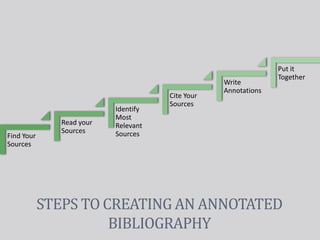

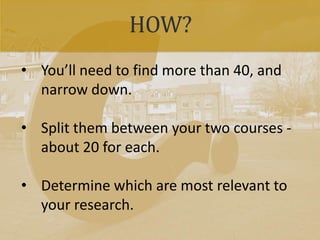

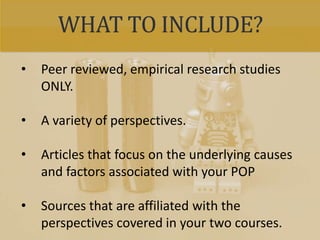

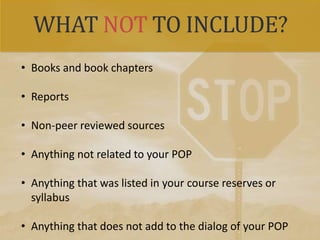

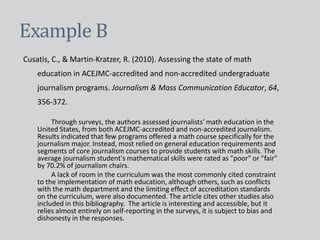

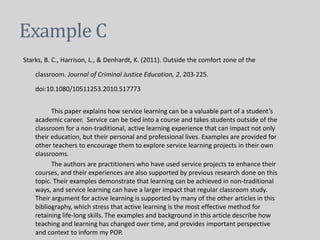

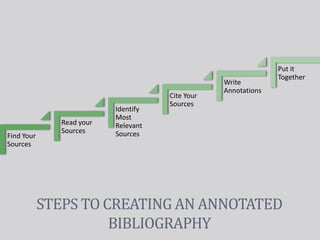

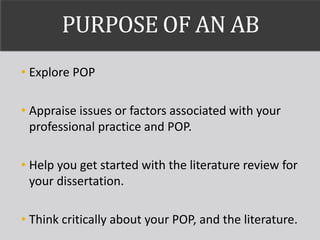

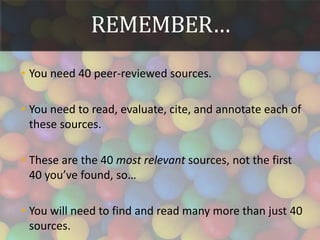

This document provides guidance on creating an annotated bibliography. It begins with a definition of an annotated bibliography as a list of citations followed by an evaluation of each source. It then outlines the six steps to creating an annotated bibliography: finding sources, reading sources, identifying the most relevant sources, citing sources, writing annotations, and putting it all together. Examples of annotations are provided to demonstrate how to summarize sources and evaluate them. The document emphasizes that the purpose of an annotated bibliography is for the student to explore their topic and think critically about the literature in order to help with their dissertation literature review.