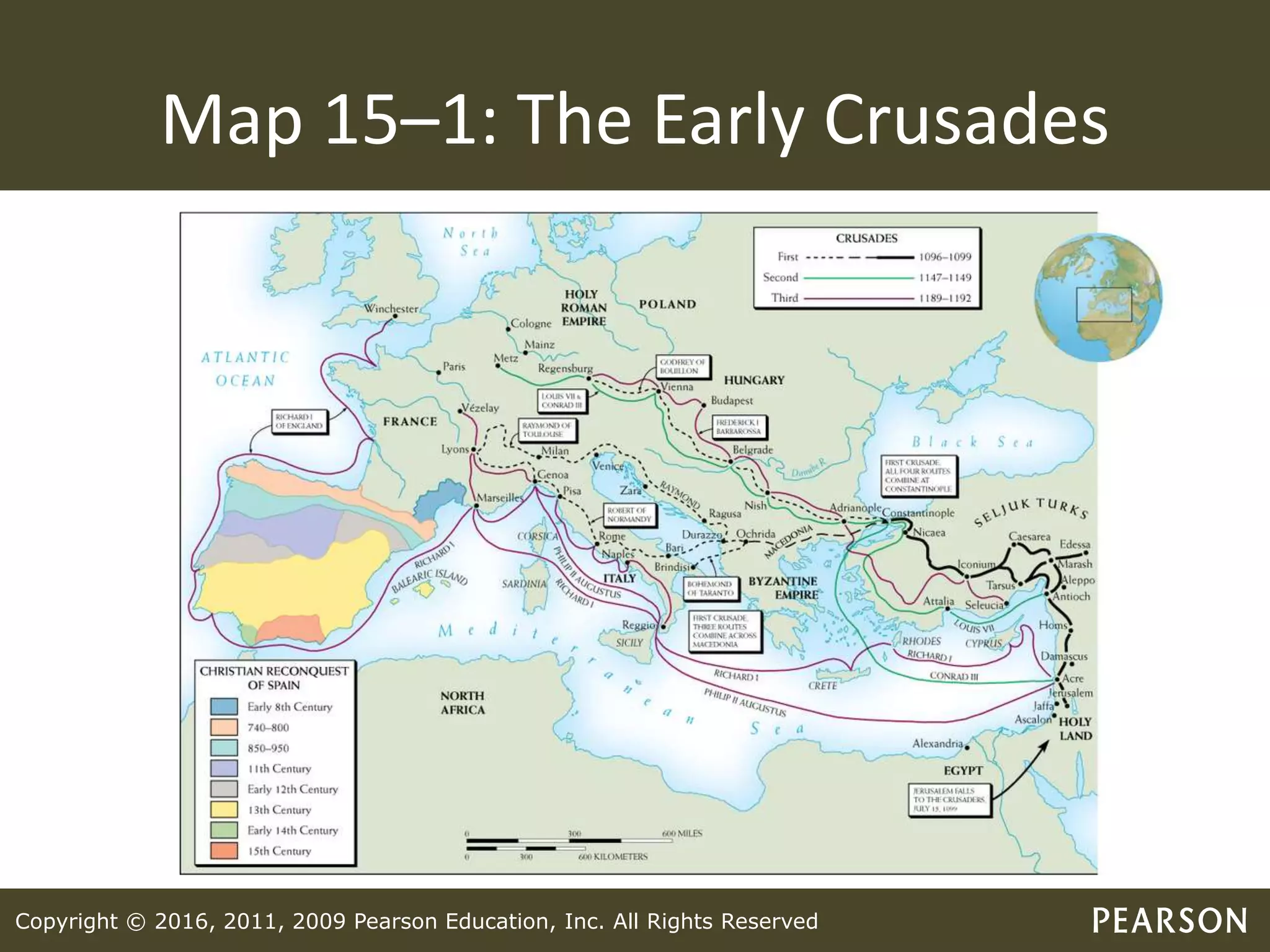

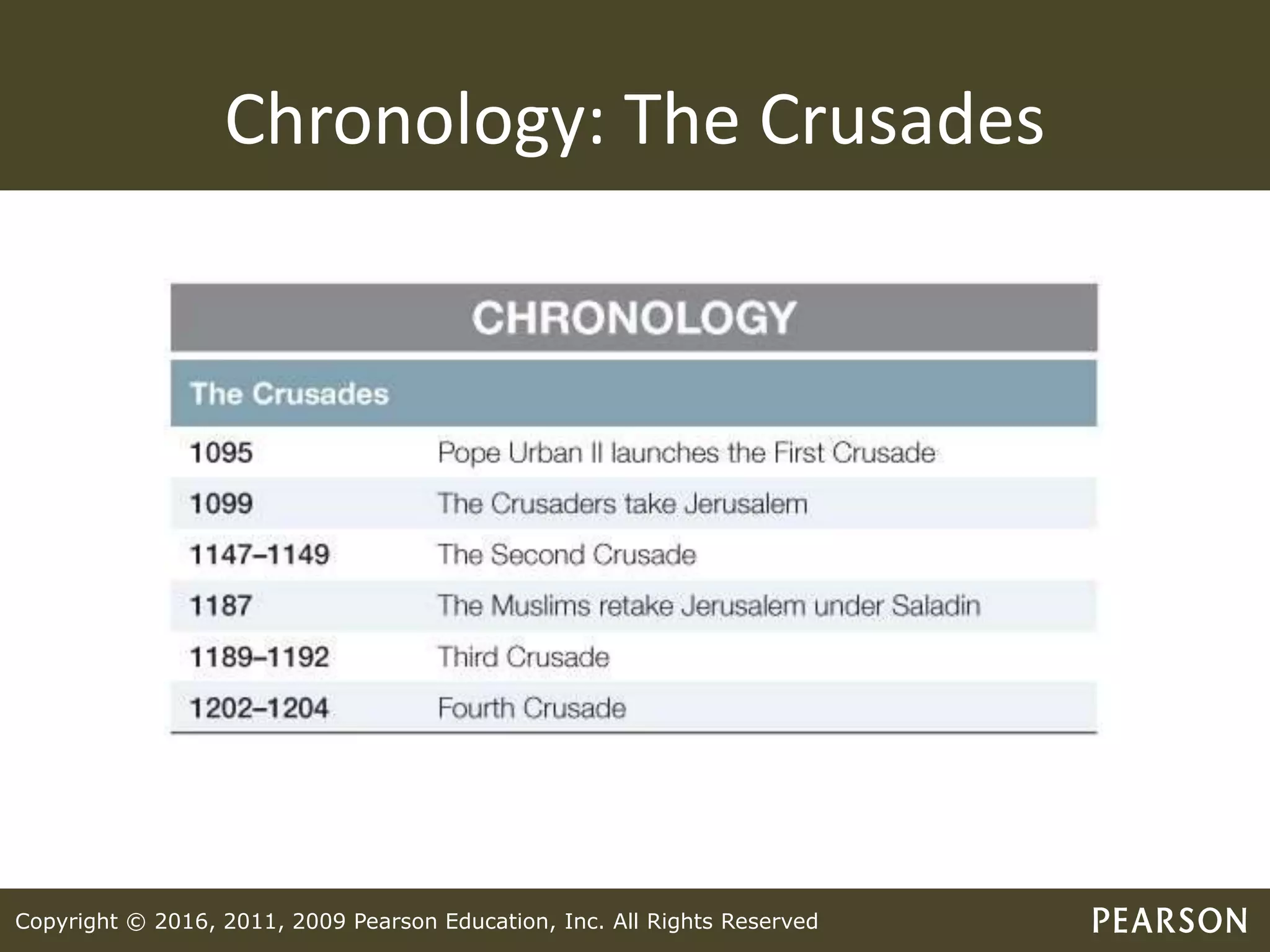

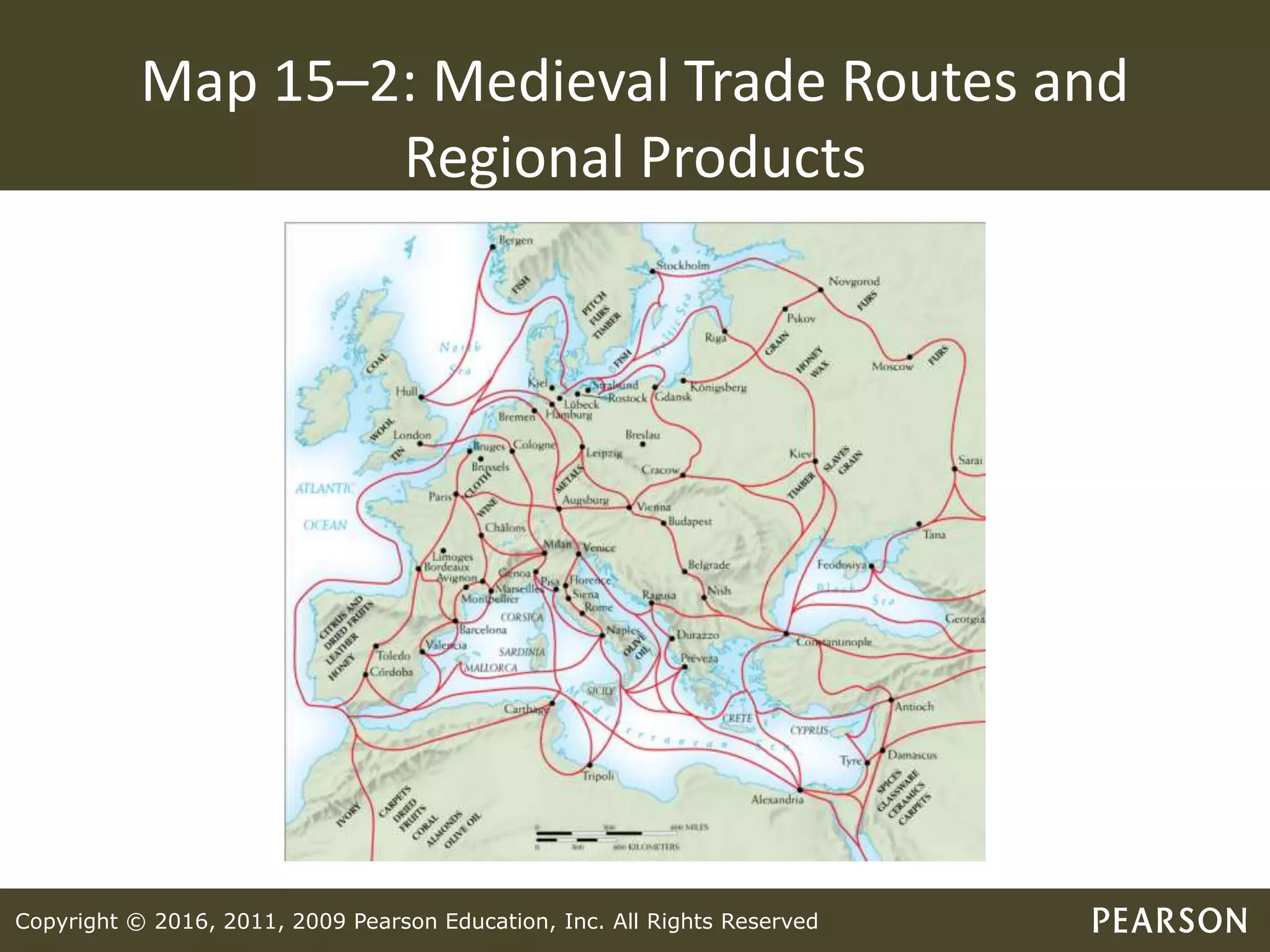

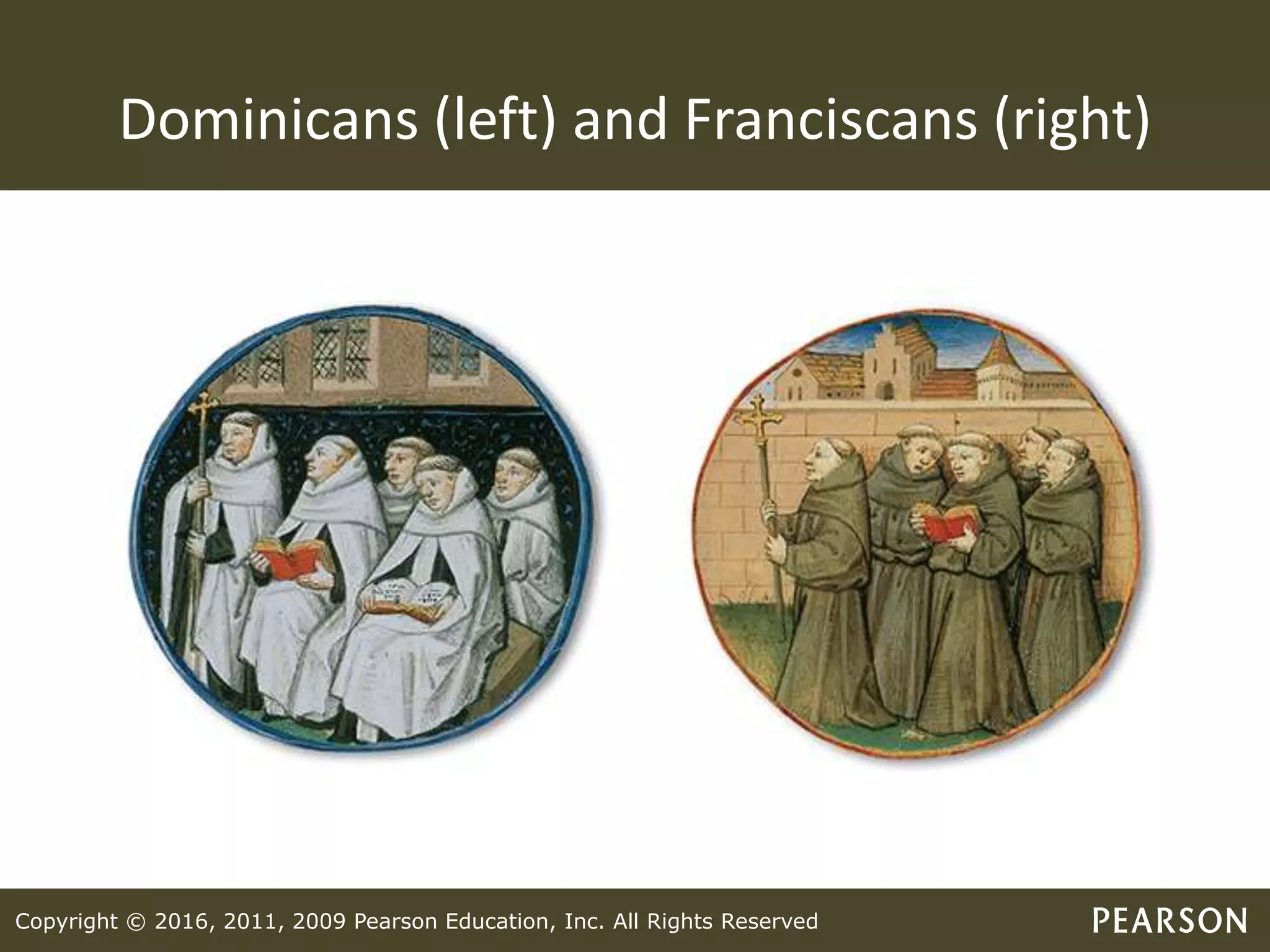

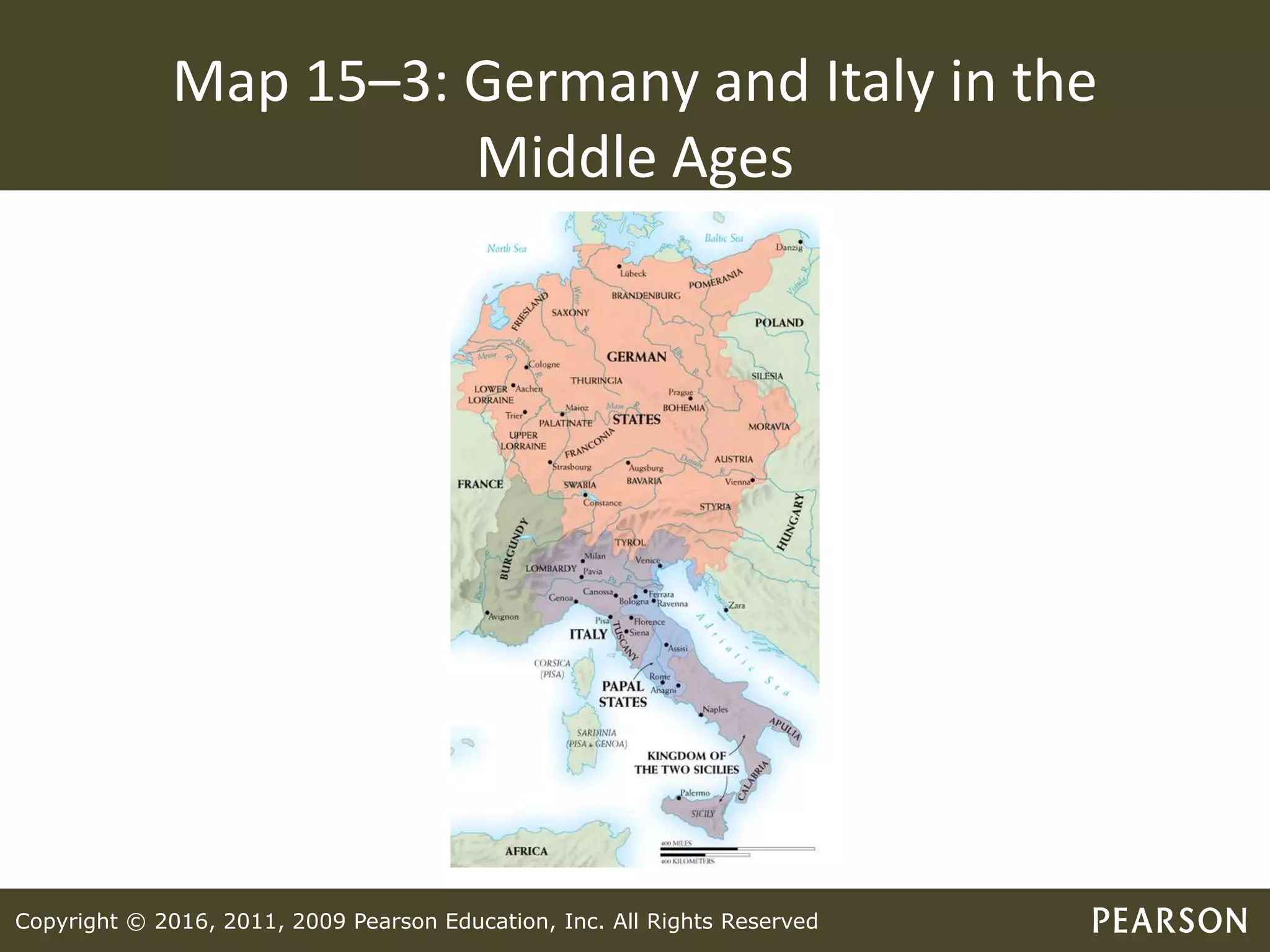

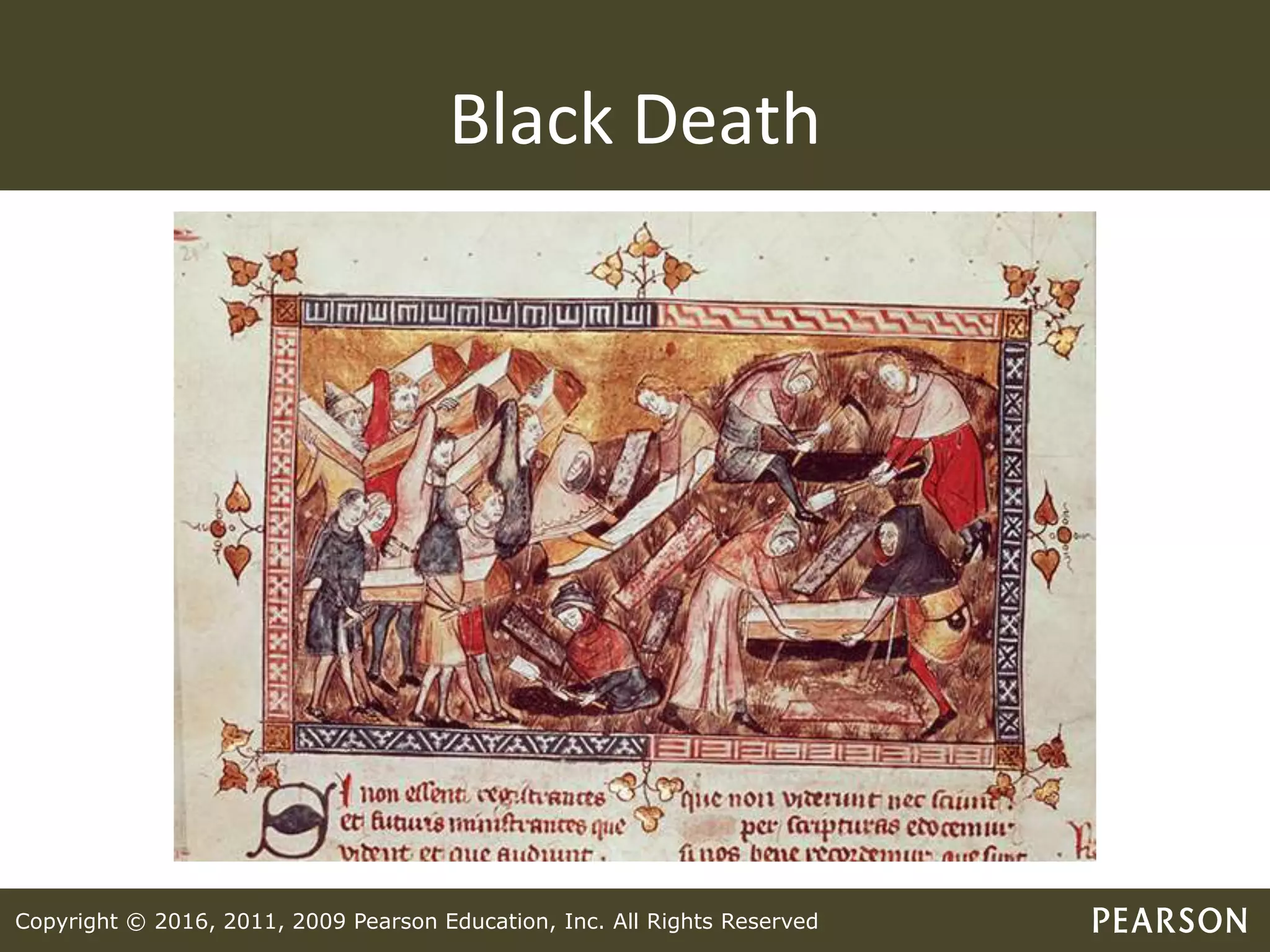

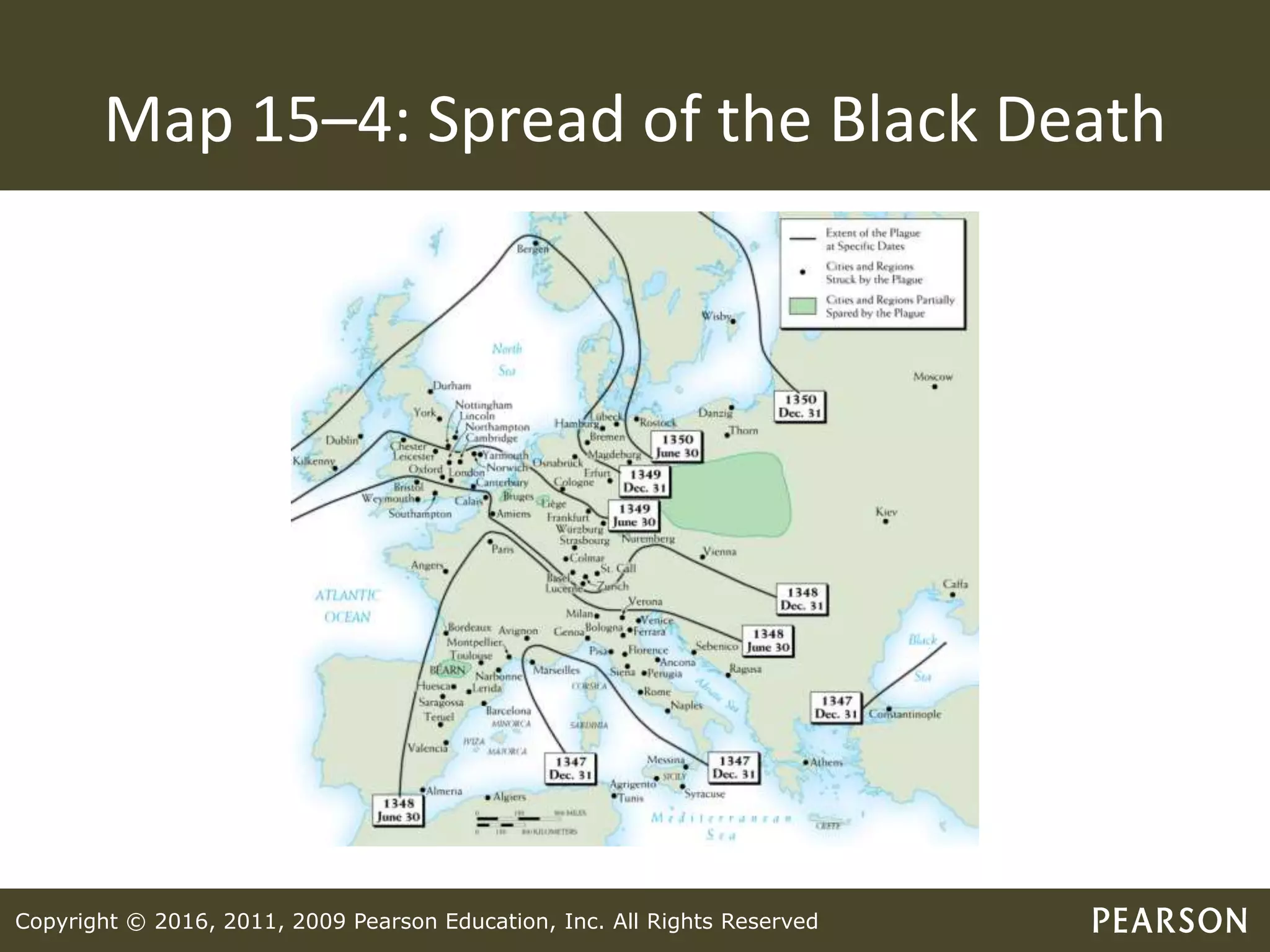

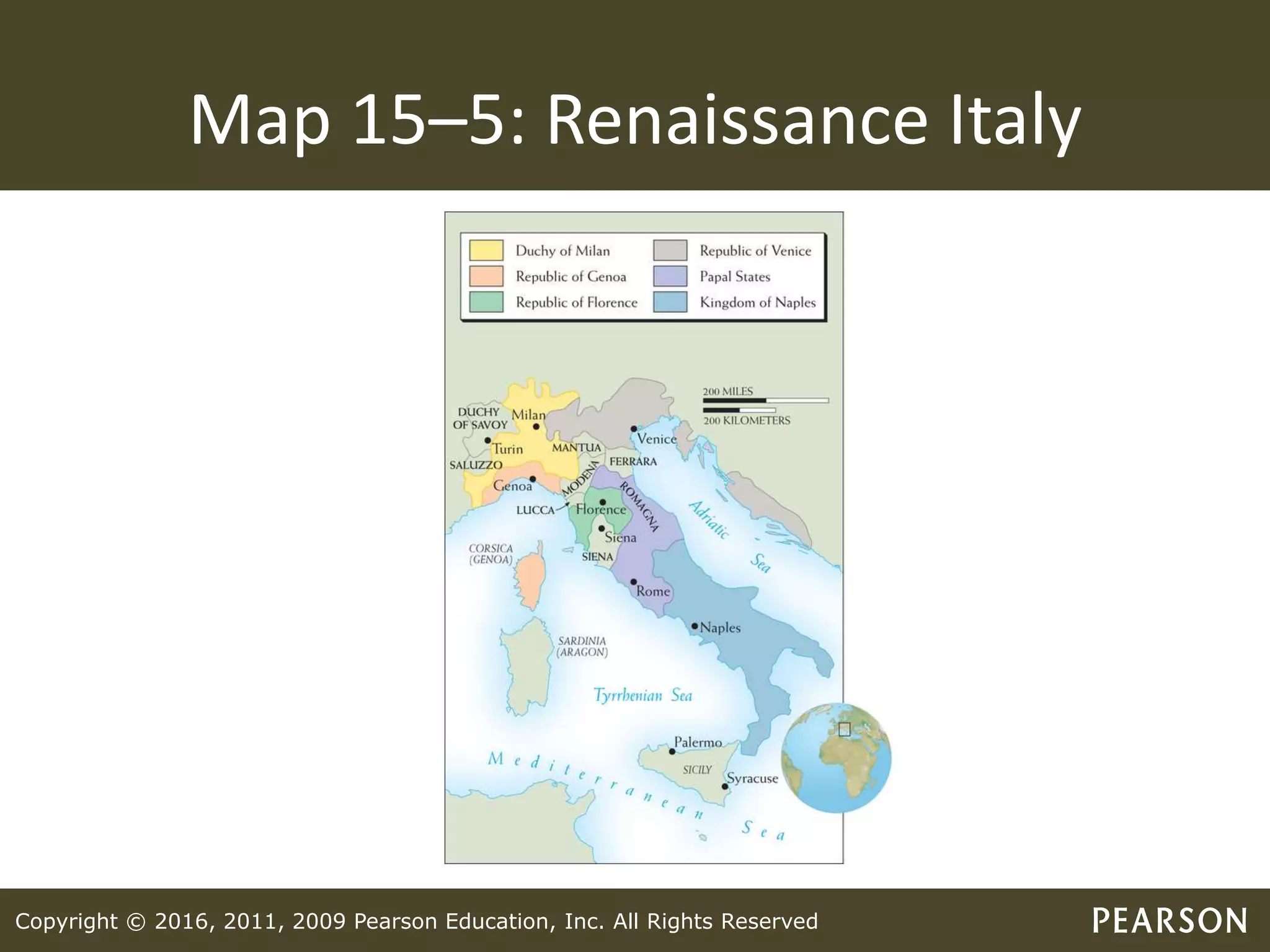

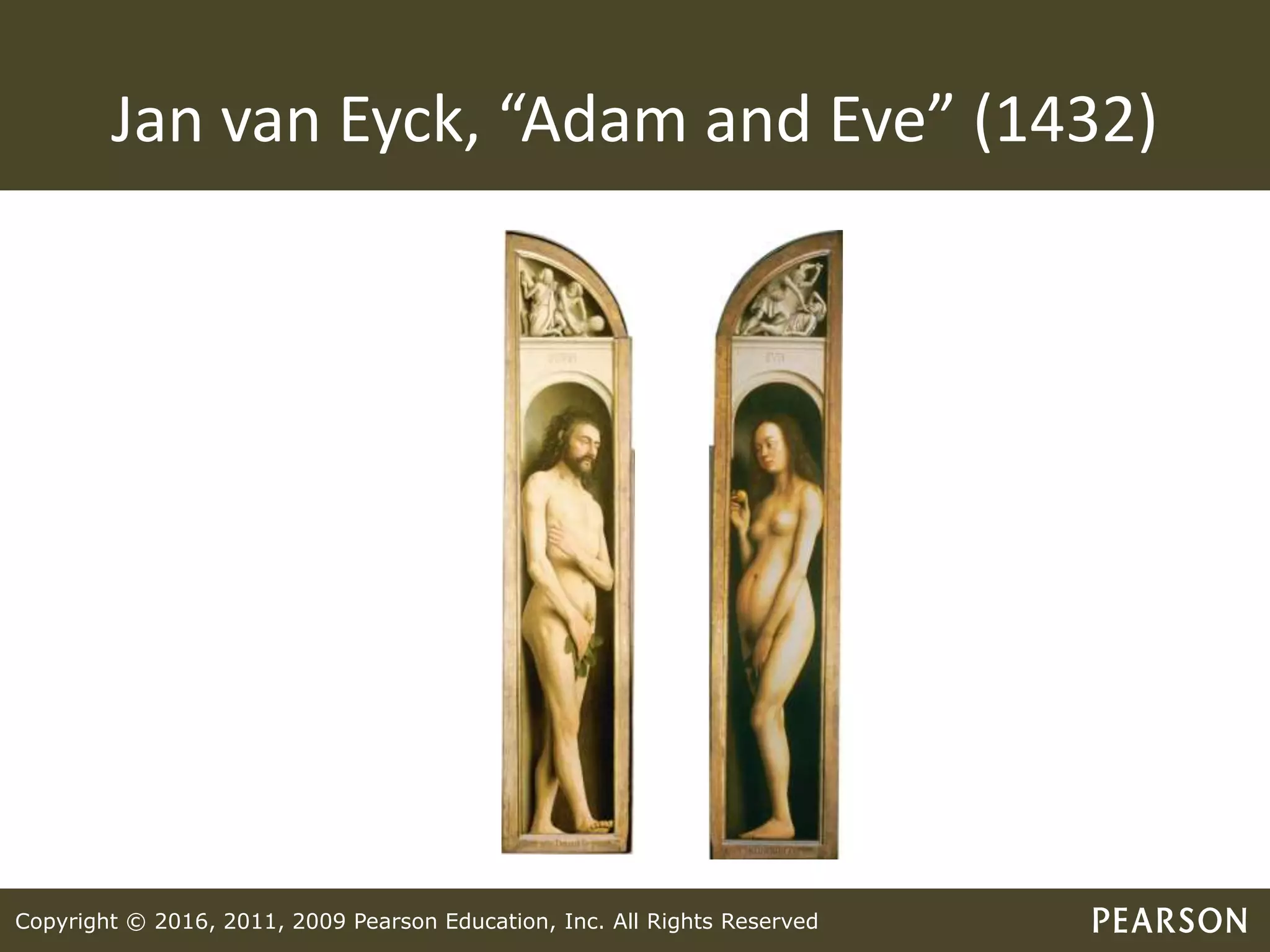

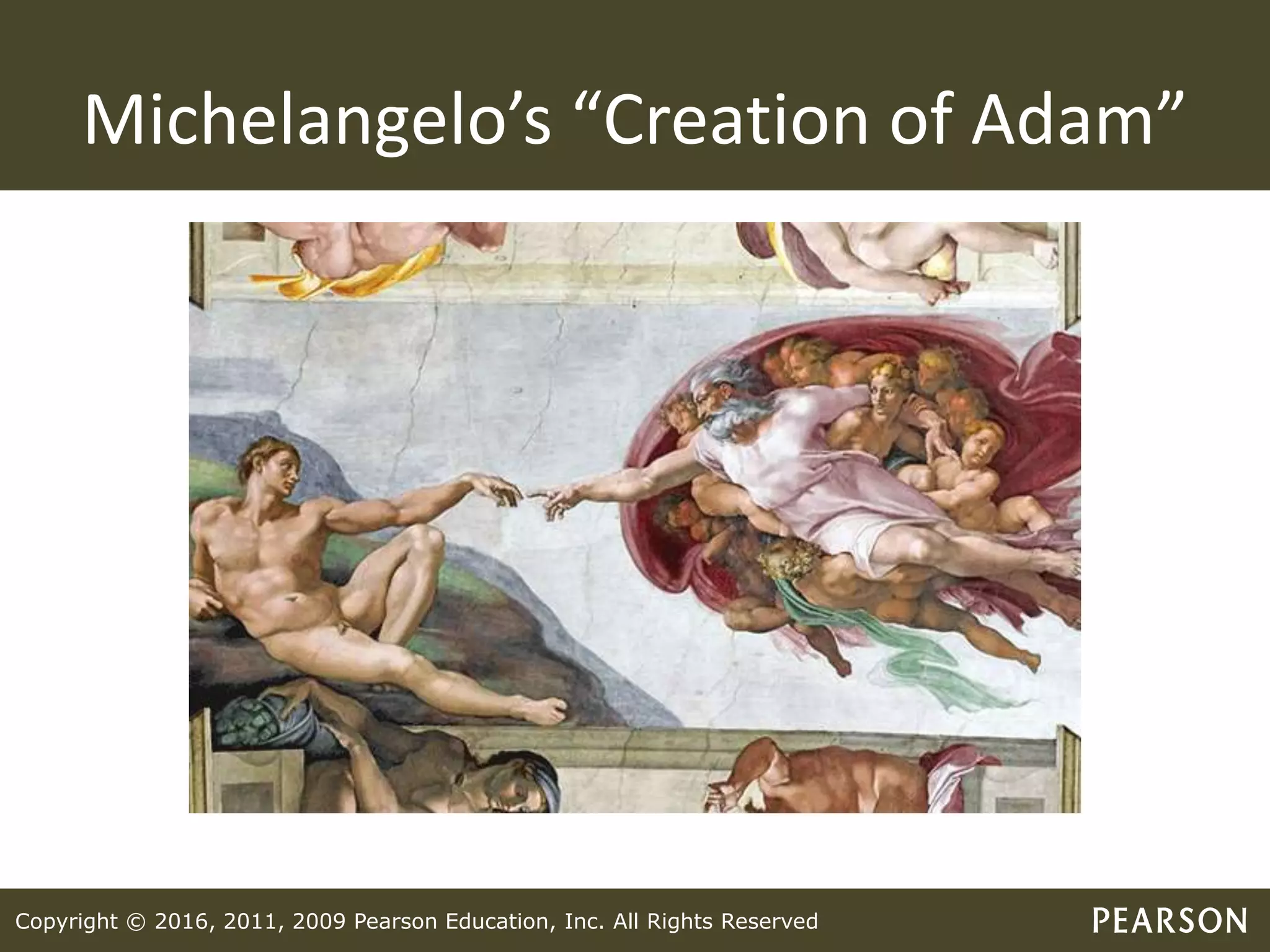

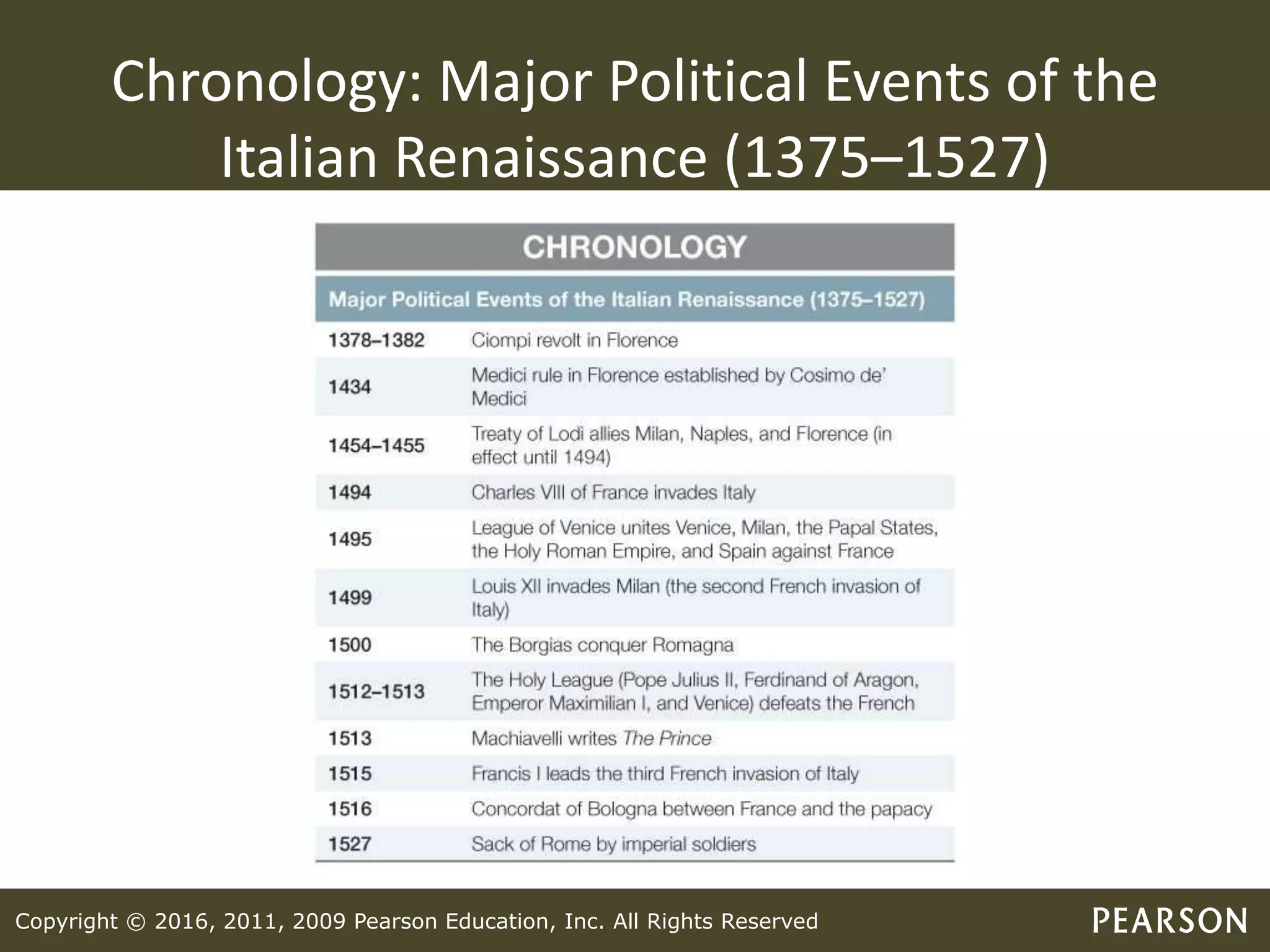

This document provides an overview of Chapter 15 from the textbook "The Heritage of World Civilizations". It discusses several topics from the High Middle Ages to the early 1500s in Europe, including the revival of the Holy Roman Empire and Catholic Church, the rise of towns, changes in medieval society, the growth of national monarchies in places like England and France, political and social breakdown during this period from events like the Hundred Years' War and Black Death pandemic, ecclesiastical issues and the Renaissance in Italy. It also includes learning objectives, introductions, summaries and maps for each section.