The document is the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia's annual report on human rights in Serbia in 2011. Some of the key points made in the report include:

- Serbia's movement towards EU integration depends on its dialogue with Kosovo and implementing existing agreements, as its policies on Kosovo and the region are currently at a dead end.

- Transitional justice has not substantially progressed, and factors contributing to instability in neighboring countries like Bosnia remain.

- Civil society lacks sufficient participation in decision-making and political processes.

- Serbia's political elite is trapped in the past and role-playing the victim, preventing constructive work on Serbia's future and relations with neighbors.

- Russia's influence disorients

![60 serbia 2011 : Introduct

i

on

Nataša Kandić was again threatened with a criminal complaint instead

of launching a serious public debate on the contents of the document in

which Diković is accused of indirect participation in serious crimes against

civilian population.

The weekly Pečat has been at the forefront of the anti-NGO cam-

paign ever since its establishment. In its attacks on NGOs, the weekly re-

lies chiefly on its journalist Nikola Vrzić, a ‘conspiracy theorist’ who shot

to prominence while working for the weekly NIN during the term of Vojis-

lav Koštunica as prime minister. Vrzić is best remembered for a series of

articles about the assassination of prime minister Zoran Đinđić: his third-

bullet or ‘ice-bullet’ theory (suggesting there was another shooter on the

scene) put him on the side of a group trying to discredit the trial of the

people charged with Đinđić’s murder. Vrzić’s attitude is best illustrated by

an article published in Pečat No 163 in 2011. In the article entitled ‘How to

Change the Serb Psyche’, he analyses the work of the Belgrade Centre for

Human Rights or more specifically its 2010 report. In the article brimming

with insults, he sets out the following thesis under the sub-title ‘CIA and

NGOS’. He alleges that the Belgrade Centre for Human Rights is financed

by ‘[...] Freedom House and the National Endowment for Democracy, US

non-governmental organizations well known for their connections with

the US Administration, the US Army and the Central Intelligence Agency

(CIA) [...] so let’s see who is praised and who is criticized in the 2010 report

of the Belgrade Centre for Human Rights that is financed in this way [...]’.93

Articles of this kind, which have been churned out routinely for nearly 20

years, are forever on the lookout for the enemy, in particular the enemy

within. The example given above shows the kind of denunciations Pečat

makes.

However, the reality in which the NGO sector operates in Serbia is

rather different from the image the media (and a portion of the public)

has. A close monitoring of the resources coming in from abroad as non-re-

payable funds (grants to NGOs in Serbia) reveals that the sums are several

times smaller than the resources the state spends on the NGOs. According

to an analysis published at the end of 2011, the resources made available

93 Pečat, No 163.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-62-2048.jpg)

![68 serbia 2011 : Jud

i

c

i

ary

In response to this statement the Constitutional Court made the fol-

lowing statement to the public: ‘On the occasion of the statement of the

president of the High Judicial Council, Nata Mesarović, in which she states

that the Constitutional Court of the Republic of Serbia too is of the opin-

ion that the incomplete composition of the High Judicial Council does not

affect the legality of its work’ and that ‘it states its position thereon in the

Saveljić case when it deliberated on the objections to the incomplete first

composition of the High Judicial Council and took the view that that can-

not affect the legality of the work of the VSS because the statute provides

that the High Council makes decisions by a majority of its members [...]

for the sake of complete information the Constitutional Court of Serbia is

hereby informing the public that on 28 May 2010 it granted the appeal

of Zoran Saveljić and revoked the decision of the High Judicial Council of

25 December 2009 in so far as it terminates that judge’s office,’ the Con-

stitutional Court says. ‘In its said decision the Constitutional Court has

pronounced only on the matter of the constitution of the first composi-

tion of the High Judicial Council, whereas the Constitutional Court has not

pronounced on the legality and legitimacy of the present composition of

the High Judicial Council and will do that in its decisions in the matter of

the judges’ appeals against the decisions of the High Judicial Council,’ it

says.104

At the beginning of March 2011, the VSS Electoral Commission an-

nounced the names of the six new members of the permanent composi-

tion of this body elected by judges’ votes. The Commission said that 1,914

judges out of 2,087 had cast their votes. In other words, the new members

of the VSS won the confidence of 92% of judges.105

For its part, the Society of Judges of Serbia said that the election of

the six members had largely ‘consolidated the negative consequences of

the re-election’, which, in its opinion, puts the independence of the judici-

ary in Serbia in jeopardy. This, the Society said in a statement, was accom-

plished by excluding from the election process for VSS members as many

as 837 non-reelected judges whose status has not yet been finally decided,

104 http://www.ustavni.sud.rs18 January 2012.

105 Blic, 4 March 2011, ‘Izabrani članovi Visokog saveta sudstva’.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-70-2048.jpg)

![75

After Reforms

Ivković, and the former director of Politika newspaper publishing house

and close friend of Slobodan Milošević’s wife Mira Marković, Dragan Hadži

Antić.

Former president of the Supreme Court Zoran Ivošević says that he is

not surprised that proceedings against top members of the Milošević re-

gime are becoming time-barred because similar things have happened to

similar extent before. He says that holders of judicial office are still un-

certain about their future and therefore susceptible to influence. ‘Quite

evidently and clearly the judicial authority has not got [the promised] au-

tonomy and independence and cannot resist the pressure of the politi-

cal authority; so everything can be explained by this fact and this cause,’

Ivošević says. To recall, the SPS is in power again and one of its leaders,

Minister for Infrastructure Milutin Mrkonjić said recently that at least five

of Milošević’s associates or family members are victims of rigged trials and

that some have been convicted on trumped-up charges.

����������������

He named in par-

ticular Marko Milošević, Mira Marković, Rade Marković, Mihalj Kertes and

Dragoljub Milanović.116

The former member of the anti-Milošević movement Otpor, Momčilo

Veljković, has said he would file a petition with the court in Strasbourg be-

cause Marko Milošević was acquitted three times of charges of beating Ot-

por activists. He said he had been denied the right to a fair trial within a

reasonable time. ‘My lawyers will bring an action to the European Court

of Human Rights in Strasbourg and claim damages because, in my case,

the Serbian judiciary failed to provide and protect my right to a fair trial

within a reasonable time. I wish to point out that the Serbian state is al-

ready paying for the damage because the legal bill for the action against

Marko Milošević, which I estimate at some 15 million dinars, will have to

be paid for by the Serbian state.’117

The Požarevac Basic Court panel presided over by Vidojković acquitted

Marko Milošević for the third time, this time due to the expiry of the stat-

ute of limitations. Although it was established that on 2 May 2000 Marko

Milošević and his aides and bodyguards beat Momčilo Veljković, Nebojša

116 B92, 20 November 2011, ‘Zastarela suđenja čelnicima režima’.

117 Danas, 18 November 2011, ‘Otporaši se žale sudu u Strazburu’.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-77-2048.jpg)

![123

Crime: A Devastating Growth

regarding the obligation of schools to set up teams for protection against

violence, bullying and neglect, with as many as 70% of primary and sec-

ondary school pupils saying their school did not have such a team or they

were not aware of its existence.217

Shocking headlines such as ‘Pupil Sticks Knife in Mate’s Chest’, ‘Knifed

in School Desk’, ‘Both Chalk and Knife in Use’, ‘Pupil Fires Shots in Class-

room’ are descriptive of only the tip of the iceberg regarding violence to

which Serbian pupils are exposed. With only the most brutal of incidents

meriting coverage by the media, police records show that in the first eight

months of 2011 alone, 28 pupils were seriously and as many as 209 lightly

injured in schools. Even a case of attempted murder was registered. In

Novi Pazar, A.T. aged 14 inflicted knife wounds on a peer near their pri-

mary school. A month earlier, luckily no one was hurt when in Paraćin a

secondary school pupil fired shots in the classroom. Later in the year, a

sixth-year pupil tried to impress his mates in the same way in Valjevo. As it

turned out, the boy was only 12 years old and already had a police record.

The year before, a primary school pupil from Novi Pazar died of wounds

after being stabbed by a peer.

The Head of the Republic Education Inspectorate, Velimir Tmušić, said

that ‘violence in schools is on the rise, which, unfortunately, can be said

of society as a whole. This is why the state must address these problems in

real earnest.’ He added, ‘Not a day passes without our receiving a number

of reports. Many of the incidents are not even brought to our attention

and are dealt with at the school or local inspectorate level. The parents

are shifting the responsibility on the school, the school on the parents,

and both on the media. The combination of causes of violence is very

complex. There are more violent incidents in primary than in secondary

schools, though we’ve also received reports [of incidents] even from nurs-

ery schools.’ Fights usually break out between peers from the same class,

but also between classes and between school sports fan groups. Raids on

schools by older sports fans in order to bully pupils have also been report-

217 Vreme, 15 December 2011, ‘Sve više nasilja u školama’.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-125-2048.jpg)

![124 serbia 2011 : Jud

i

c

i

ary

ed.218

The psychologist Vladimir Nešić says that the community obviously

lacks an adequate response to the increasing violence among minors.219

The panel discussion ‘Zajedno protiv nasilja – na istoj strani’ (To-

gether against violence – on the same side) highlighted the alarming situ-

ation concerning the increase of violence among children. Significantly,

on the very first day an SOS line was introduced for victims and witnesses

of school violence, operators received reports from 16 people, who also

stressed the need for the state and society as a whole to address the prob-

lem.220

Participants in the discussion noted increasing reports of violence

and mass brawls among third-year primary school pupils. They also urged

the state and society at large to join in the fight against violence.

The prospects for the prevention and suppression of crime among

Serbia’s youngest population are best indicated by the ‘achievements’ of

the so-called ‘systemic re-education’. For instance, representatives of the

nongovernmental organization Helsinki Committee said that about two-

thirds of juvenile delinquents revert to crime after serving their sentences.

They also said that the state was not interested in solving the problem. The

Helsinki Committee’s Ivan Kuzminović warned that juvenile delinquents

resumed their criminal activities very soon after serving their sentences

and that in large cities such as Belgrade and Novi Sad 100% of delinquents

were recidivists. ‘Our overall impression after visiting several establish-

ments for juvenile delinquents is that the state is totally uninterested in

that group and has no strategy at all. On the other hand, if resocialization

has any chance of success at all, it is precisely among minors,’ he said.

Kuzminović said that for the past 10 years the Ministry of Justice had been

trying to transfer prison doctors from its jurisdiction to the jurisdiction of

the Ministry of Health. The Helsinki Committee’s Ljiljana Palibrk said that

Serbia was short of juvenile judges and that those who worked neglected

their duty to revise every six months their punishment decisions relat-

ing to juvenile delinquents. She said that ‘in 90% of cases they [juvenile

judges] do not make so much as a phone call. Also, health workers from

218 Večerenje novosti, 18 November 2011, ‘Osnovci sve nasilniji’.

219 Ibid.

220 Blic, 9 December 2011, ‘Prvog dana 16 prijava liniji SOS za nasilje u školama’.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-126-2048.jpg)

![131

Crime: A Devastating Growth

homije, charged with sexually molesting four boys, was among those who

escaped justice thanks to the inefficiency of the domestic judiciary. This

case in particular aroused the most public indignation.230

A book published by the Biljana Kovačević Vučo Fund, Zloupotrebljene

institucije: Ko je ko u Srbiji 1987.-2000. [The Abused Institutions: Who’s

Who in Serbia 1987-2000] contains the names of 1400 persons from vari-

ous spheres of society – including politics, the Academy of Sciences and

Arts (SANU), the Church, the Army, the media and the show business –

whose services Slobodan Milošević used to accomplish his political and

war aims. The book was signed by the late Kovačević-Vučo, the well-known

human rights champion and anti-war activist, and Dušan Bogdanović. On

more than 300 pages, the book lists names which are more or less well

known. Some of the persons named have been completely forgotten, oth-

ers have never been known to the public at large, and some others are still

highly influential.

Bogdanović said, ‘We’re sorry that the book contains no information

on what they have been doing since 2000 though, as you leaf through it,

you can find the names of those sitting in the government, in Parliament,

people calling the shots in the Academy of Sciences, in the media, the judi-

ciary...Such information would have made plain that there has practically

been no discontinuity in the political biographies of the most prominent

people from that era.’231

Asked to say how influential Milošević’s people

were at present, Sonja Biserko, the president of the Helsinki Committee

for Human Rights, said, ‘Let me only mention the name of Dobrica Ćosić,

who still occupies public media space. His line is crucial in defining the

narrative about the past. He still shapes public opinion.’ Milošević’s men,

she warned, are to be found in every institution of society, among the ty-

coons, all of them are there. ‘The point is not that they should all be re-

moved, but that they should really dissociate themselves from that project

and from that policy. Up till now, we’ve not seen that happen. You see, the

arrest of Mladić was accompanied with texts extolling his contribution to

the creation of Republika Srpska. After serving her Hague sentence Biljana

230 Večernje novosti, 21 November 2011, ‘Miloševićevi ljudi izbegli pravdu’.

231 Radio Slobodna Evropa, 29 June 2011, ‘Gde su danas ključni Miloševićevi ljudi’.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-133-2048.jpg)

![133

Crime: A Devastating Growth

the culprits long ago. The undeniable injustice of this is that the truth

has not been told for eight years. Even if this investigation does not bear

fruit, we will never give up, not until the culprits for Zoran’s murder are

punished.’233

Đinđić’s mother, Mila Đinđić, said that for her the current in-

vestigation was a sign that ‘...We are coming awake suddenly. Eight years

on, it’s as hard for me as it was on the first day. But what keeps me going is

the resolve to see those who gave the order brought before a court of law.

In recent days there’s been a flurry of activity regarding the investigation

into Zoran’s murder. It is high time the perpetrators were identified. All we

can hope for is that those making the promises will deliver.’234

At the middle of December 2011, Đinđić’s mother and sister lodged

a criminal complaint against the former Đinđić government members,

Nebojša Čović and Velimir Ilić, accusing them of complicity in the assas-

sination. The contents of the criminal complaint were made public on the

Peščanik (B92) website by their lawyer Srđa Popović. The two politicians

are accused of ‘failing to report the preparations for the commission of the

criminal offence of attack on constitutional order’. Čović is also accused of

‘committing, in combination with persons already finally convicted of this

offence, the criminal offence of instigation of the assassination of a repre-

sentative of the highest state bodies’. Popović further alleges that, ‘at the

beginning of February 2003, Velimir Ilić, the president of the New Serbia

party, received a letter from Milorad Ulemek, the former commander of

the Special Operations Unit, in which he was invited to join in a nation-

wide revolt modelled on October 5. In the letter, Ulemek explained to Ilić

that they would replace the present government, which he described as

submissive and condescending, with people who would take account of

the national dignity.’ ‘After learning that Ulemek was preparing an attack

on constitutional order, [Ilić] informed Nebojša Čović, the then Serbian

Deputy Prime Minister, of the contents of the letter’, Popović wrote. ‘By

knowingly failing to report this to the competent state authorities, both

have committed the criminal offence of failure to report (Article 308 of the

233 Blic, 13 March 2011, Mila Đinđić: ‘Boli me što još ne

znam ko je naredio ubistvo mog Zorana’.

234 Ibid.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-135-2048.jpg)

![134 serbia 2011 : Jud

i

c

i

ary

Criminal Code) preparations for committing the criminal offence of at-

tack on the constitutional order (Article 311 of the Criminal Code), which

is prosecuted ex officio and punishable by more than five years in prison’,

wrote Popović.235

On 18 January 2012, the Prosecutor’s Office for Organized Crime re-

ceived from Popović a supplement to the criminal complaint against Ve-

limir Ilić and Nebojša Čović on suspicion of complicity in the assassination

of Zoran Đinđić. The Prosecutor for Organized Crime, Miljko Radisavljević,

said that the supplement would be taken into consideration and stressed

that the Prosecutor’s Office was investigating the allegations made by

Popović on behalf of Đinđić’s mother and sister in the criminal complaint

lodged on 15 December 2011. In the supplement to the criminal com-

plaint, Popović analyses the public statements made by Ilić and Čović af-

ter the lodging of the criminal complaint against them. Popović argues

that the several public statements made by the two following the lodging

of the criminal complaint have merely ‘amplified the suspicions against

them, given that the statements contain an unusual amount of patent un-

truths’. In these statements, he contends, they first contradict each other

and them themselves, as well as making statements which are completely

illogical and contrary to certain factual findings by the court.236

In September 2011, Popović said that the person identified by the

member of the ‘Zemun gang’, Miloš Simović, as the orderer of the assas-

sination and referred to by the nickname ‘Ćoravi’ [one-eyed] or ‘Ćoki’ was

actually Nebojša Čović. Čović dismissed the allegation as ‘absurd’. Simović,

who had been sentenced in absentia to 30 years in prison for his part in

the assassination, made a written statement to the Prosecutor’s Office for

Organized Crime a year and a half ago, following his arrest, in which he

states that the assassination was commissioned by a man from government

nicknamed ‘Ćoravi’ and ‘Ćoki’. He allegedly gives in the statement the first

name and surname of that man. When asked to whom the nicknames re-

ferred, Popović replied that Simović had ‘made it clear that the person in

question is Čović’. Čović dismissed this grave accusation. ‘The worst thing

235 B92, 15 December 2011, ‘Čović i Ilić na sudu zbog Đinđića’.

236 Večernje novosti, 18 January 2012, ‘Radisavljević: Dopuna prijave protiv Čovića i Ilića’.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-136-2048.jpg)

![152 serbia 2011 : Jud

i

c

i

ary

pected that the ‘Ministry of Health will cooperate with the Prosecutor’s Of-

fice and the police in fighting corruption’.281

However, by the end of the year it had become evident that the pub-

lic’s expectations had been mere wishful thinking and that the announced

turnaround would not be worthy of mention. Milanović accused the ap-

propriate state authorities, particularly the Special Prosecutor’s Office, the

Security-Intelligence Agency (BIA) and the Ministry of Justice, of obstruct-

ing the fight against corruption and of dealing with the problem ‘more

theoretically than practically’.282

Speaking on the morning programme of Radio Television Serbia,

Milanović said that his fight against this widespread evil in Serbia was in

vain because he did not have the support of the prosecuting authorities

and the police. Asked why he did not request assistance from Minister of

Interior Ivica Dačić, Milanović replied, ‘What’s the use of asking him for

anything – he has no clout in the police at all? Why, I have more clout

there than he has!’283

Milanović identified as the main problem in the fight against corrup-

tion an influential ‘political structure’. When asked by the host to name

that structure, he replied, ‘Why, the office of President (of Serbia Boris)

Tadić – that’s the fundamental problem in our society and no one dare say

this in public’.284

Milanović also recalled the scandal involving the purchase

of vaccines against the new swine influenza (A-H1N1), suggesting that the

ongoing criminal proceedings were selective. He said that ‘it’s an open

secret that the [original] criminal complaint encompassed more persons

[then actually charged]! Prosecutor (Miljko) Radisavljević sent the crimi-

nal complaint back so that it may be corrected and eight names left out...

Only three of the names remained. How come the complaint does not in-

clude the name of the then minister [of health] Tomica Milosavljević?!’285

281 Tanjug, TV B 92, 10 June 2011.

282 Blic, 14 December 2011, ‘Savetnik ministra na RTS optužio BIA i tužioce’;

RTS, 13 December 2011. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f4fxTQAJgDA.

283 Ibid.

284 RTS, 13 December 2011 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f4fxTQAJgDA.

285 Ibid.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-154-2048.jpg)

![160 serbia 2011 : Jud

i

c

i

ary

istries, in the provincial government in Vojvodina, 13 municipalities, 19

public enterprises and five government institutions.

The programme director of Transparency Serbia, Nemanja Nenadić,

said the report of the State Audit Institution highlighted a big problem in

public enterprises. In his opinion, the ‘problems concerning public en-

terprises, regardless of whether they are subsidized or operate at a profit,

are due to insufficient control and strong political influence on their

operation’.306

Media corruption

In September, the Anti-Corruption Council published a Report on

Pressures on and Control of Media in Serbia. Owing to the highly criti-

cal nature of the Report, the majority of the media outlets, particularly

print media, did not publish even the most elementary information con-

tained in the report. The Council says it has ‘[...] gathered data on the ba-

sis of which it can be concluded that the media in Serbia are exposed to

strong political pressure and, therefore, a full control has been established

over them’.307

It stresses that ‘There is no longer a medium from which the

public can get complete and objective information because, under strong

pressure from political circles, the media pass over certain events in si-

lence or report on them selectively and partially’.308

The Report names the media in question and exposes their finan-

cial-business connections with the public sector and the authorities. The

Council’s analysis encompasses all the government ministries, certain re-

public public enterprises and certain City public utility companies, as well

as agencies and other state bodies.

On the basis of extensive documentation the Anti-Corruption Coun-

cil points to three major problems in the media sector: lack of transpar-

ency in media ownership; economic influence the state institutions exert

306 Ibid.

307 ‘Izveštaj o pritiscima i kontroli medija u Srbiji’, Anti-Corruption

Council of the Serbian Government, 19 September 2011.

308 Ibid.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-162-2048.jpg)

![192 serbia 2011 :

A

pparatus of

P

ower

On 4 March 2011, the Odbrana [Defence] media centre presented the

so-called Defence White Paper of the Republic of Serbia.362

The state sec-

retary at the Ministry of Defence, Dr Zoran Jeftić, introduced the book as

a document which ‘acquaints, in a transparent way, the widest domestic

and world audiences with the processes, accomplishments, as well as the

projection of development, of the system of defence of our country’. He

stressed that the ‘vision of our development is based on a vision of an

advanced and modern Serbia as a member of the European Union, inte-

grated in collective security systems, with an army which with its strength

can guarantee peace and stability in the region [...]’363

Professionalization undermined by

conservatives and traditionalists

The postponement of the granting of EU to Serbia candidate status

found a correspondent resonance in the Army and Ministry of Defence

structures. Both the Army and the Ministry of Defence had geared all their

reform efforts and achievements to the furtherance of Serbia’s pro-Euro-

pean policy. For instance, Šutanovac had said before 9 December: ‘I am

also pleased because the European Commission in its opinion stressed

that the Serbian defence system already meets all European standards and

that we are making continuous progress in reforms’.364

President Tadić re-

proached certain EU members for being ‘unfavourably disposed towards

us’ and asked Europe: ‘Today we can look the European Union straight in

the face and say that we have done what needed doing. Can the European

Union do the same?’365

Whatever faults one may find, one should not overlook the achieve-

ments of the Army and the Ministry of Defence: they were at the forefront

of the reforms, with the professionalization of the Army the biggest suc-

362 ‘Vizija sistema odbrane’, Odbrana magazine, No. 132, 15 March 2011.

363 Ibid.

364

13 ‘Dobar dan za evropsku Srbiju’, Danas, 13 October 2011.

365 ‘Ugrožena profesionalizacija’, Helsinška povelja, double

issue157-158, November-December 2011.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-194-2048.jpg)

![193

The Army: Professionalization

cess in reforming the defence system. Paradoxically, it was precisely the

military – by its nature one of the most conservative segments of society –

which deserved to be called the ‘locomotive of progress’ in Serbia.

Praise for the reform successes in the defence system was also received

from abroad. Thus, the Minister Šutanovac said the following in a report:

‘We have received confirmation that the Ministry of Defence has done an

excellent job regarding reforms from international institutions such as the

EU, UN and OSCE [...].’366

Istvan Gyarmati, director of the International Cen-

tre for Democratic Transition in Budapest and advisor at the NATO Defence

College, made a very positive assessment of the achievements of Serbia’s

military reforms: ‘The Army of Serbia has been reformed so as to be ab-

solutely compatible with the standards of NATO. More correctly, reforms

in the Serbian Army have in many aspects been more successful than re-

forms in some members of the Alliance.’367

Importantly, Jane’s Defence

Weekly published in its September 2011 issue an article by its Europe edi-

tor, Gerard Cowan, which represents a highly positive analysis of the ad-

vancement and modernization of Serbia’s armed forces.368

The postponement of the granting of EU candidate status was seized

upon by the conservative bloc to pick holes in the professionalization of

the Army, saying that the Army had been ruined and that ‘Serbia is los-

ing its autonomy’. The professionalization was especially strongly opposed

by retired generals and other retired officers. For instance, retired colo-

nel Milan Jovanović said, ‘Šutanovac’s reform and professionalization of

the Army has wrapped up the sale of Serb independence. In such circum-

stances, our Government will only be (and probably already is) is the serv-

ice of the interests of the Western powers.’369

At the end of October, the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) published a

white paper (something like a party programme) in which they promise, if

they come to power at the next parliamentary elections, to de-profession-

366 D. Šutanovac, signed text: ‘Reforma sistema odbrane –

evropeizacija Srbije’, Danas, weekend issue 21-22 May 2011.

367 ‘Reforma Vojske Srbije primer i za članice NATO’, Danas, 4 March 2011.

368 ‘Vojska Srbije grabi ka standardima NATO’, Danas, 9 September 2011.

369 Milan Jovanović: ‘Šutanovčevo šutiranje odbrane’, Tabloid, 26 May 2011.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-195-2048.jpg)

![196 serbia 2011 :

A

pparatus of

P

ower

‘great pleasure over sending for the first time in the history of our country,

and in cooperation with our French partners, two naval officers on a piracy

fighting mission [...] although today is a trying day of talks about security

in our southern province [...]’.377

The military industry: no repetition

of the 2010 successes

The Serbian military industry’s sales of hardware in world markets

in recent years, and in 2010 in particular, were respectable. At the begin-

ning of 2011, in an interview with Politika, Minister Šutanovac set out not

only immediate plans for the production and sale of products abroad in

the current year but also the industry’s strategic development lines.378

He

pointed out that the military industry’s exports during his term had been

significant: ‘In 2007, exports of armaments and military equipment were

worth USD75 million; in 2008, they were worth USD183 million; in 2009,

the figure was USD246 million; and in 2010 it was USD247 million. This

means that USD 750 million worth of exports of armaments and military

equipment has been realized during my term as Minister of Defence.’379

At the beginning of 2001, the British weekly The Economist published

a story, based on the figures set out by Šutanovac, reporting a ‘boom’ of

the Serbian military industry.380

The weekly writes that the Serbian mil-

itary industry was becoming ‘increasingly sophisticated’, among other

things. However, the military analyst, Aleksandar Radić, and the promi-

nent economic expert, Dr Vladimir Gligorov, did not share that view. They

believe that ‘in the field of defence industry too Serbia must overcome

its technological backwardness and to orient itself towards research and

development if it wants success in the long term’.381

In 2010, the military

industry concluded contracts with foreign customers worth some USD1.2

377 Ibid.

378 ‘Svi hvale našu “Lastu”’, Politika, 23 January 2011.

379 Ibid.

380 ‘Novi srpski “bum”’, Danas, 11 January 2011.

381 Ibid.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-198-2048.jpg)

![197

The Army: Professionalization

billion.382

Given the unfavourable circumstances in the country and the

world, the realization of the purchase orders is highly uncertain.

Considering that no data on the military industry’s export perform-

ance for 2011 have been made public, one can assume that exports were

modest. The large social upheavals during 2011 in traditional markets

(such as Libya and Algeria) have considerably upset the industry’s con-

tracts as well as strategic plans. In spite of this, Minister Šutanovac said

he would be visiting the countries in question despite the changes at the

top.383

No follow-up to the announcement has come to public notice.

Unchanged attitudes to NATO and military neutrality

The Strategic Military Conference for partners in Belgrade in mid-

June triggered a new anti-NATO campaign. Although the conference hosts,

particularly the Ministry of Defence, insisted that the international gath-

ering was not a NATO summit, they were not believed. The secretary of state

at the Ministry of Defence, Tanja Miščević, in particular sought to dispel

any doubts in this regard: ‘The important thing is to be specific. This is not

a NATO summit. Those who are saying [this is] a NATO summit are betray-

ing their ignorance of the matter. The NATO summit is the highest political

gathering of the organization, which brings together the member states

of the North Atlantic Alliance and is always organized in a member state.

Serbia cannot be the organizer of a NATO summit because it is not a mem-

ber of that alliance.’384

The leader of the Democratic Party of Serbia (DSS), Dr Vojislav

Koštunica, was among those who raised their voices against the holding

of the meeting. ‘Following months-long refusals from parties which are

close to it regarding certain important political positions, the Democratic

Party of Serbia has decided to organize a protest against the holding of the

NATO conference in Belgrade on its own and to urge the citizens to take to

the streets and thus express their attitude to a subject which provokes the

382 Ibid.

383 ‘Hoću da idemo u Tripoli’, Danas, 27 September 2011.

384 ‘Ovo nije samit NATO’, Danas, vikend issue, 11 – 12 June 2011.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-199-2048.jpg)

![198 serbia 2011 :

A

pparatus of

P

ower

most ill feeling among the public,’ he said.385

The DSS vice-president, Dr

Slobodan Samardžić, said that the party had been prompted to act ‘by the

fact that NATO is a current and burning topic in Serbia. Not because [this

fact] is visible, but because it is not visible. And it is not visible because the

Serbian authorities are relentlessly pushing Serbia into NATO while on the

other hand they are trying to make sure this matter is not talked about.’386

The DSS leaders and people of like minds insist that Serbia ‘has had it up

to here of cooperation’ as far as its participation in the realization of the

North Atlantic Alliance Partnership for Peace programme is concerned.

Judging by various opinion polls and the writings of anti-European

outlets such as the weekly Pečat and the portal of Nova srpska politička

misao (New Serbian Political Thought), one could come to the conclusion

that most members of the public were as highly critical of NATO in 2011

as they were the year before.387

While most respondents opposed Serbia’s

rapprochement with NATO, they could not put forward any valid arguments

in response to the question: Why not NATO? Traditional anti-European at-

titudes, a poison constantly shoved down their throats, and the mantra

‘They bombed us’ were the best they could come up with.

The same also goes for Serbia’s military neutrality, although this neu-

trality is a very questionable, unfounded and problematic notion from

whatever angle it is viewed. Not even the minister of defence had enough

courage to confront and expose the manipulations of the quasi-patriots.

On the eve of the Strategic Military Conference, Minister Šutanovac all but

sought to justify himself in response to the ill-intentioned and thinly-dis-

guised arguments that Serbia was about to renounce its military neutral-

ity: he said that the Conference ‘does not signify Serbia’s abandonment of

its proclaimed military neutrality’.388

385 ‘NATO izvodi DSS na ulicu’, Politika, 10 June 2011.

386 Ibid.

387 ‘Ko je lomio čiji Beograd?’, Nova srpska politička misao, 25 June 2011;

‘Milomir Stepić: Nema razlike između EU i NATO-a (I deo)’, interview with Dr

Milomirom Stepićem, ‘geographer and geopolitics expert’, Pečat, 1 March 2012.

388 ‘Šutanovac: Ne odustajemo od vojne neutralnosti’, Politika, 10 June 2011.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-200-2048.jpg)

![199

The Army: Professionalization

Many NATO representatives in Brussels argue that Serbia’s military

neutrality will be difficult to sustain in the future. One of their arguments

is the increasing emergence of global problems which call for global solu-

tions.389

The Centre for Euro-Atlantic Studies in Belgrade pointed out that

‘Serbia has four agreements with NATO alone, is establishing military co-

operation with the United States, has foreign troops on its territory and

has no sovereignty over 15% of its territory. Considering its capacity and

budget, it cannot afford to be neutral [...].’390

The arrest of Ratko Mladić

Based all that was published and broadcast by the media following

the arrest of Ratko Mladić on 25 May 2011, one may conclude that a very

wide network of both institutions and individuals had been helping to

hide him. Nevertheless, the authorities maintained that the secret serv-

ices, Army and police had had no part whatever in that.

Earlier in the year, it had been argued in public increasingly openly

that Mladić’s hiding had become an unbearable financial and political

burden for the state. The prevailing opinion was that his arrest would be

argument enough for securing candidacy for EU membership. This was

largely confirmed by the ‘show’ that took place early on the morning of

25 May in the Vojvodina village of Lazarevo, as well as by the fact that the

authorities and numerous media outlets strove to outdo each other in

portraying it as a triumphal operation. The members of the Security In-

telligence Agency (BIA) who carried out the arrest were praised in partic-

ular for both the success of the raid and for their integrity and modesty,

because ‘they did not ask for the (promised) reward for locating the gen-

eral’ and because they ‘looked upon [the operation] as part of their regu-

lar duties’.391

389 ‘Vojna neutralnost Srbije teško održiva’, Danas, 16 December 2011.

390 ‘Vojna neutralnost Srbije?’, Danas, 3 November 2011.

391 ‘Moralni čin ili kalkulantska predstava’, Helsinška

povelja, double issue 151-152, May-June 2011.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-201-2048.jpg)

![200 serbia 2011 :

A

pparatus of

P

ower

Interestingly, no one from the Ministry of Defence and the General

Staff made a statement on the occasion of the arrest. On the eve of the ‘ar-

rest’, the then chief of the General Staff, Miloje Miletić, was asked by Poli-

tika daily if he had any message for Ratko Mladić. He replied: ‘I don’t see

cooperation with the Hague [tribunal] as a stumbling block but as an issue

which will show that Serbia shares the same values with Europe. The Army

of Serbia as an institution does not concern itself with evaluation of co-

operation with the Hague tribunal. The Republic of Serbia has made clear

its position that all who have committed war crimes ought to be called to

account and that they cannot hide behind alleged general social interests.

I consider that everyone ought to take responsibility for their acts and de-

cisions and, if necessary, to appear before the tribunal, which is the only

competent venue for establishing responsibility in cases like this. In so

doing they will free the society and citizens of Serbia from a great obsta-

cle on the path to further progress. Any avoidance of personal responsibil-

ity is incompatible with the ethics of our calling and runs counter to our

Code of Honour. Our officer is graced with soldierly virtues, with honour

and chivalry.’392

The former chief of the Army’s Security Service, General Aleksandar

Dimitrijević, said that ‘Ratko Mladić was too late for any of the solutions

that had been at his disposal. If he thought he was innocent, then it made

no sense for him to hide for so many years... If he thought he was guilty,

he again had two options: first, to surrender voluntarily and bear respon-

sibility for what he did or did not do (true, there are many things that

Mladic did not do, but he did nothing to prevent the murders and punish

those responsible for them) and, second, to fulfil the promise he allegedly

made at some time or other that he would not give himself up alive to the

tribunal in The Hague.’ Asked ‘why suicide would have been an option’,

Dimitrijević replied: ‘I think that by so doing Mladić would have removed

Serbia from the black list and helped it so it would not become the topic

number one in the world again.’393

392 ‘Pravi oficiri ne beže od suda’, Politika, 3 May 2011.

393 ‘Mladić je morao da izvrši samoubistvo’, E-novine, 23 June 2011, an interview from

BH Dani magazine published with the permission of the author and the editorial staff.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-202-2048.jpg)

![201

The Army: Professionalization

Some journalists and military affairs experts were dismayed at Mladić’s

‘poor condition and the beggars’ clothes’ that he wore when the police

took him out of his hiding place to display him to the public in front of

TV cameras. For instance, the Politika journalist, Miroslav Lazanski, said

in the TV B92 programme ‘Utisak nedelje’ that he had been greatly ‘dis-

appointed’ at the ‘general’s undignified appearance [...] at the time of his

arrest. He who fought in war for the Serbs in Bosnia, and also outside Bos-

nia, a byword for military greatness [...] ought not to have let them him ar-

rest him in that state, in a cloth cap and a jacket of some sort [...].’394

Serbia received tribute for Mladić’s arrest from the international com-

munity. President Boris Tadić joined in the jubilations and called on oth-

ers in the neighbourhood to arrest ‘their own criminals’, that is, those who

had committed crimes against the Serb people!

In a signed text, the director of the Humanitarian Law Centre, Nataša

Kandić, described the obsequious attitude towards Ratko Mladić as fol-

lows: ‘I am not yet sure that Serbia has disowned Mladić and the other

generals responsible for the genocide in Bosnia. The sympathies the rep-

resentatives of the state and the media expressed for Mladić are yet an-

other disgrace of ours. The deputy prosecutor offered him strawberries. His

wishes to be visited by the minister of health and the parliament speaker,

as well as to be allowed to pay a visit to his daughter’s grave, were granted.

The whole of Serbia was informed about his diet while in detention, as

well as that he left for The Hague in the suit he had worn at his son’s wed-

ding. He was given the treatment of a star.’395

President Tadić categorically

denied the speculations concerning Mladić’s period in hiding and that his

arrest had been timed to precede the decision about Serbia’s European

future. He said that since the forming of the Government and of the new

Council for National Security, which integrates the work of all the agen-

cies, ‘all the appropriate authorities’ had been ‘working flat out’ to locate

and arrest him. At this moment, he said, ‘an investigation is in progress

394 ‘Moralni čin ili kalkulantska predstava’, Helsinška

povelja, double issue 151-152, May-June 2011.

395 Nataša Kandić: ‘Sramotno ispoljavanje simpatija prema generalu

Ratku Mladiću’, Danas, weekend issue, 2-3 July 2011.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-203-2048.jpg)

![202 serbia 2011 :

A

pparatus of

P

ower

into all the circumstances surrounding Mladić’s hiding and whether any-

one was involved in his protection against the law’.396

By the end of February 2012, the public had received no information

whatever about who had helped Mladić, when and how.

Barricades in the north of Kosovo

After units of the Kosovo Special Police (ROSU) ‘occupied’ the Brnjak

administrative crossing on 24-25 July 2011 in order to ‘establish full con-

trol also over the border crossing of their state’, local Serbs ‘prevented

the Kosovo special forces from taking over the nearby Jarinje crossing as

well’, Belgrade media reported.397

The action of the Kosovo police provoked

fierce reactions not only in the north of the ‘southern Serbian province’

but also in Serbia. Hardly anybody foresaw that that would be a prelude

to armed skirmishes between KFOR and the ‘Serb people from the north of

Kosmet’ which nearly escalated into a wider conflict.

Serbian media detected in the move of the Pristina government an

intention to condition Serbia’s EU candidate status. Slobodan Petrović,

leader of the Serbian Autonomous Liberal Party, deputy prime minister

and minister for local self-government in the Kosovo government, in a

way confirmed this: ‘This is a real dilemma: one could indeed interpret

this as choosing the time of Serbia’s candidacy [decision] to address the

unsolved problems holding back the economic development of Kosovo.

The citizens in the north of Kosovo regard the action of the Pristina gov-

ernment as an attack on them, but this isn’t the case at all [...].’398

396 ‘Tadić: “Istražićemo ko je sve pomagao Mladiću”’, Danas, 1 June 2011.

397 ‘Kosovski specijalci zauzeli prelaz Brnjak na severu Kosova’, Blic, 25 July 2011.

398 ‘Na severu kriminalci jači od svih institucija’, interview

with Slobodan Petrović, Danas, 30 August 2011.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-204-2048.jpg)

![206 serbia 2011 :

A

pparatus of

P

ower

Metohija and in the Ground Security Zone in the light of the recent events

[...]’ at the administrative crossings.412

Nevertheless, Politika’s military-political commentator-analyst-expert

Miroslav Lazanski interpreted the meeting as little short of an ultimatory

warning to the KFOR representative to the effect that Serbia and its Army

would no longer permit any violence against civilians in the north of Kos-

ovo: ‘[...] this is why the deputy chief of the General Staff of our Army ur-

gently summoned the KFOR deputy commander to Niš and warned him

there that the Army of Serbia was not going to stand with its arms crossed

and watch any new violence against Serbs in the north of the southern

Serbian province. Nice one, General Bjelica, that’s the way to do it!’413

A month later, Lazanski mused: ‘Specifically, what can Serbia do if

there is a displacement of Serbs in the north of Kosovo, if there is an open

attack by KFOR or Pristina forces on the local population? We can, for the

nth time, repeat the appeal for the cooling of passions [...]’414

‘We also can,

on our side of the administrative line, put up a tent settlement with warm

blankets and beans cooked in army field kitchens for all who might have

to flee from the north of Kosovo. But what if the Serbs from the north

of Kosovo do not run but stay there and engage in some sort of danger-

ous semi-guerrilla war? Our beans will get cold. Is there any of this in the

plans mentioned by General Miletić [...].’415

Minister of the Interior Ivica Dačić made a number of statements in

a similar vein: ‘The red line for Belgrade would be an armed attack on

the Serbs in Kosovo and Metohija. [Kosovo prime minister Hashim] Thaqi

must know that an attack on the Serbs in Kosovo would also be an attack on

Belgrade. Serbia cannot and will not watch something like that calmly.’416

Some 10 days before the incidents at Jarinje, Patriarch Irinej addressed the

412 Ministry of Defence website (www.mod.gov.rs): ‘Susret generala

Bjelice i zamenika komandanta KFOR-a’, 28 July 2011.

413 Miroslav Lazanski, regular column, Politika, 30 July 2011.

414 Miroslav Lazanski: ‘Plan za Kosovo’, Politika, 30 July 2011.

415 Ibid.

416 ‘U boj za Kosovo’, E-novine, 24 November 2011, the

minister’s statement quoted from Press.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-208-2048.jpg)

![208 serbia 2011 :

A

pparatus of

P

ower

Although the subject of democratic and civilian control is a very popu-

lar one, there is no information that such control really exists in practice.

Research by the Belgrade Centre for Security Policy on how safe people

feel is very indicative.419

The Centre’s director, Sonja Stanojević, said that

people in Serbia ‘feel at their safest in their homes (84.5%)’ and then in

the town or village in which they live (77.9%). ‘[...] and, lastly, two-thirds

of male and female citizens of Serbia (75.3%) feel physically safe’, a con-

siderably higher percentage than in some large European cities, she said.

Stanojević found it ‘concerning that the citizens do not recognize in the

state institutions a factor which affects their personal safety’, saying that

‘only 6.1% of respondents believe they are safe because the institutions

are doing their job property [...] This tendency to distrust the institutions

was confirmed when the respondents were asked who they could trust for

their protection. Two-thirds of citizens would trust themselves (50.3%),

friends (8.4%) and neighbours (7.6%) [...]’ and a very small number would

trust the institutions. Stanojević attributed such ‘citizens’ perceptions’ to

the ‘legacy of the 1990s, when the citizens were let down by the institu-

tions. The institutions enjoy much more confidence among the respond-

ents concerning their readiness to protect the security of the state [...] This

shows that the key institutions concerned with personal safety, such as

the police and the judiciary, have not been sufficiently reformed, nor have

they brought their services closer to the citizens [...].’420

The VO and VBA military agencies marked their anniversaries in 2011.

On VOA Day, 6 May, a permanent exhibition on the history of the military

intelligence service in Serbia was opened in the VOA building,421

and Colo-

nel Danko Štrbac, one of the service’s chiefs, gave an extensive interview

to the daily Danas.’[...] in the aftermath of the war in BiH [Bosnia and

Herzegovina] and the arrival of large numbers of “Islamic fighters”, that is,

mujahedin, the Balkans has gained in importance as a long-term and sta-

419 Sonja Stanojević, director of the Belgrade Centre for Security Policy, on 21 May 2011

presented the results of a public opinion poll conducted in Serbia by the Centre; the topic

was ‘How safe do the citizens of Serbia feel’; the Centre’s website: www.ccmr-bg.org.

420 Ibid.

421 ‘Tajne velikih majstora’, Odbrana magazine, No. 137, 1 June 2011.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-210-2048.jpg)

![209

The Army: Professionalization

ble logistic, recruitment and financial foothold for terrorists on Europe’s

soil [...] In the territory of Serbia, however, they operate as a regular mili-

tary formation, the Kosovo Security Force (KSF). With support from certain

states of the West, their equipment and training continue in order that

they may achieve full operational capacity by 2012. The advent of the KSF

has attracted attention, from the very idea of their formation until today.

These forces are in the sphere of [our] interest as a phenomenon which

jeopardizes the sovereignty of Serbia and the security balance in the re-

gion [...] The situation in KiM [Kosovo and Metohija] remains the biggest

generator of regional challenges, risks and threats, and is characterized by

continuing ethnic divisions and tensions, as well as a high degree of cor-

ruption and crime.’422

Such allegations square with the stereotypes of the numerous ‘Islam-

ologists’ in Serbia. The above statement shows that Kosovo and Sandžak

are regarded as priorities as far as security risks are concerned.

The VOA director, Dragan Vladisavljević, said in an interview with

Večernje novosti that the biggest potential risks come from Kosovo because

‘[...] parties and movements which are exclusive, oppose dialogue between

Belgrade and Pristina or strive for the territorial unification of all Albani-

ans in the region are gaining in strength on the political scene in the Prov-

ince’. ‘Such tendencies,’ he said, ‘can result in new incidents.’423

Besides Kosovo, Vladisavljević identified other threats such as: the dif-

ficult and slow transition of the states in the region, their exposure to sanc-

tions and economic crisis, and the fact that the region is a crossroads of

trafficking of various kinds, organized crime, proliferation of armaments

and military equipment and of dangerous substances, migrations and in-

ternational terrorism. Vladisavljević stressed the connections between ‘lo-

cal’ extremists and international terrorist networks.424

The Land Forces (KoV) and the VBA marked their anniversaries on the

same day, 12 November. In 2009, the VBA celebrated the 170th anniver-

sary of the establishment of the counter-intelligence service in Serbia.

422 ‘Religijski ekstremisti koriste švercerske kanale’, Danas, 5 May 2011.

423 Večernje novosti, ‘Priština preti celom regionu’, 6 March 2012.

424 Ibid.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-211-2048.jpg)

![210 serbia 2011 :

A

pparatus of

P

ower

Few other countries can boast of such a long tradition. The anniversary

ceremony was attended by military envoys in Belgrade, high dignitaries of

all the religious communities headed by Patriarch Irinej and many repre-

sentatives of Serbia’s cultural and public life. The composition of the audi-

ences that attended both the 2010 and 2011 ceremonies was the same.425

President Tadić delivered an address and said, among other things: ‘In

security terms, we are today a safe country. There is no dilemma whatever

that our international credibility is enhanced, and that the overall cred-

ibility of Serbia and the Serb people is at a higher level than it was be-

fore [...]. ‘Each of our citizens ought to know that the security factor – that

our Army, that our police, our security forces [...] contribute by their work

not only to the safety of the citizens but to the overall economic and tech-

nological development of our country and, ultimately, to the enhance-

ment of the overall credibility of the Serb people and the Serbian state,’

he added.426

The medals

Another tradition of the Serbian army – the award of military com-

memorative medals and certificates – was revived. The first 416 awards

were made to military and civilian members of the Ministry of Defence

and the Army of Serbia on Statehood Day and Army of Serbia Day, 15 Feb-

ruary 2011. Colonel Slađan Ristić, head of the Department for Tradition,

Standards and Veterans, announced that military commemorative medals

would be presented to another group of persons for their participation in

combat on the territories of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

(SFRY), Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY) and Republic of Serbia.427

‘In

order to be awarded a decoration for participation in combat operations

on the territories of the SFRY and the FRY, a person must produce evidence

425 ‘Sigurnost je uslov razvoja’, Odbrana magazine, No. 149, 1 December 2011; Ministry

of Defence website, 12 November 2011; ‘Obeležen Dan Vojnobezbednosne agencije’,

Danas, weekend issue, 12-13 November 2011; Tanjug i Beta reports, 12 November 2011.

426 Ibid.

427 ‘Medalje za učešće u ratovima na prostorima bivše Jugoslavije’, Politika, 3 April 2011.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-212-2048.jpg)

![211

The Army: Professionalization

that he or she was there and did nothing contrary to the provisions of in-

ternational humanitarian law and the laws of war,’ he said.428

In response to public reaction to the award of military commemorative

medals, State Secretary Igor Jovičić said, ‘There is no cause for malicious

interpretations regarding the commemorative medals!’429

’The military

commemorative medals are awarded on the basis of facts concerning a

soldier’s career such as participation in peace operations, length of army

service, anniversaries and also taking part and being wounded in combat

operations,’ he said. ‘Medals are awarded in all armies on the basis of the

same and similar criteria, so there is no reason whatever why such medals

should not be awarded to members of our Army. Military commemorative

medals are awarded to members of the Army of Serbia who have hon-

ourably and professionally carried out their duty, and if they have also

taken part in combat operations, it is understood that throughout their

military calling they acted in a manner which distinguishes them from

all those who have been sentenced by the International War [Crimes] Tri-

bunal in The Hague. In considering the matter of commemorative medals

one ought not to confuse the issues regarding the character of combat op-

erations on the territory of the former SFRY and the question of the legacy

and heritage of the former JNA [Yugoslav People’s Army],’ he said.430

Conspicuously, in their statements Ristić and Jovičić did not use the

word ‘war’: their phrasing ‘medals for participation or being wounded in

combat operations on the territory of the former Yugoslavia’ corresponds

with the thesis that Serbia took no part in the war. The announcement

that ‘medals for gallantry, honour and honesty’ would be awarded drew

a highly negative reaction in neighbouring countries. The European Par-

liament’s rapporteur for Serbia also reacted. The whole matter then disap-

peared from public view.

428 http://dnevnik.hr/vijesti/svijet/srbija-odlucila-odlikovati-

vojnike-koji-su-ratovali-u-hrvatskoj-i-bih.html.

429 ‘Jovičić: Nema mesta zlonamernom tumačenju oko

spomen-medalja’, Danas, 6 April 2011.

430 http://www.mod.gov.rs/novi_lat.php?action=fullnewsshowcomments=1id=3421.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-213-2048.jpg)

![232 serbia 2011 :

A

pparatus of

P

ower

and democratic control over them. In its Analytical Report453

accompany-

ing its recommendation to the European Council regarding Serbia’s ap-

plication for membership of the EU, the Commission states: ‘Unlike most

EU intelligence agencies, the Serbian security agencies have investigative

powers. This raises serious concerns, as they are in the position of con-

trolling intelligence material used in criminal investigations. Overall, an

extensive constitutional and legal framework for the democratic civilian

supervision of security forces is in place. Further efforts are needed in

order to strengthen parliamentary capacity and expertise. The ability of

security agencies to carry out special investigative measures in criminal

investigations gives rise to serious concerns.’

In its resolution of 29 March 2012 on the European integration proc-

ess of Serbia, the European Parliament says:

‘[...] Calls on the authorities to continue their efforts to eliminate the

legacy of the former Communist secret services, as a step in the democra-

tisation of Serbia; [...]’.

In the resolution, the European Parliament recalls the importance of

further security sector reforms, increasing parliamentary supervision and

control of the security services, as well as of opening up the National Ar-

chives, and in particular the documents of the former intelligence agency,

the UDBA, as well as encouraging the authorities to facilitate access to those

archives that concern former republics of Yugoslavia and to return them

to the respective governments if they so request.454

453 http://www.seio.gov.rs/upload/documents/eu_dokumenta/

misljenje_kandidatura/izvestaj_o_napretku_2011.pdf

454 http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/seance_pleniere/textes_adoptes/

provisoire/2012/03-29/0114/P7_TA-PROV(2012)0114_EN.pdf](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-234-2048.jpg)

![264 serbia 2011 : Independent

R

egulatory

A

genc

i

es

other interest groups in order to influence the independence of this insti-

tution and undermine its work through denunciation. This attitude, born

of political immaturity, is undermining the all the efforts towards social

progress.

The Anti-Corruption Agency has the following competences: keeping a

register of officials’ property and gifts given to them; oversight of officials’

property cards; oversight of the funding of political campaigns and keep-

ing records of financial reports of political parties; dealing with conflicts of

interest; introduction and monitoring of the implementation of integrity

plans in organizations and institutions of public power; monitoring the

implementation of the National Strategy and Action Plan for implement-

ing the National Strategy for the Fight against Corruption. The Agency

may also conduct research, draw up and implement training programs,

launch campaigns for raising anti-corruption awareness, cooperate with

civil society organizations and other professional and scientific organiza-

tions, analyze legislation and initiate its harmonization and amendment,

cooperate with other domestic and foreign organizations and institutions.

The Agency plays a preventive role and may carry out supervision and

initiate misdemeanor and criminal complaints in connection with viola-

tions of the Law on the Anti-Corruption Agency.494

The public continues to

demand that the Agency should be given wider powers. The Agency is per-

ceived as a smokescreen for the authorities’ political will to fight corrup-

tion, with pressure being brought to bear on the Agency rather than on

the institutions having the powers to investigate and make arrests. Mem-

ber of the Agency’s Board Professor Čedomir Čupić, said he would demand

an extension of the Agency’s competences to ‘prosecutorial and execu-

tive’. He explained, “The Agency will not produce results with its [present]

competences.”495

494 http://www.acas.rs/sr_cir/zakoni-i-drugi-propisi/zakoni/zakon-o-agenciji.

html. The Law began to be implemented on 1 January 2010.

495 http://www.smedia.rs/vesti/vest/76772/Cedomir-Cupic-Agencija-za-borbu-protiv-

korupcije-Korupcija-Cupic-Agencija-da-dobije-istraznu-i-izvrsnu-funkciju.html#.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-266-2048.jpg)

![281

Integration into the Political Community

gives it wide decision-making powers in accordance with the law. However,

the provisions of Article 10 are not fully implemented in respect of all na-

tional councils alike. In the European Parliament’s 19 January 2011 reso-

lution on the European Integration Process of Serbia (B7-0021/2011), the

European Union sends the following clear signal in paragraph 24.: ‘[The

Council of Europe] Welcomes the efforts made by Serbia in the field of the

protection of minorities; underlines, however, that access to information

and education in minority languages remains to be improved, in particu-

lar in the case of the Bosniak, Bulgarian, Bunjevci and Romanian minori-

ties;’. It should be noted that in the field of education the National Council

of the Bunjevac national minority contributes towards the costs of teachers

since their elective subject, it says, is ‘not included in the teacher financing

drop-down menu’ of the Ministry of Education and Science. In the field

of information, the Bunjevac national community has no editorial staff in

provincial and local media outlets and must contribute towards the cost of

‘production and broadcasting’, with the media space provided by RT Vojvo-

dina and Radio Novi Sad.

Other national councils have similar or identical views regarding the

partial implementation of Article 10 of the Law on National Councils of

National Minorities, saying that national councils do not play an active

role in proposing and initiating specific regulations (the National Council

of Bosniaks). The National Council of Greeks says that the non-implemen-

tation of this Article of the Law is mostly due to the bad financial situation,

or more specifically, that the state does not earmark enough funds from

its budget to professionally implement and enforce the statutory rights.

The National Council of Macedonians considers that implementation of

the Law is much better at the republic and provincial than at local level.

The National Council of Vlachs considers that Article 10 is imple-

mented fully as regards the functioning of national councils. As regards

the members of national minorities on the grounds of a previously granted written

power-of-attorney; 14) Take positions, make initiatives and undertake measures in

respect of all the issues directly related to the status, identity and rights of a national

minority; 15) Decide on other issues entrusted to it pursuant to the law, by the

documents of the autonomous province or by the unit of local self-government.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-283-2048.jpg)

![292 serbia 2011 :

Mi

nor

i

t

i

es

matters of public information in the Slovak language. The Committee

seeks to facilitate access to information in the Slovak language as well as

to develop and promote local and provincial media’s resources for provid-

ing information in the Slovak language. The National Council is the holder

of the founding rights over the weekly Hlas ljudu, which has been in cir-

culation since 1944. The Information Committee proposes measures in the

field of public information regarding technical matters, promotion and

training of personnel, questions of style and presentation, use of profes-

sional terminology in accordance with the new legal provisions, linguis-

tic trends and the Slovak literary language and other questions of public

information regulated by law and the National Council’s Statute aimed at

protecting the rights of and providing information in the mother tongue

to members of the Slovak national minority. The National Council does

not concern itself with the editorial policy of any media outlet providing

information in the Slovak language.

The National Council of the Macedonian national minority is the

founder of the newspaper-publishing institution Macedonian Informa-

tion and Publishing Centre.

Through the appropriate committee and in accordance with the law,

the National Council of Vlachs seeks to ensure regular provision of infor-

mation in the Vlach language via electronic media (radio programmes, TV

programmes and the internet), whereas in the field of print media is has

been unable to provide information in the mother tongue so far. This will

be changed in the future because the National Council has adopted a pro-

posal for the Vlach script and is looking forward to gradually supplying

members’ needs in the field of print media.

Official Use of Minority Language and Alphabet

Article 22 of the Law on National Councils of National Minorities de-

fines the role of national councils in the field of official use of language

and script. Article 22, paragraph 1 states: [A national council shall: 1)] ‘De-

termine the traditional names of local self-government units, settlements

and other geographical terms in the language of a national minority if this](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-294-2048.jpg)

![384 serbia 2011 :

Di

scr

i

m

i

nat

i

on

2010 Report on the Work of the National Education Council). The Analy-

sis says that the preparatory pre-school programme is attended by 88% of

children although it is compulsory and free of charge. Attendance is low-

est in eastern Serbia (50%) and highest in Vojvodina province (96.4%).

The coverage of children by primary education is about 98%, and in

the last three years 99% of those who have enrolled in primary schools

have graduated. Roma children account for 7.4% of the total number of

enrolled children. Compared with the previous school year, the percent-

age of Roma children enrolled in the first year has increased by some 10%

and of children with developmental handicaps by some 6.6%. The Analy-

sis says that secondary education encompasses some 83% of children. The

secondary schools are attended by fewer children from families where the

head of family has a low level of education and from poor families, by

Roma children and by refugee and internally displaced children.

The share of young people between the ages of 18 and 24 who have

finished only primary school is 30%, compared with the 15% or so of

young people who are leaving education too early in the EU. In Serbia, the

share of pupils dropping out of schooling before finishing secondary edu-

cation in three-year schools is 23.5% and in four-year schools 9.3%. The

majority of dropouts are children from rural environments and poor fam-

ilies and Roma children, the National Education Council says, adding that

precise data is lacking.

The number of children enrolled in the first year of primary schools

in 2011 was 1,897 less than in 2010.651

The percentage of gross domestic product earmarked for education in

Serbia corresponds to the average in the EU. However, most of it is spent

on primary education, as much as twice as much as in the EU. The school

network is uneconomical, with 90% of pupils enrolled in 50% of schools.

Neither the personnel nor the school network is tailored to the demo-

graphic reality. Another problem is the unsatisfactory educational struc-

651

‘[...] this year primary schools are enrolling 76,000 first-year pupils or

1,897 fewer than last year, which is an alarming figure, the minister of

education and science, Žarko Obradović, stressed in Kraljevo yesterday’,

Danas, ‘Alarmantno manji broj prvaka u Srbiji’, 2 September 2011.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-386-2048.jpg)

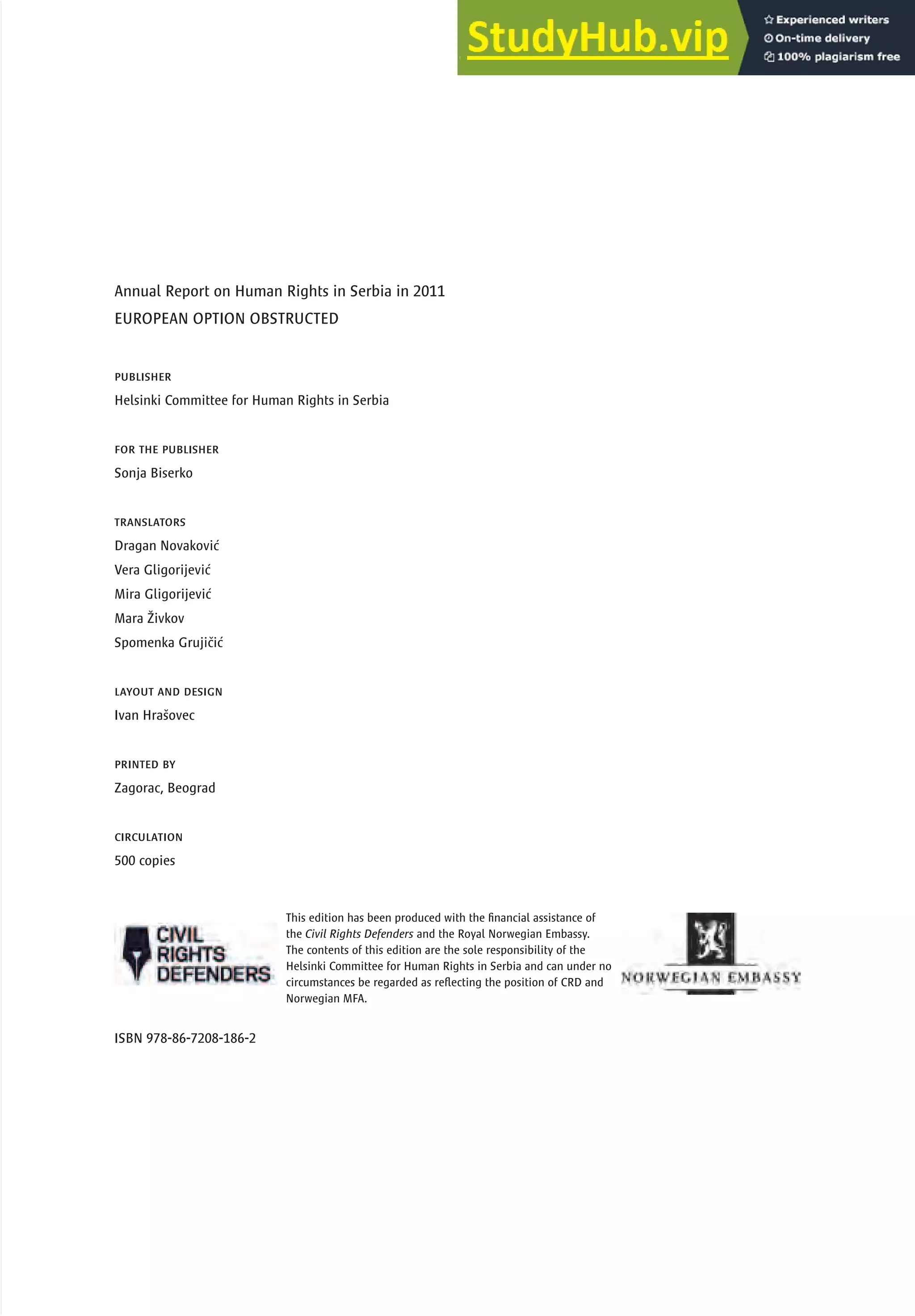

![387

The Young: Escalation of Violence

Peer violence in schools is highly widespread and is far more pronounced

in primary than in secondary schools, according to a survey conducted by

the Protector of Citizens and the Young Advisers Panel on child protection

in schools. The survey encompassed a total of 1,257 respondents in 72 Ser-

bian schools – 37 primary and 35 secondary schools.

As many as 73% of respondents said that peer violence occurred in

their schools frequently, occasionally or rarely. Nearly 90% of primary

school pupils questioned reported having had direct or indirect experi-

ence of peer violence, compared with 60% of their secondary school op-

posite numbers.

Regarding teacher violence against pupils, the survey cites 23% of pri-

mary and secondary school pupils as having witnessed such violence in

some form or another. Unlike peer violence, teacher violence was more in

evidence in secondary schools, indicating that teaching staff were more in-

clined to be violent against older children.653

It is necessary to point out that teachers too are victims of violence at

the hands of pupils in a large number of cases.654

As regards measures aimed at preventing school violence and pupil

participation in them, 60% of respondents said that such measures had

not been implemented in their schools or that they had no knowledge

653 This is testified to by the following media report: ‘[...] the duty judge of the Basic

Court in Loznica yesterday examined B.M., who is suspected of committing in the

school laboratory an indecent act against a pupil [...], Novosti, 24 February 2011.

654 There are more media reports: ‘[...] the latest in the series of violent incidents is the

beating of the 12th Belgrade Grammar School professor, after which the professors held a

protest meeting and repeated their demand for protection of their profession [...]’, Politika,

‘Roditelje ne interesuje nasilje u školi’, 18 January 2001; ‘[…] in the first 10 months of the

year pupils, and also their parents, have carried out 12 attacks on lecturers, principals and

education officers in Belgrade primary and secondary schools’, Kurir, 19 December 2011.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/annualreport2011-230807163344-846e1220/75/Annual-Report-2011-pdf-389-2048.jpg)

![389

The Young: Escalation of Violence

carrying knives in school and so on. The number of junior pupils who