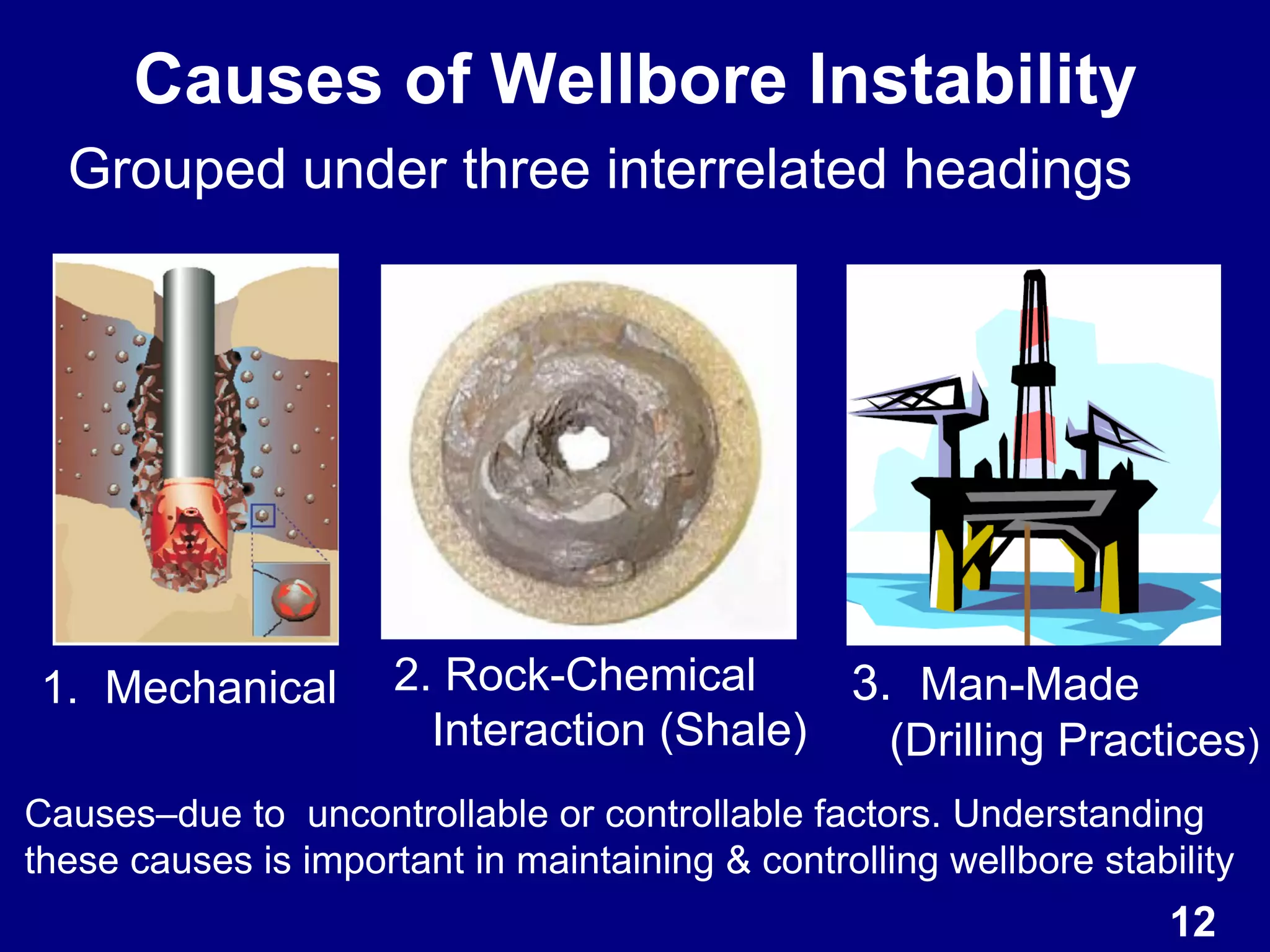

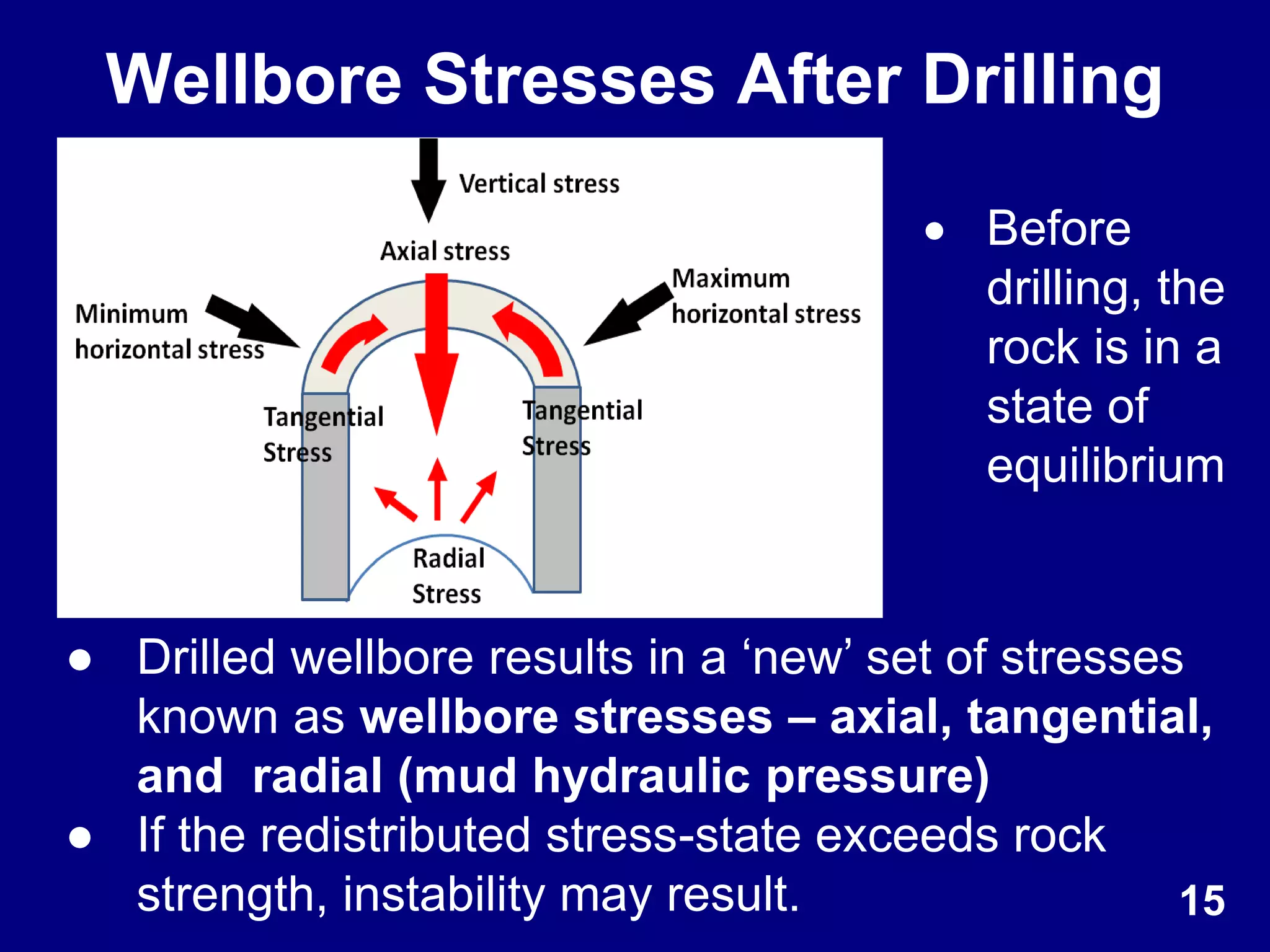

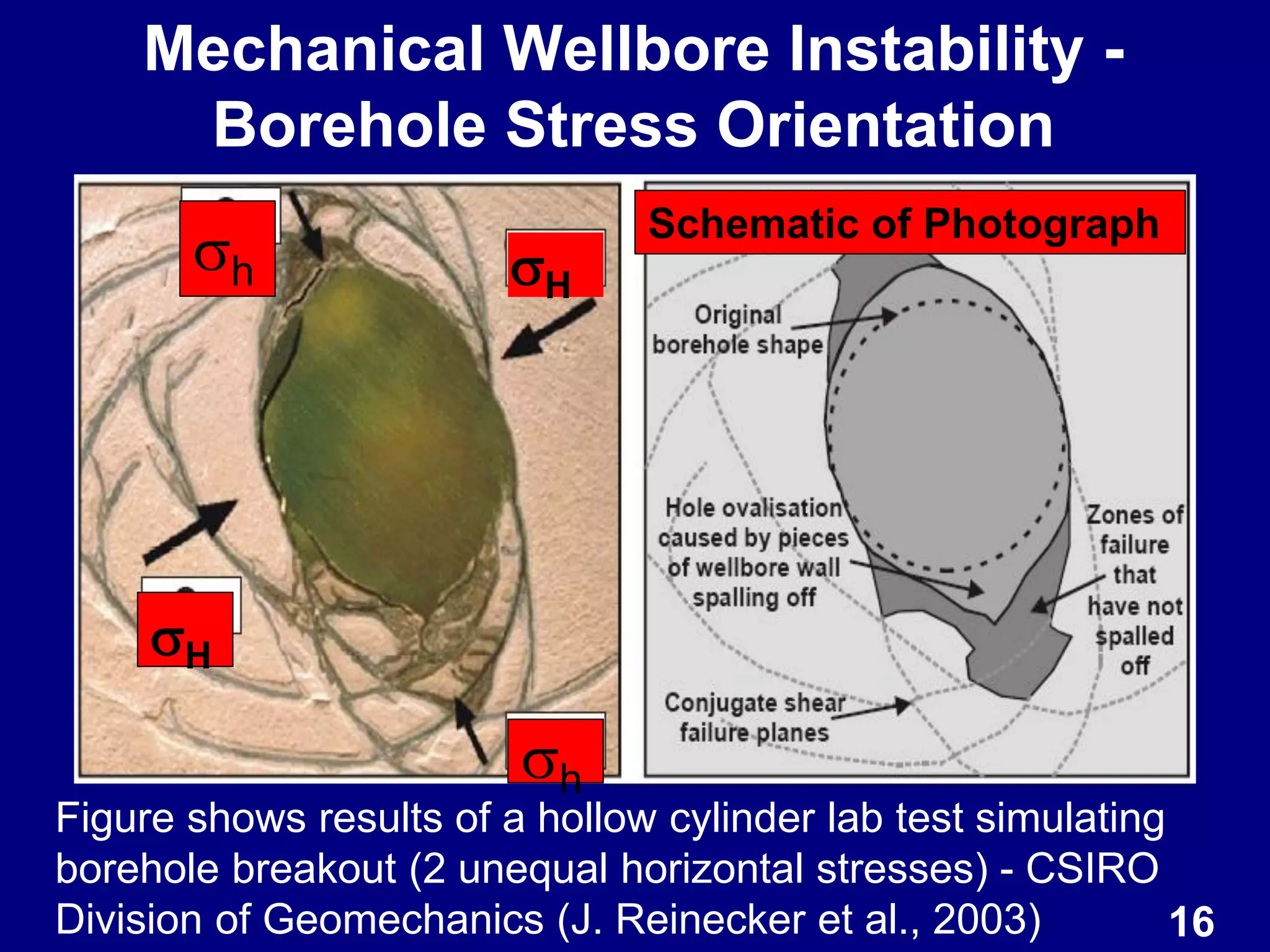

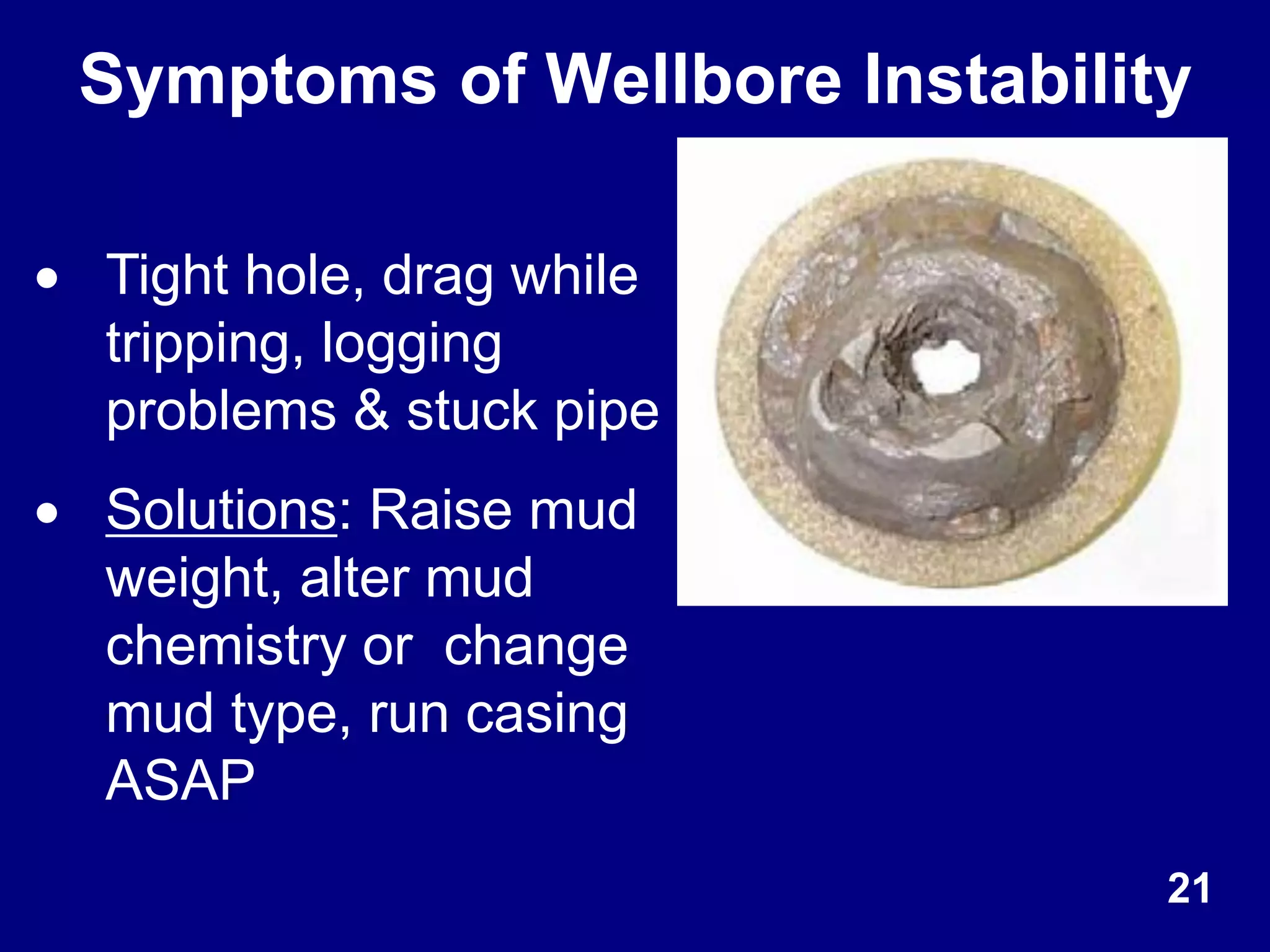

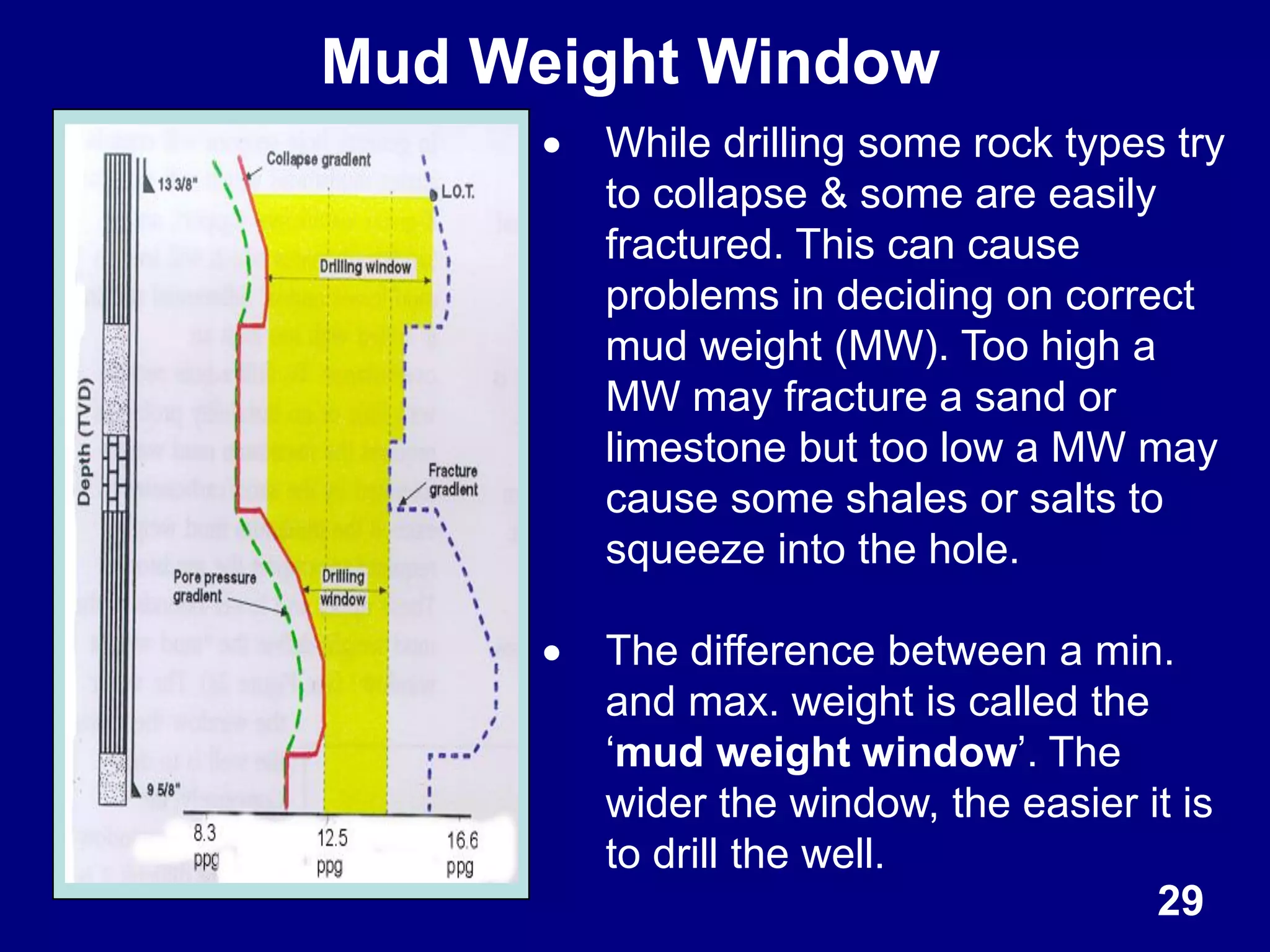

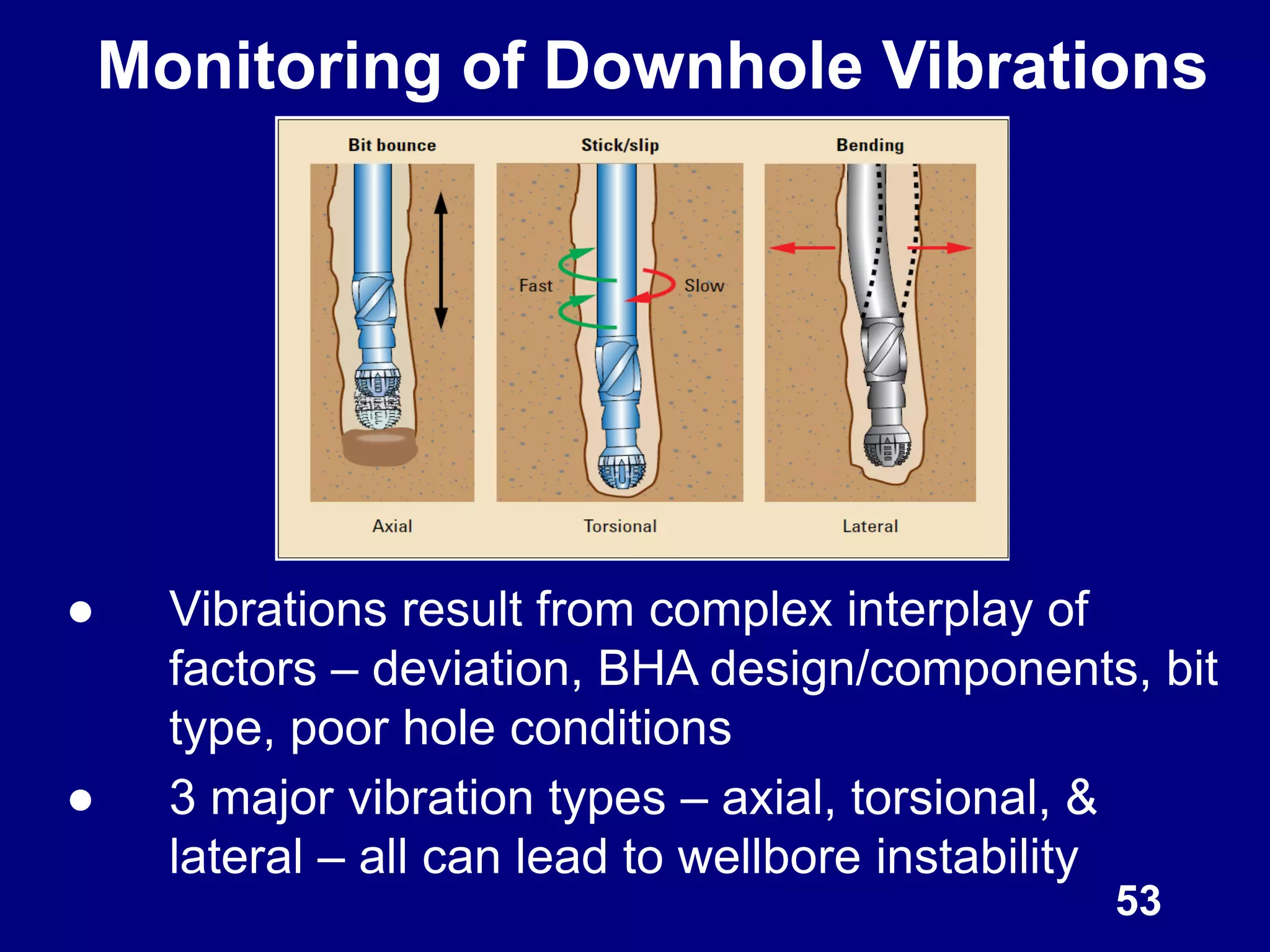

Wellbore instability can be caused by mechanical, chemical, and man-made factors. Remedial actions may include improving drilling practices to minimize pressure fluctuations, controlling mud weight, reducing drill string vibrations, and monitoring trends to detect instability early. Case studies demonstrate how applying integrated approaches, including geomechanical modeling and updated drilling plans, can help solve instability problems and prevent issues like stuck pipe.