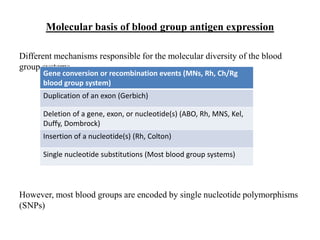

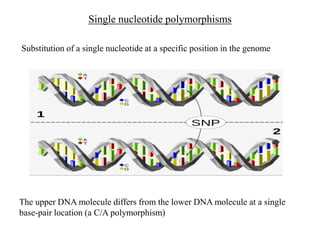

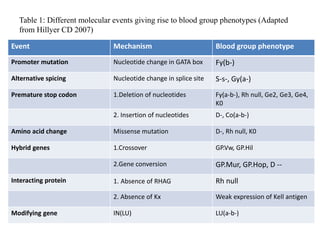

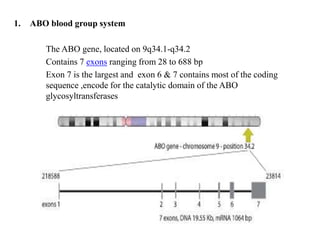

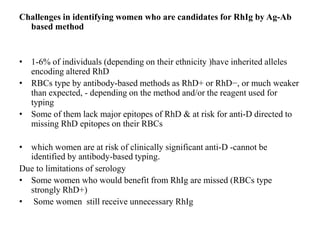

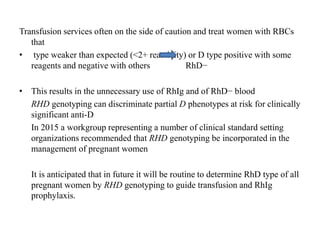

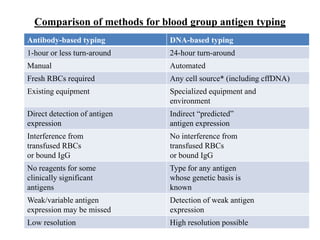

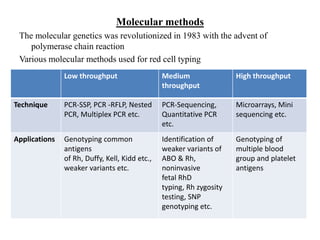

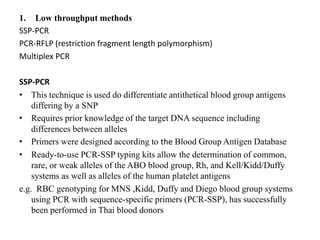

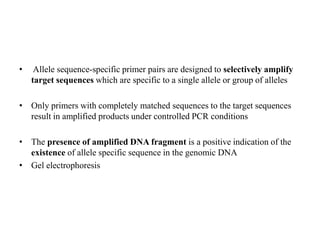

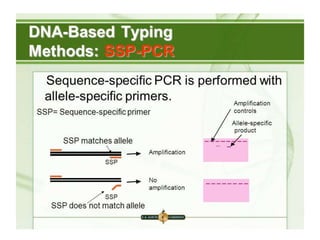

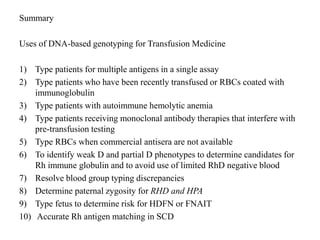

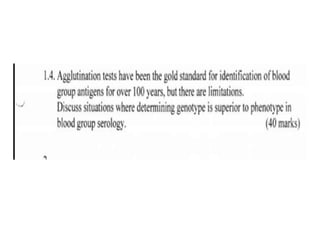

The document discusses the advancement of DNA-based genotyping in transfusion medicine as a substitute for traditional serological antibody methods, detailing how single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) contribute to blood group antigen diversity. It emphasizes the limitations of hemagglutination methods and the need for genotyping to improve blood type accuracy, particularly in patients with conditions like sickle cell disease and during prenatal testing. Furthermore, it highlights the importance of genotyping in enhancing donor compatibility and resolving discrepancies in blood typings.