network contacts from messages about an innovation; the usual methodology of diffusion research

which to learn about their subjective evaluations of the innovation. So the and of communication network analysis does not provide feasible means of

isolated individuals' rate of adoption is almost a straight line, curving obtaining such network message content (Rogers and Kincaid, 1981). But

slightly because the number of new adopters in each period remains a con- appropriate techniques of study could easily be devised to capture these

stant percentage of those who have not already adopted the innovation previously invisible message contents.

(Figure 8-3). There is no sudden take-off in the rate of adoption for the

isolated individuals. But eventually most or all of these isolated individuals

will adopt; this is not shown in Figure 8-3 because Coleman et al (1966) con-

ducted their data gathering in the seventeenth month after the release of

Diffusion Networks

gammanym, when only about 75 percent of their isolated doctors had

adopted the drug. As we have just shown, the heart of the diffusion process is the model-

In other words, interconnected doctors were more innovative in adopting ing and imitation by potential adopters of their near-peers who have

gammanym mainly because their rate of adoption was shaped differently previously adopted a new idea. In deciding whether or not to adopt an

from the rate of adoption for more isolated doctors. Thanks to their in- innovation, we all depend mainly on the communicated experience of

terpersonal networks, interconnected individuals have a faster trajectory to others much like ourselves who have already adopted. These subjec-

their S-shaped diffusion curve; hence, on the average they are more in-

tive evaluations of an innovation mainly flow through interpersonal

novative than the isolated doctors whose rate of adoption is almost a straight

line. Presumably, if the more isolated doctors had indeed been completely networks. For this reason, we must understand the nature of networks

isolated, they would have adopted even more slowly, if at all. "The impact if we are to comprehend the diffusion of innovations fully.

[of networks] upon the integrated doctors was quick and strong; the impact Networks can serve as important connections to information

upon isolated doctors was slower and weaker, but not absent" (Coleman et resources, as the following examples (provided by Johnson and

"al, 1966, p. 126). Browning, 1979) imply:

When the doctors were confronted with making a decision about the new

drug in an ambiguous situation that did not speak for itself, they turned to

• A public relations executive receives a phone call from the owner

each other for information that would help them make sense out of the new of an airport where he occasionally rents hot air balloons. The

stimulus. Doctors who are closely linked in networks tend to interpret the in- owner is interested in contacting movie actor Jerry Lewis to

novation similarly. In the case of gammanym, the medical community donate balloon rides for the Lewis annual telethon; he has heard

studied by Coleman et al (1966, p. 119) gradually arrived at a positive percep- that the executive knows Lewis. . . .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/diffusionofinnovations3rded-121130093410-phpapp02/85/Diffusion-of-innovations-3rd-ed-156-320.jpg)

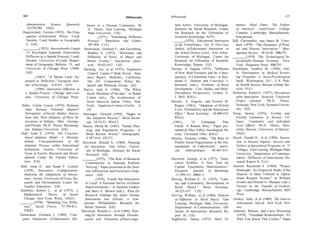

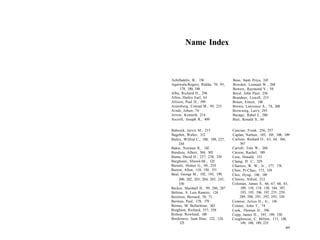

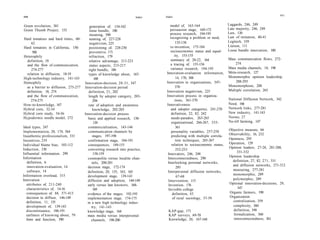

![Opinion Leadership and Diffusion Networks 297

heterophilous individuals who were not very close friends. These

"weak ties" occurred with individuals "only marginally included in

the current network of contacts, such as an old college friend or a

former workmate or employer, with whom sporadic contact had been

maintained"(Granovetter, 1973). Chance meetings with such ac-

quaintances sometimes reactivated these weak ties, leading to the ex-

change of job information with the individual.

Only 17 percent of Granovetter's Newton respondents said they

found their new job through close friends or relatives.* Why were

weak ties so much more important than strong network links? Be-

cause an individual's close friends seldom know much that the in-

dividual does not also know. One's intimate friends are usually friends

of each other's, forming a close-knit clique; such an ingrown system is

an extremely poor net in which to catch new information fron one's

environment. Much more useful as a channel for gaining such infor-

mation are an individual's more distant acquaintances; they are more

likely to possess information that the individual does not already

possess, such as about a new job or about an innovation. Weak ties

connect an individual's small clique of intimate friends with another,

distant clique; as such, it is the weak ties that provide intercon-

nectedness to a total system. The weak ties are often bridging links,*

connecting two or more cliques. If these weak ties were somehow

removed from a system, the result would be an unconnected set of

separate cliques. So even though the weak ties are not a frequent path

for the flow of communication, the information that does flow

through them plays a crucial role for individuals and for the system.

This great importance of weak ties in conveying new information is

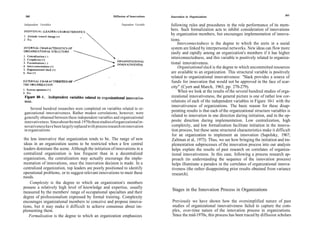

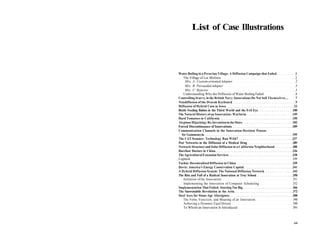

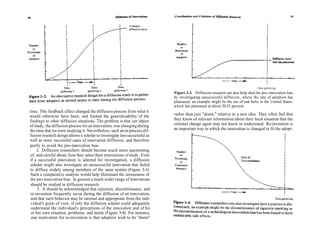

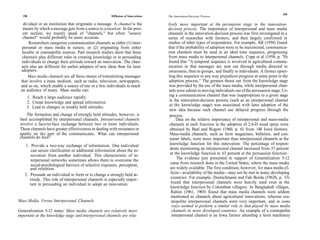

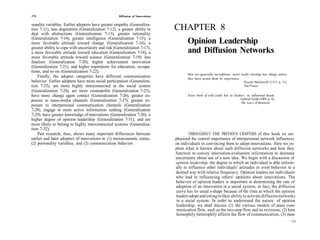

CD have high

communication proximity why Granovetter (1973) called his theory "the-[informational]

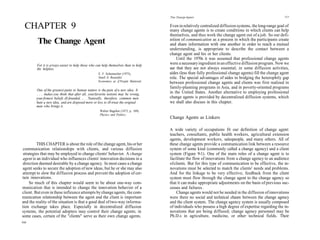

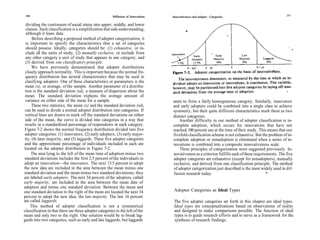

Figure 8-4. Communication proximity is the degree to which two in- strength-of-weak [network]-ties.''

dividuals have overlapping personal communication networks. The weak-versus-strong-ties dimension is more correctly and

precisely called communication proximity, defined previously as the

Both pairs of individuals A-B and C-D have direct communication, but

C-D are more proximate because they are also connected by four indirect degree to which two individuals in a network have personal com-

links. In other words, individuals C and D have personal communication munication networks that overlap. Figure 8-5 shows that weak ties are

networks that overlap, while A and B do not. This means that C-D are more low in communication proximity. At least some degree of heterophily

likely to exchange information than are A-B. Communication proximity is must be present in network links in order for the diffusion of innova-

the basis for assigning individuals to cliques, and thus is the criterion for tions to occur, as we have shown previously in this chapter. The low-

determining the communication structure of a system.

* Similar evidence of the importance of weak ties in the diffusion of information

Source: Adopted from Alba and Kadushin (1976). about new jobs is provided by Langlois (1977), Lin et al (1981), and Friedkin (1980),

but not by Murray et al (1981). An overall summary is provided by Granovetter

(1980).

* A bridge is an individual who links two or more cliques in a system from his or her

position as a member of one of the cliques.

296](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/diffusionofinnovations3rded-121130093410-phpapp02/85/Diffusion-of-innovations-3rd-ed-158-320.jpg)