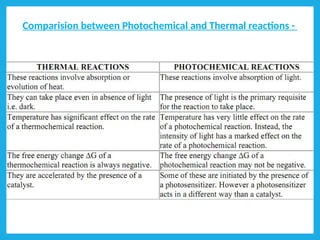

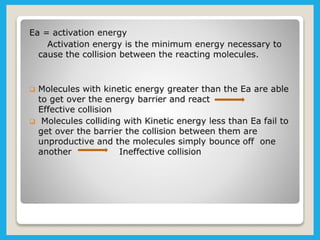

Chemical dynamics is a branch of physical chemistry that examines the rates and mechanisms of reactions, focusing on energy transfer at atomic scales. Key concepts include the Arrhenius equation, activation energy, and kinetic theories that describe how temperature and catalysts influence reaction rates. Additionally, the document covers chain reactions, steady-state kinetics, and the effects of ionic strength on reaction rates in solutions.

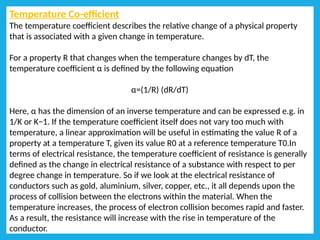

![The relation between temperature and resistances R0 and RT is

approximately given as:

RT=R0[1+α(T−T0)]

Hence, it is clear from the above equation that the change in

electrical resistance of any substance due to temperature depends

mainly on three factors:

• The value of resistance at an initial temperature.

• The rise in temperature.

• The temperature coefficient of resistance α.

The value of α can vary depending on the type of material.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chemicaldynamics-241207150525-74379240/85/Chemical-Dynamics-pptx-20-320.jpg)