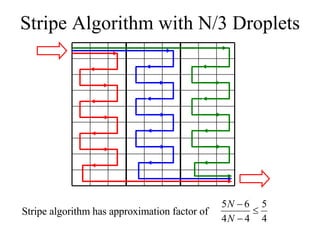

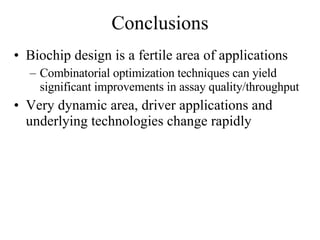

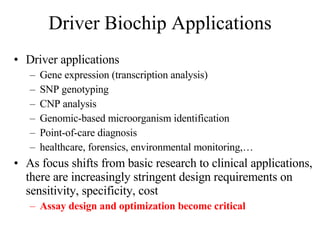

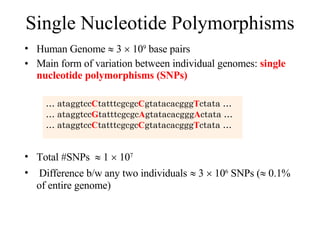

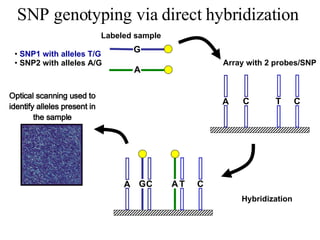

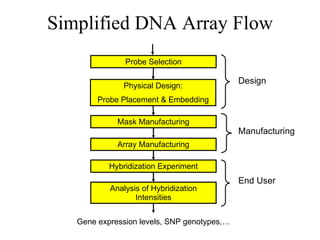

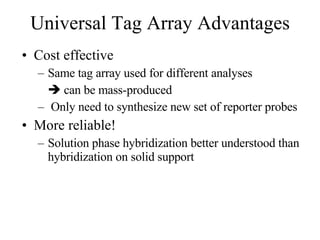

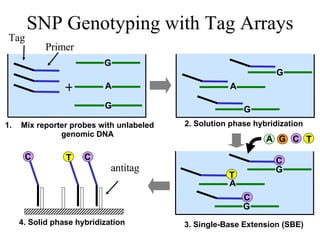

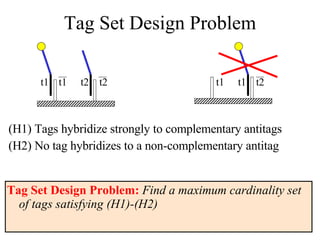

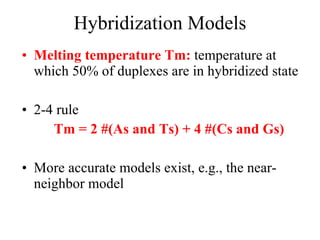

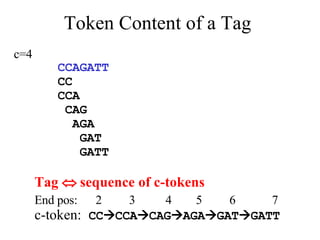

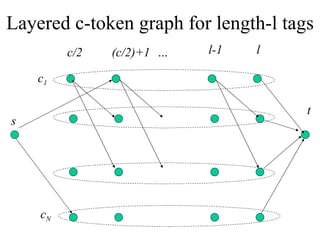

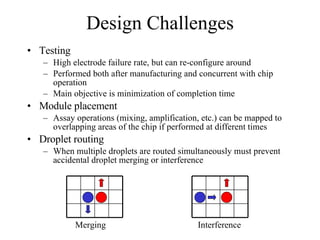

The document summarizes algorithms and techniques for biochip design and optimization. It discusses physical design of DNA arrays, tag set design for universal tag arrays, and algorithms to optimize concurrent testing on digital microfluidic biochips. Key applications include gene expression analysis, SNP genotyping, and point-of-care medical diagnosis. Design challenges involve minimizing border length in DNA arrays, maximizing tag set size while avoiding unwanted hybridization, and routing droplets on biochips to test for defects in minimal time without merging or interference.

![2D Placement: Sliding-Window Matching Slide window over entire chip Repeat fixed # of iterations ( O(N) time for fixed window size), or until improvement drops below certain threshold Proposed by [Doll et al. ‘94] in VLSI context 1 3 2 5 4 Select mutually nonadjacent probes from small window 2 2 3 1 4 Re-assign optimally](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/biochip-1216554436732982-9/85/Biochip-15-320.jpg)

![2D Placement: Epitaxial Growth Proposed by [PreasL’88, ShahookarM’91] in VLSI context Simulates crystal growth Efficient “row” implementation Use lexicographical sorting for initial ordering of probes Fill cells row-by-row Bound number of candidate probes considered when filling each cell Constant # of lookahead rows O(N 3/2 ) runtime, N = #probes](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/biochip-1216554436732982-9/85/Biochip-16-320.jpg)

![2D Placement: Recursive Partitioning Very effective in VLSI placement [AlpertK’95,Caldwell et al.’00] 4-way partition using linear time clustering Repeat until Row-Epitaxial can be applied](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/biochip-1216554436732982-9/85/Biochip-17-320.jpg)

![Hamming distance model, e.g., [Marathe et al. 01] Models rigid DNA strands LCS/edit distance model, e.g., [Torney et al. 03] Models infinitely elastic DNA strands c-token model [Ben-Dor et al. 00]: Duplex formation requires formation of nucleation complex between perfectly complementary substrings Nucleation complex must have weight c, where wt(A)=wt(T)=1, wt(C)=wt(G)=2 (2-4 rule) Hybridization Models (contd.)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/biochip-1216554436732982-9/85/Biochip-28-320.jpg)

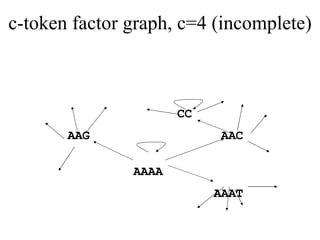

![c-h Code Problem c-token: left-minimal DNA string of weight c, i.e., w(x) c w(x’) < c for every proper suffix x’ of x A set of tags is a c-h code if (C1) Every tag has weight h (C2) Every c-token is used at most once c-h Code Problem [Ben-Dor et al.00] Given c and h, find maximum cardinality c-h code](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/biochip-1216554436732982-9/85/Biochip-29-320.jpg)

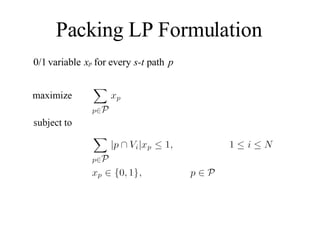

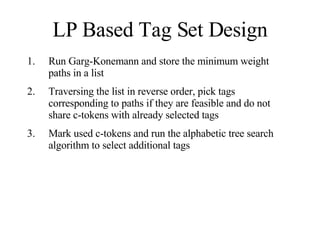

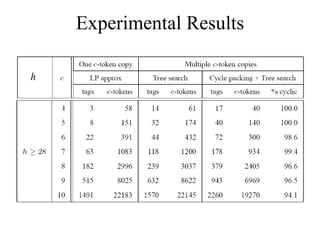

![Algorithms for c-h Code Problem [Ben-Dor et al.00] approximation algorithm based on DeBruijn sequences Alphabetic tree search algorithm Enumerate candidate tags in lexicographic order, save tags whose c-tokens are not used by previously selected tags Easily modified to handle various combinations of constraints [MT 05, 06] Optimum c-h codes can be computed in practical time for small values of c by using integer programming Practical runtime using Garg-Koneman approximation and LP-rounding](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/biochip-1216554436732982-9/85/Biochip-30-320.jpg)

![Integer Program Formulation [MPT05] Maximum integer flow problem w/ set capacity constraints O( hN) constraints & variables, where N = #c-tokens](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/biochip-1216554436732982-9/85/Biochip-33-320.jpg)

![Garg-Konemann Algorithm x 0; y // y i are variables of the dual LP Find min weight s-t path p, where weight(v) = y i for every v V i While weight(p) < 1 do M max i |p V i | x p x p + 1/M For every i, y i y i ( 1 + * |p V i |/M ) Find min weight s-t path p, where weight(v) = y i for v V i 4. For every p, x p x p / (1 - log 1+ ) [GK98] The algorithm computes a factor (1- ) 2 approximation to the optimal LP solution with (N/ )* log 1+ N shortest path computations](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/biochip-1216554436732982-9/85/Biochip-35-320.jpg)

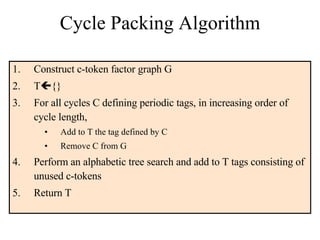

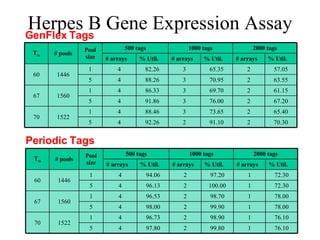

![Periodic Tags [MT05] Key observation: c-token uniqueness constraint in c-h code formulation is too strong A c-token should not appear in two different tags, but can be repeated in a tag A tag t is called periodic if it is the prefix of ( ) for some “period” Periodic strings make best use of c-tokens](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/biochip-1216554436732982-9/85/Biochip-37-320.jpg)

![Vertex-disjoint Cycle Packing Problem Given directed graph G, find maximum number of vertex disjoint directed cycles in G [MT 05] APX-hard even for regular directed graphs with in-degree and out-degree 2 h-c/2+1 approximation factor for tag set design problem [Salavatipour and Verstraete 05] Quasi-NP-hard to approximate within (log 1- n) O(n 1/2 ) approximation algorithm](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/biochip-1216554436732982-9/85/Biochip-39-320.jpg)

![More Hybridization Constraints… Enforced during tag assignment by - Leaving some tags unassigned and distributing primers across multiple arrays [Ben-Dor et al. 03] - Exploiting availability of multiple primer candidates [MPT05] t1 t2 t1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/biochip-1216554436732982-9/85/Biochip-42-320.jpg)

![Digital Microfluidic Biochips [Srinivasan et al. 04] Electrodes typically arranged in rectangular grid Droplets moved by applying voltage to adjacent cell Can be used for analyses of DNA, proteins, metabolites… [Su&Chakrabarty 06] I/O I/O Cell](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/biochip-1216554436732982-9/85/Biochip-45-320.jpg)

![Concurrent Testing Problem GIVEN: Input/Output cells Position of obstacles (cells in use by ongoing reactions) FIND: Trajectories for test droplets such that Every non-blocked cell is visited by at least one test droplet Droplet trajectories meet non-merging and non-interference constraints Completion time is minimized Defect model: test droplet gets stuck at defective electrode [Su et al. 04] ILP-based solution for single test droplet case & heuristic for multiple input-output pairs with single test droplet/pair](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/biochip-1216554436732982-9/85/Biochip-47-320.jpg)