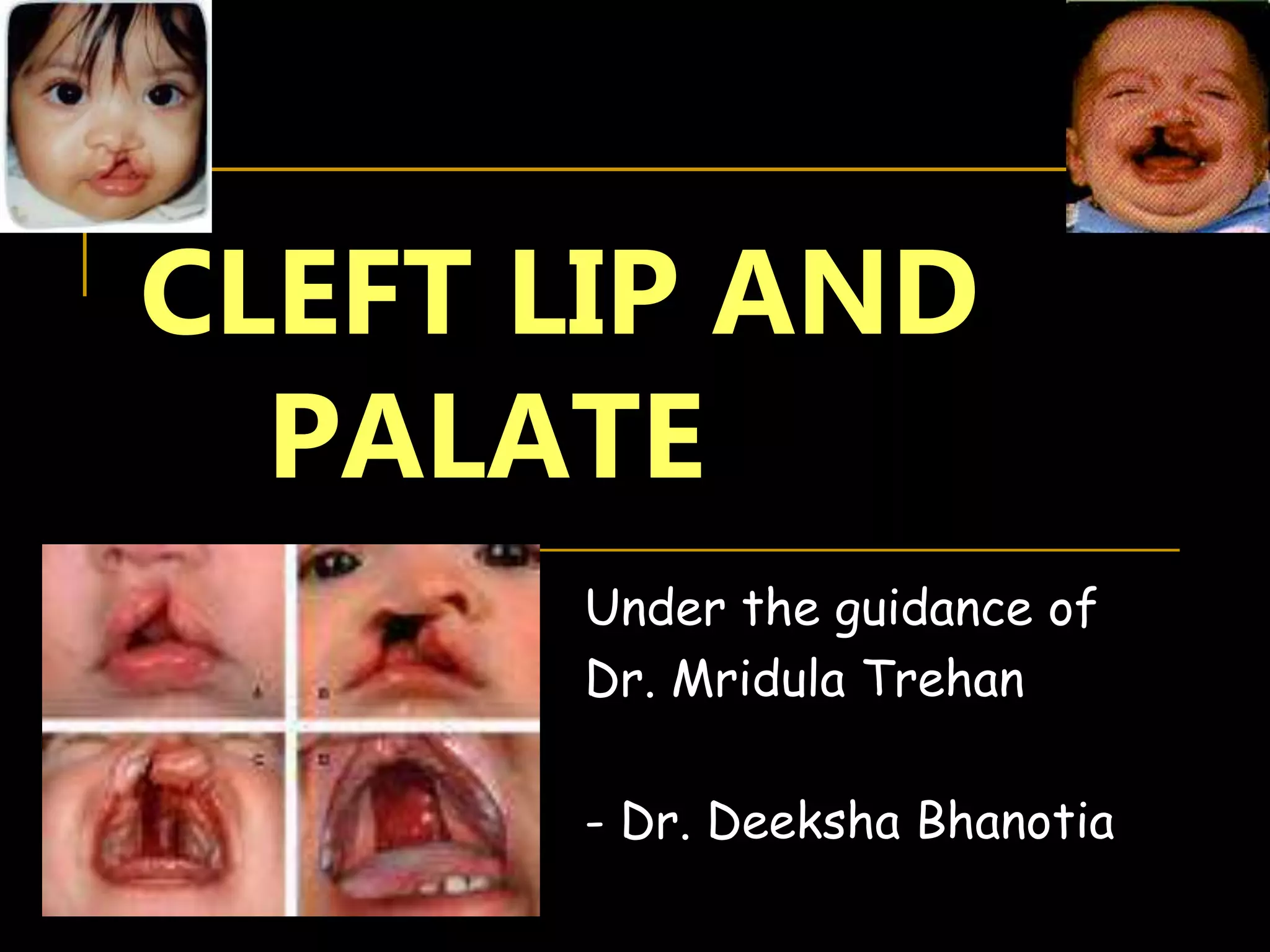

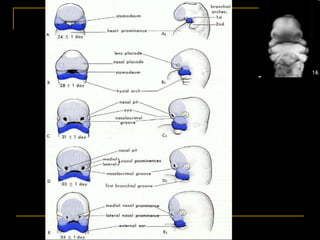

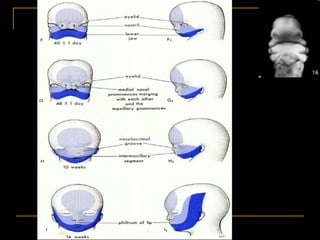

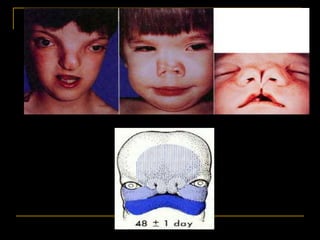

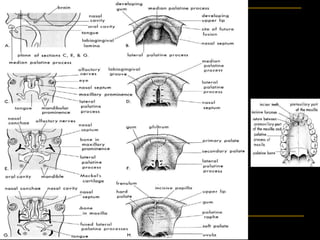

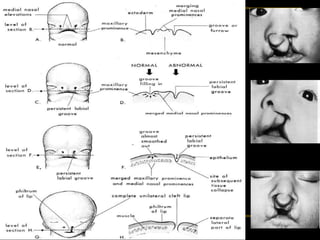

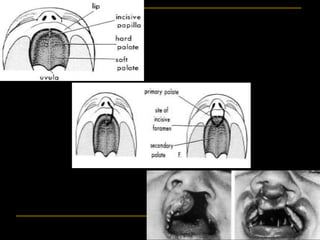

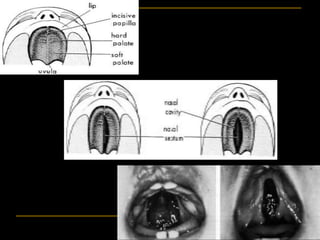

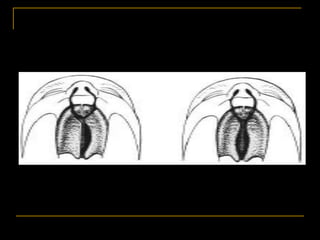

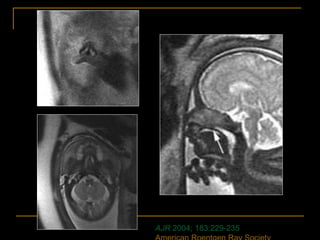

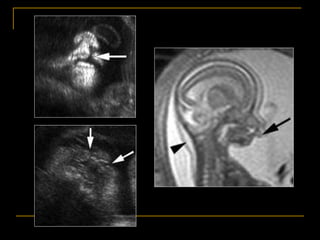

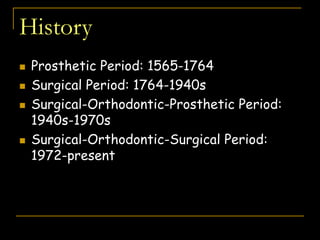

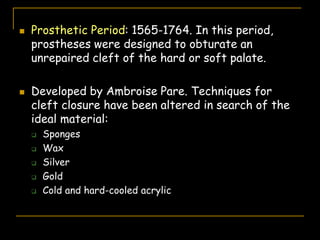

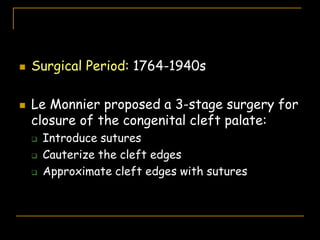

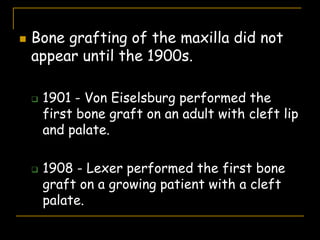

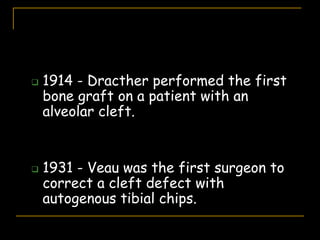

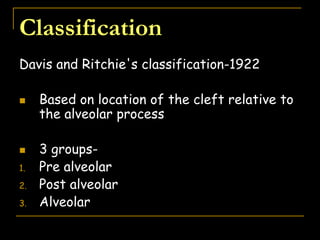

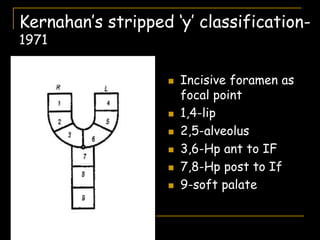

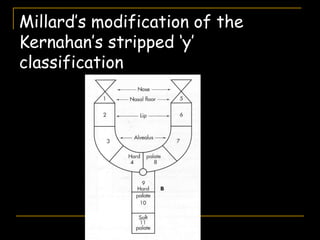

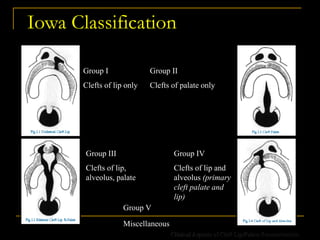

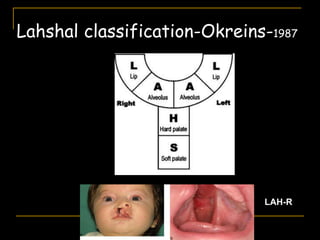

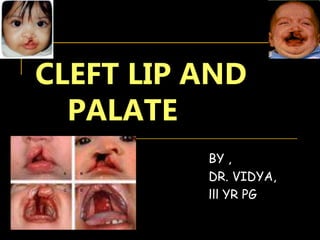

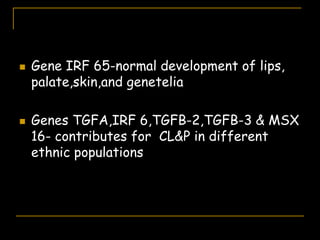

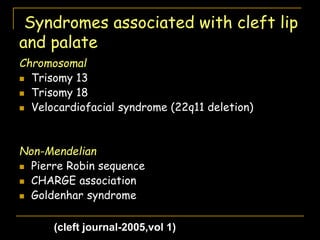

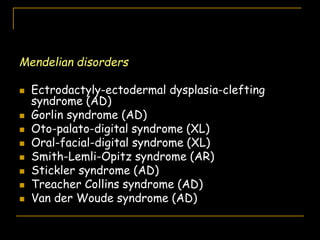

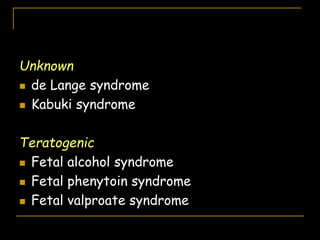

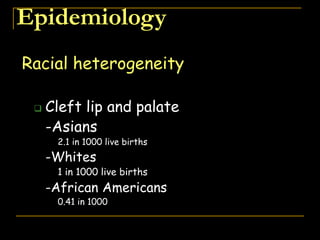

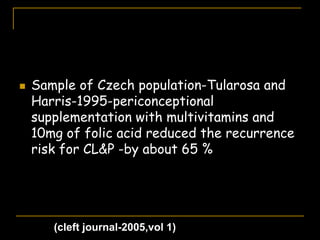

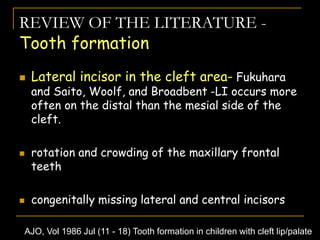

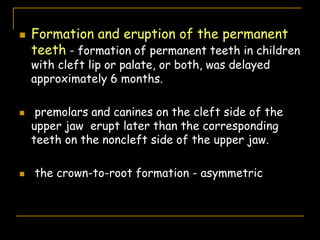

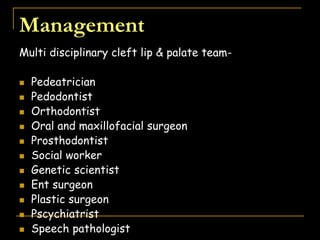

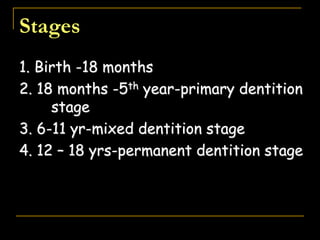

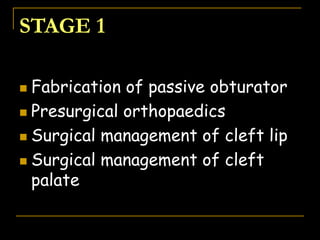

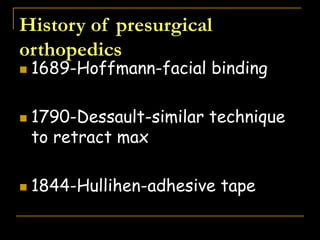

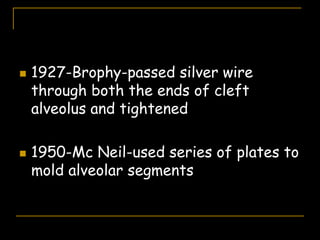

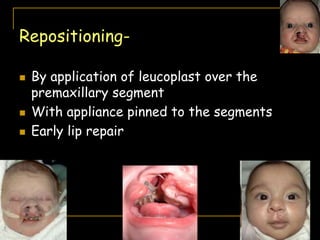

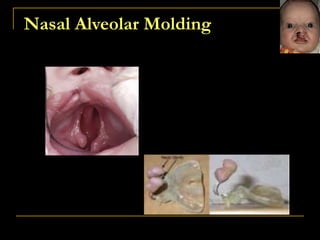

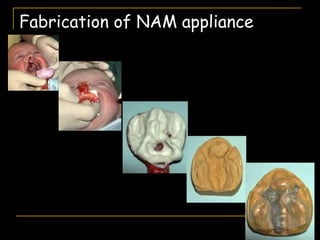

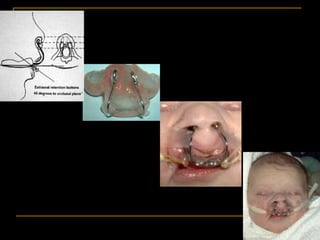

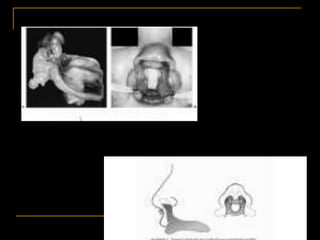

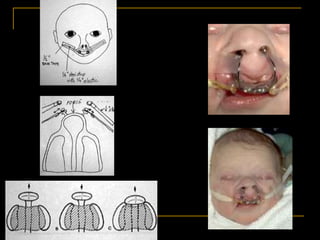

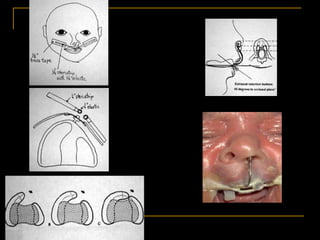

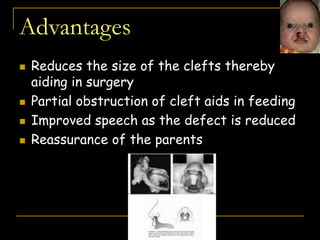

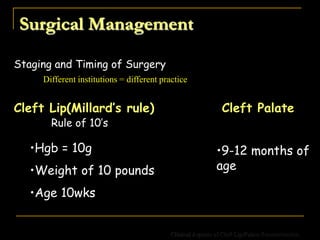

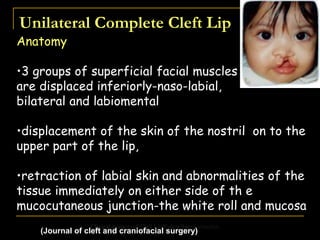

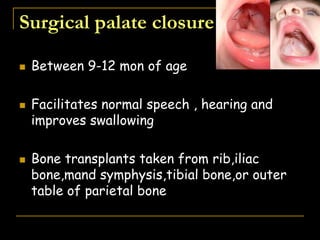

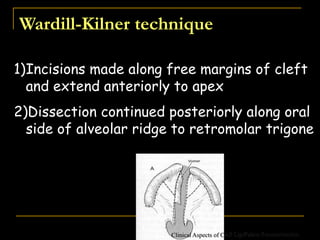

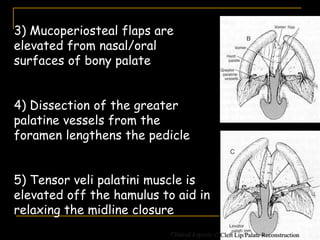

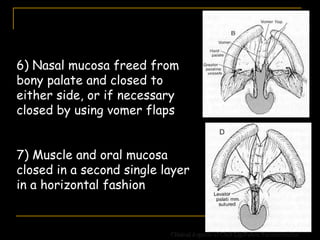

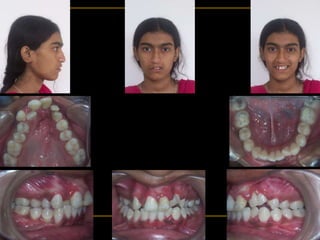

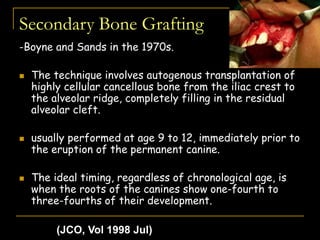

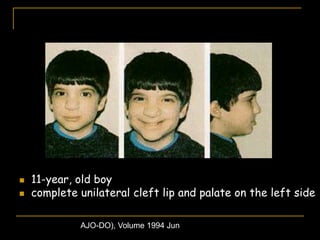

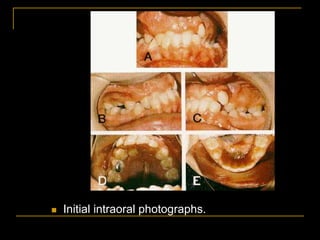

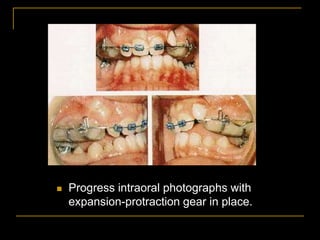

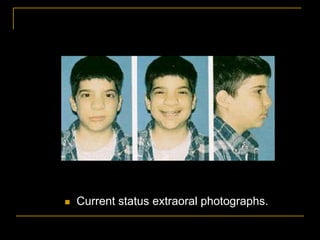

This document discusses cleft lip and palate, including its embryology, historical background, theories of formation, classification systems, etiology, and management. It notes that cleft lip and palate can be caused by hereditary factors, infections, drugs, radiation, or diets during pregnancy. The epidemiology section provides statistics on its prevalence among different racial groups and discusses associated factors like parental age and seasonal variations. Treatment involves a multidisciplinary approach depending on the type and severity of the cleft.