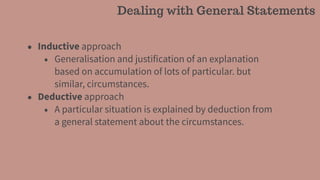

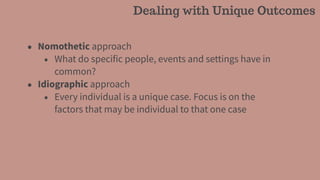

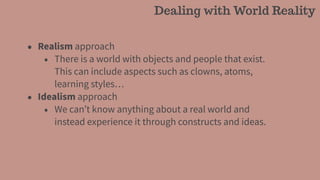

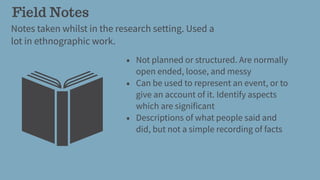

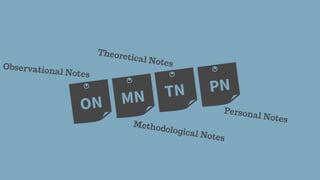

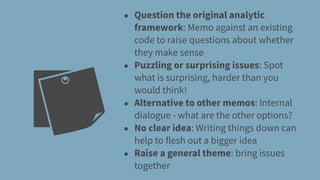

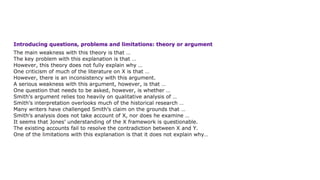

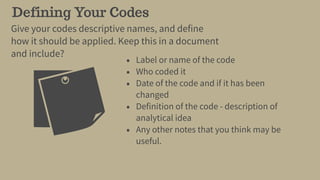

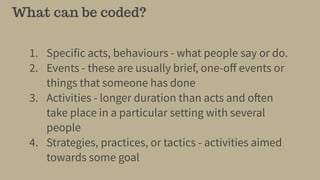

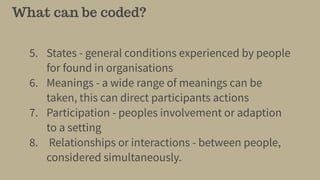

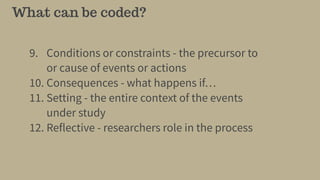

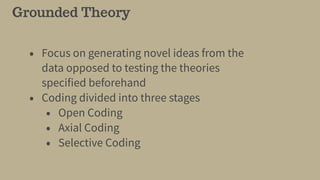

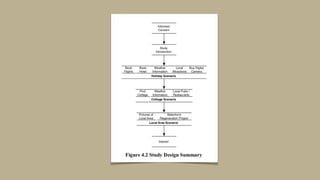

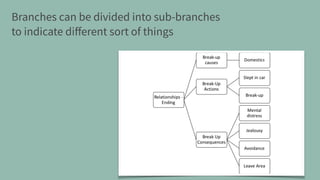

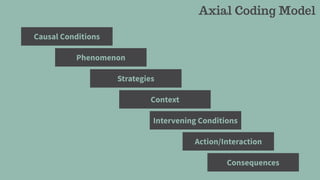

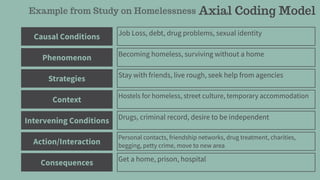

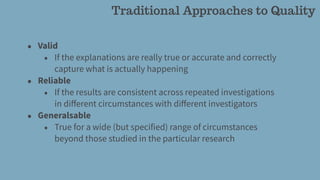

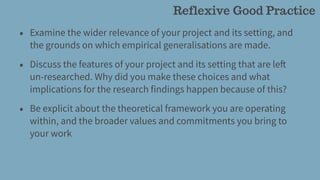

This document provides an overview of qualitative data analysis techniques including inductive and deductive approaches, coding methods like open coding and axial coding, developing code hierarchies, comparative analysis using tables and models, and ensuring analytic quality through reflexivity. It discusses writing as a tool for analysis, such as keeping a research diary, and the importance of anonymity and validity in qualitative research ethics.