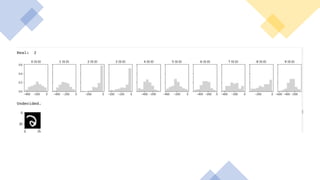

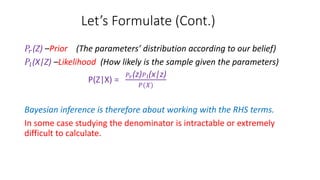

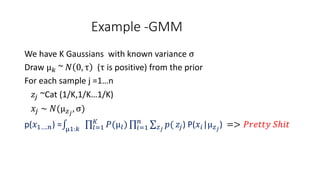

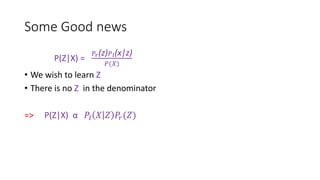

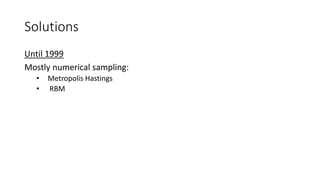

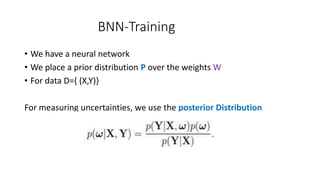

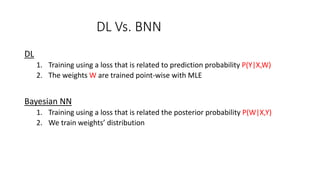

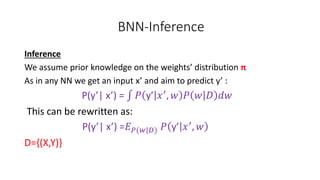

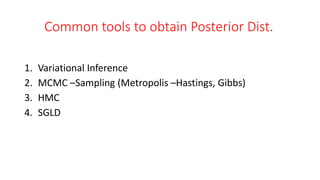

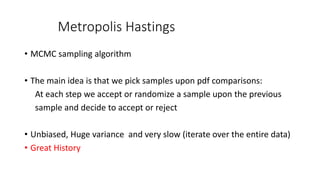

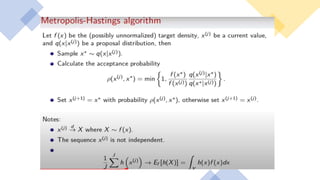

This document discusses Bayesian neural networks. It begins with an introduction to Bayesian inference and variational inference. It then explains how variational inference can be used to approximate the posterior distribution in a Bayesian neural network. Several numerical methods for obtaining the posterior distribution are covered, including Metropolis-Hastings, Hamiltonian Monte Carlo, and Stochastic Gradient Langevin Dynamics. Finally, it provides an example of classifying MNIST digits with a Bayesian neural network and analyzing model uncertainties.

![VI – Algorithm Overview

• Rather a numerical sampling method we provide an analytical one:

1. We define a distribution family Q(Z) (bias-variance trade off)

2. We minimize KL divergence min KL(Q(z)|| P(Z|X))

log(P(X)) = 𝐸 𝑄 [log P(x, Z)] − 𝐸 𝑄 [log Q(Z)] + KL(Q(Z)||P(Z|X))

ELBO-Evidence Lower Bound

• Maximizing ELBO =>minimizing KL](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bnn6-201217144233/85/Bayesian-Neural-Networks-12-320.jpg)

![𝐸𝐿𝐵𝑂 = 𝐸 𝑄[log P(X, Z)] − 𝐸 𝑄 [log Q(Z)] = 𝑄𝐿𝑜𝑔(

𝑃(𝑋,𝑍)

𝑄(𝑍)

)= J(Q)- Euler Lagrange

MFT (Mean Field Theory)

Scientific “approval”

13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bnn6-201217144233/85/Bayesian-Neural-Networks-13-320.jpg)

![Measuring Uncertainty

• In the inference, given a data point 𝑥∗

• Sample weights W 𝑛 𝑡𝑖𝑚𝑒𝑠

• Calculate its statistics

E[f(𝑥∗

,w)]= 𝑖=1

𝑛

𝑓(𝑥∗

, 𝑤𝑖)

V([f(𝑥∗

,w)] =E𝑓(𝑥∗

,w)2

- E[f(𝑥∗

,w)]2

W –r.v. which 𝑤𝑖 is its samples](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bnn6-201217144233/85/Bayesian-Neural-Networks-28-320.jpg)

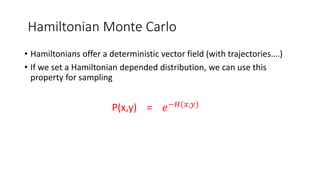

![What is Hamiltonian?

• A physical operator that measures energy of a dynamical system

Two sets of coordinates

q -State coordinates

p- Momentum

H(p, q) =U(q) +K(p)

U(q) = log[π 𝑞 𝐿(𝑞|𝐷)] K(P)=

𝑝 2

2𝑚

U-Potential energy, K –Kinetic

𝑑𝐻

𝑑𝑝

= 𝑞 ,

𝑑𝐻

𝑑𝑞

= - 𝑝](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bnn6-201217144233/85/Bayesian-Neural-Networks-32-320.jpg)

![Robbins & Monro (Stoch. Approx. 1951)

• Let F a function and θ a number

• There exists a unique solution :

F(𝑥∗ ) = θ

F - is unknown

Y - A measurable r.v.

E[Y(x)] = F(x)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bnn6-201217144233/85/Bayesian-Neural-Networks-43-320.jpg)