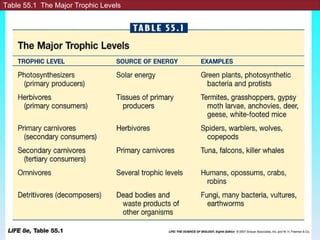

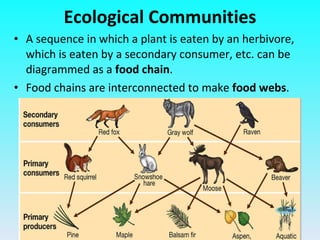

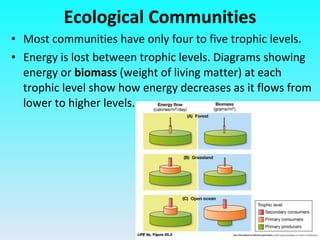

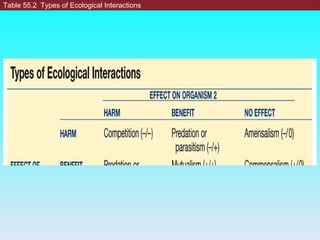

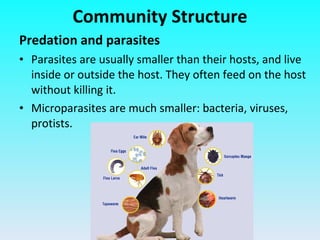

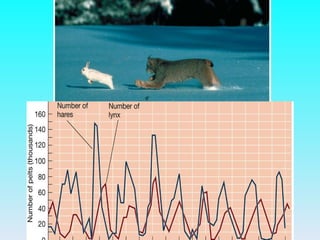

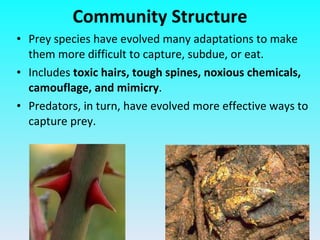

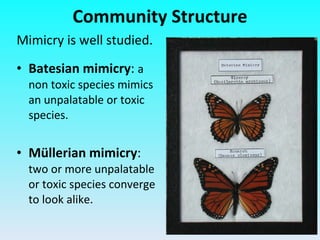

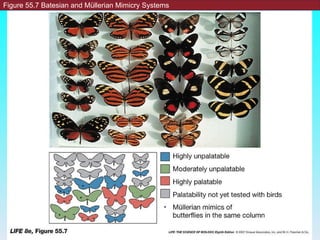

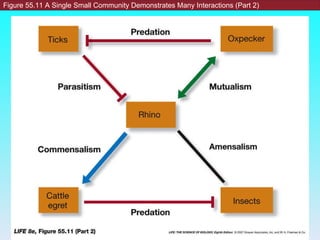

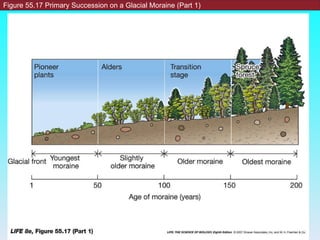

An ecological community consists of interacting species living in a given area. Organisms in a community can be divided into trophic levels based on how they obtain energy, such as primary producers obtaining energy from sunlight and heterotrophs obtaining energy from consuming primary producers. Ecological interactions between species within a community include predation, competition, mutualism, and others. Disturbances can alter community composition through succession as new species colonize or dominant species are removed.