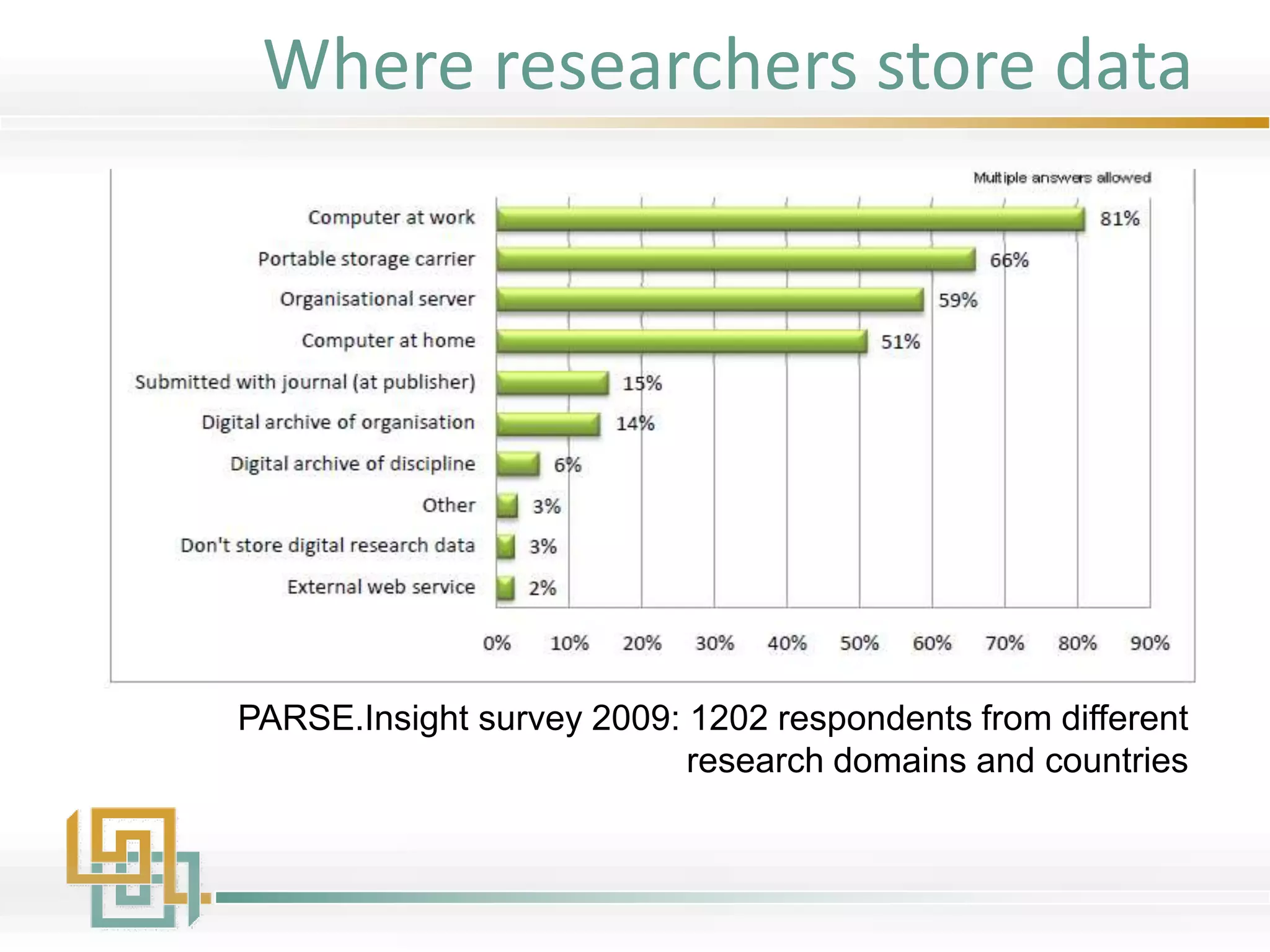

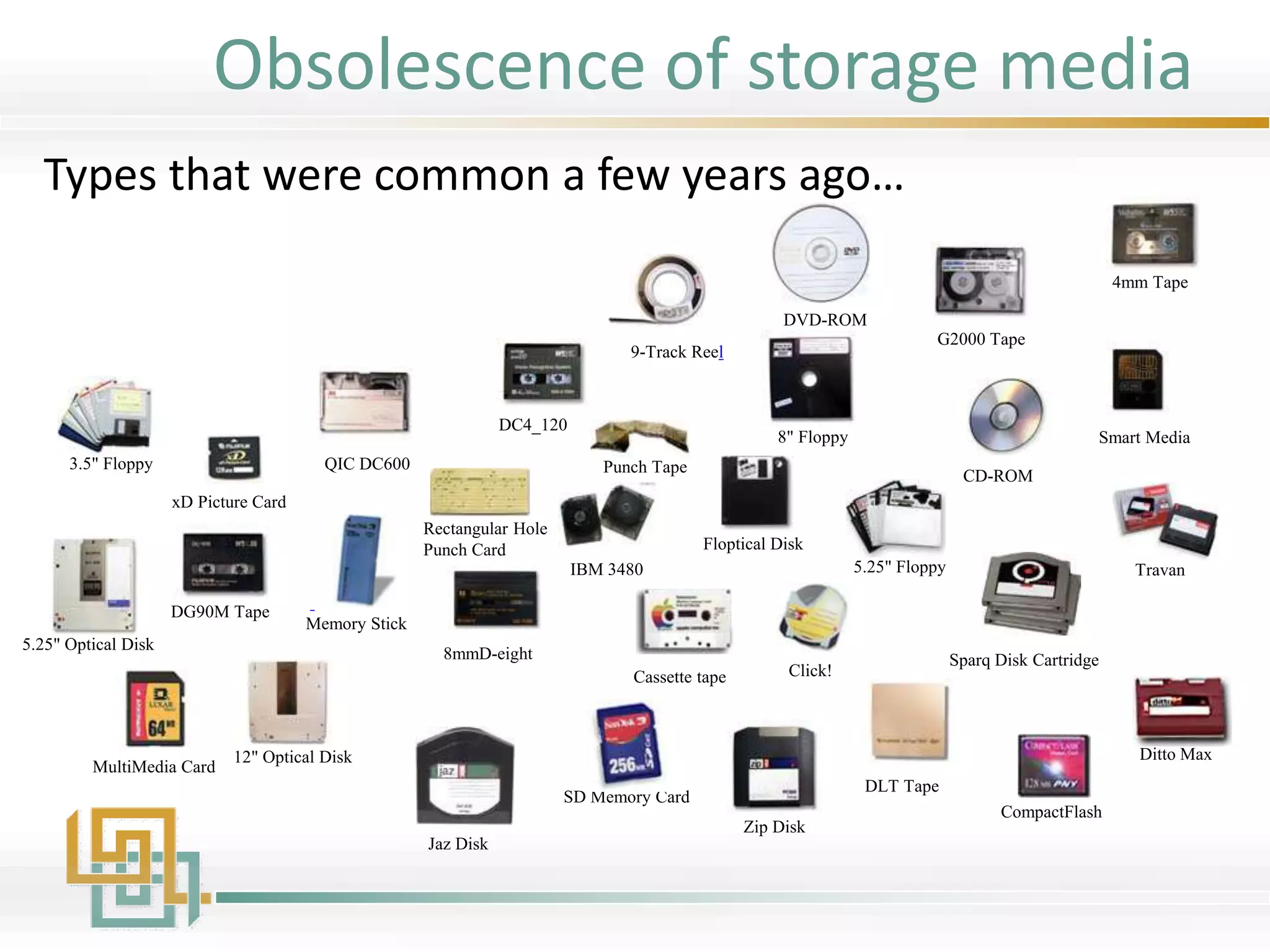

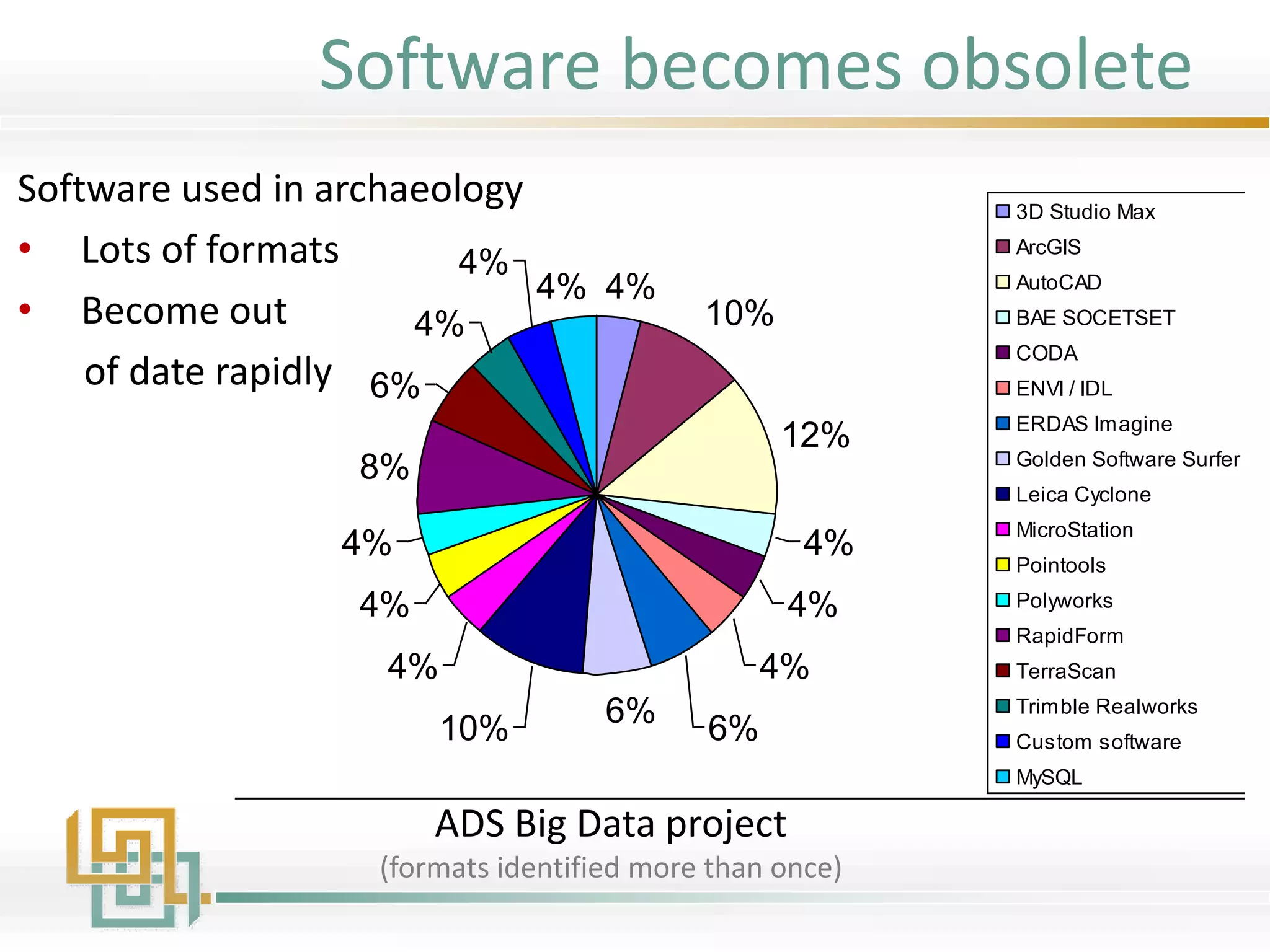

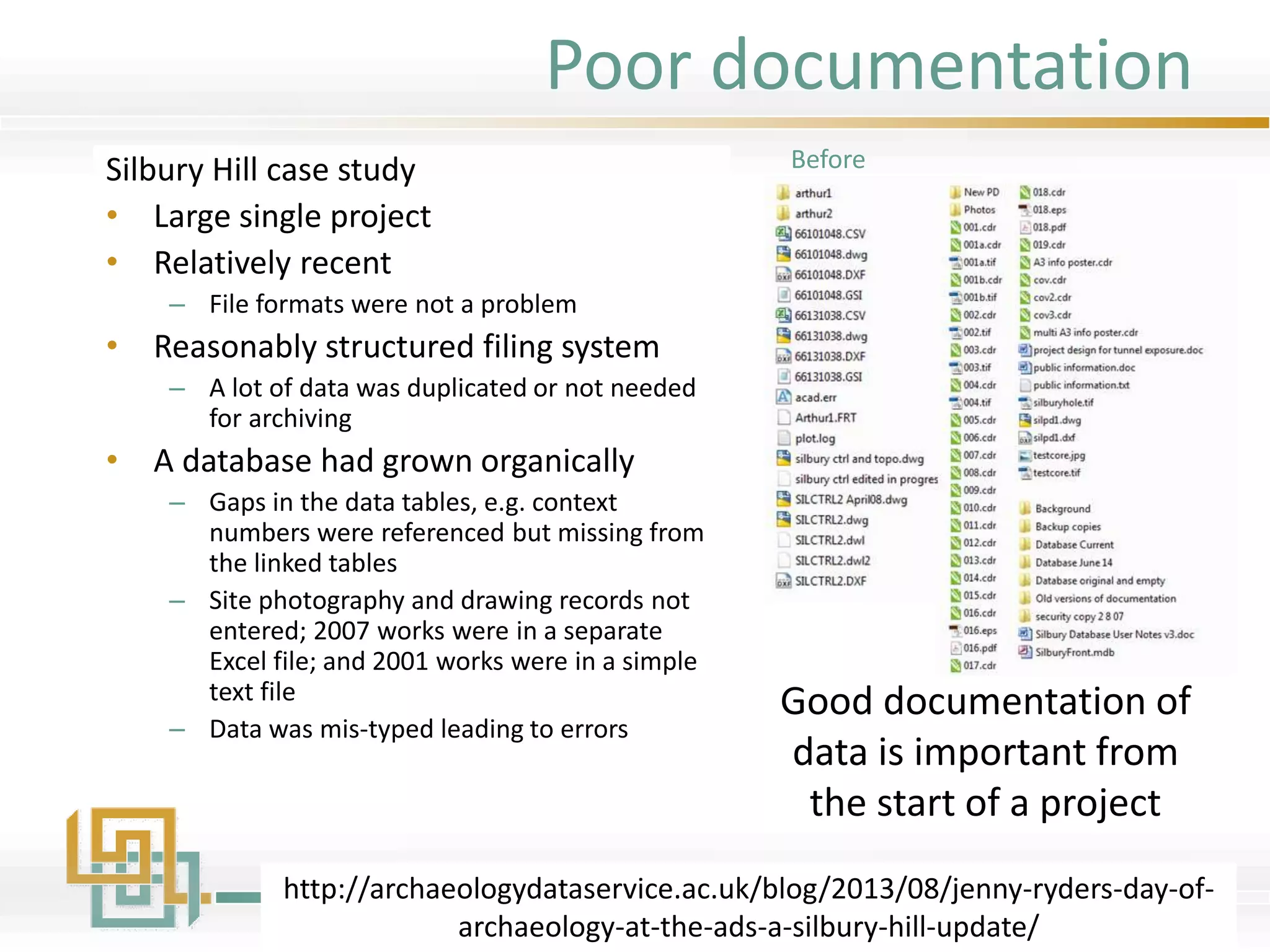

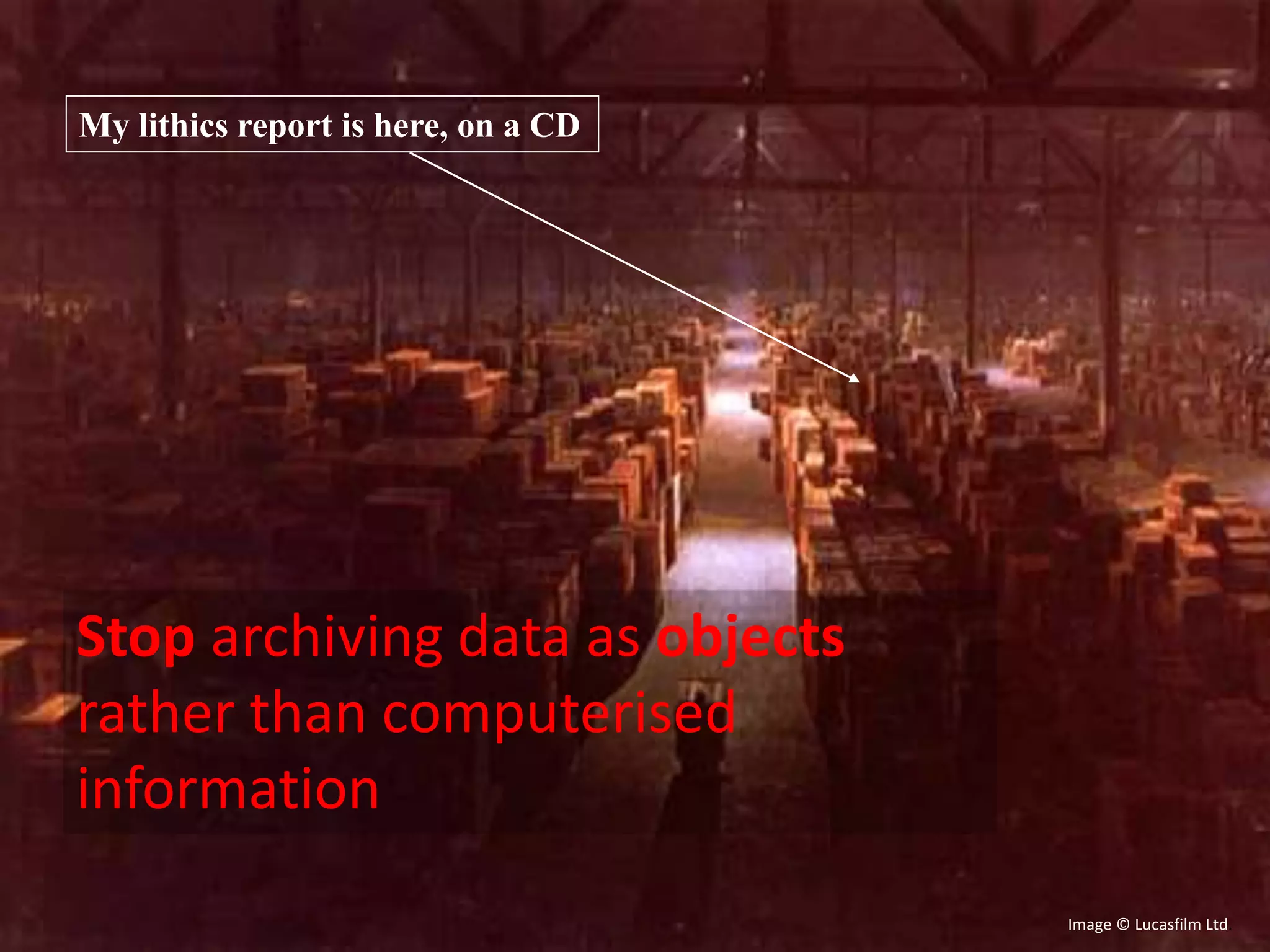

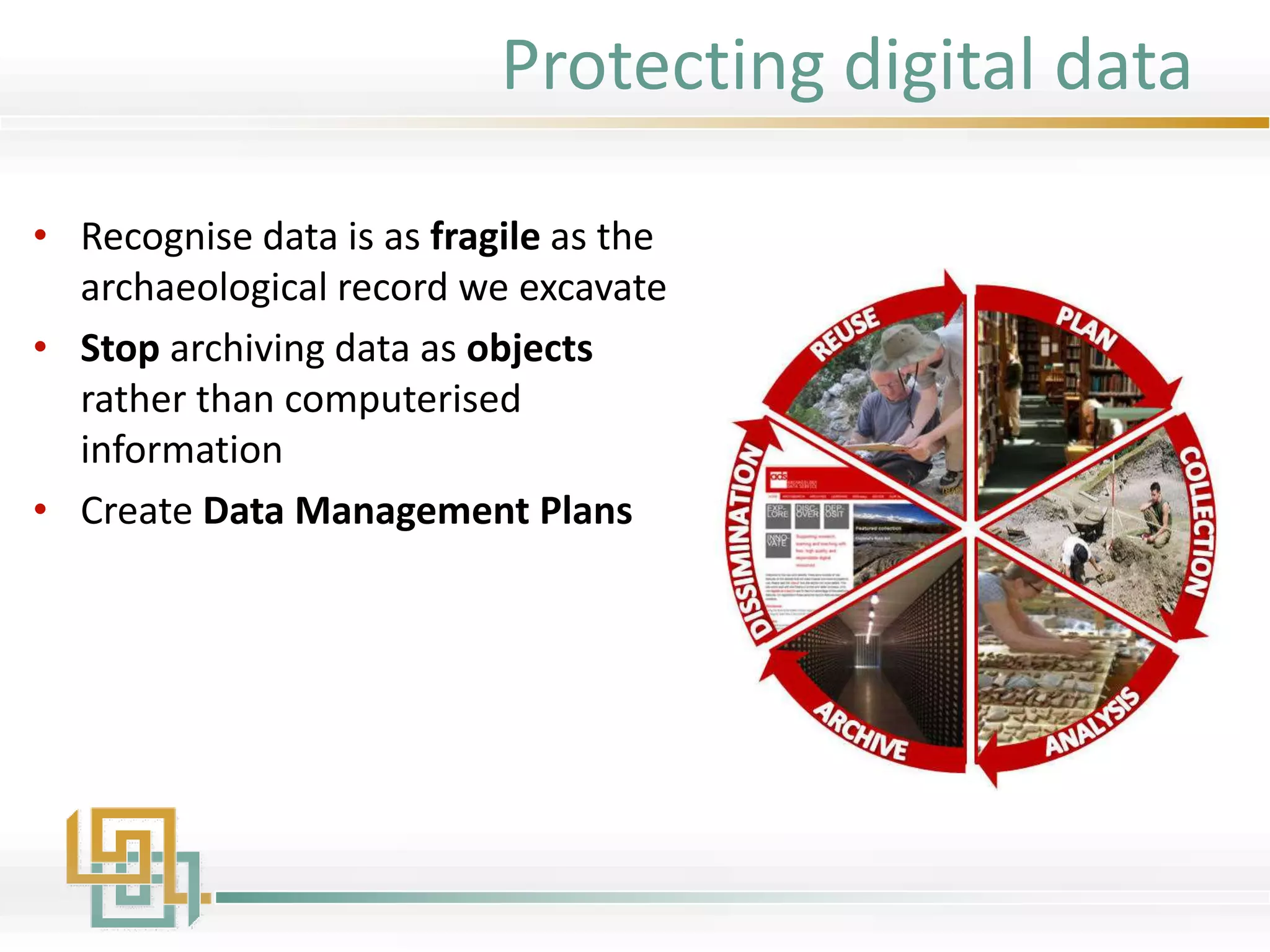

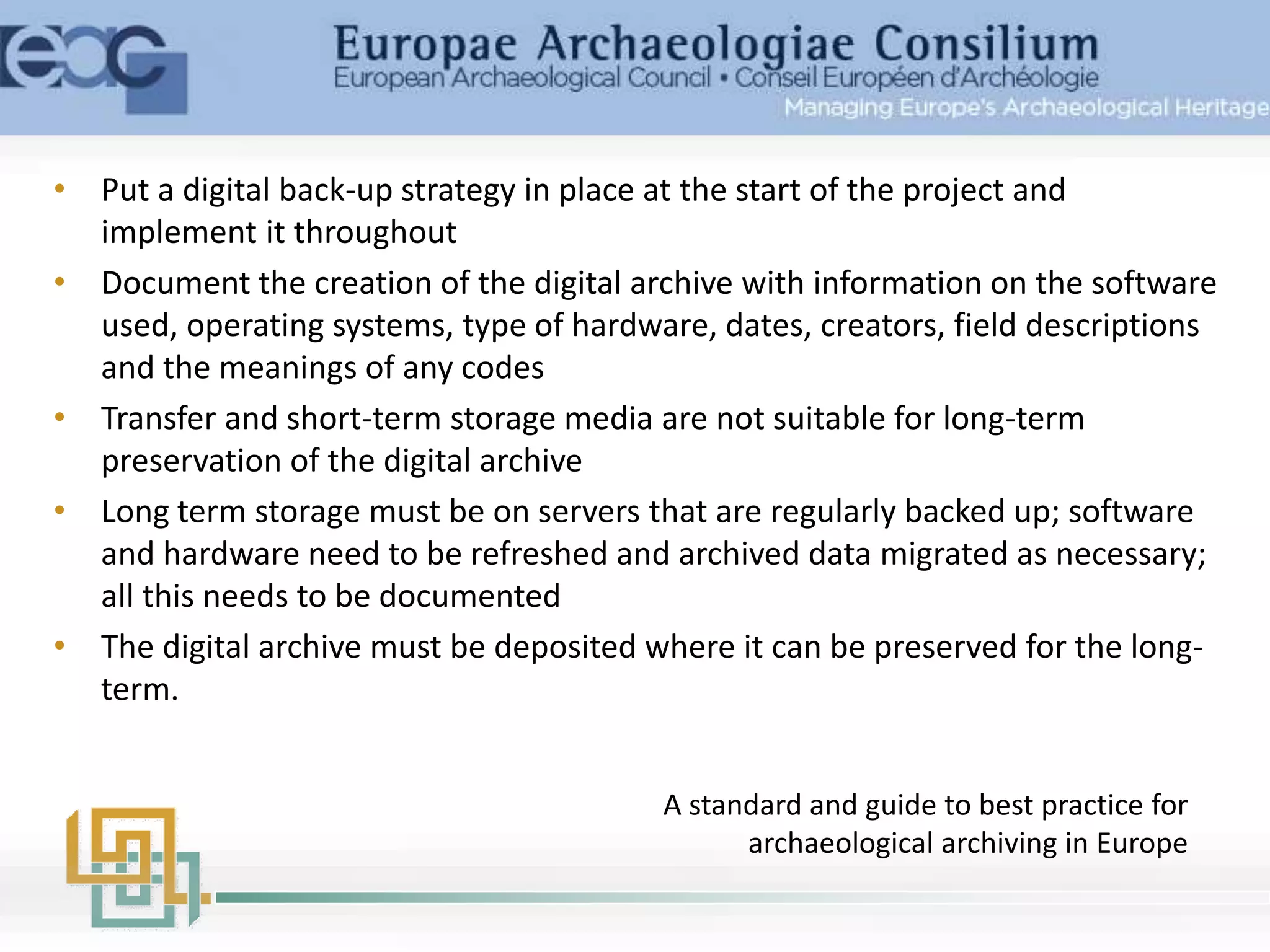

Ariadne is an EU-funded infrastructure project designed to integrate archaeological research data infrastructures, enabling researchers to access and utilize distributed datasets. The document stresses the importance of preserving digital data due to its fragility and the impermanence of storage media and software. It emphasizes the need for effective data management plans and long-term storage solutions to safeguard valuable archaeological records.