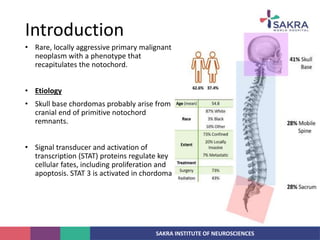

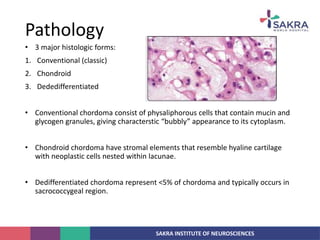

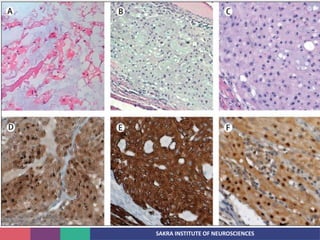

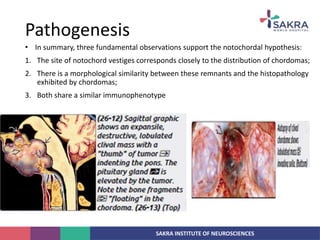

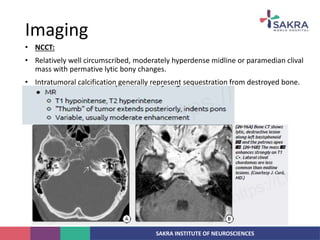

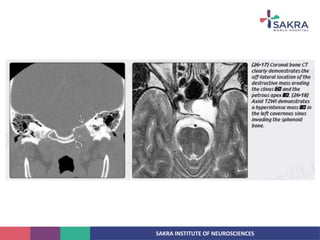

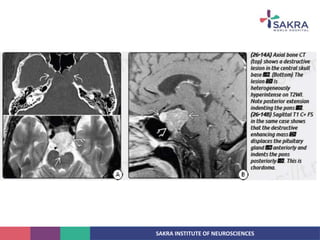

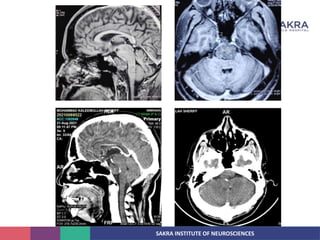

Chordoma is a rare malignant tumor originating from notochord remnants, primarily affecting the skull base and axial skeleton. The tumor presents three histological forms: conventional, chondroid, and dedifferentiated, each with distinct characteristics and clinical implications. Diagnosis is challenging due to variable presentations, and treatment often requires aggressive surgical intervention, with radiation therapy playing a critical role in management.