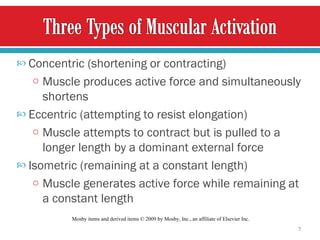

This lecture discusses the structure and function of skeletal muscle. It describes the different types of muscle contractions - concentric, eccentric, and isometric. It explains the sliding filament theory of muscle contraction and how cross-sectional area, shape, and line of pull determine a muscle's functional potential. It also describes how the length of a muscle affects its force production and discusses principles of stretching and strengthening muscle.