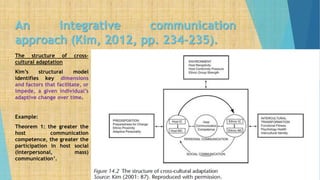

1) The document discusses Kim's integrative communication theory of cross-cultural adaptation. The theory views adaptation as a communication process where individuals establish relationships in new environments over time.

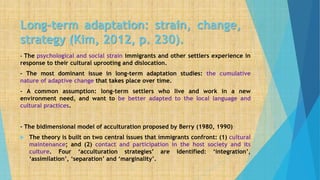

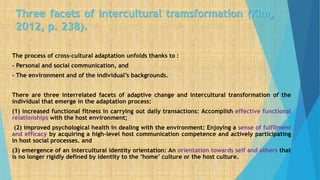

2) The adaptation process involves stress, learning new cultural practices, and developing host communication competence. It follows a cumulative, progressive trajectory as individuals participate more in the host culture.

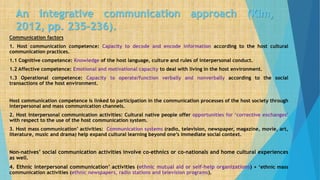

3) Key factors that influence adaptation are an individual's host communication competence, participation in host social interactions, as well as characteristics of the host environment like receptivity and pressure to conform.