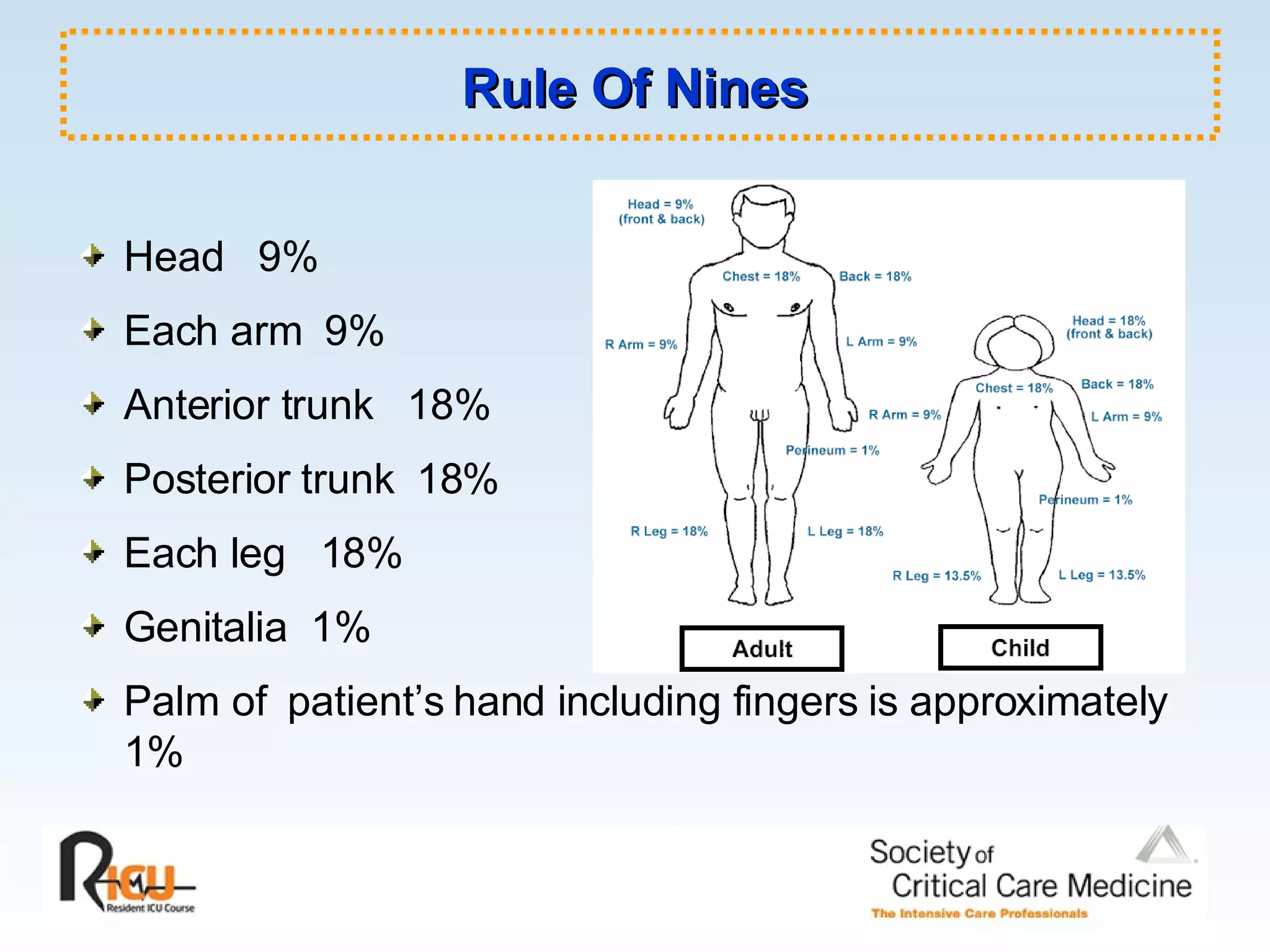

1. The document provides an overview of the initial assessment and resuscitation of severely burned patients, outlining considerations for airway management, fluid resuscitation, wound care, and monitoring. Burn severity is determined using the Rule of Nines and fluid resuscitation is guided by the Parkland formula.

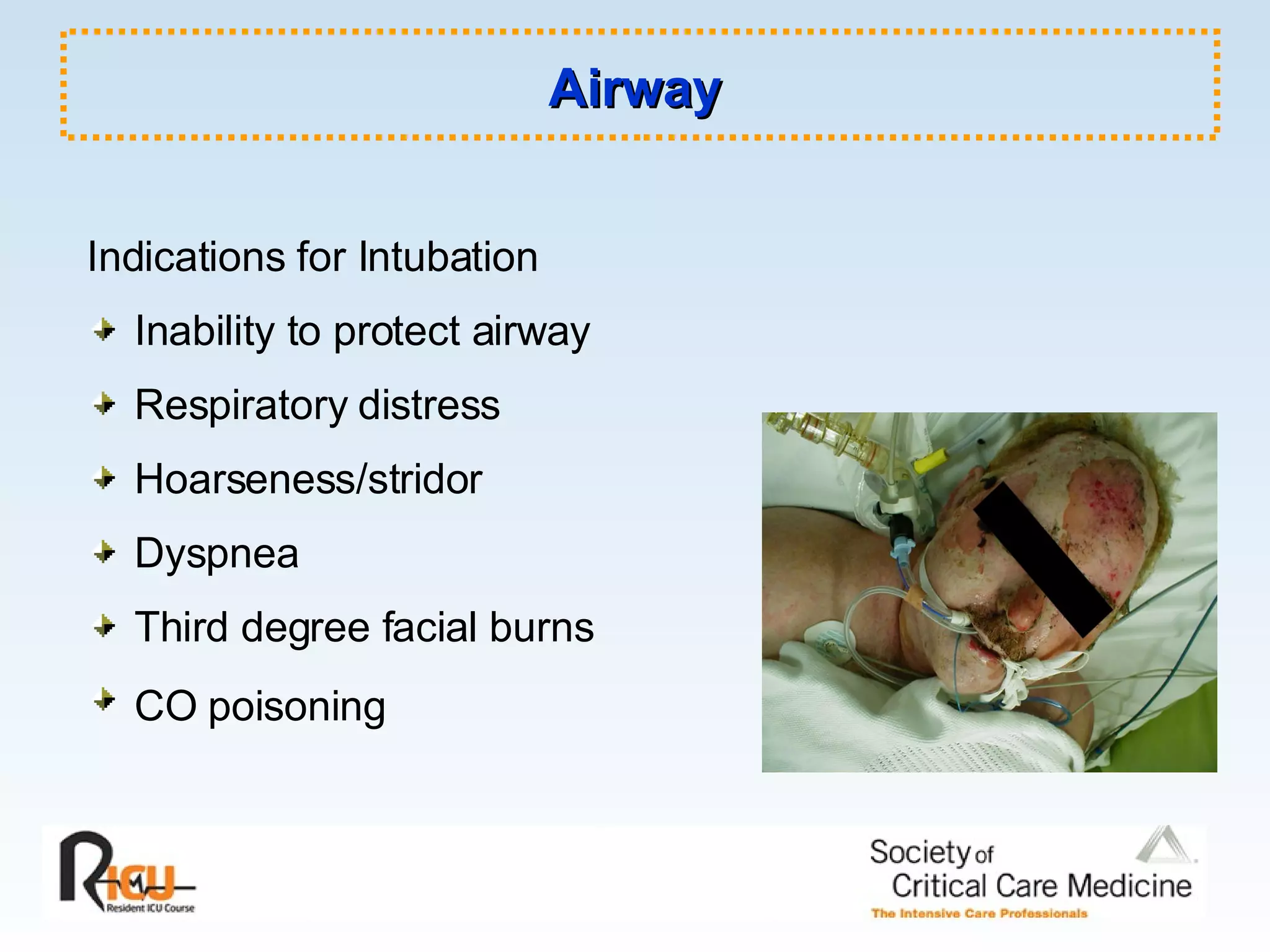

2. Smoke inhalation injuries require evaluation for intubation and treatment such as bronchodilators. Carbon monoxide poisoning is treated with high-flow oxygen and hyperbaric oxygen if needed.

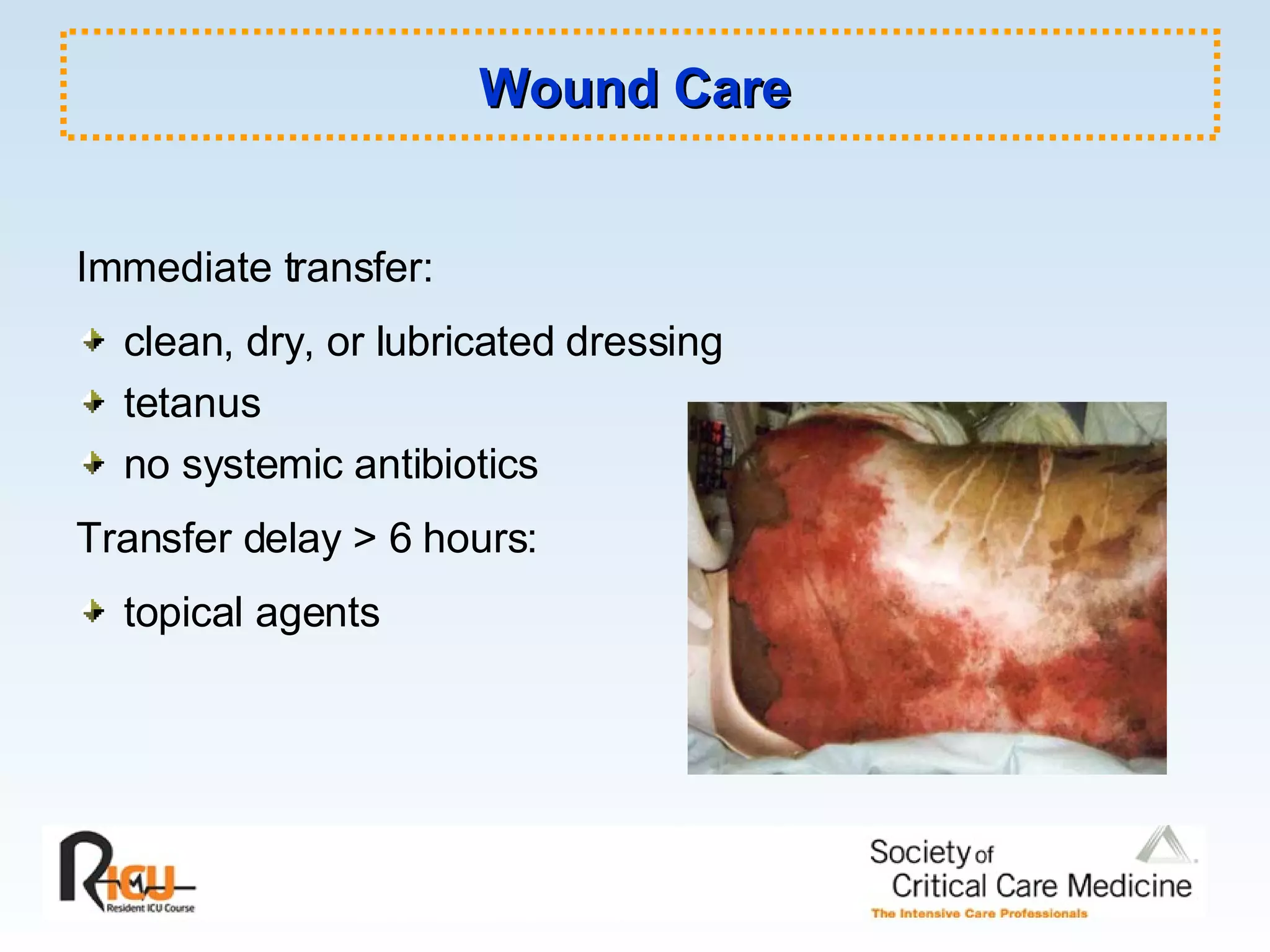

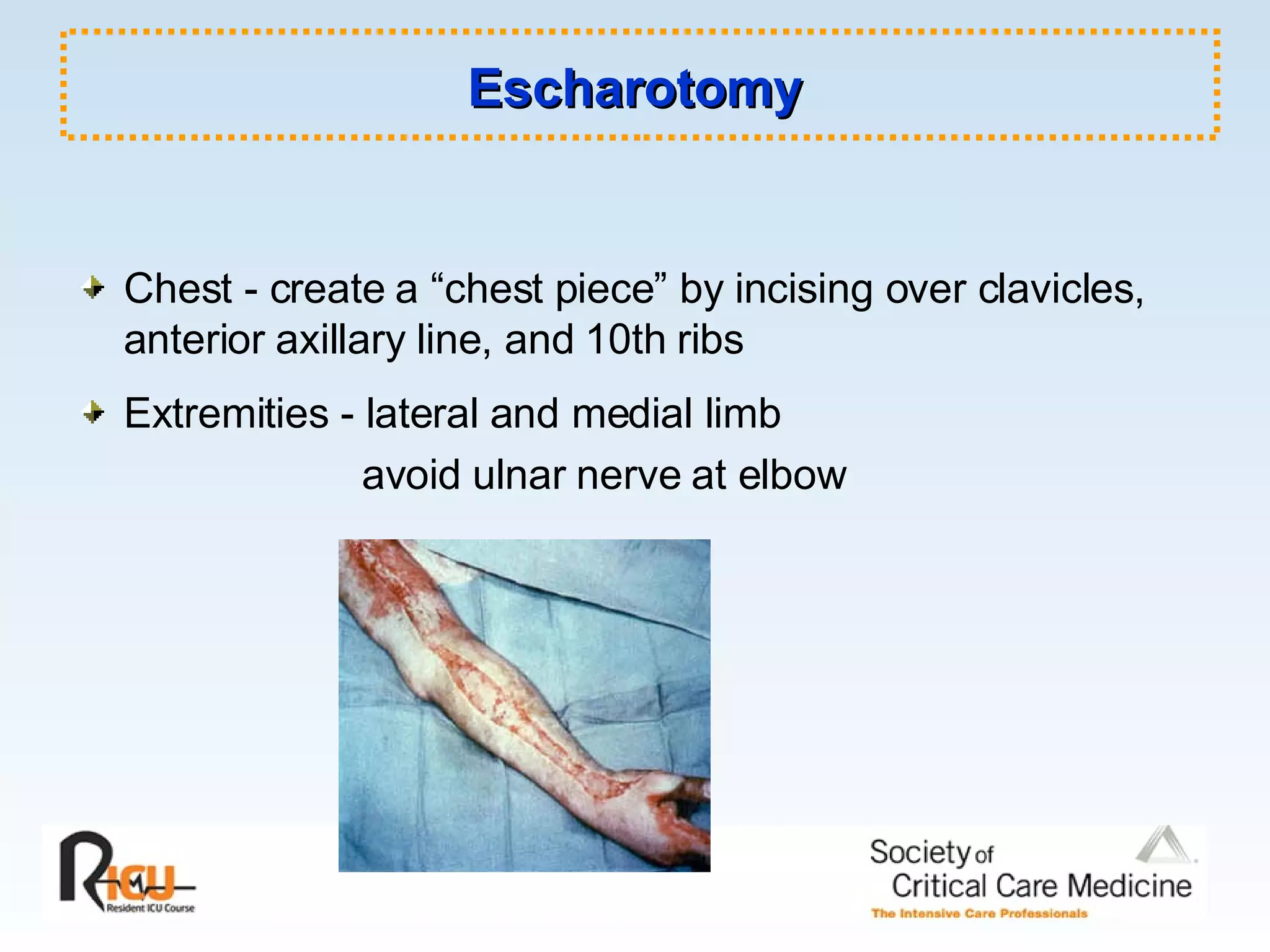

3. Wound care involves cleaning burns and applying topical antibiotics to reduce infection risks. Escharotomies are used to relieve pressure in circumferential burns. Electrical injuries carry cardiac and musculoskeletal risks