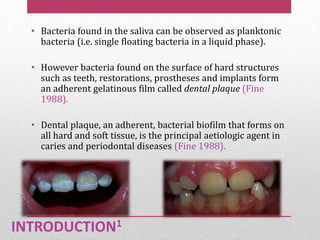

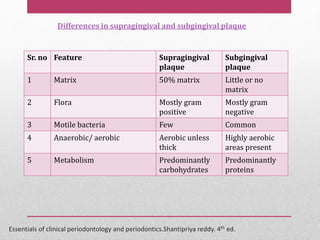

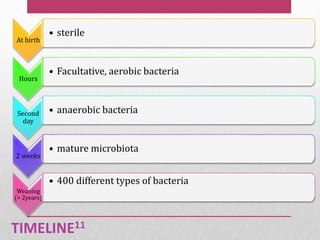

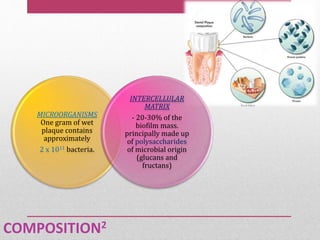

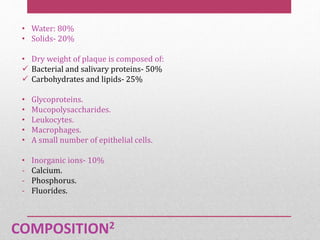

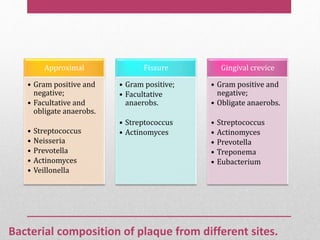

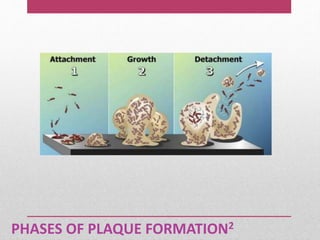

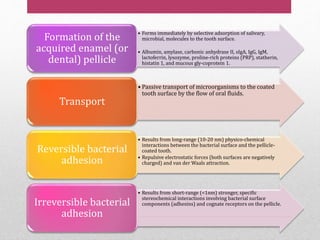

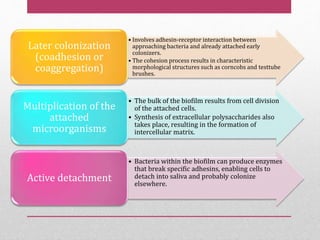

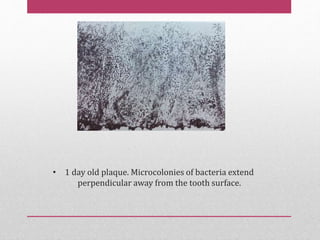

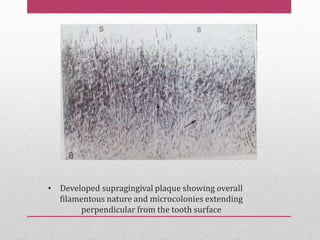

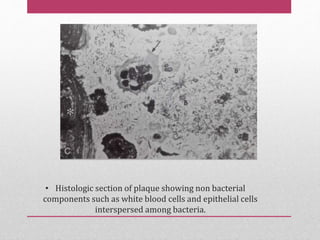

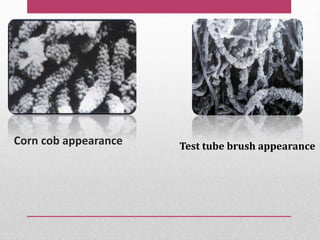

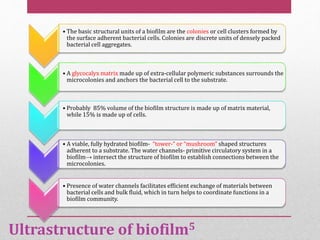

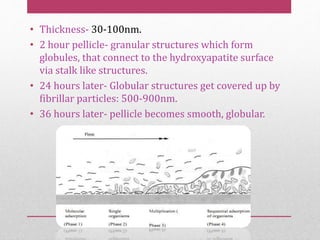

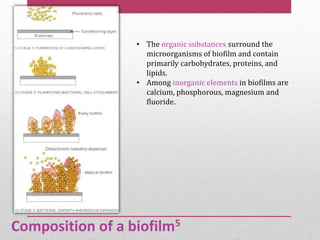

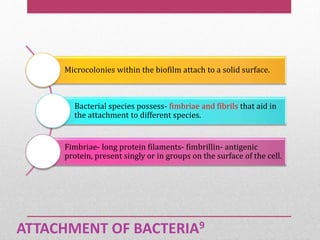

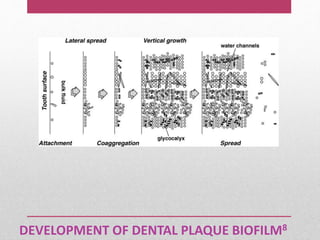

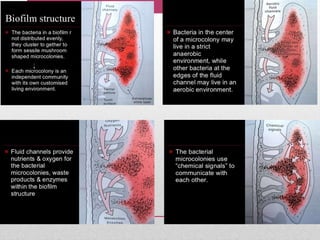

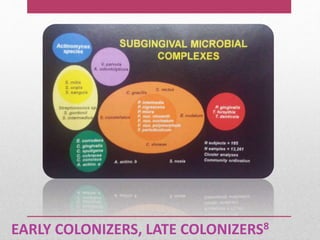

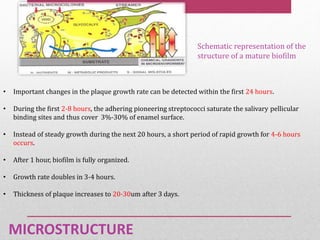

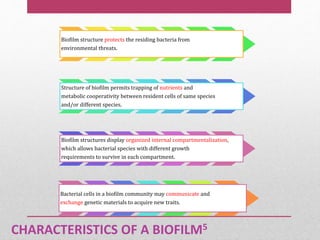

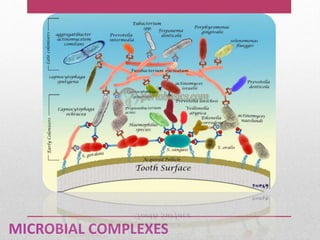

Dental plaque is a biofilm that forms on teeth and other oral surfaces. It is composed of bacteria embedded in an extracellular matrix. As plaque develops over time, the bacterial composition changes from primarily aerobic gram-positive bacteria to include more gram-negative and anaerobic bacteria. Plaque forms in distinct phases - initially with reversible bacterial adhesion to the acquired pellicle on the tooth surface, followed by irreversible adhesion and growth of microcolonies within the matrix. Mature plaque has a complex structure as a biofilm with water channels and bacterial clusters. Dental plaque is the primary cause of dental caries and periodontal disease.