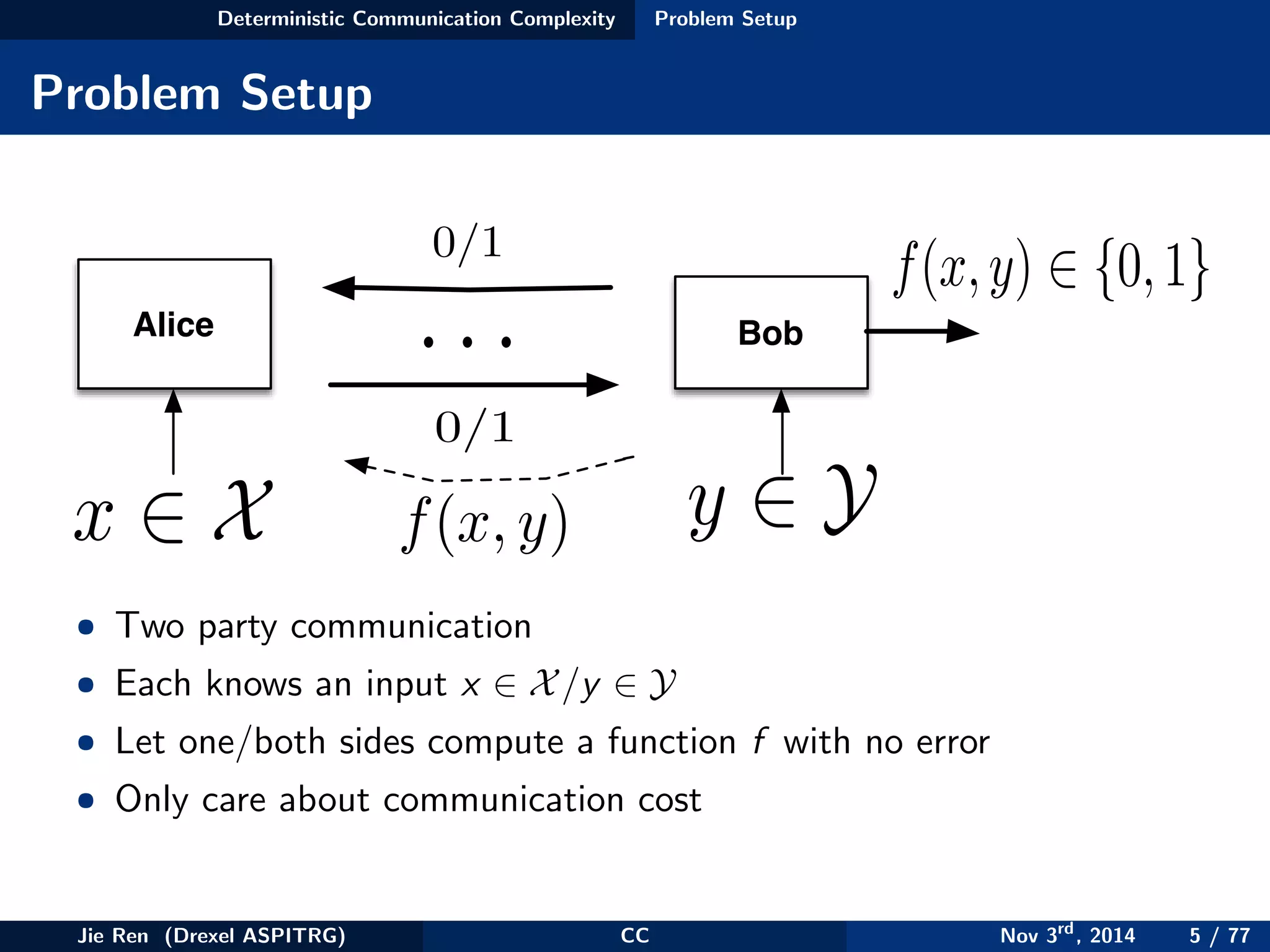

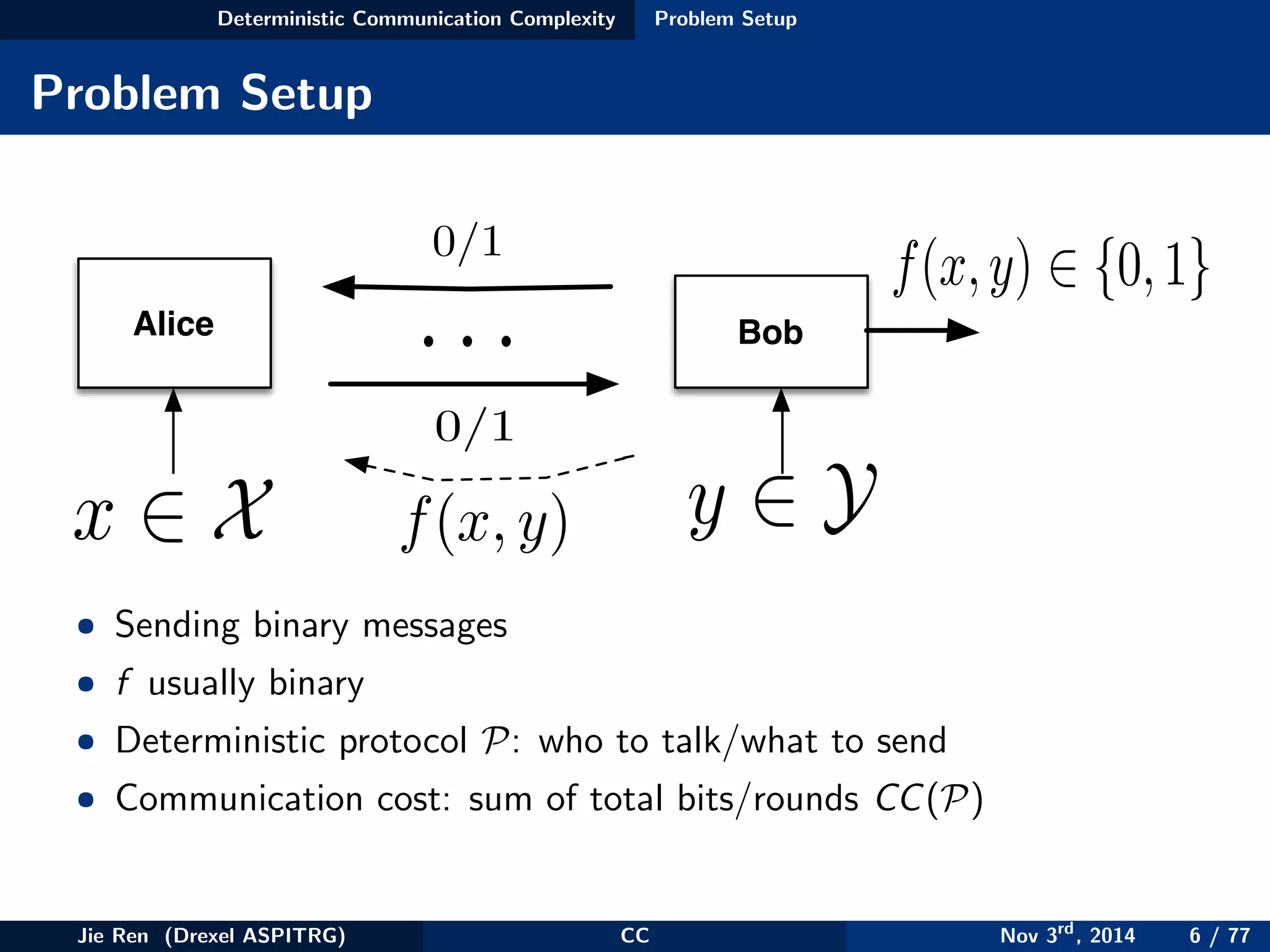

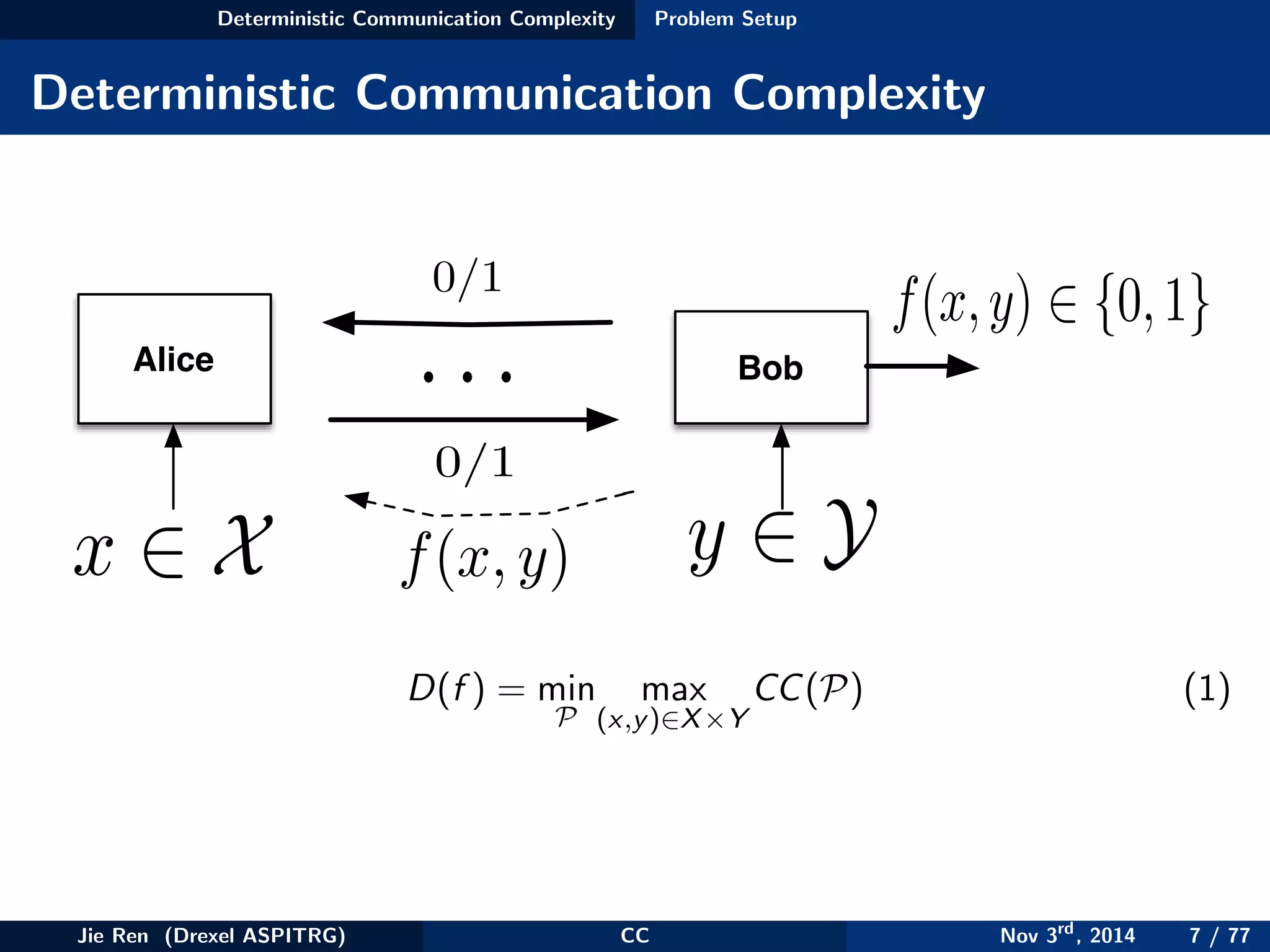

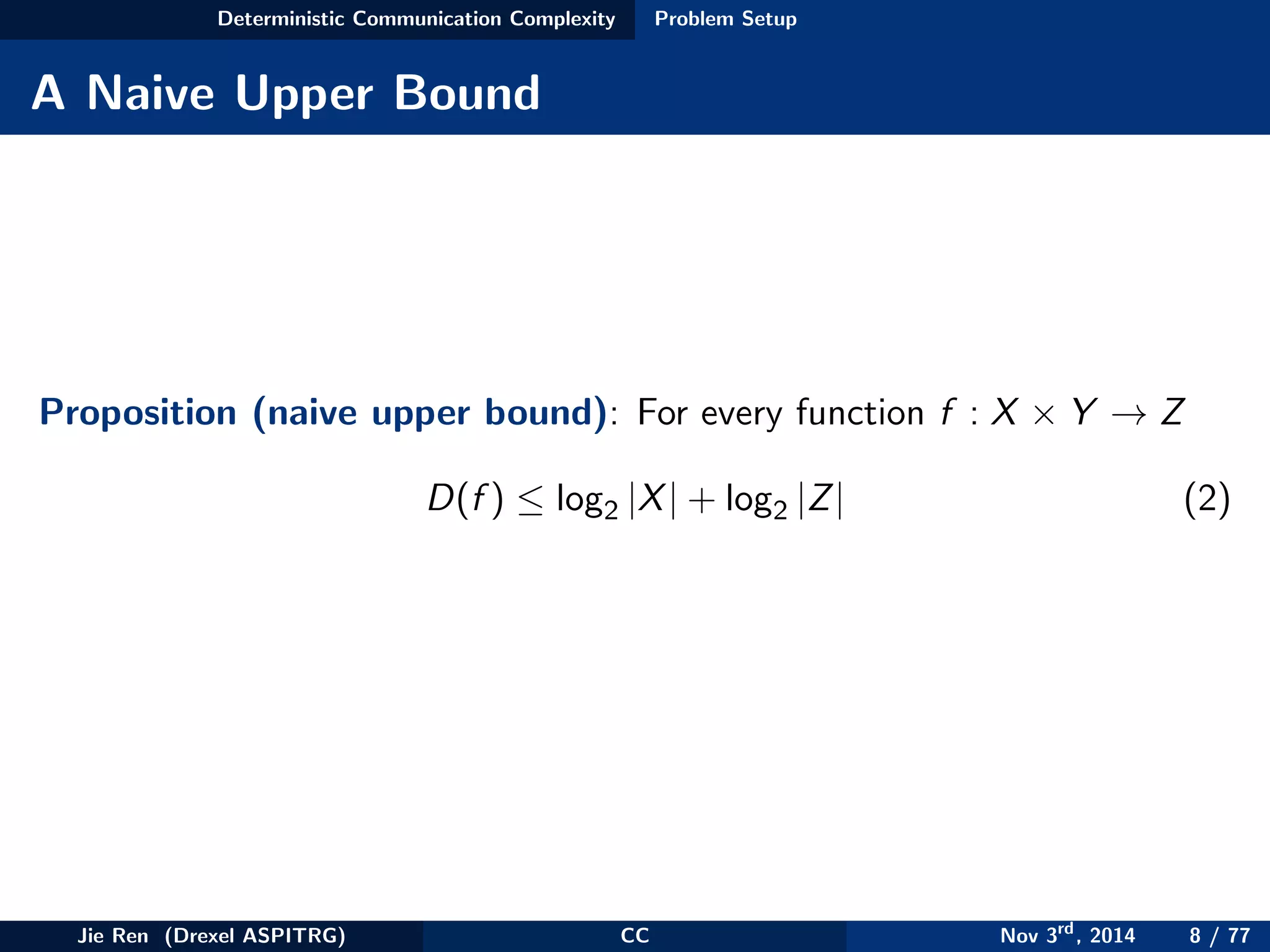

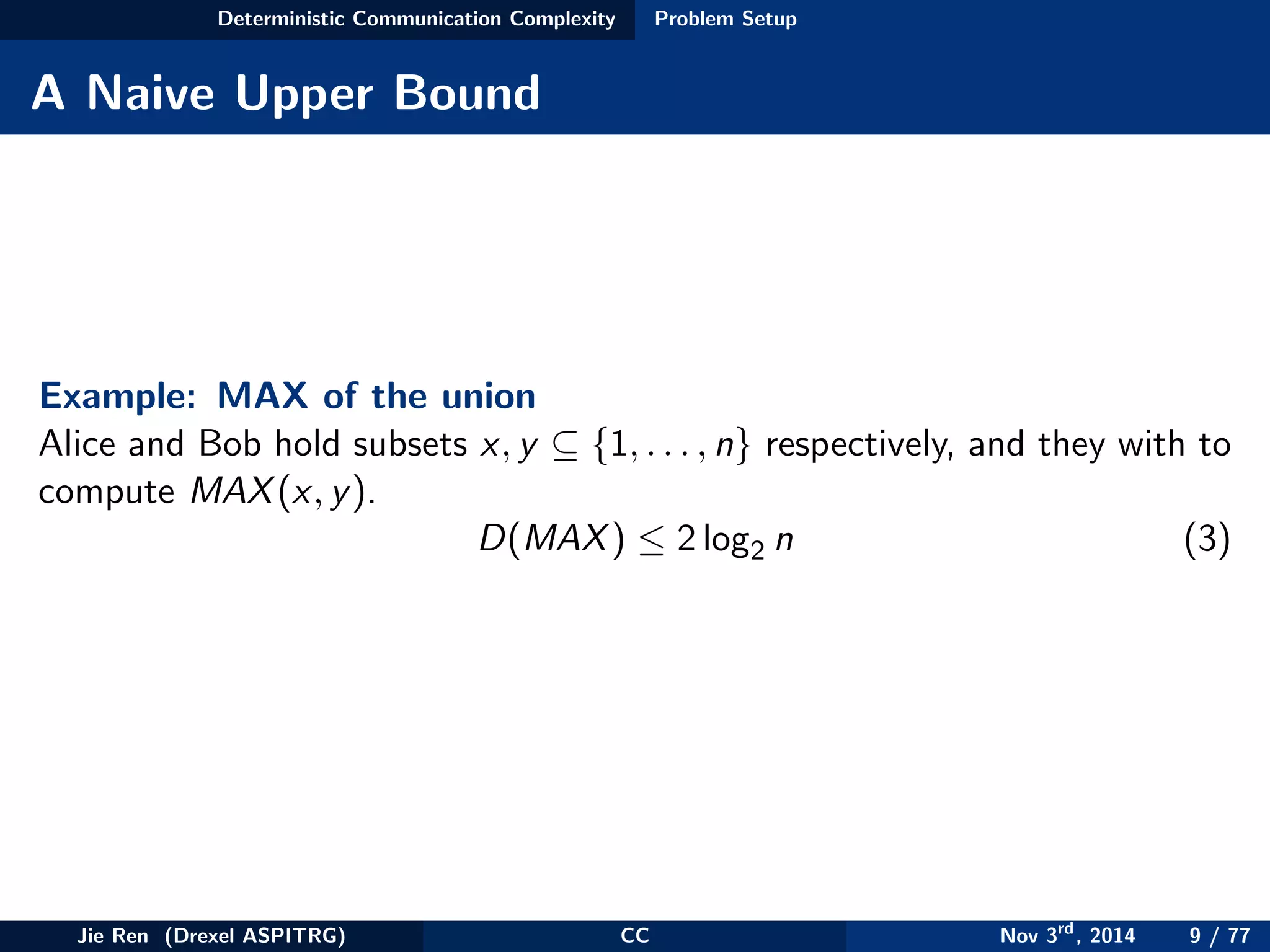

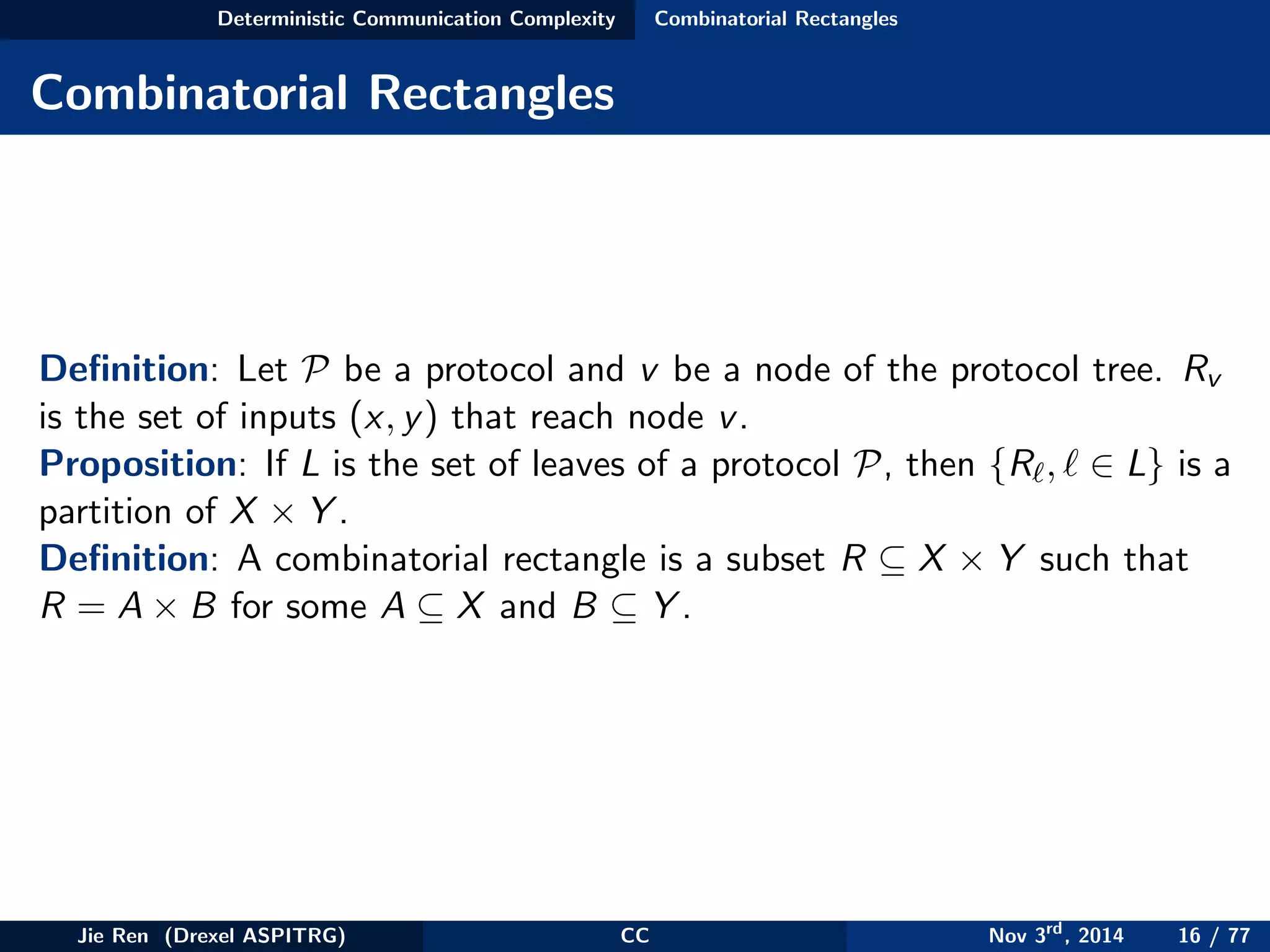

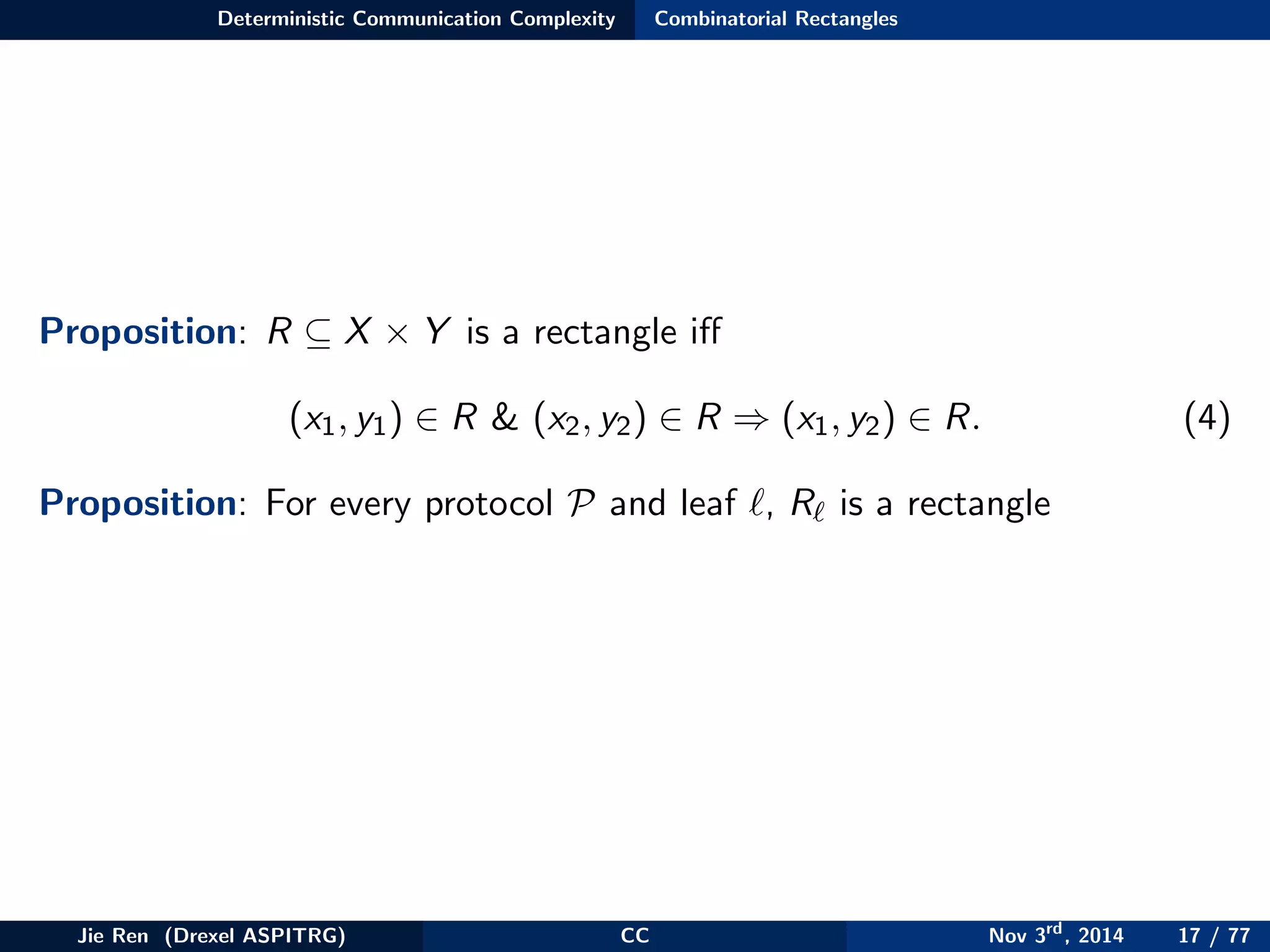

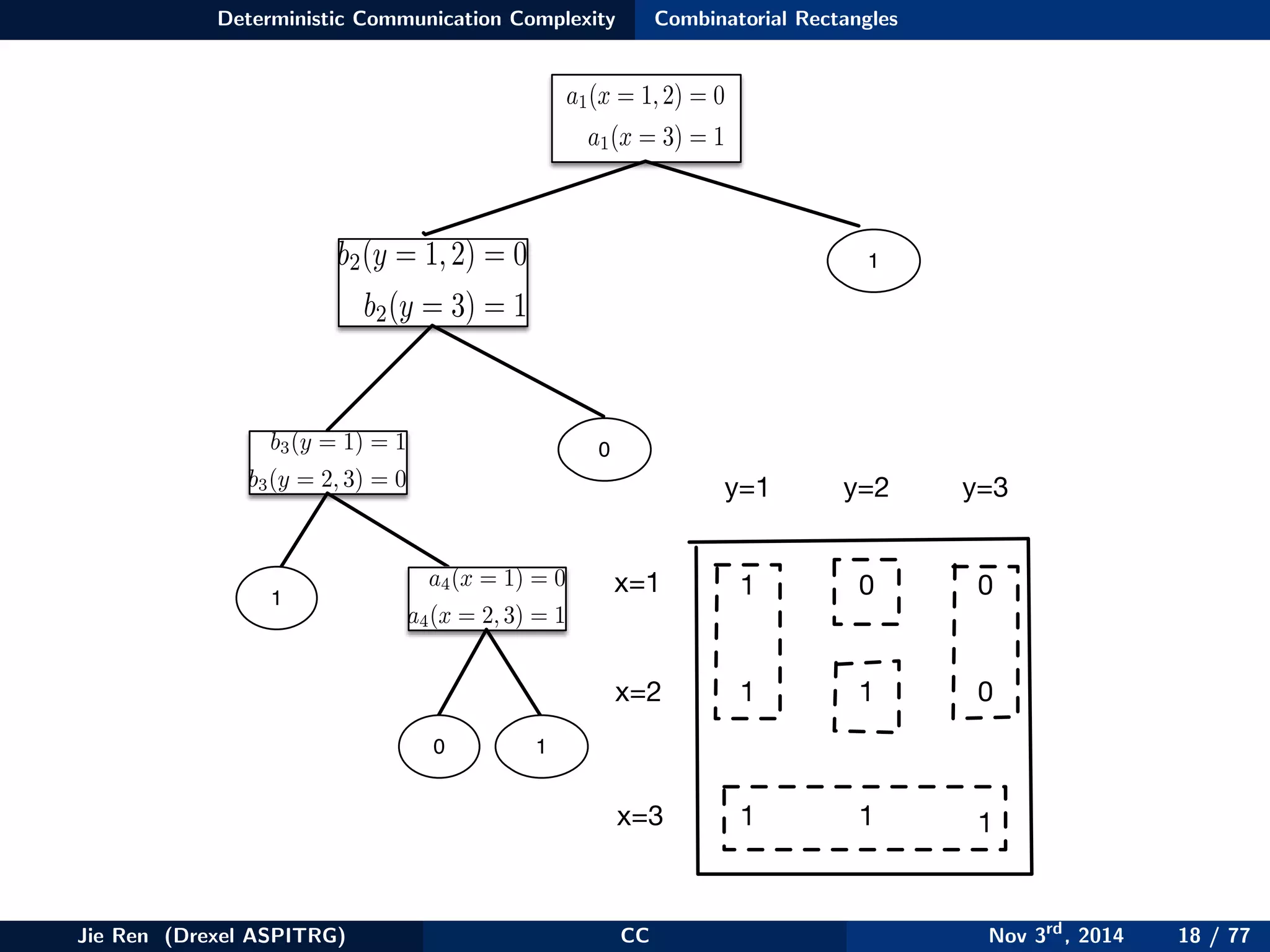

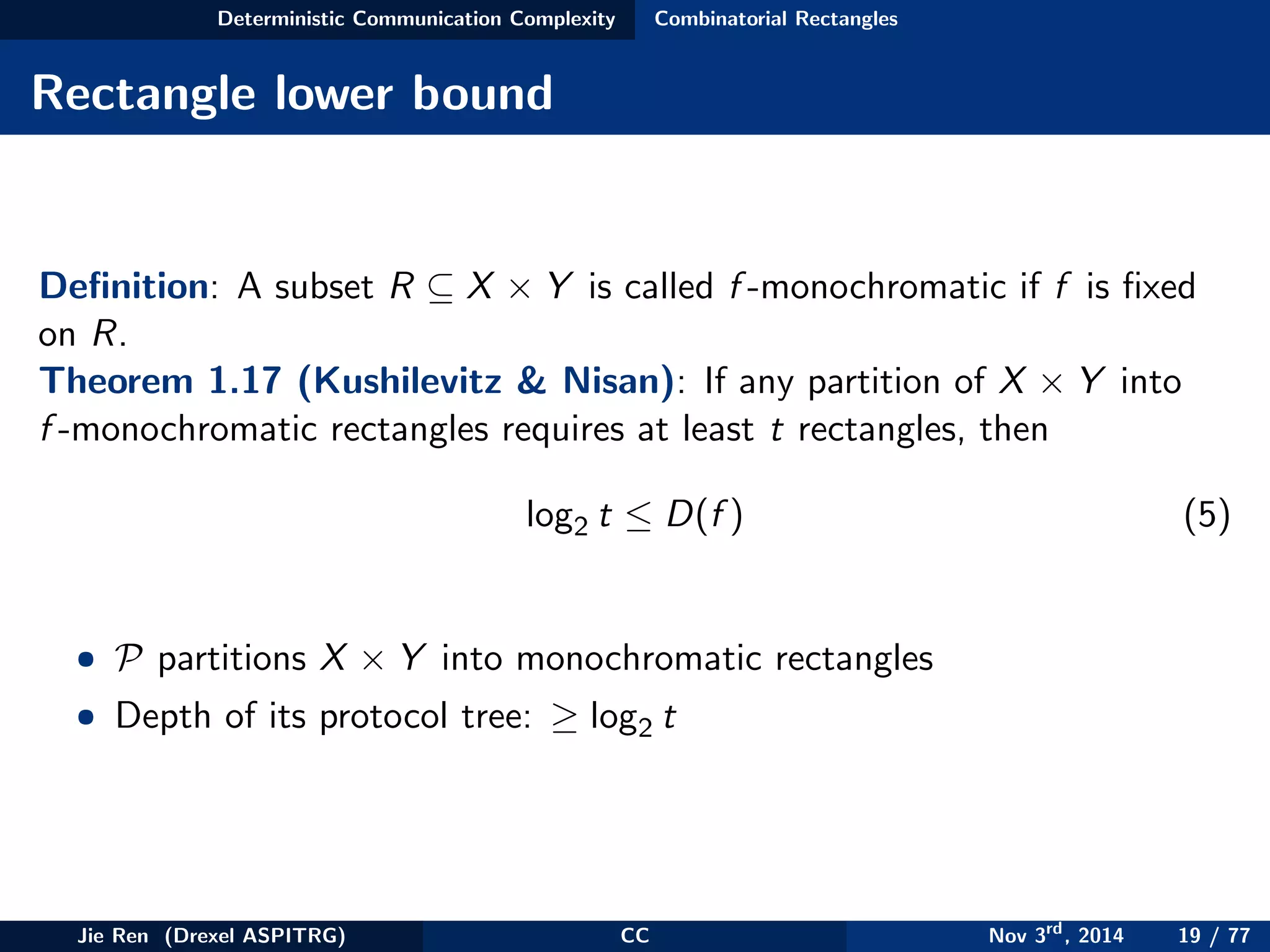

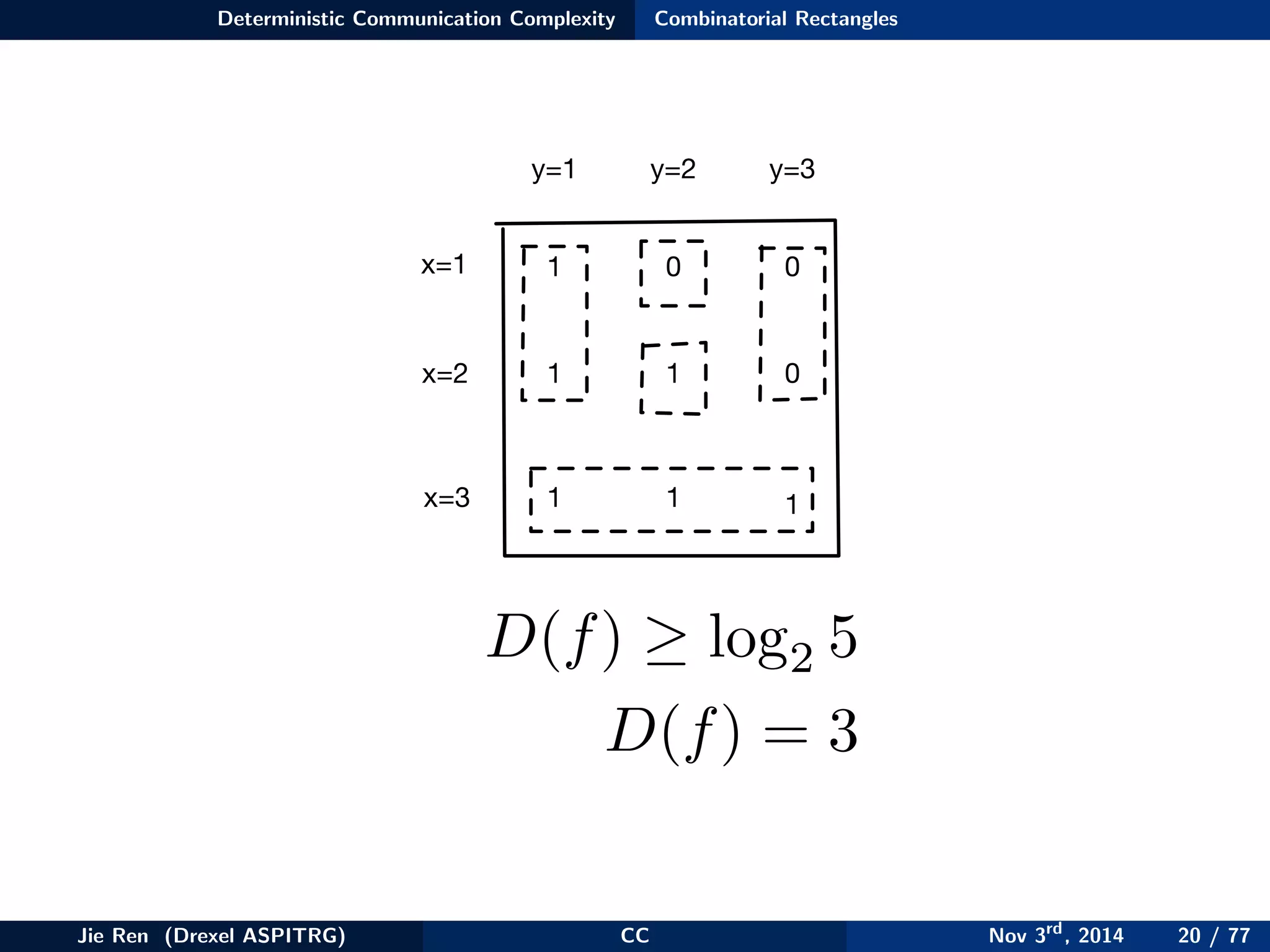

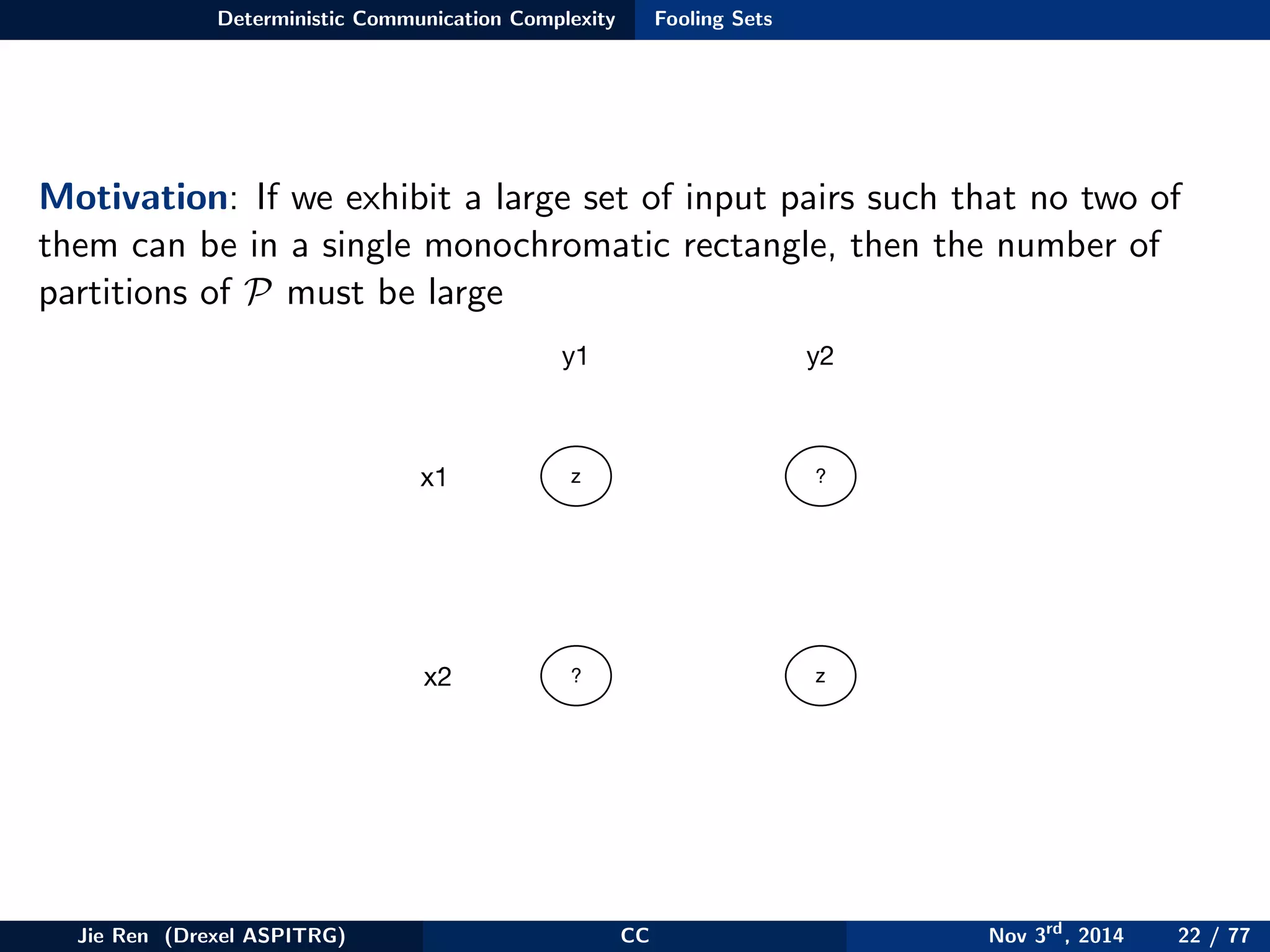

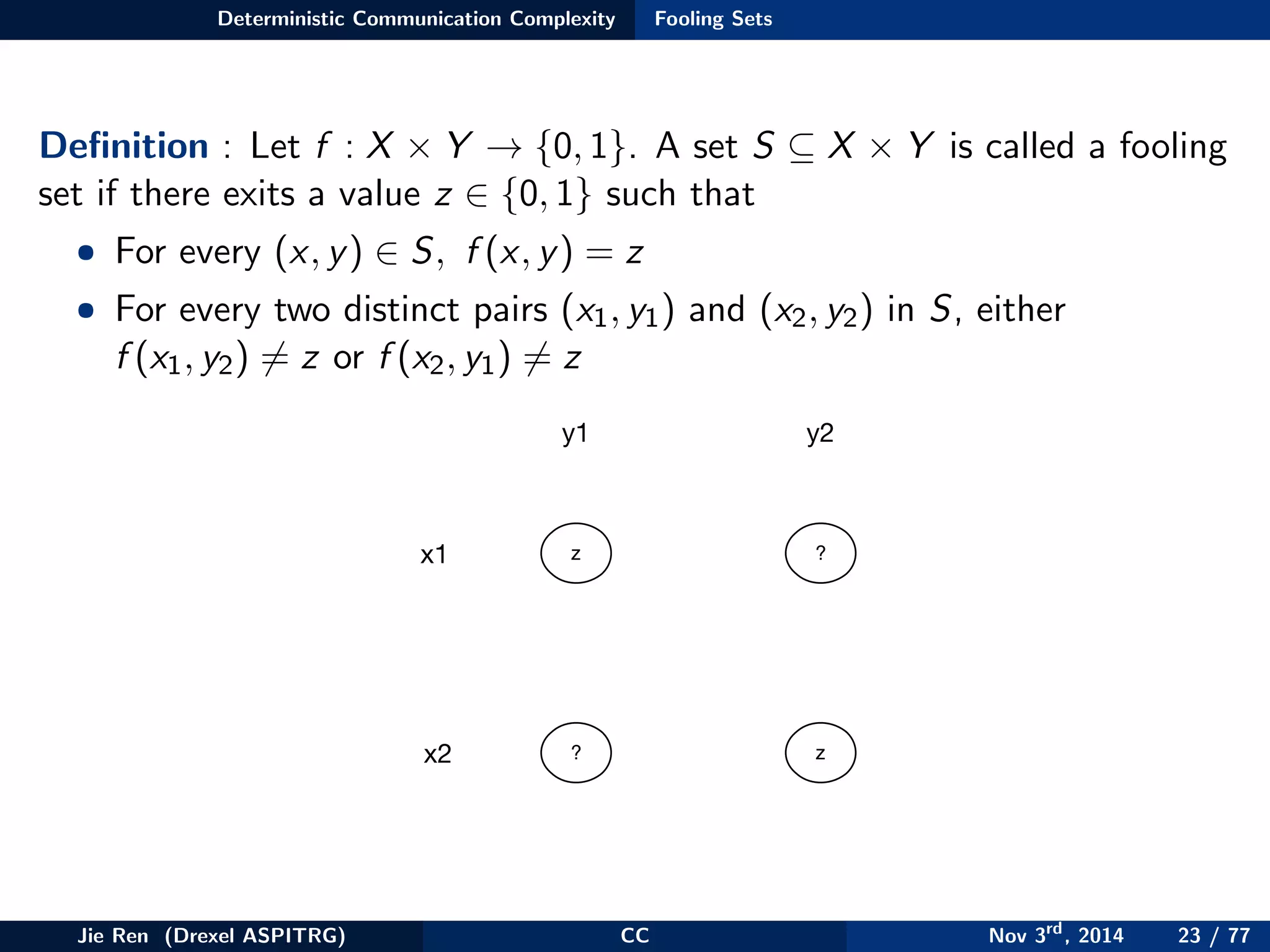

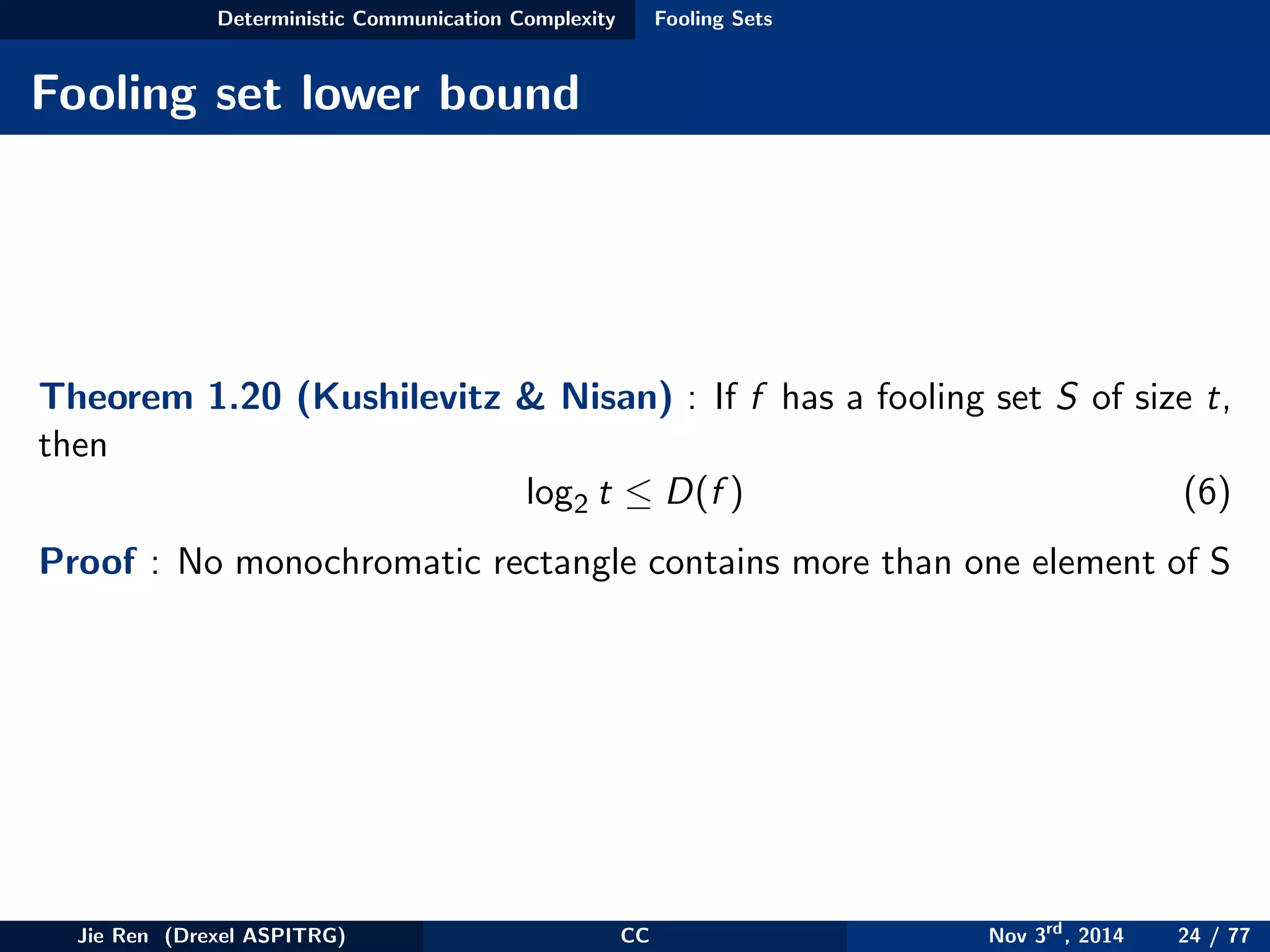

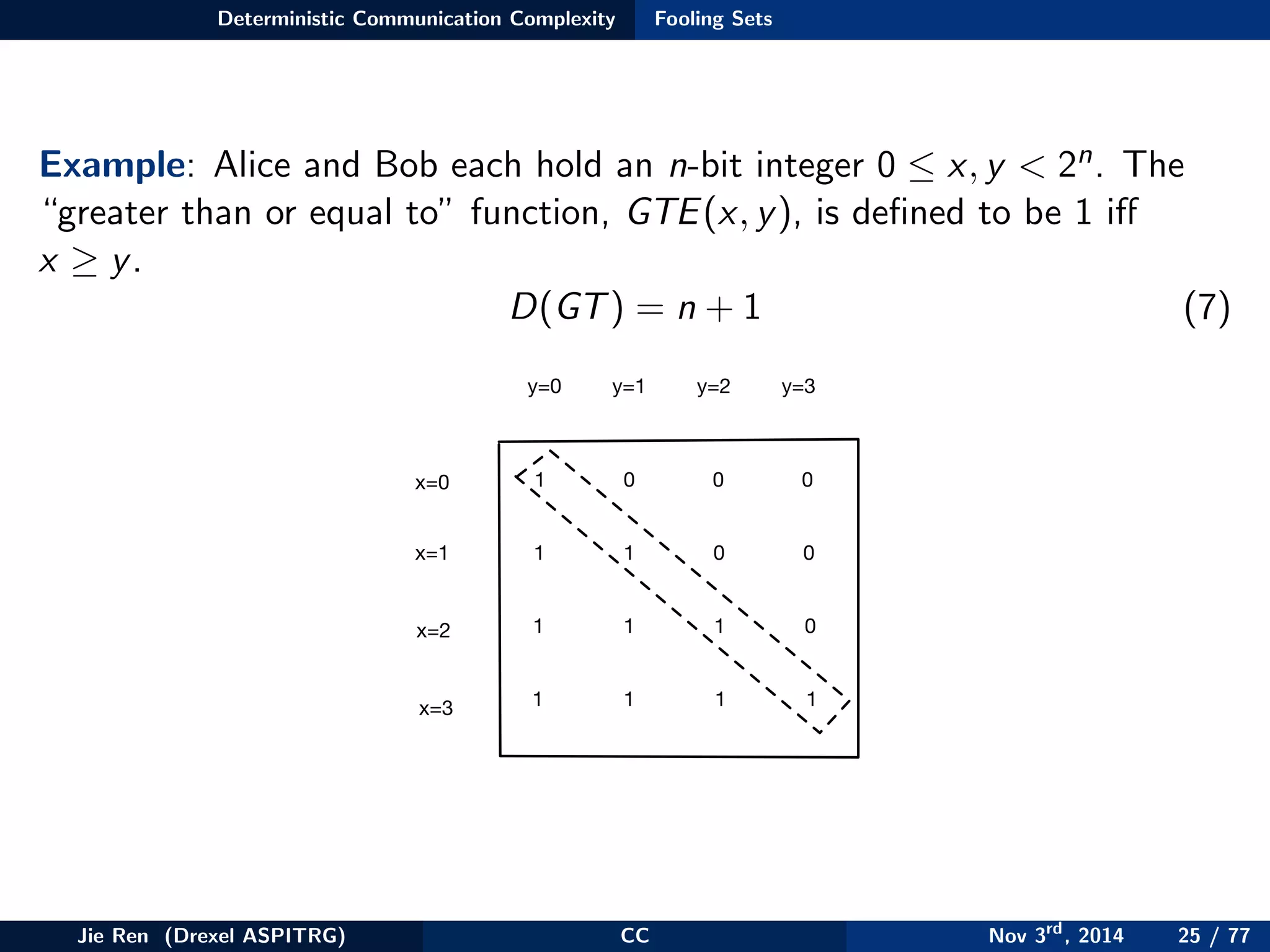

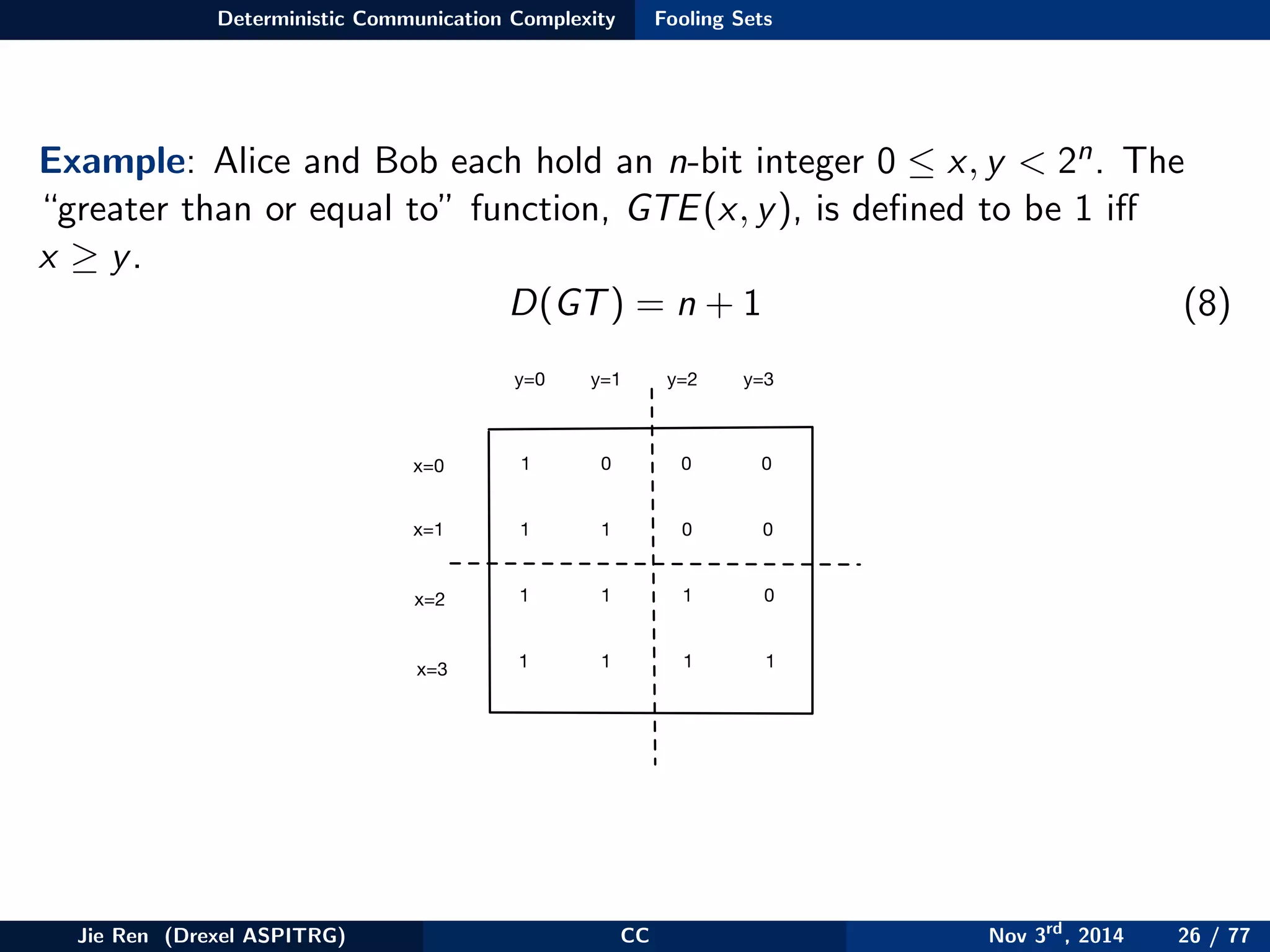

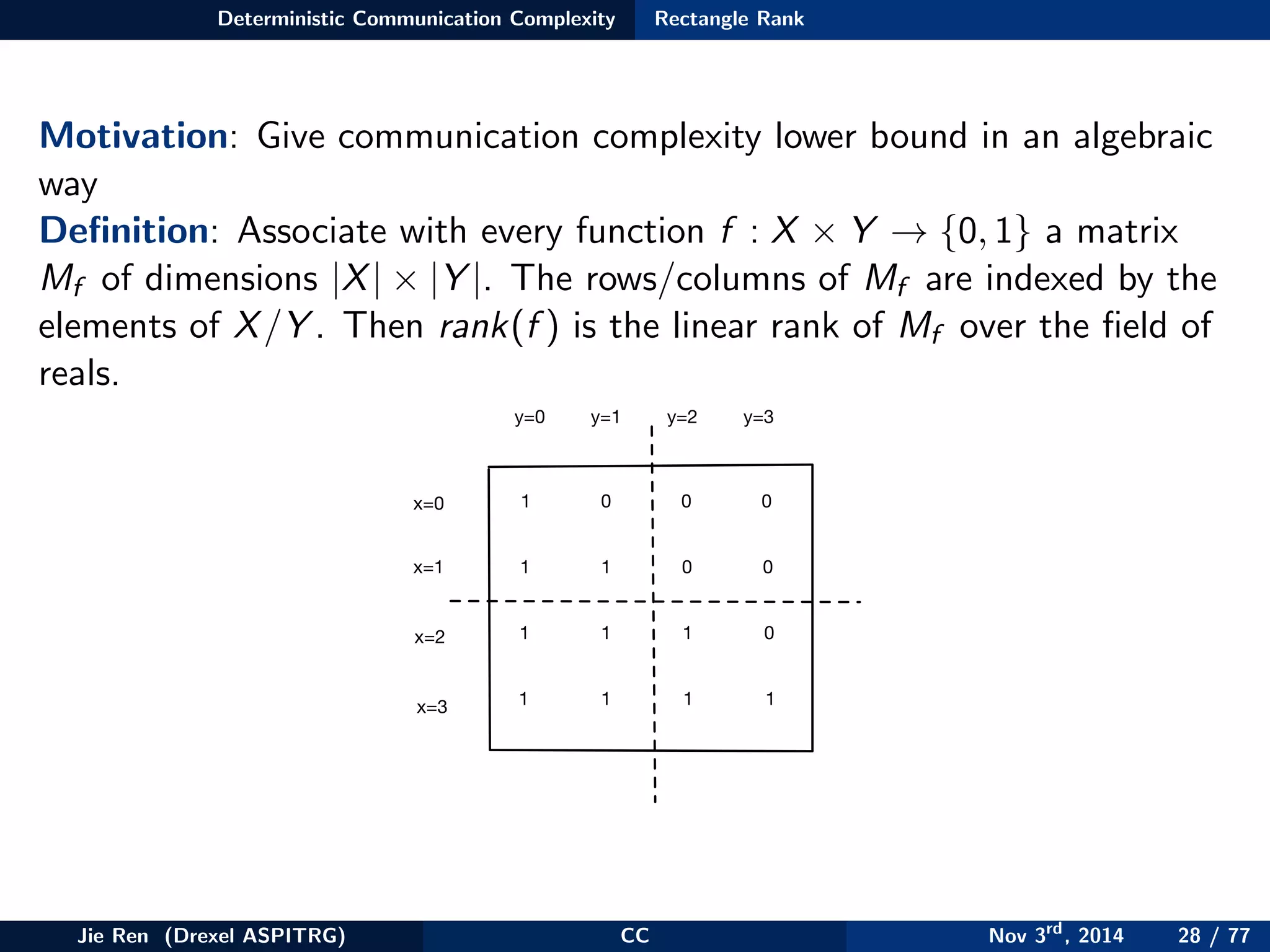

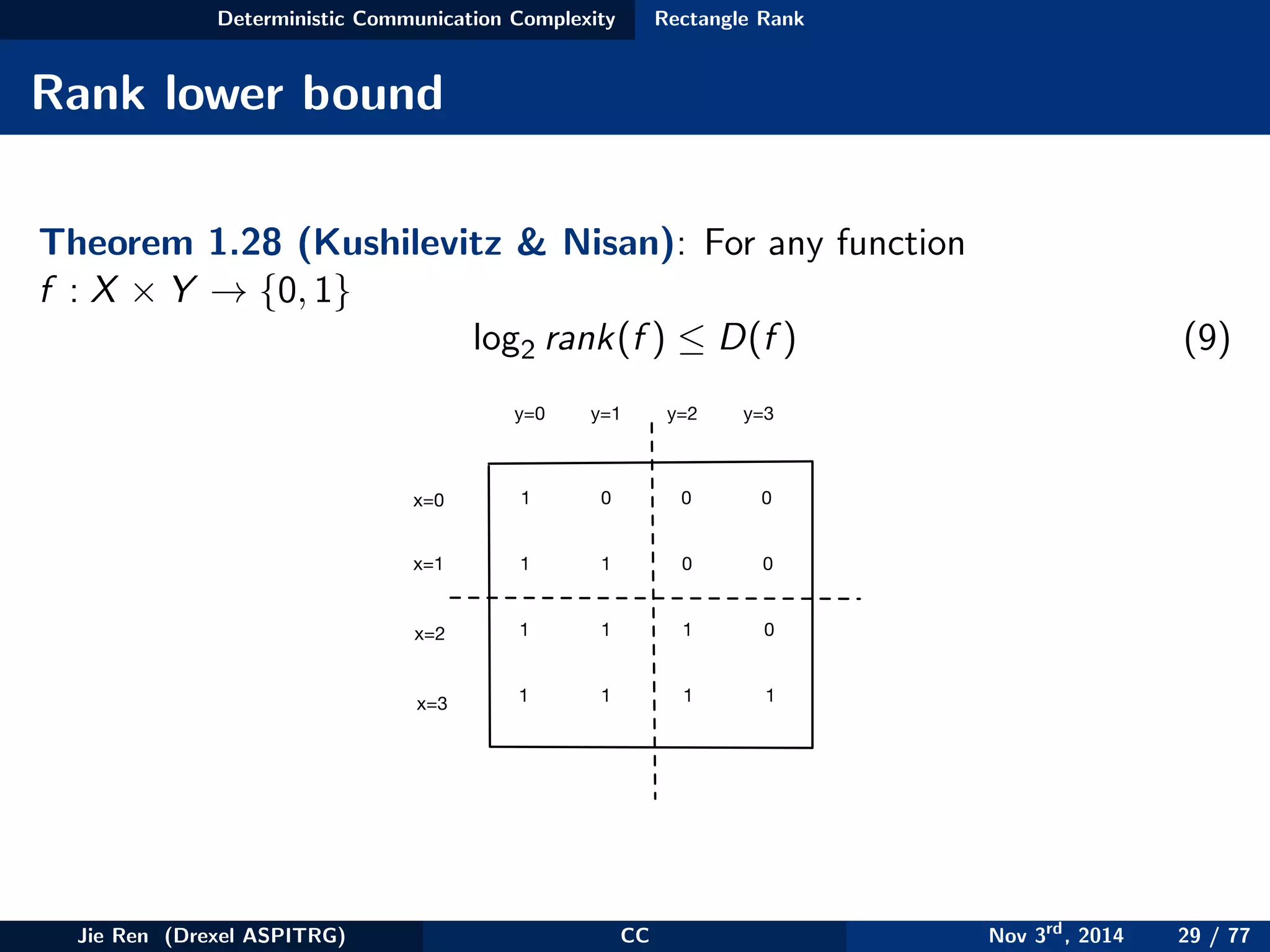

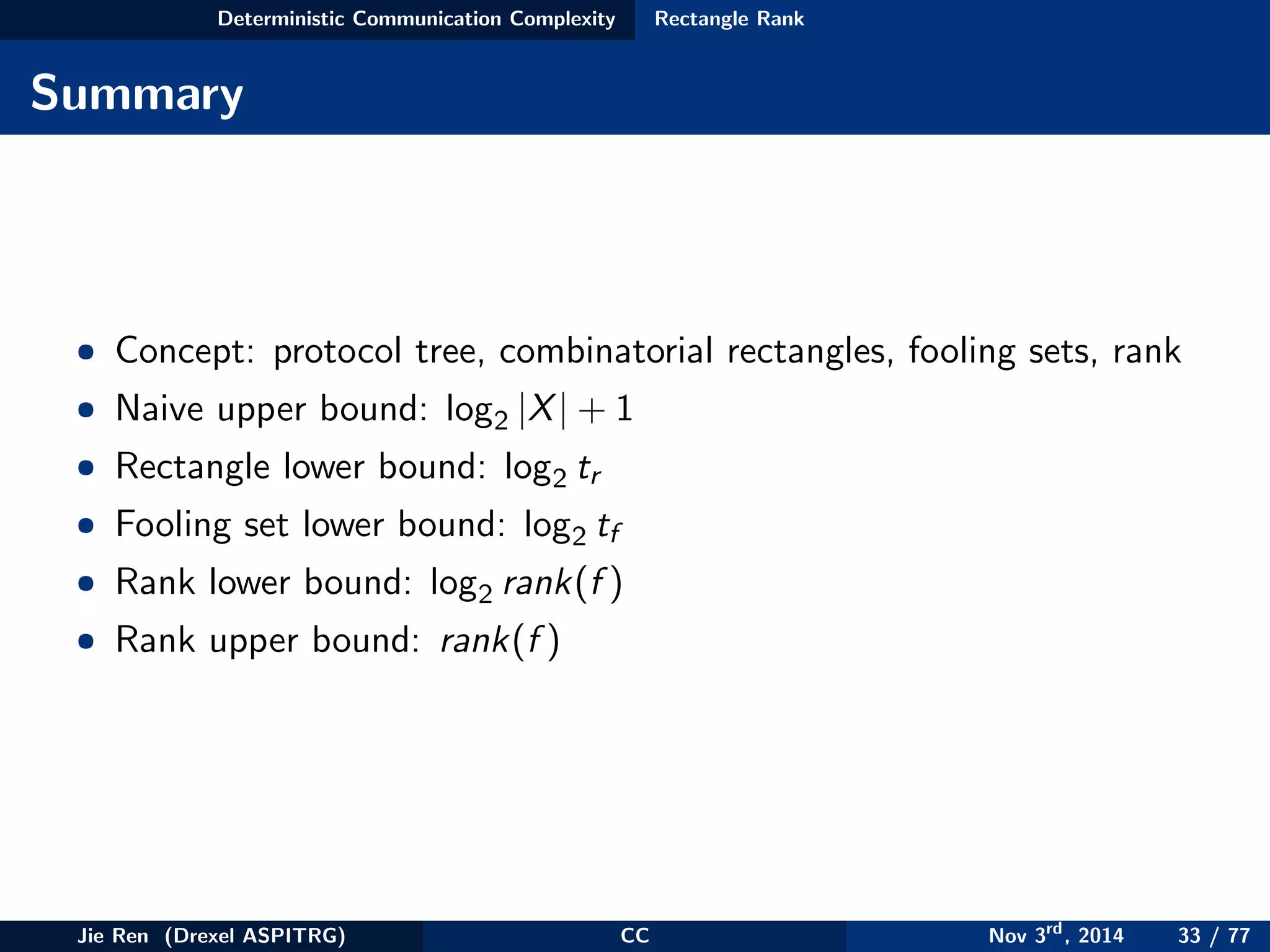

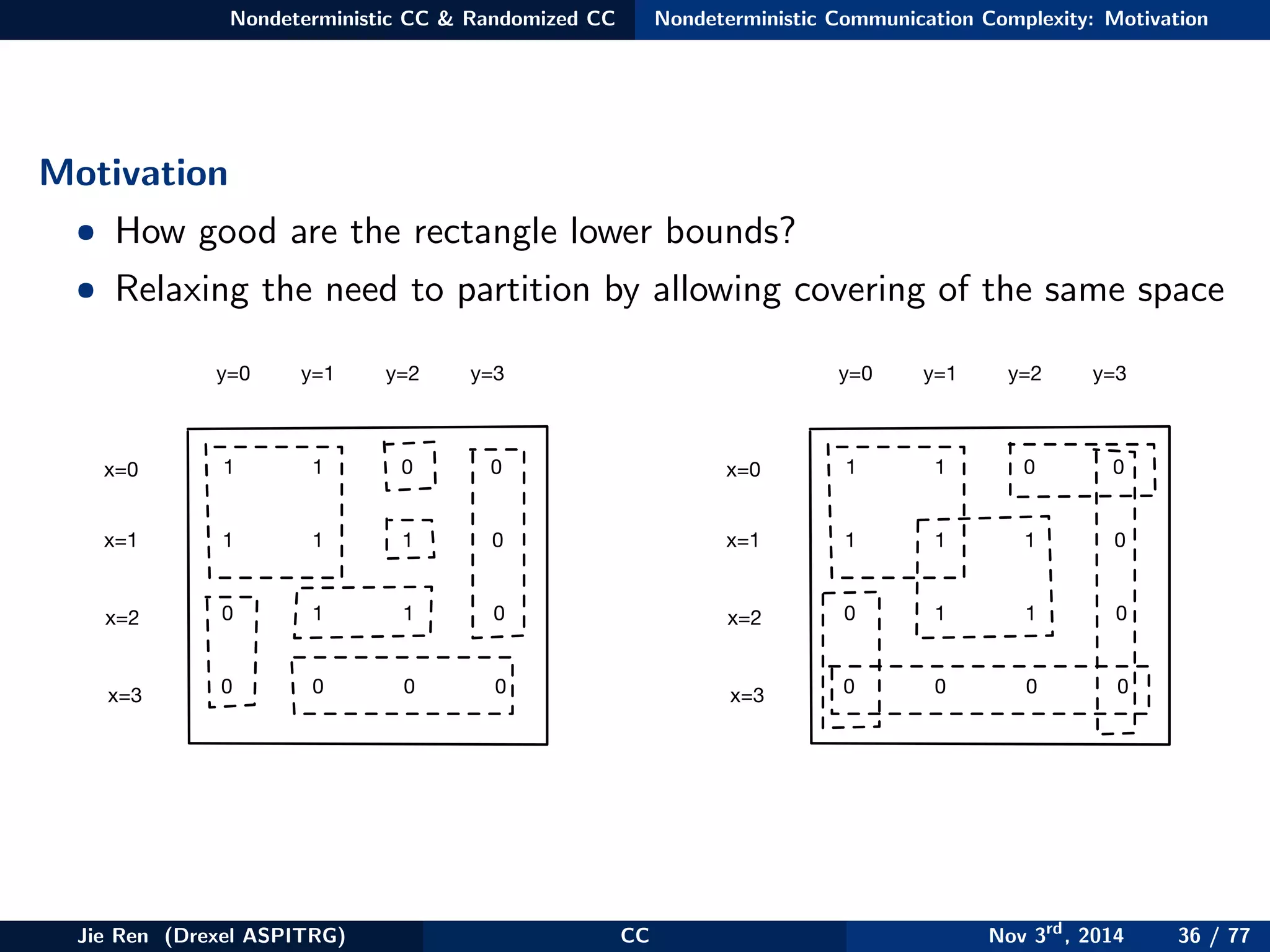

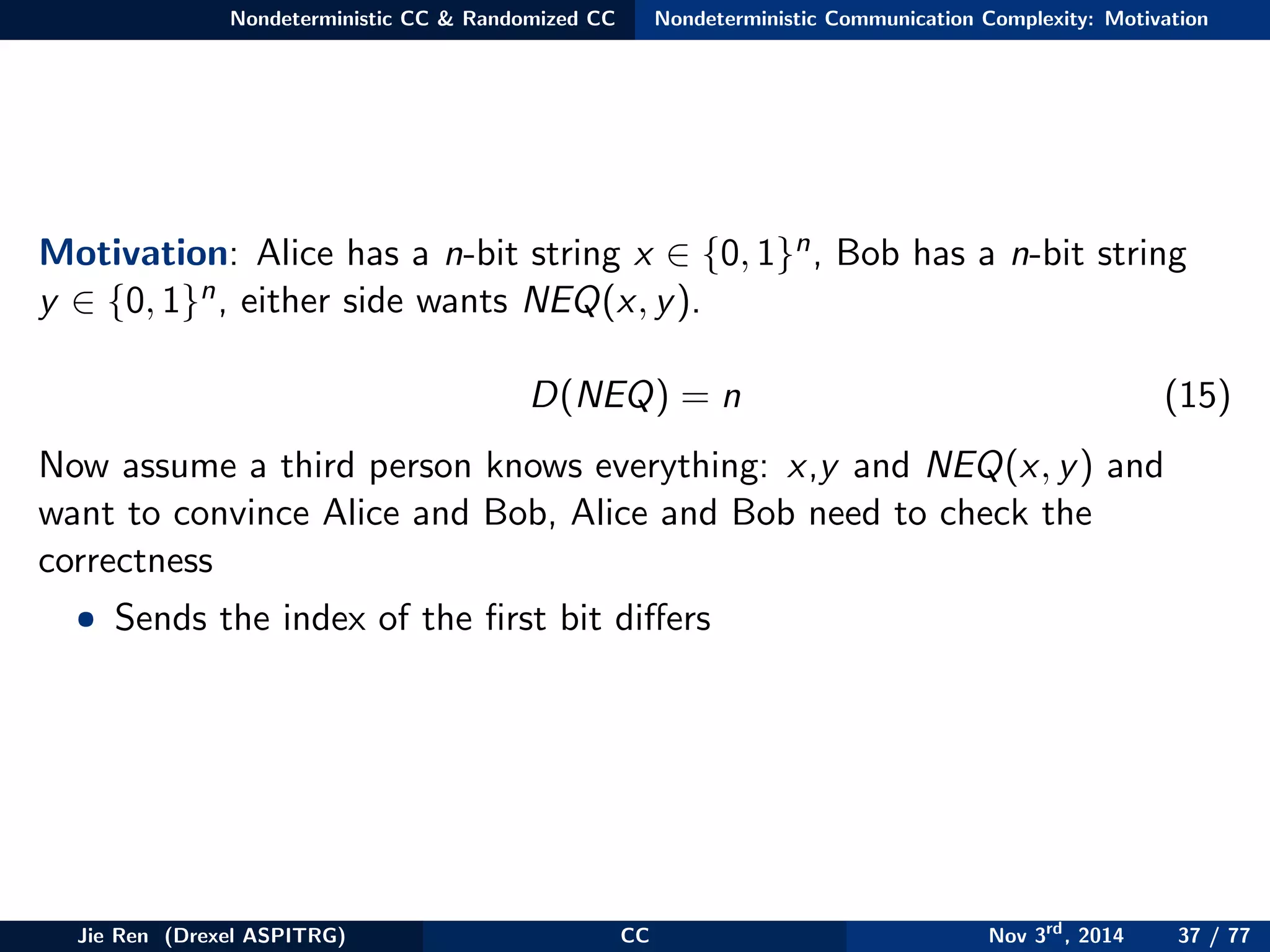

This document provides an overview of communication complexity and deterministic communication complexity. It begins with defining the problem setup, which involves two parties (Alice and Bob) trying to compute a function f based on their private inputs using the minimum communication. It then discusses protocol trees, which model communication protocols, and shows they partition the input space into rectangles. It introduces combinatorial rectangles and shows how the minimum number of rectangles needed to partition the space can provide a lower bound on communication complexity. The document also discusses fooling sets, another technique to lower bound communication complexity, and previews upcoming topics on nondeterministic and randomized communication complexity.

![Nondeterministic CC & Randomized CC Randomized Communication Complexity

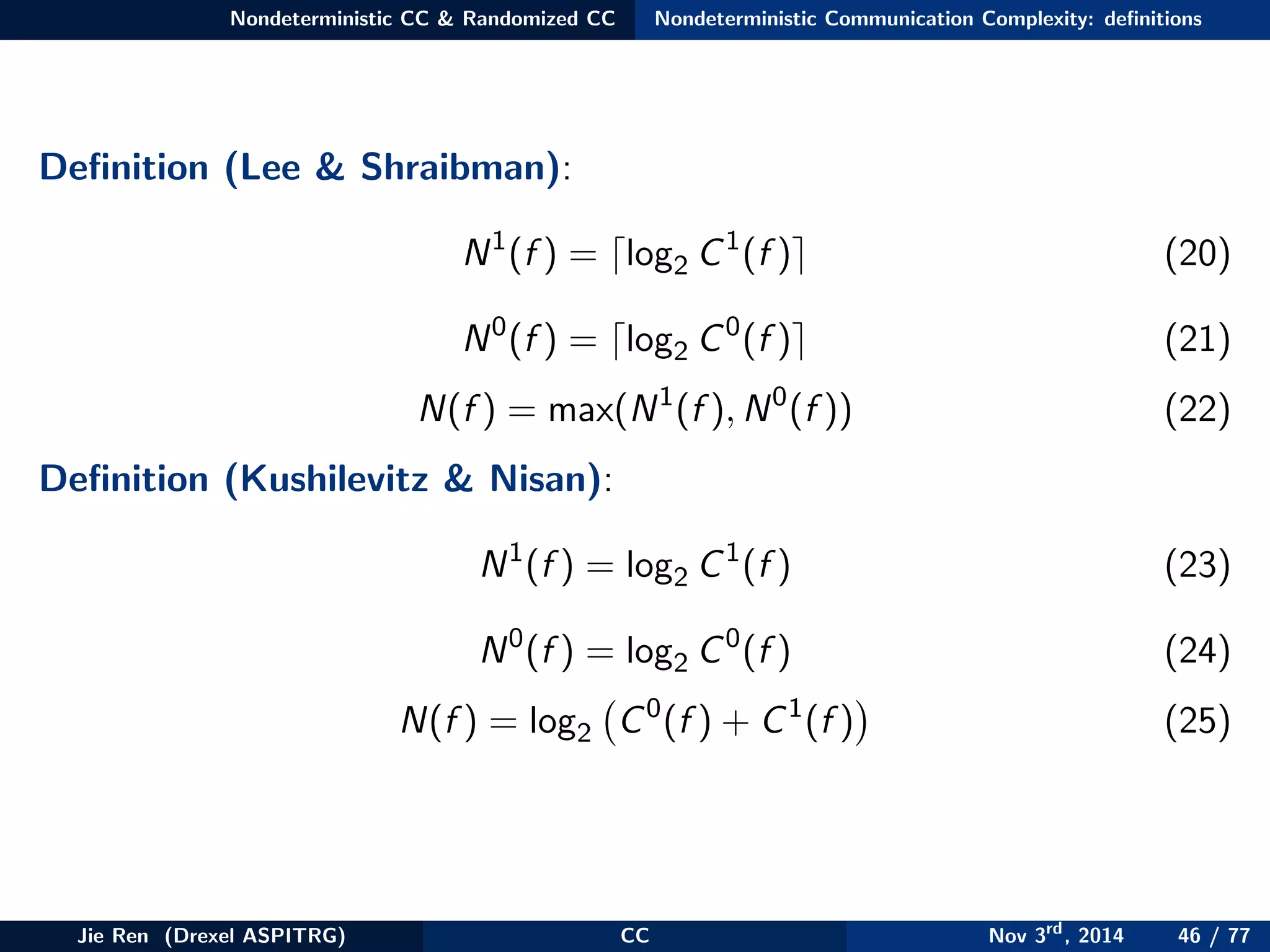

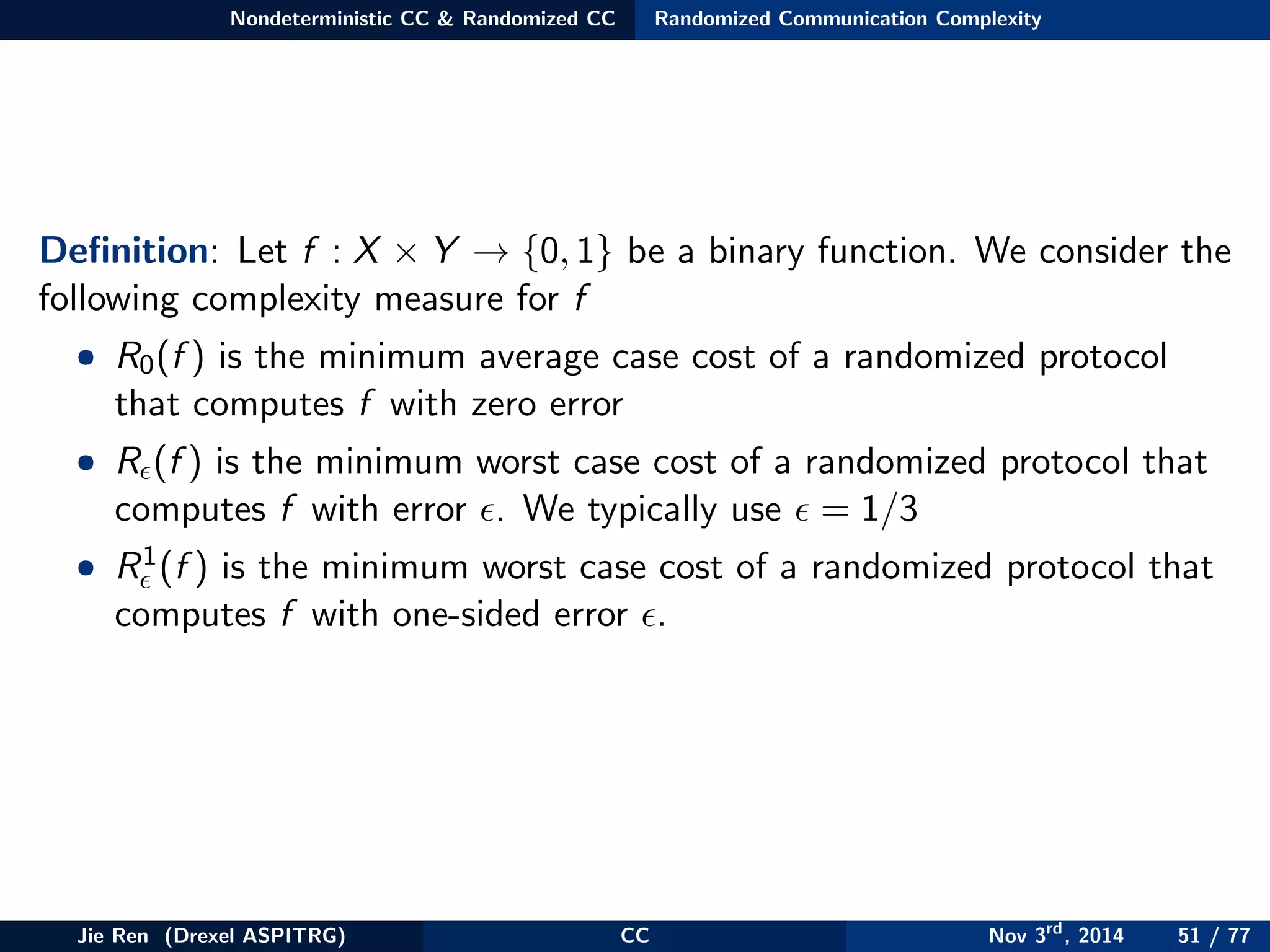

Definition: Let P be a randomized protocol. All the probabilities below

are over random choices of rA and rB.

• P computes a function f with zero error

• P computes a function f with −error if for all (x, y)

P[P(x, y) = f (x, y)] ≥ 1 − (26)

• P computes a function f with one-sided −error if for all (x, y) such

that f (x, y) = 0

P[P(x, y) = 0] = 1, (27)

and for all (x, y) such that f (x, y) = 1,

P[P(x, y) = 1] ≥ 1 − (28)

Jie Ren (Drexel ASPITRG) CC Nov 3rd

, 2014 50 / 77](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/00d94d57-e034-40a9-820b-9e25fe7ae580-150309221050-conversion-gate01/75/CommunicationComplexity1_jieren-50-2048.jpg)

![Nondeterministic CC & Randomized CC Randomized Communication Complexity

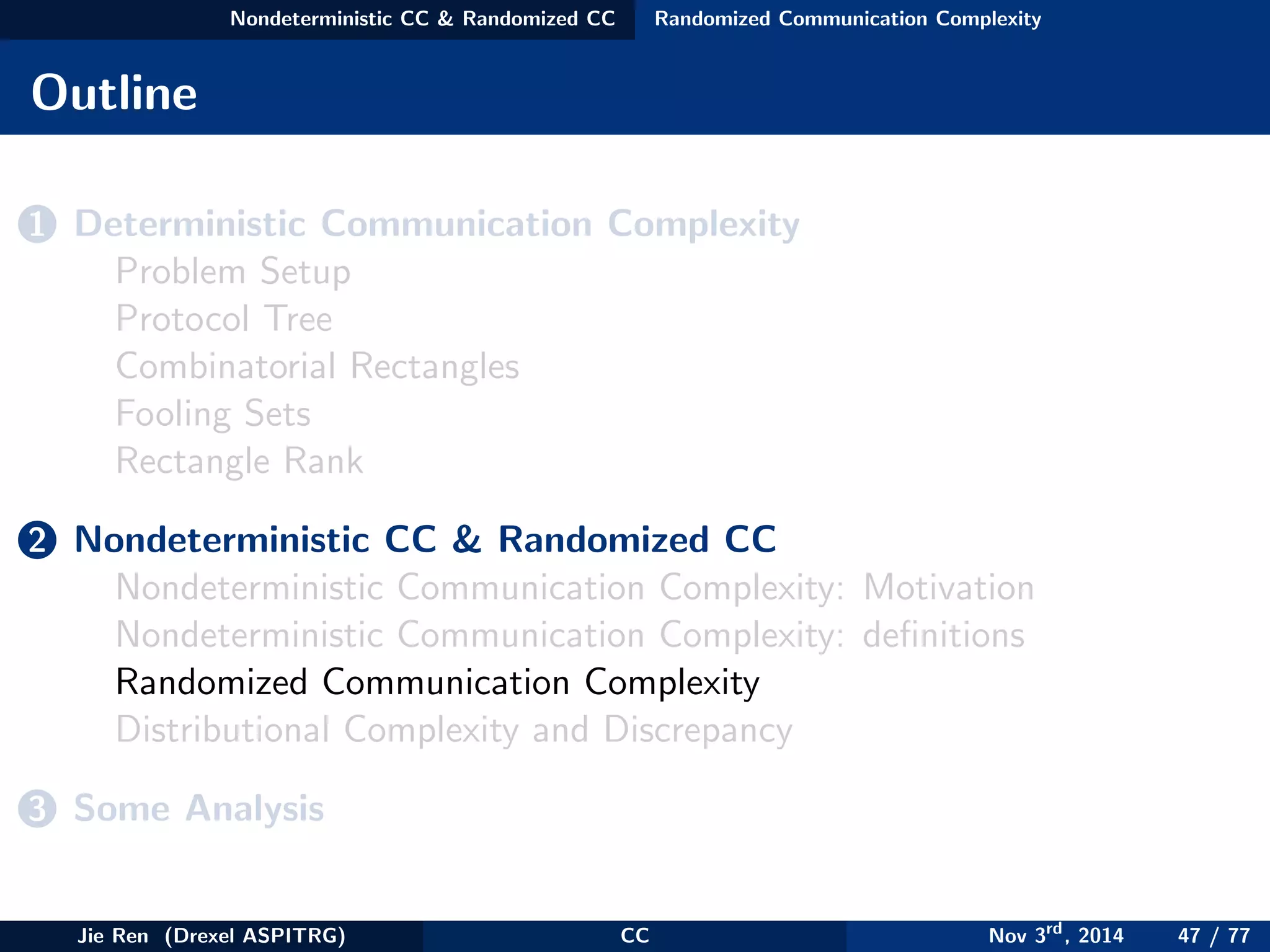

Proposition: Given a protocol P that makes an error /2 and the average

number of bits exchanged is t, it can always be modified as follows:

execute P as long as at most 2t/ bits are exchanged, if the protocol

finishes, use its output, otherwise output 0. This gives a worst case cost

2t/ with error upper bounded by .

Proof:

t =

ra,rb,x,y

cc · p(ra, rb, x, y)

=

cc≤2t/

cc · p(ra, rb, x, y) +

cc>2t/

cc · p(ra, rb, x, y)

≥

cc>2t/

cc · p(ra, rb, x, y) ≥

2t

Pr[cc > 2t/ ]

(29)

Hence,

Pr[err] ≤

2

Pr[P ends] + 1 · Pr[P not ends]

≤

2

+

t

2t/

=

(30)

Jie Ren (Drexel ASPITRG) CC Nov 3rd

, 2014 53 / 77](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/00d94d57-e034-40a9-820b-9e25fe7ae580-150309221050-conversion-gate01/75/CommunicationComplexity1_jieren-53-2048.jpg)

![Nondeterministic CC & Randomized CC Randomized Communication Complexity

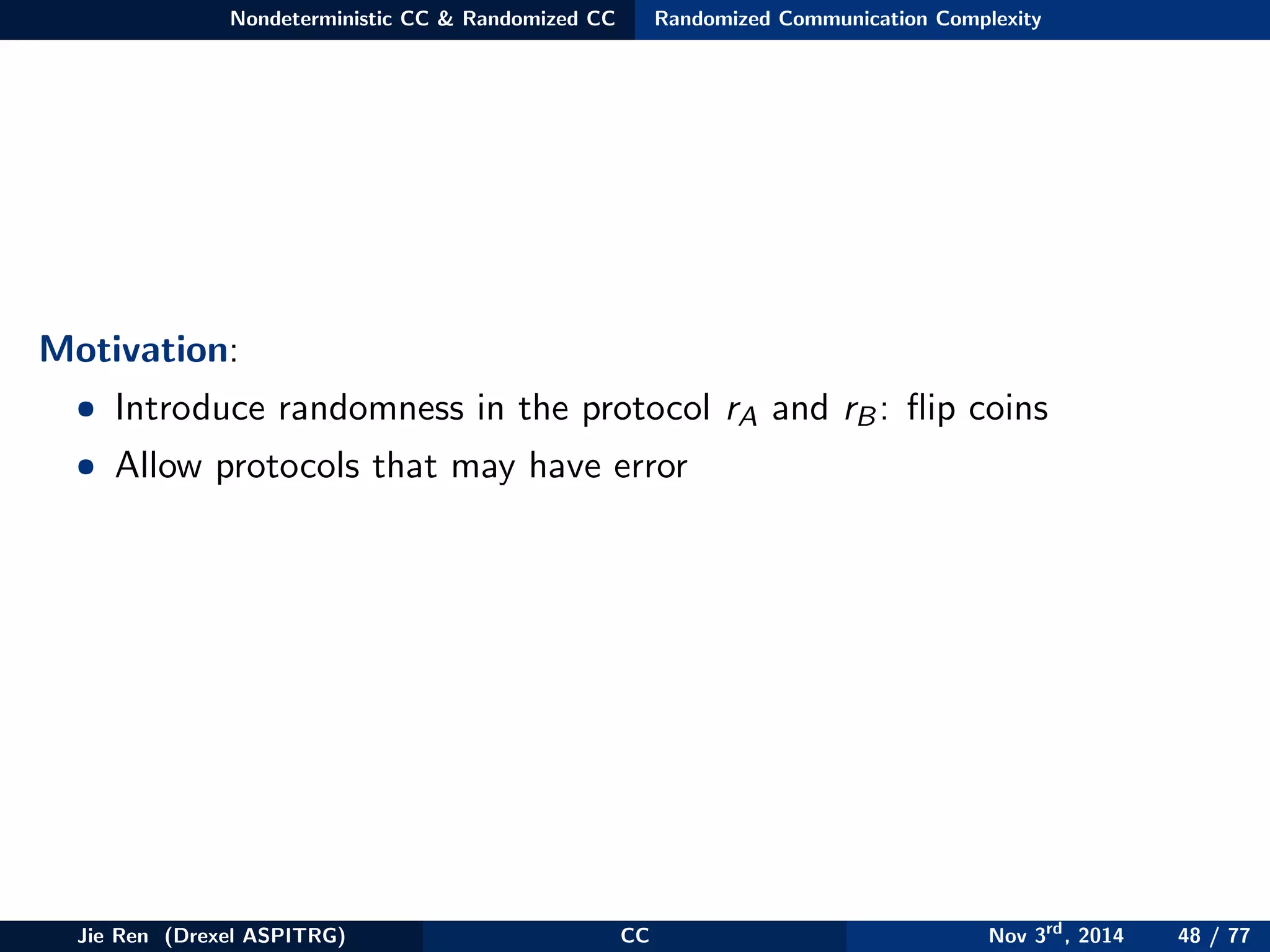

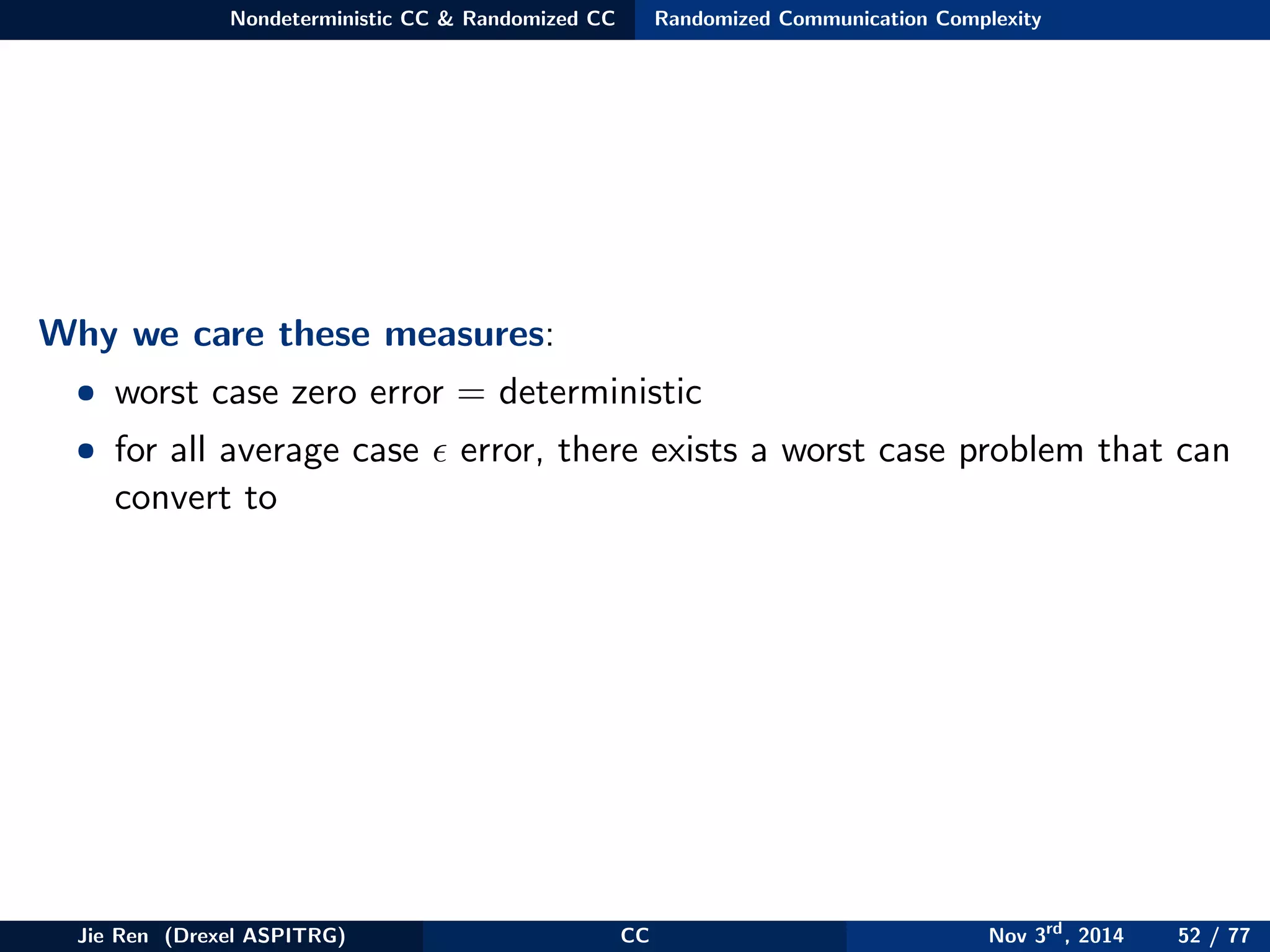

1 For all 0 < ≤ < 1/2,

R (f ) ≤ O(log · R (f )) (31)

2 For all 0 < ≤ 1/2,

R (f ) ≤ R1

(f ) ≤ O(log −1

R0(f )) (32)

3 For all 0 < ≤ 1/2,

R0(f ) = Θ(max[R1

(f ), R1

(not(f ))]) (33)

Jie Ren (Drexel ASPITRG) CC Nov 3rd

, 2014 54 / 77](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/00d94d57-e034-40a9-820b-9e25fe7ae580-150309221050-conversion-gate01/75/CommunicationComplexity1_jieren-54-2048.jpg)

![Nondeterministic CC & Randomized CC Randomized Communication Complexity

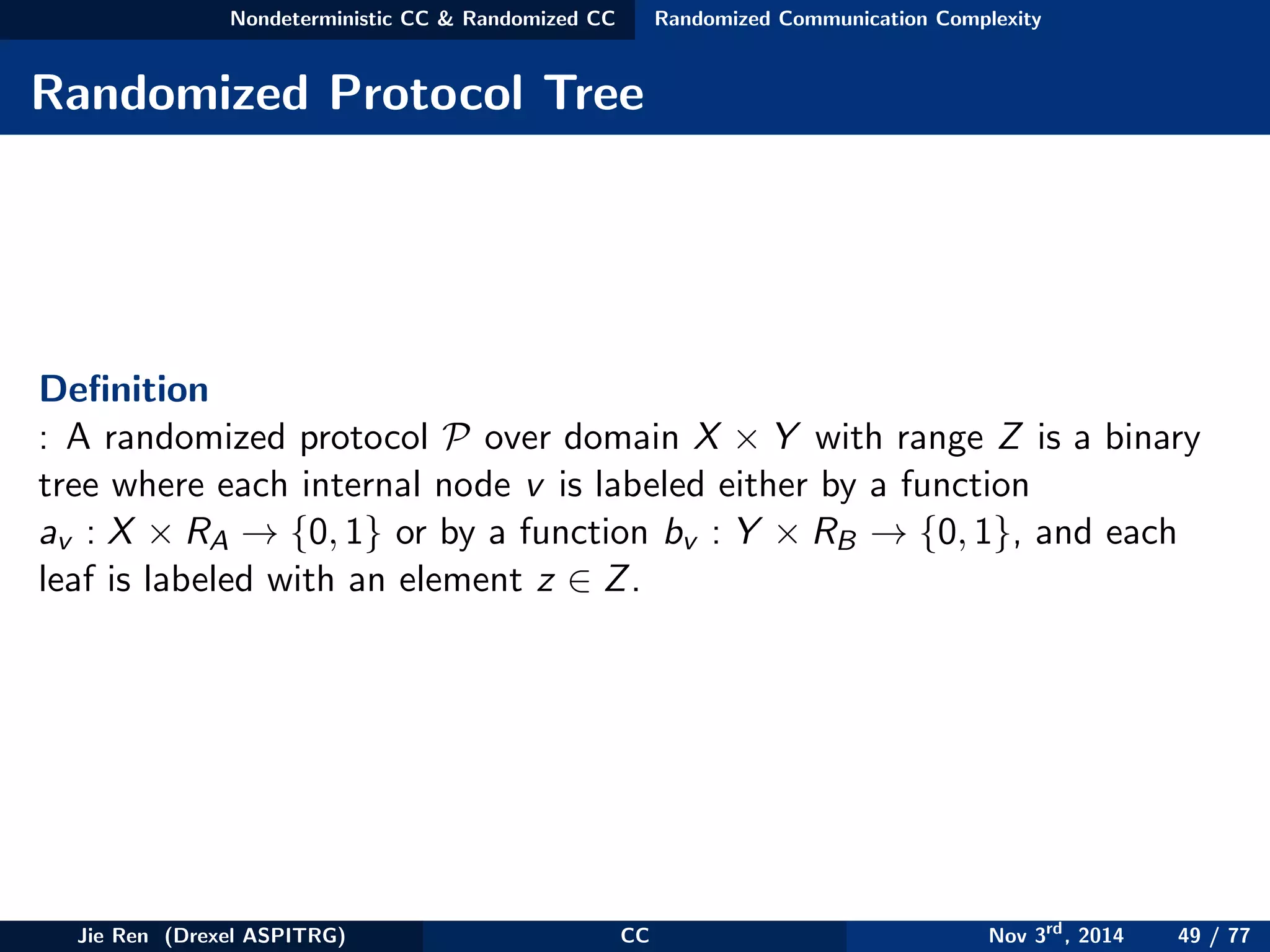

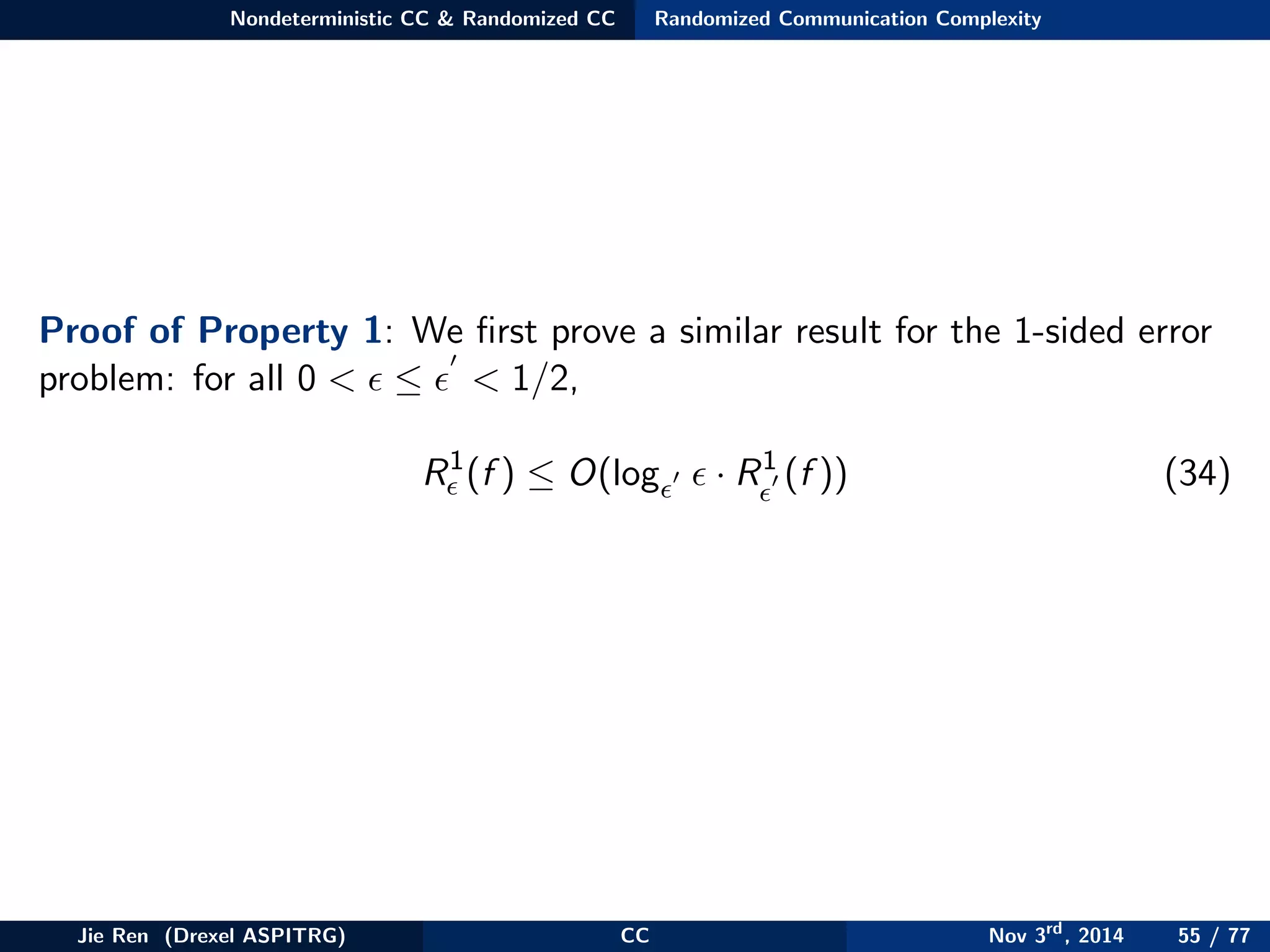

Proof of Property 1: Given a randomized protocol P with worst case

cost T bits and one-sided error no greater than < 1/2, we can build a

new protocol P with worst case cost nT bits by simply running P n

times. In the new protocol, Alice and Bob will claim f (x, y) = 1 if and

only if there exists at least one time among the n repeating protocols that

they will output 1. Now we bound the error for the new protocol P :

P[err|f (x, y) = 0] = 0 (35)

P[err|f (x, y) = 1] = P[all n trails output 0|f (x, y) = 1]

= ( )n

(36)

Therefore, if we repeat P log times, we can guarantee to reduce the

one-sided error to .

Jie Ren (Drexel ASPITRG) CC Nov 3rd

, 2014 56 / 77](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/00d94d57-e034-40a9-820b-9e25fe7ae580-150309221050-conversion-gate01/75/CommunicationComplexity1_jieren-56-2048.jpg)

![Nondeterministic CC & Randomized CC Randomized Communication Complexity

Proof of Property 1: Now we prove property 1. We still run P n times,

each gives an output Xi , i ∈ {1, . . . , n}. In the new protocol, Alice and

Bob will claim f (x, y) = 1 if and only if

1

n

i

Xi >

1

2

(37)

Now we bound the error for the new protocol P :

P[err|f (x, y) = 0] ≤

n

i= n/2

n

i

( )i

(1 − )n−i

≤ ( )n

(38)

P[err|f (x, y) = 1] ≤

n

i= n/2

n

i

( )i

(1 − )n−i

≤ ( )n

(39)

Therefore, if we repeat P log times, we can also guarantee to reduce

the two-sided error to .

Jie Ren (Drexel ASPITRG) CC Nov 3rd

, 2014 57 / 77](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/00d94d57-e034-40a9-820b-9e25fe7ae580-150309221050-conversion-gate01/75/CommunicationComplexity1_jieren-57-2048.jpg)

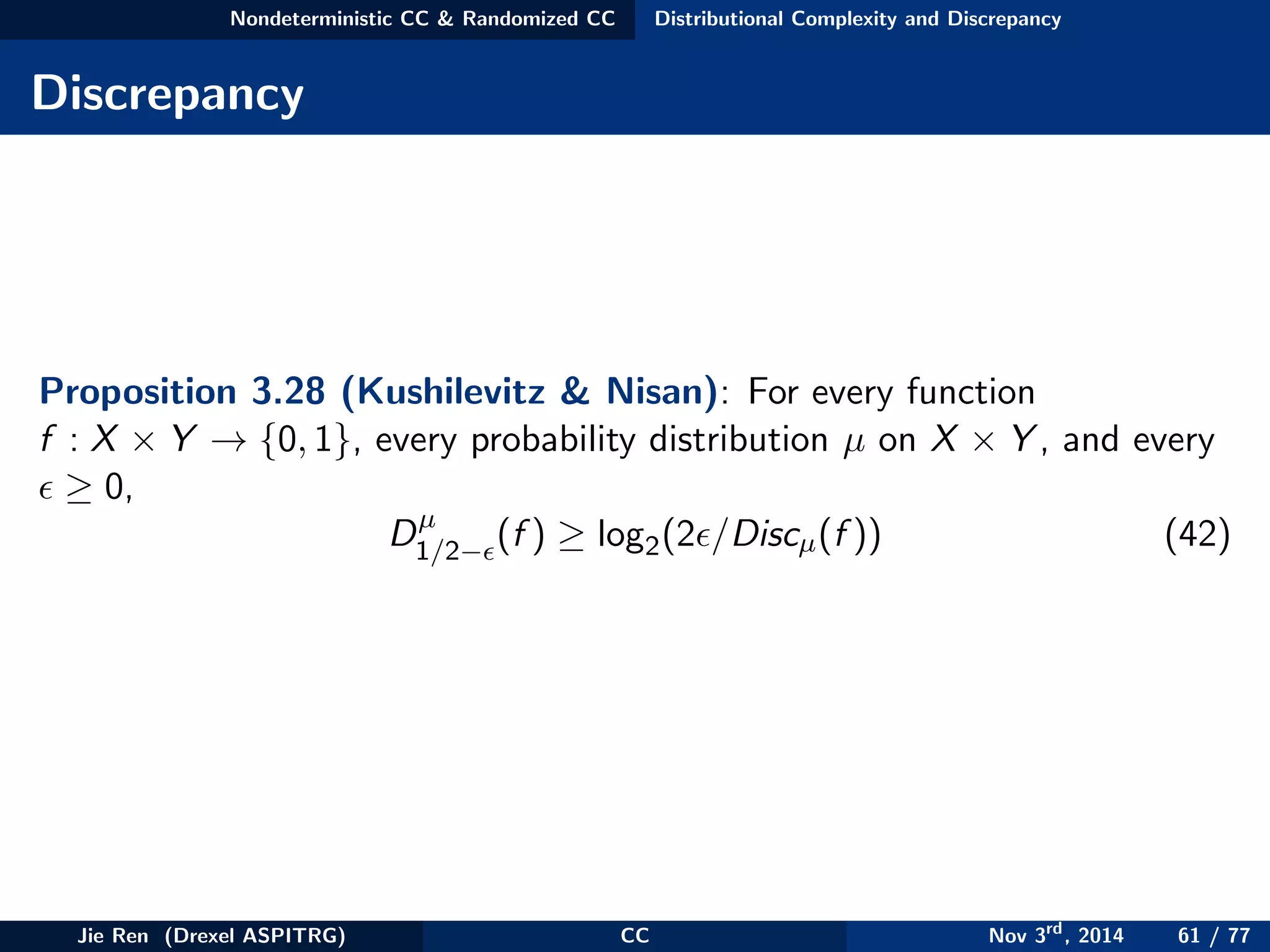

![Nondeterministic CC & Randomized CC Distributional Complexity and Discrepancy

Discrepancy

Motivation: Allow those rectangles that partition the support to be

“almost” f -monochromatic.

Definition: Let f : X × Y → {0, 1} be a function, R be any rectangle,

and µ be a probability distribution on X × Y , Denote

Discµ(R, f ) = |P

µ

[f (x, y) = 0 & (x, y) ∈ R] − P

µ

[f (x, y) = 1 & (x, y) ∈ R]|

(40)

The discrepancy of f according to µ is,

Discµ(f ) = max

R

Discµ(R, f ) (41)

Jie Ren (Drexel ASPITRG) CC Nov 3rd

, 2014 60 / 77](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/00d94d57-e034-40a9-820b-9e25fe7ae580-150309221050-conversion-gate01/75/CommunicationComplexity1_jieren-60-2048.jpg)

![Nondeterministic CC & Randomized CC Distributional Complexity and Discrepancy

Discrepancy

Proof: Given any P with c bits to compute f , we have

2 ≤ P[P(x, y) = f (x, y)] − P[P(x, y) = f (x, y)]

= (P[P(x, y) = f (x, y)&(x, y) ∈ R ]

−P[P(x, y) = f (x, y)&(x, y) ∈ R ])

≤ |P

µ

[f (x, y) = 0 & (x, y) ∈ R ] − P

µ

[f (x, y) = 1 & (x, y) ∈ R ]|

≤ 2c

· Discµ(f )

(43)

Jie Ren (Drexel ASPITRG) CC Nov 3rd

, 2014 62 / 77](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/00d94d57-e034-40a9-820b-9e25fe7ae580-150309221050-conversion-gate01/75/CommunicationComplexity1_jieren-62-2048.jpg)