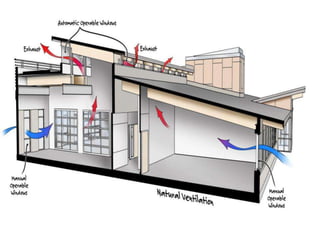

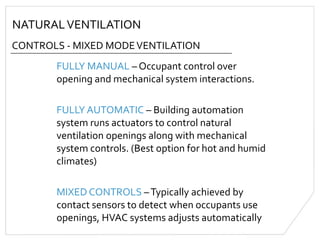

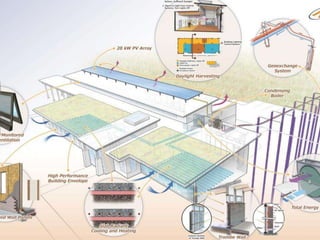

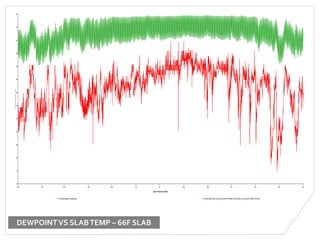

This document provides an overview of natural ventilation and hydronic cooling systems in humid climates like the Gulf Coast. It discusses human thermal comfort, natural ventilation approaches and benefits, mixed-mode ventilation, hydronic cooling system types like chilled beams, and design considerations for controlling humidity and moisture. The key advantages of these systems are energy savings when conditions allow for natural ventilation and more effective heat transfer through water-based systems. Controls integration and addressing humidity are important challenges.