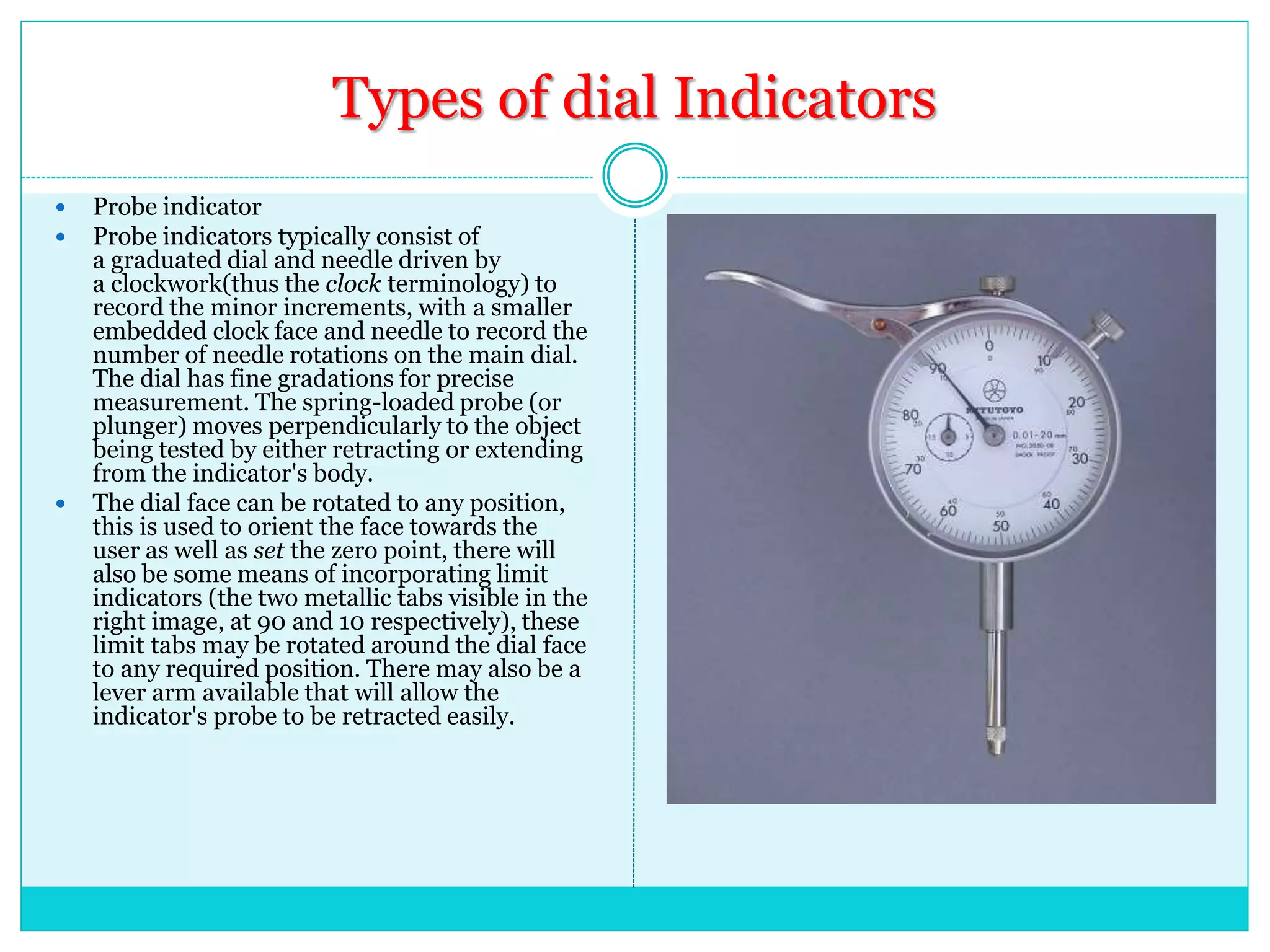

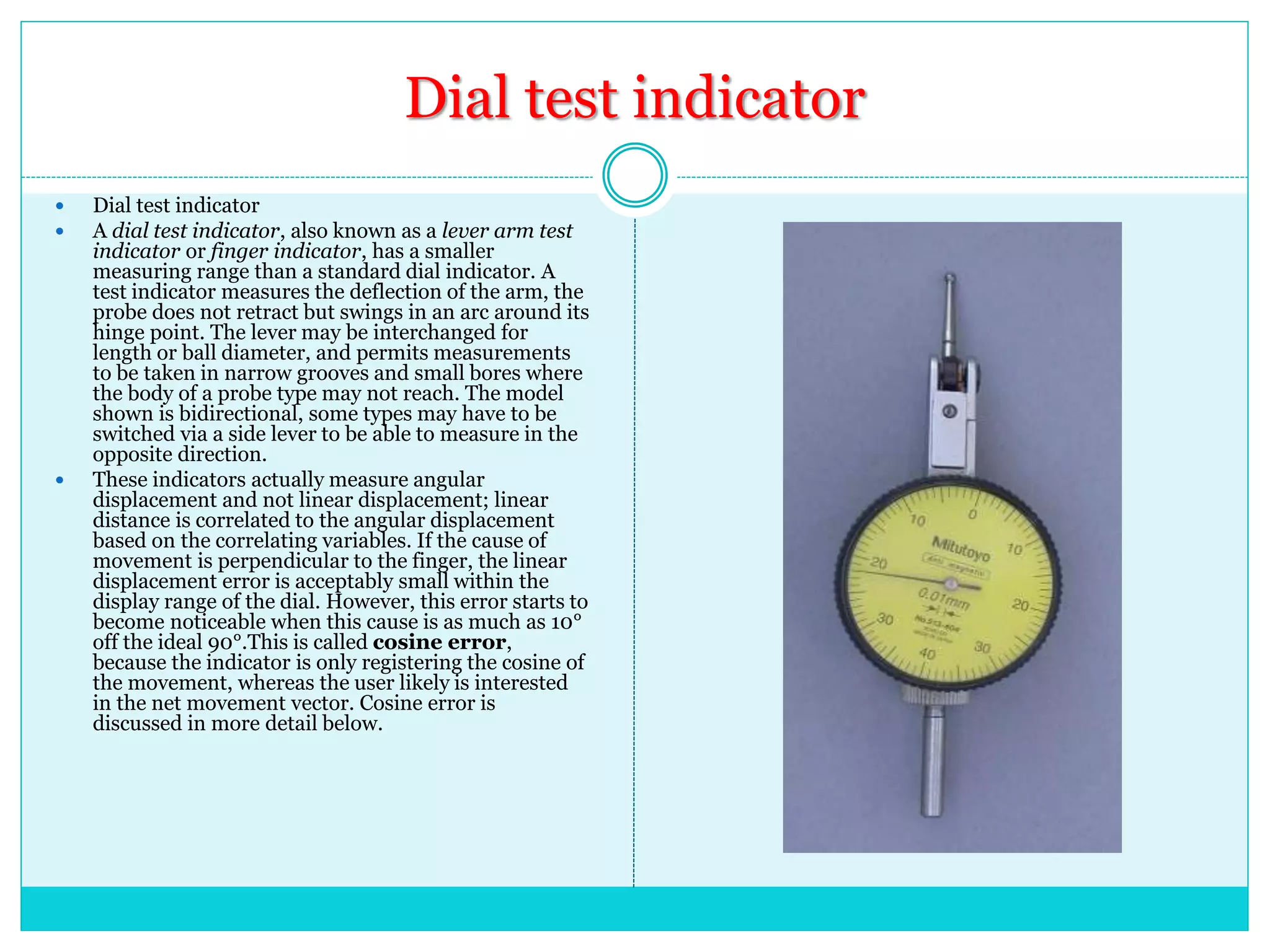

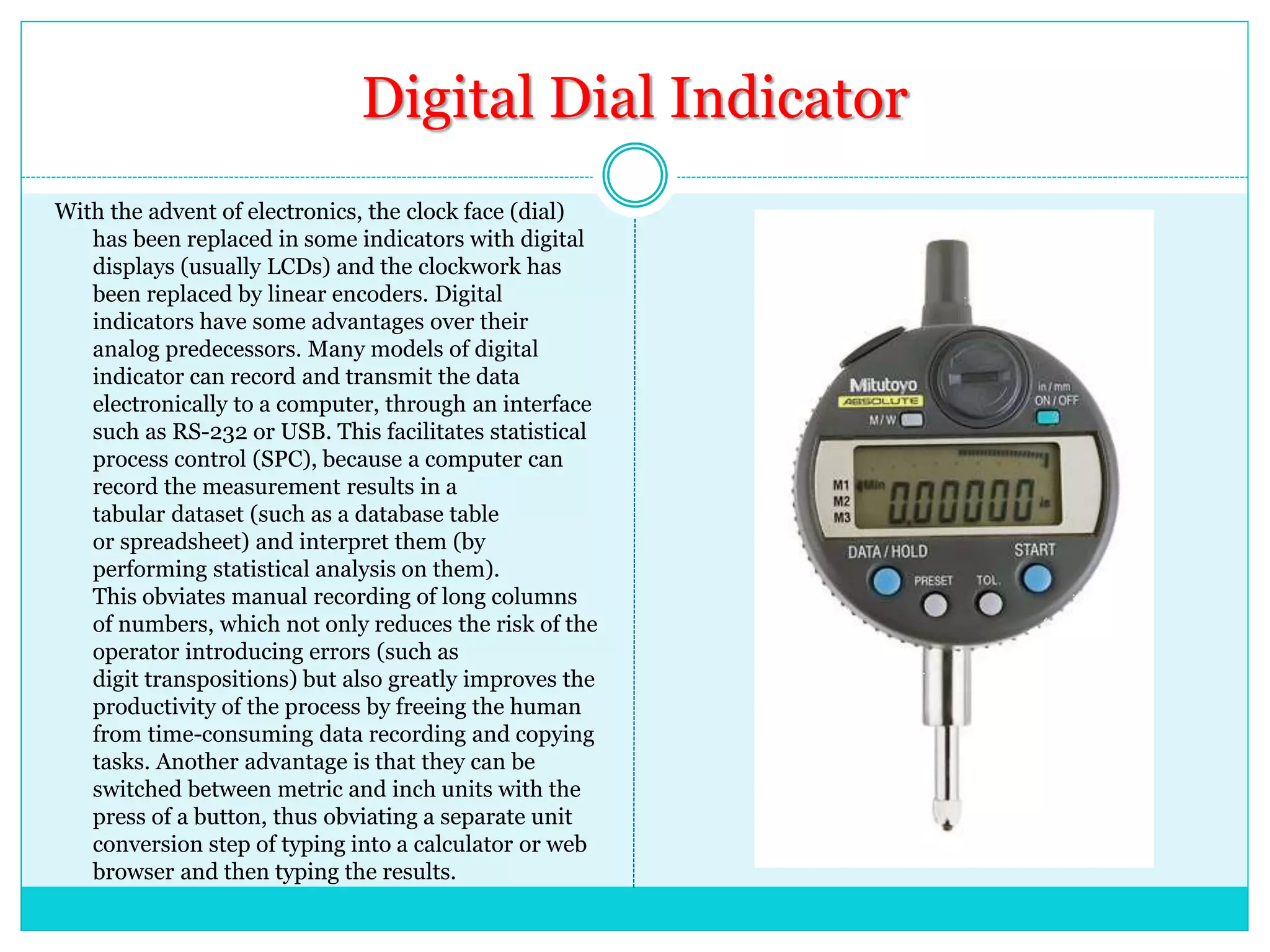

The document discusses dial indicators, which are precision measurement tools used to measure small distances and angles. It describes the basic components and principles of dial indicators, including different types such as probe indicators, dial test indicators, and digital dial indicators. It also covers their various applications in manufacturing and quality control processes, as well as tips for different indicator styles.