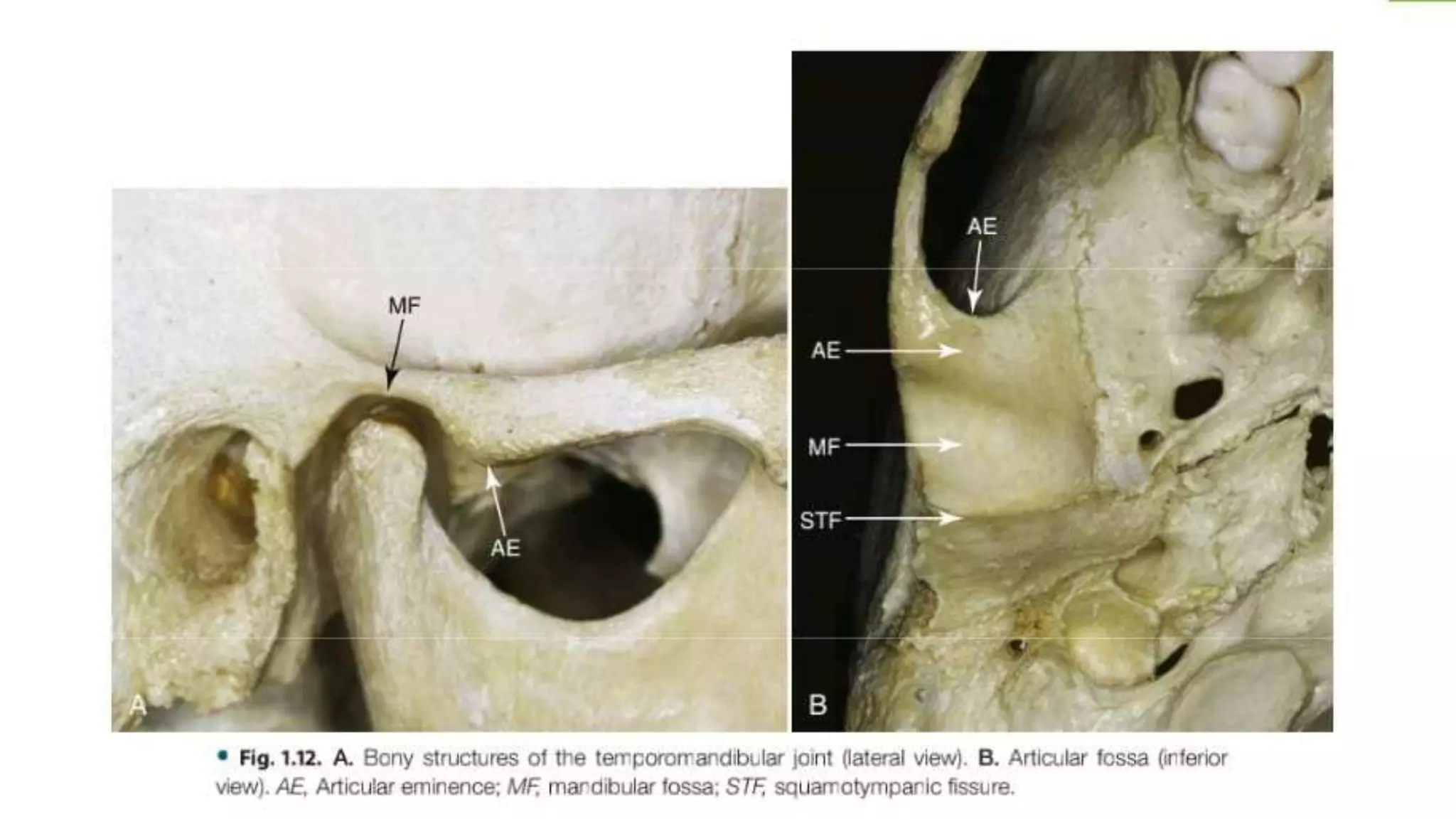

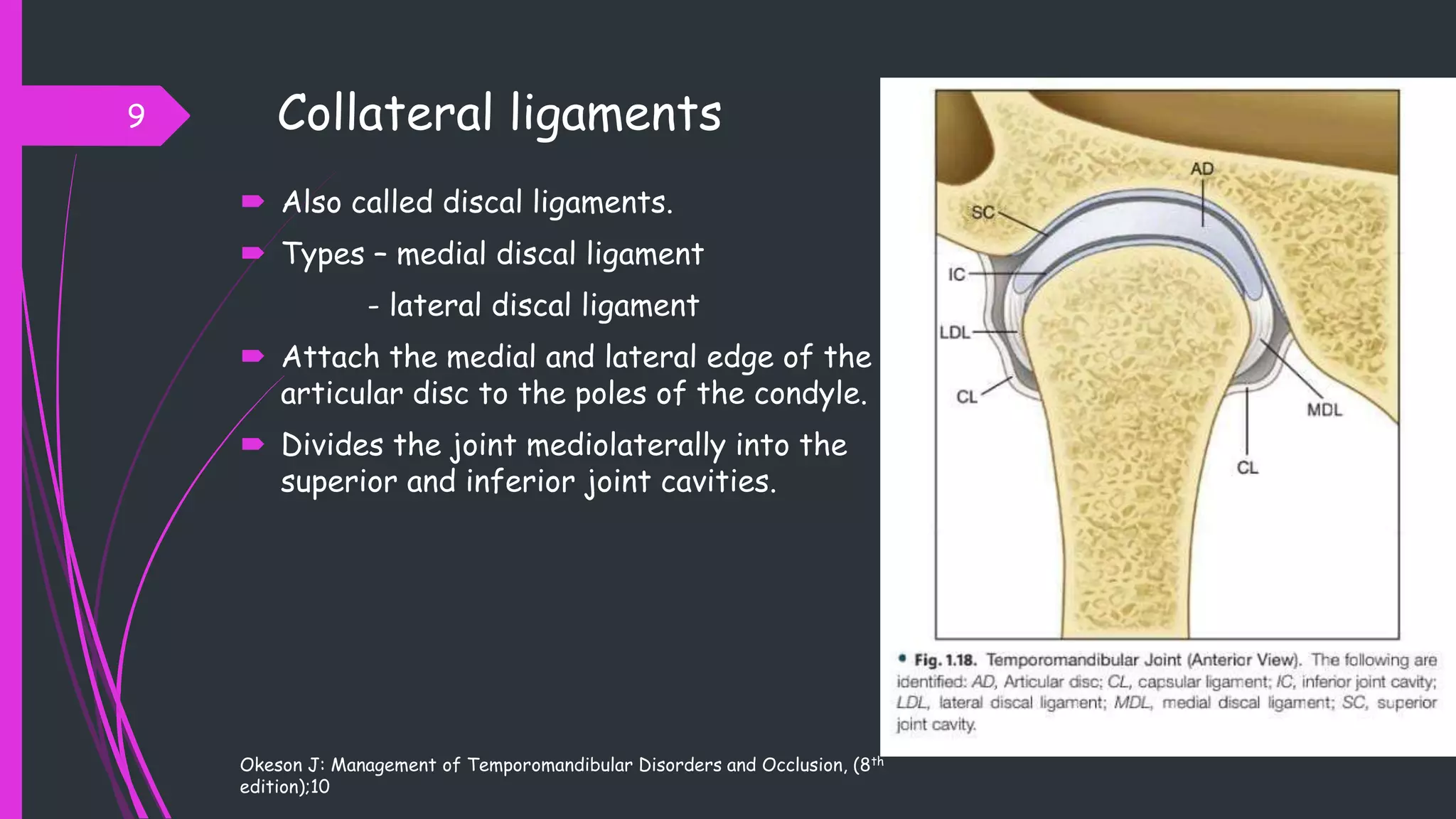

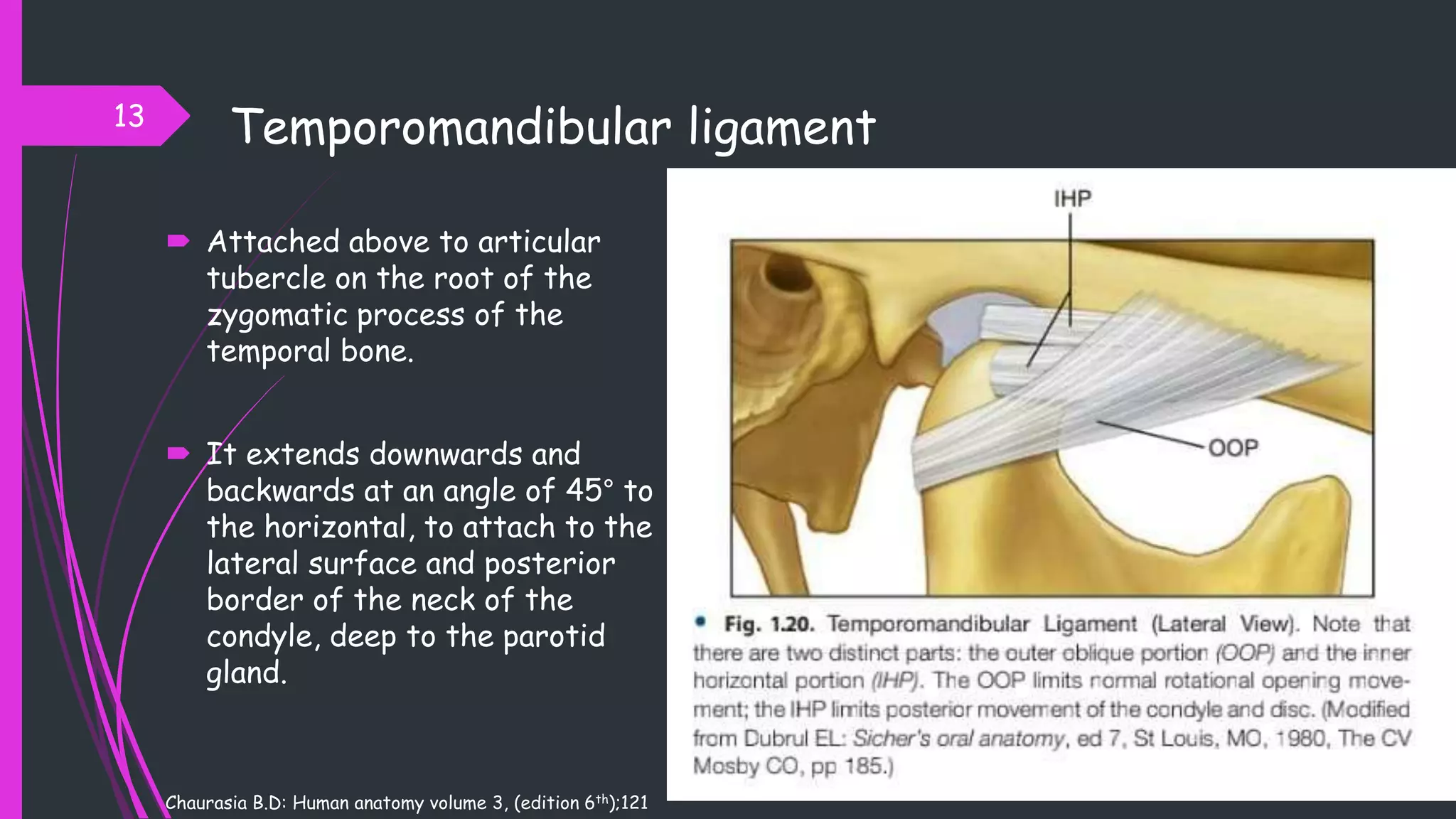

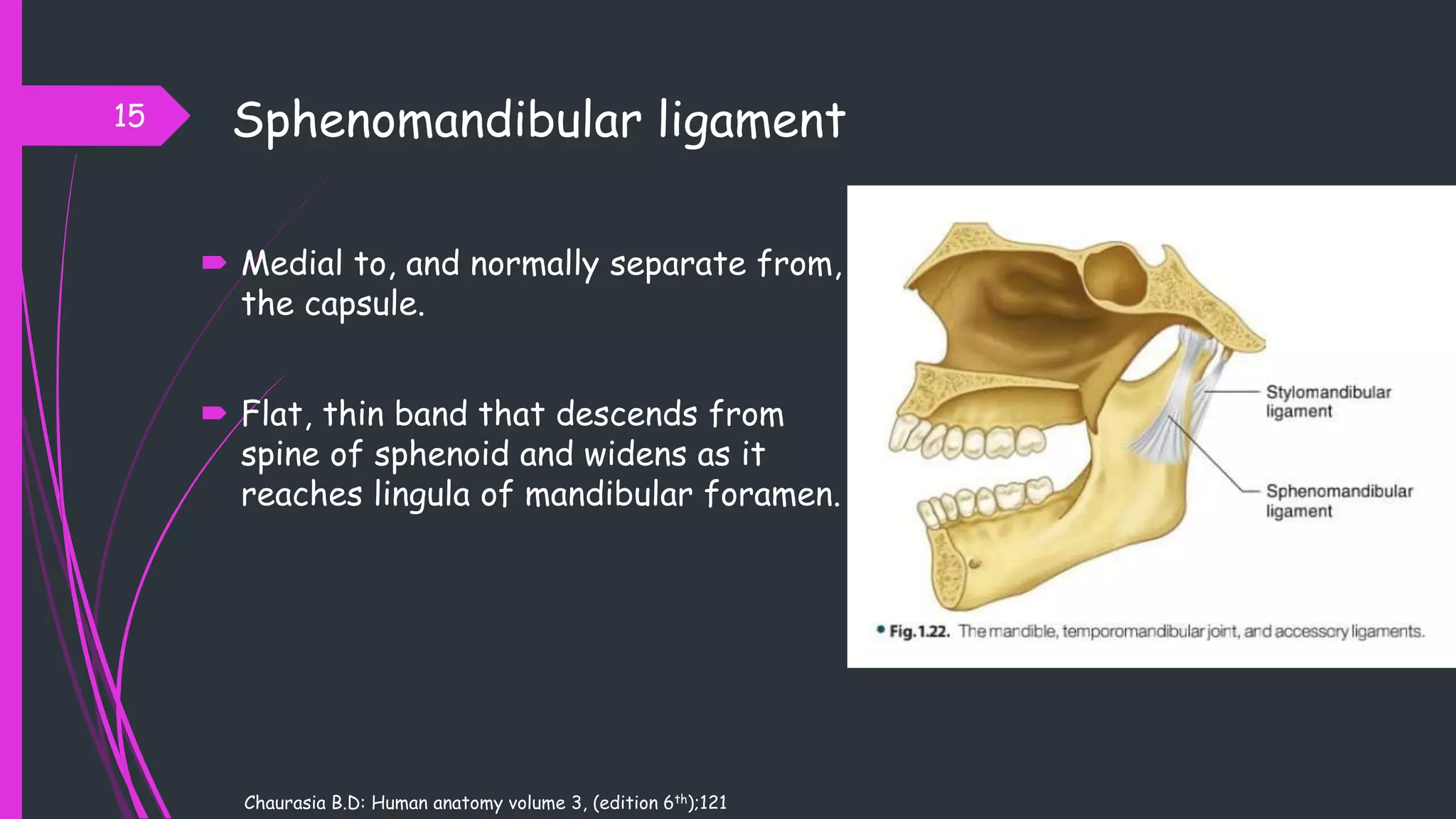

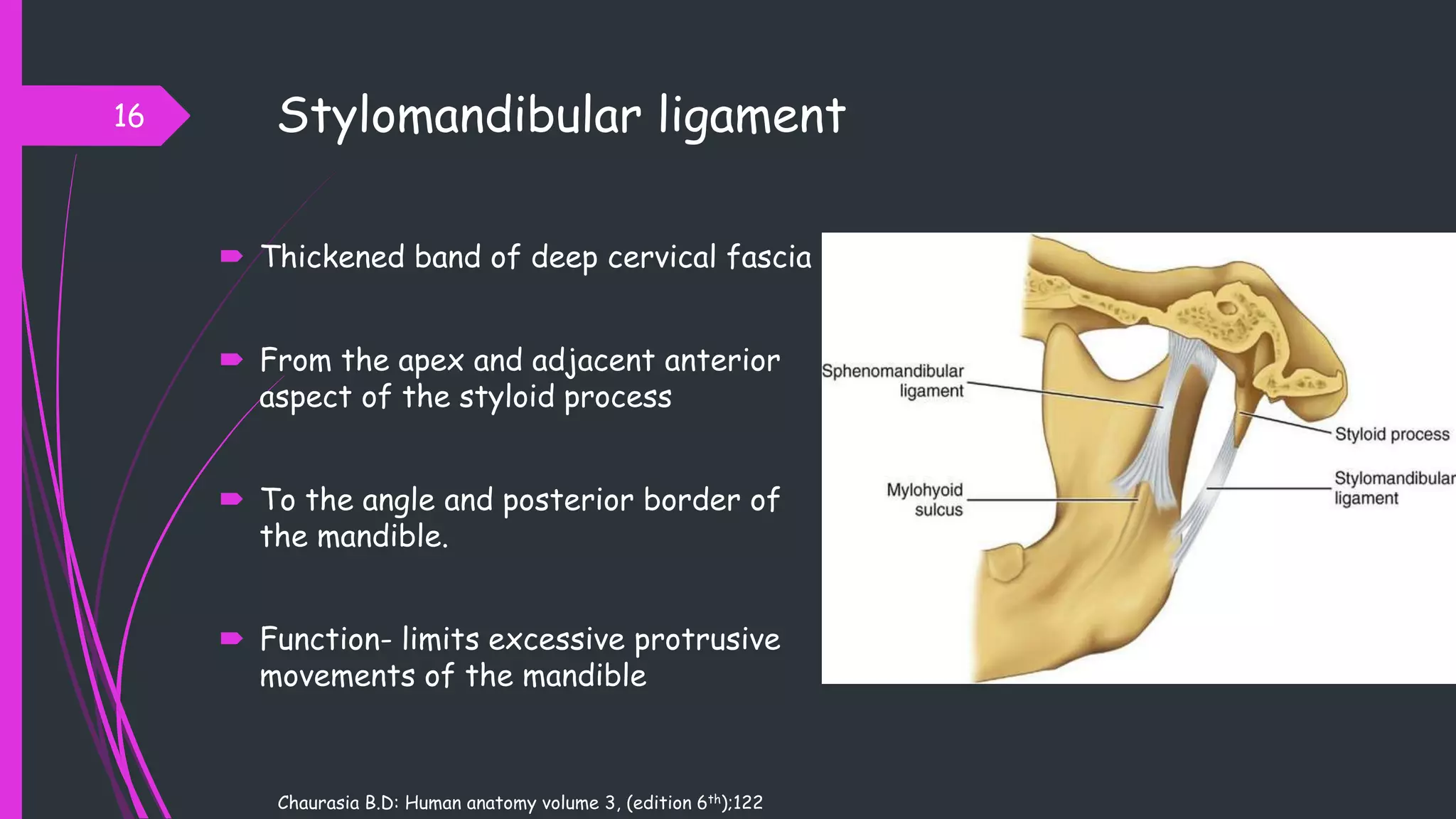

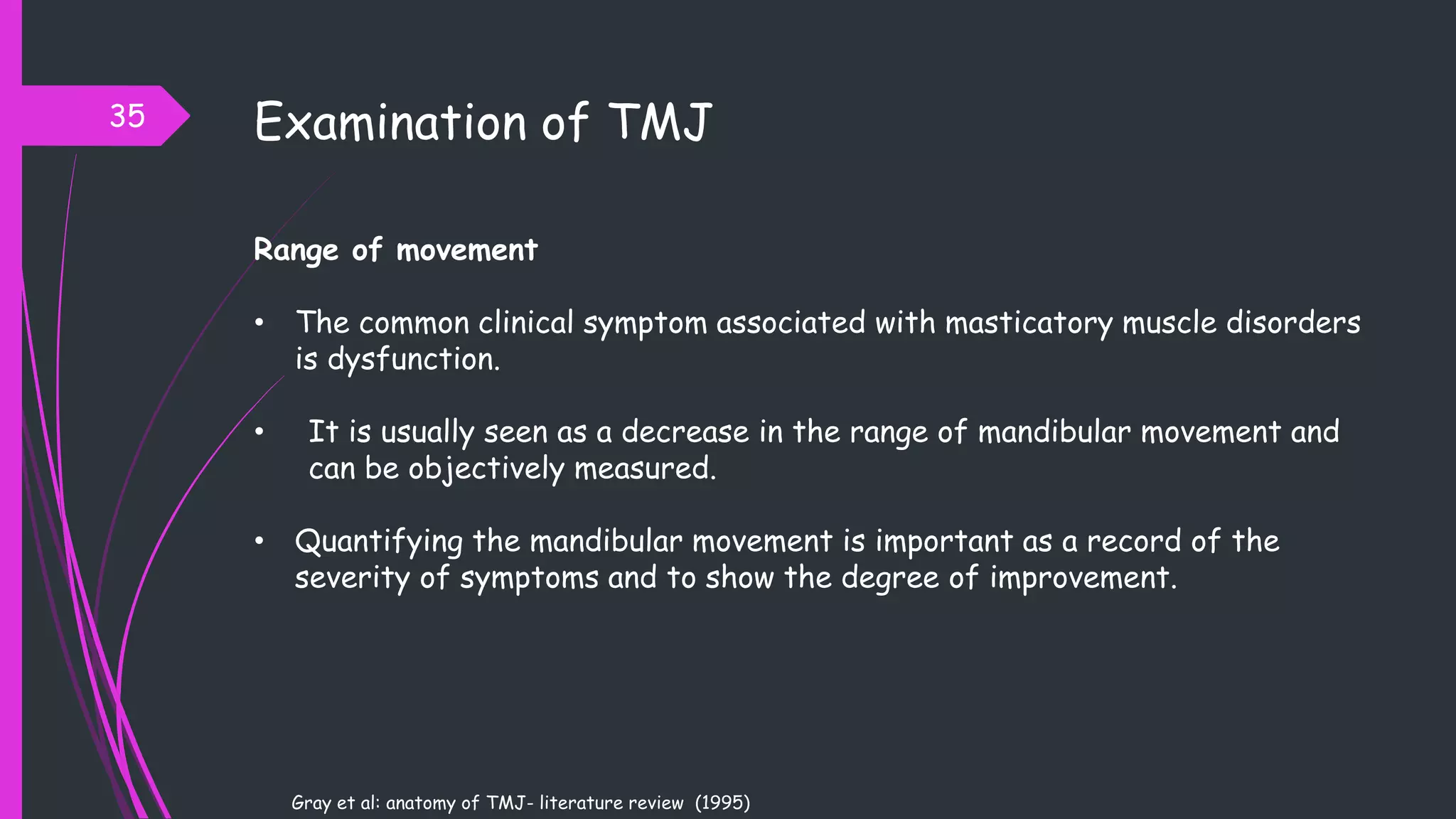

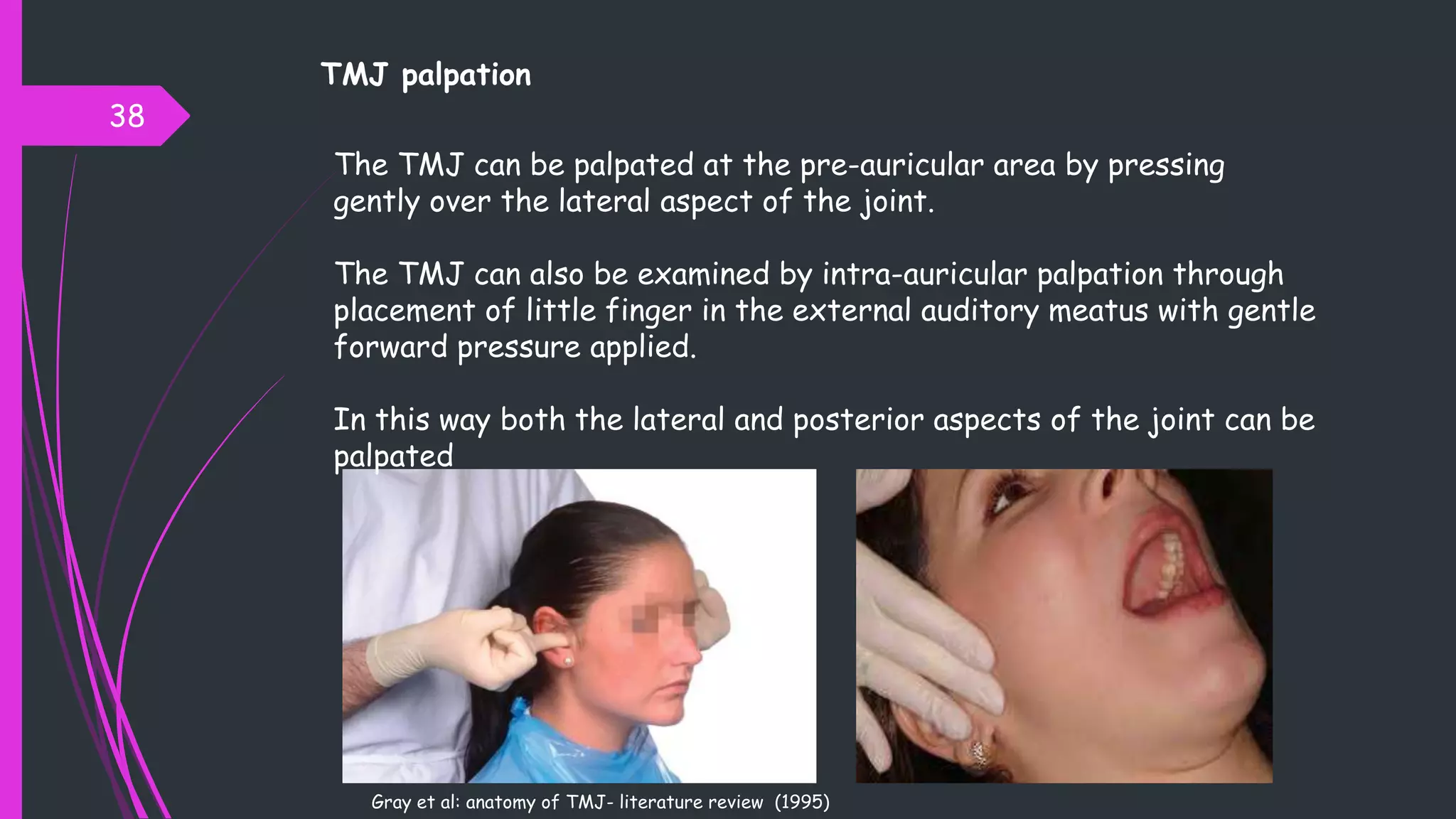

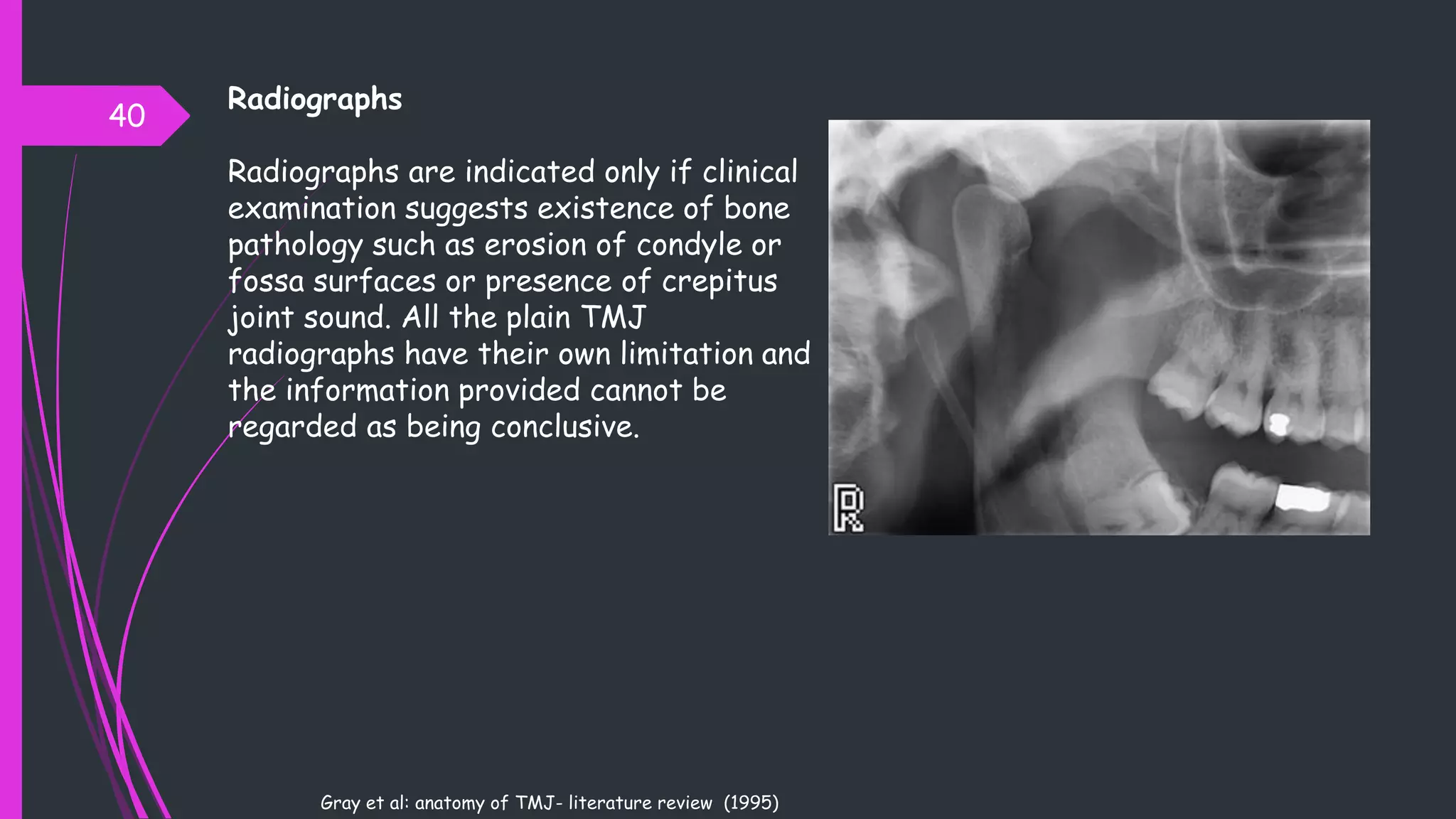

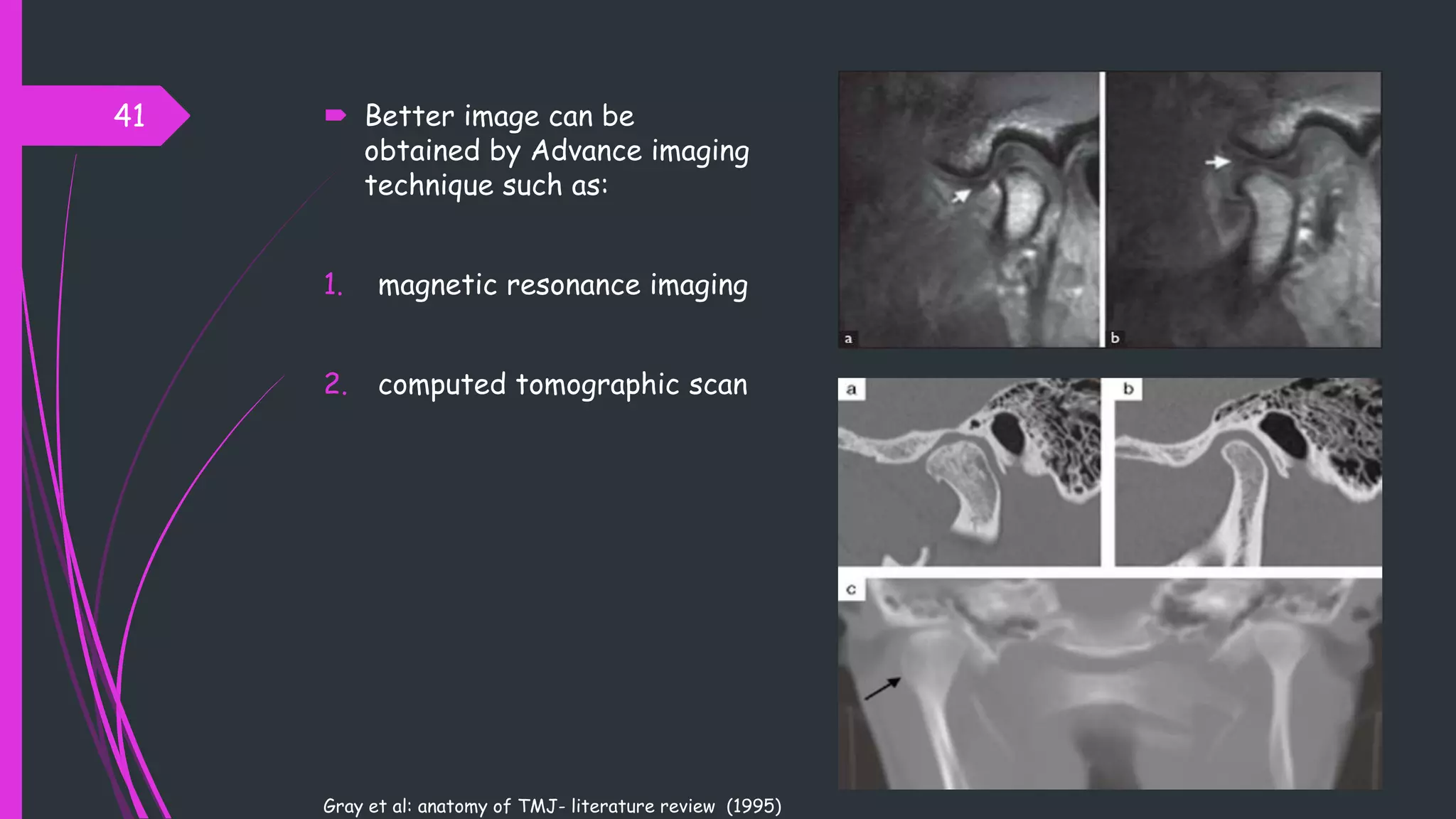

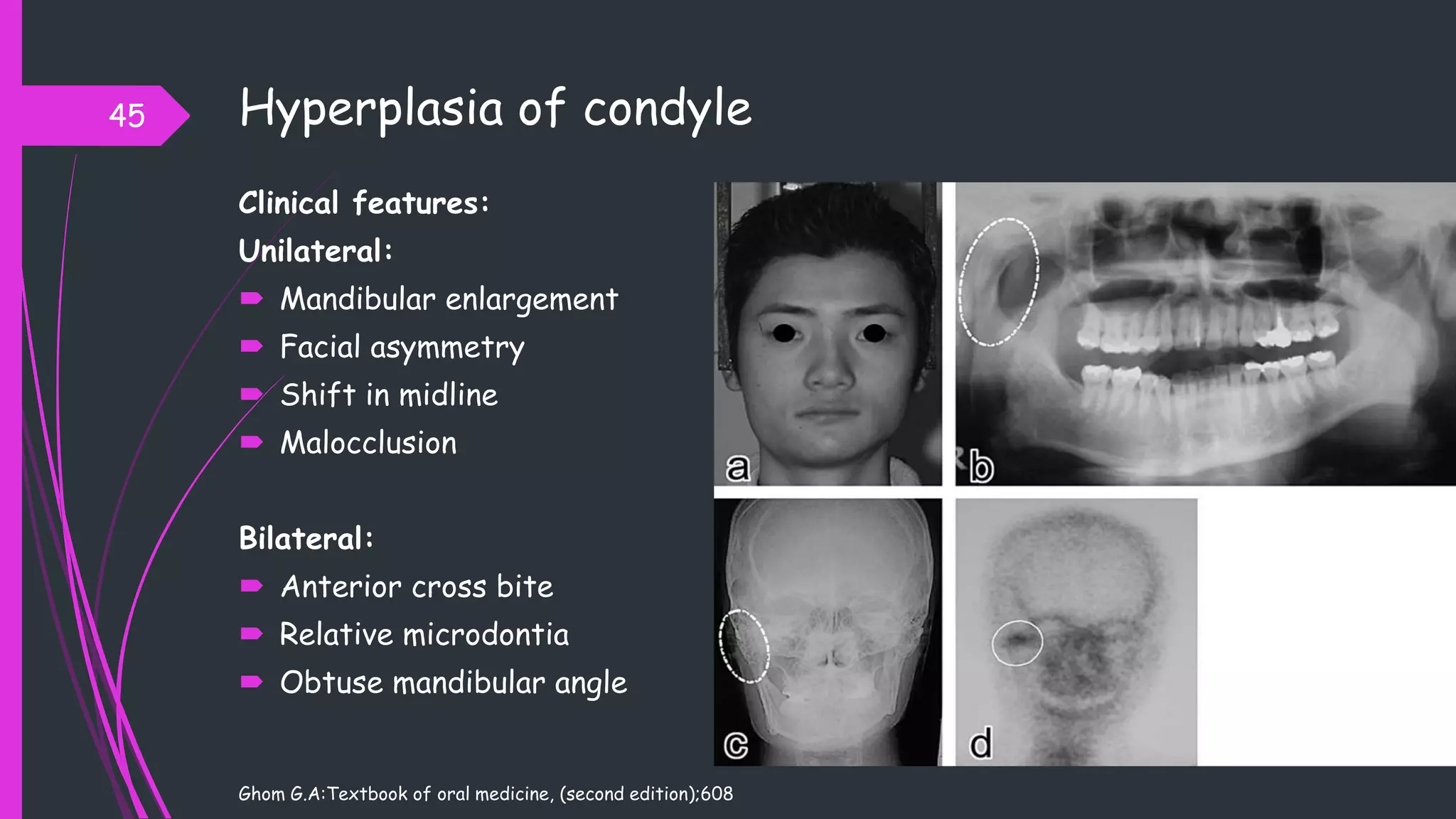

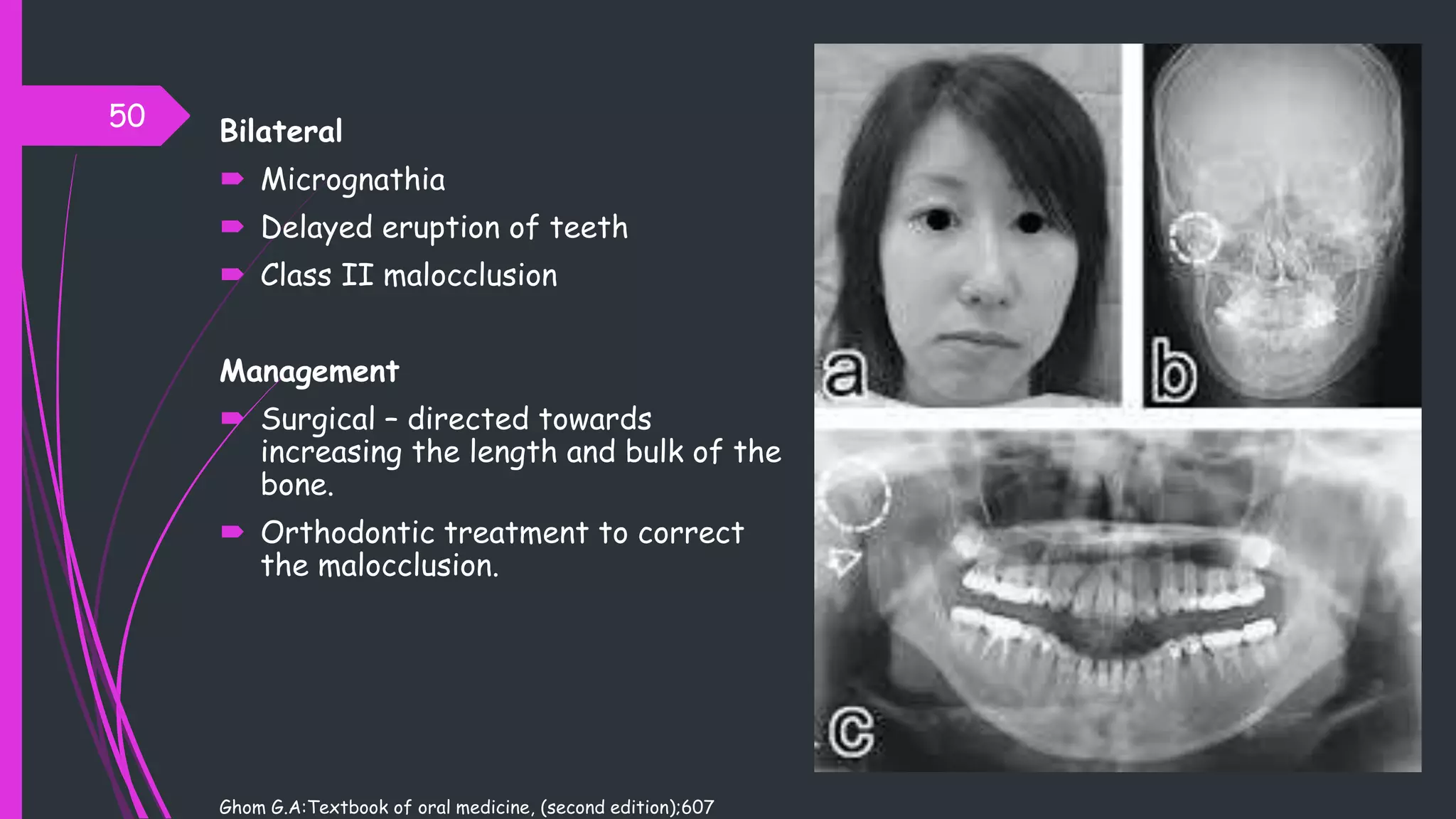

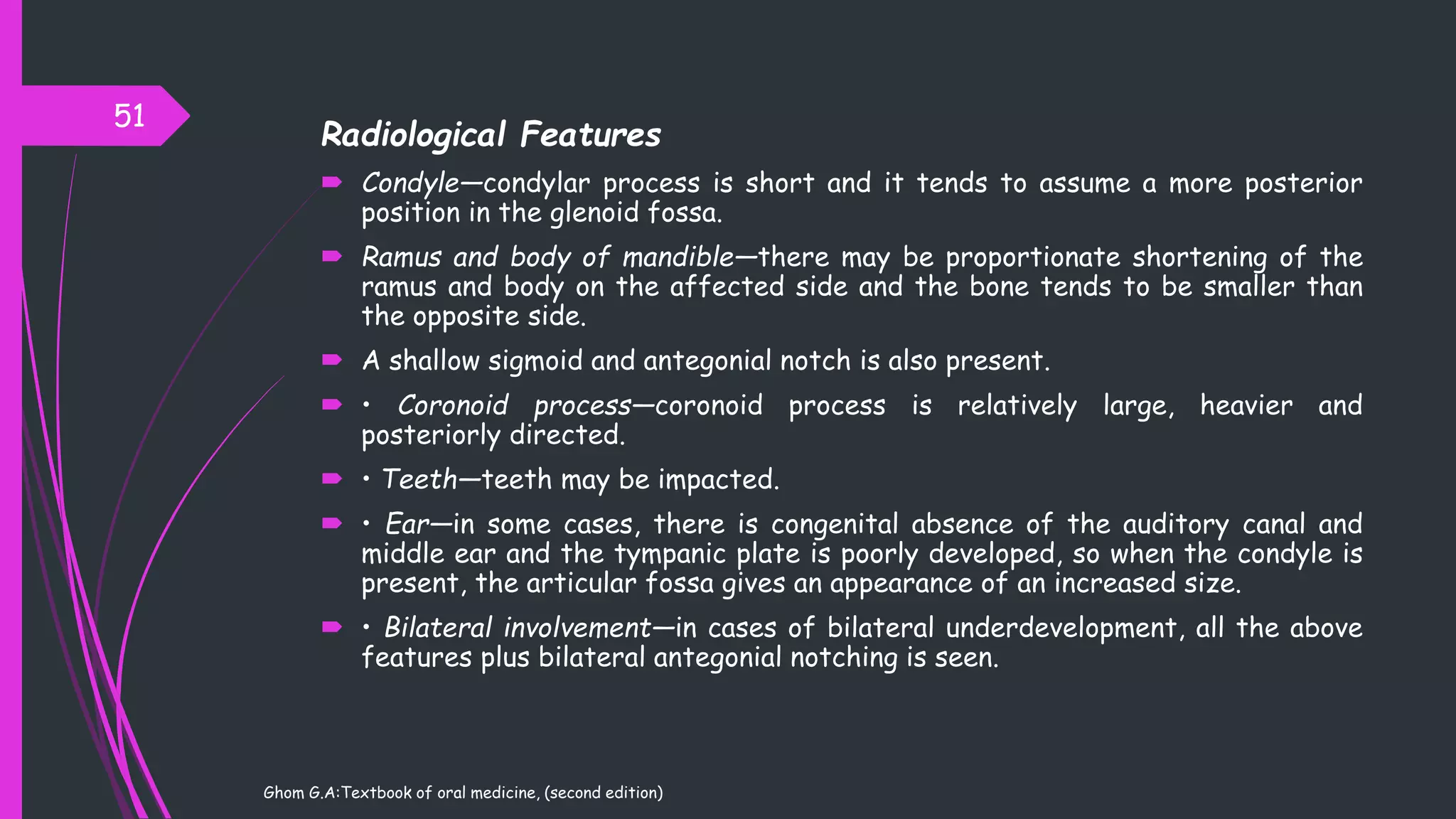

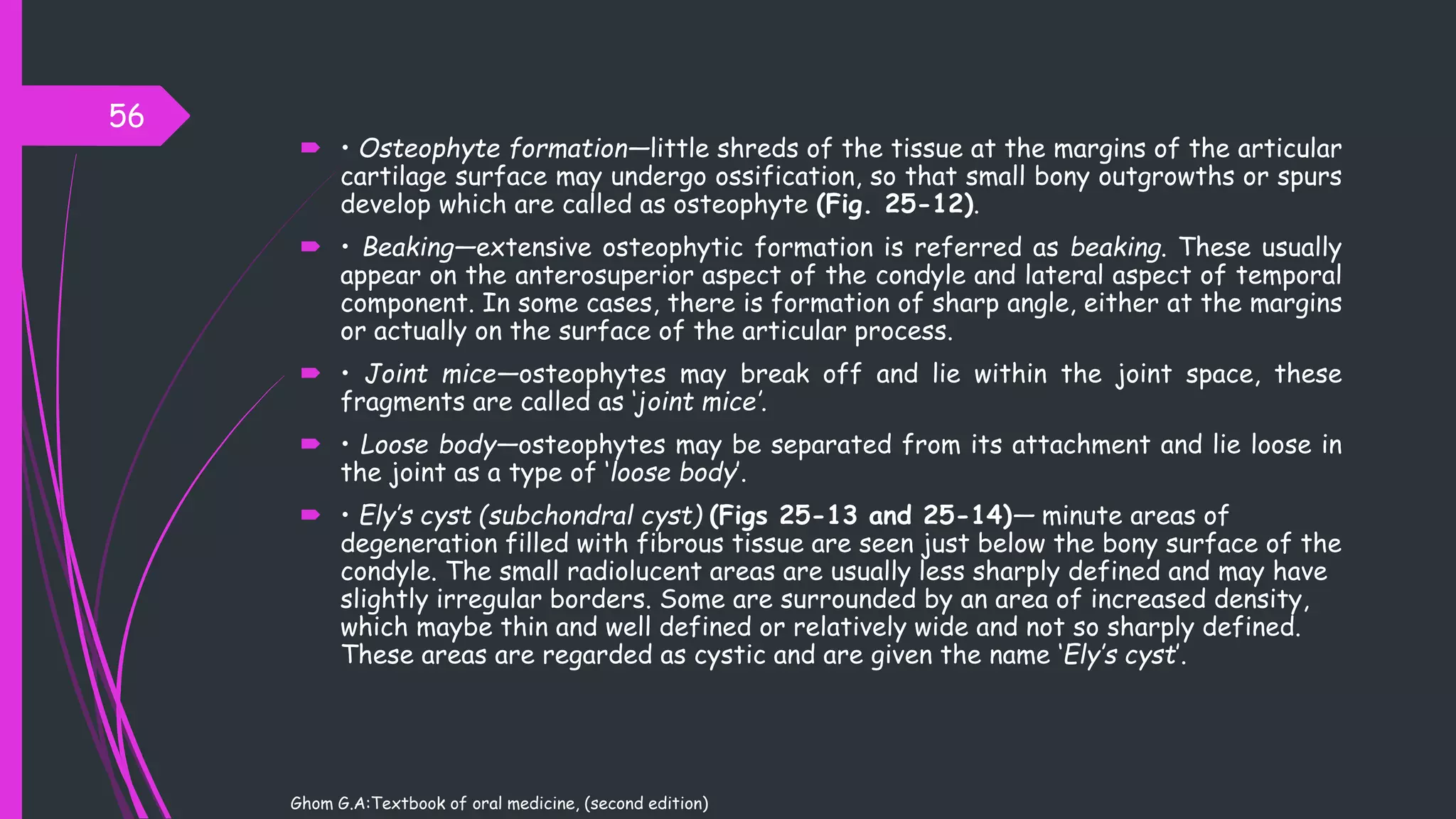

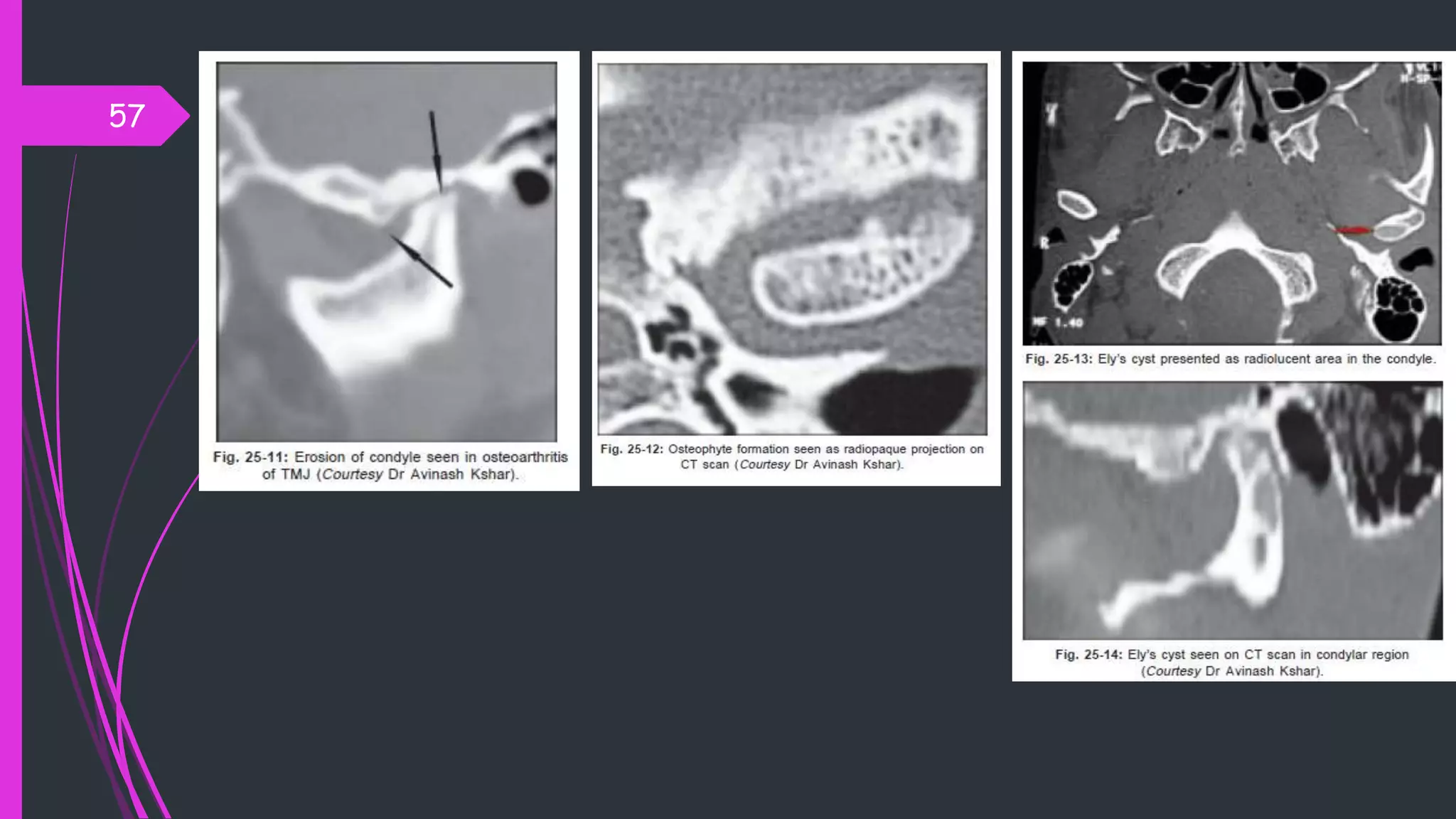

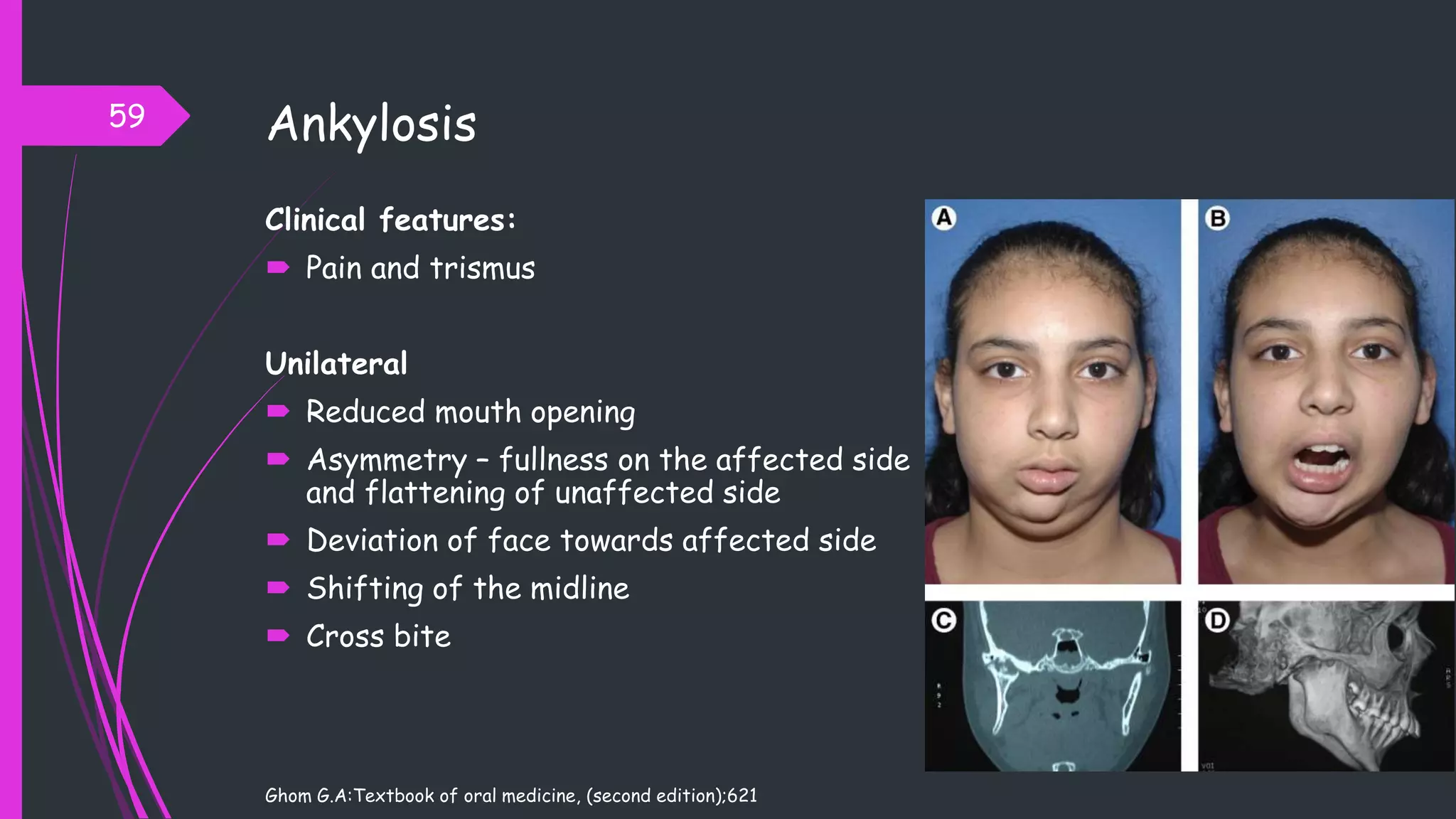

The document discusses occlusion and temporomandibular disorders. It begins with an introduction to the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) and its classification as a compound joint. The presentation then covers the anatomy of the TMJ including ligaments, muscles, the articular disc, movements, and examination. Common TMJ disorders are outlined such as hyperplasia and hypoplasia of the condyle. Treatment options for different disorders are mentioned. The document provides an overview of the structure, function and clinical aspects of the temporomandibular joint and disorders.

![ Findings are quite consistent towards a lack of clinically relevant association

between TMD and dental occlusion.

Only two (i.e., centric relation [CR]-maximum intercuspation [MI] slide and

mediotrusive interferences) of the almost fort occlusion features evaluated in

the various studies were associated with TMD in the majority (e.g., at least

50%) of single variable analyses in patient populations.

Only mediotrusive interferences are associated with TMD in the majority of

multiple variable analyses.

Such association does not imply a causal relationship and may even have

opposite implications than commonly believed (i.e., interferences being the

result, and not the cause, of TMD).

96

Manfredini D, Lombardo L, Siciliani G. Temporomandibular disorders and dental occlusion. A systematic review of association studies: end of

an era?. Journal of oral rehabilitation. 2017 Nov;44(11):908-23.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tmjseminarautosaved-230613161223-36bea22c/75/OCCLUSION-AND-TMDs-96-2048.jpg)