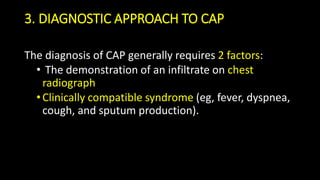

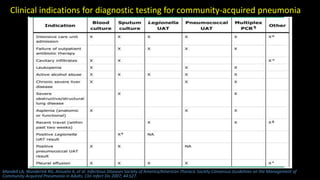

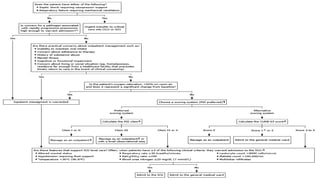

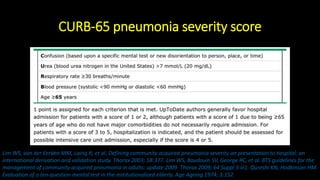

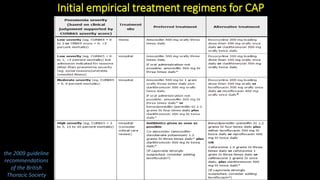

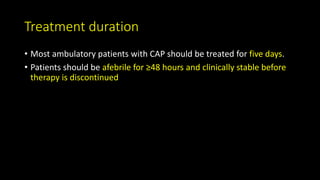

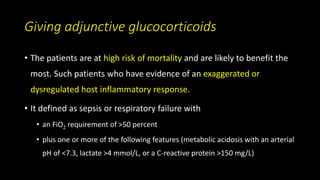

This document discusses community-acquired pneumonia (CAP). It defines CAP and outlines its epidemiology, noting risk factors like increasing age and winter season. Diagnosis involves clinical evaluation, chest imaging, and ruling out other causes if imaging is abnormal but symptoms aren't. Severity is assessed using scores like CURB-65 to determine appropriate treatment setting. Most ambulatory patients receive 5 days of antibiotics while hospitalized patients get broader empiric coverage. Adjunctive steroids may benefit severe cases. Proper follow up and prevention through vaccination and smoking cessation are also discussed.

![2. EPIDERMIOLOGY

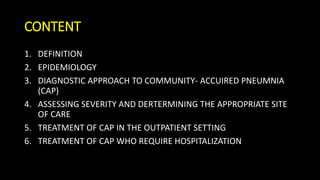

• The incidence of CAP is approximately 5.16 to 6.11 cases per 1000 persons

per year in US. The rate of CAP increases with increasing age. [1]

• More cases occurring during the winter months

• Men > women; black persons > Caucasians

• The etiology of CAP varies by geographic region; however, Streptococcus

pneumoniae is the most commonly identified bacterial cause of CAP

worldwide. Viruses are common causes of CAP as well [2], [3]

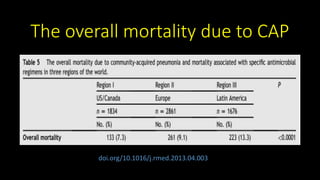

• All-cause mortality in patients with CAP is as high as 28 percent within one

year.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/community-acquiredpneumoniacap-180604133440/85/Community-acquired-pneumonia-cap-4-320.jpg)

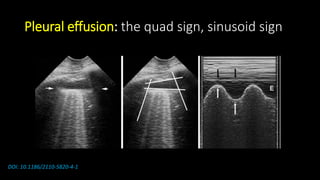

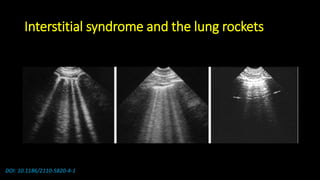

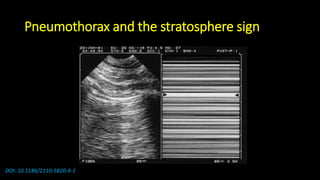

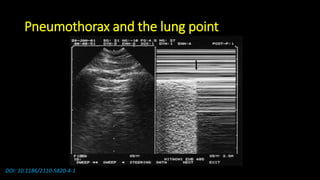

![Some notices

• Lung ultrasound to diagnose pneumonia with the

sensitivity of lung ultrasound was approximately 80 to

90 percent and the specificity approximately 70 to 90

percent. [4], [5]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/community-acquiredpneumoniacap-180604133440/85/Community-acquired-pneumonia-cap-17-320.jpg)

![Reference

• [1] Marrie TJ, Huang JQ. Epidemiology of community-acquired pneumonia in Edmonton, Alberta: an emergency department-based

study. Can Respir J 2005; 12:139.

• [2] Gadsby NJ, Russell CD, McHugh MP, et al. Comprehensive Molecular Testing for Respiratory Pathogens in Community-Acquired

Pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62:817.

• [3] Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al. Community-Acquired Pneumonia Requiring Hospitalization among U.S. Adults. N Engl J

Med 2015; 373:415.

• [4] Long L, Zhao HT, Zhang ZY, et al. Lung ultrasound for the diagnosis of pneumonia in adults: A meta-analysis. Medicine

(Baltimore) 2017; 96:e5713.

• [5] Llamas-Álvarez AM, Tenza-Lozano EM, Latour-Pérez J. Accuracy of Lung Ultrasonography in the Diagnosis of Pneumonia in

Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Chest 2017; 151:374.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/community-acquiredpneumoniacap-180604133440/85/Community-acquired-pneumonia-cap-58-320.jpg)

![[6] Treatment of community-acquired pneumonia in adults who require hospitalization, Thomas M File, Jr, MD

[7] Community-acquired pneumonia in adults: Assessing severity and determining the appropriate site of care,

Donald M Yealy, MD, FACEP, Michael J Fine, MD, MSc

[8] Diagnostic approach to community-acquired pneumonia in adults, John G Bartlett, MD

[9] Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and microbiology of community-acquired pneumonia in adults, Thomas J

Marrie, MD, Thomas M File, Jr, MD

[10] Treatment of community-acquired pneumonia in adults in the outpatient setting, Thomas M File, Jr, MD](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/community-acquiredpneumoniacap-180604133440/85/Community-acquired-pneumonia-cap-59-320.jpg)