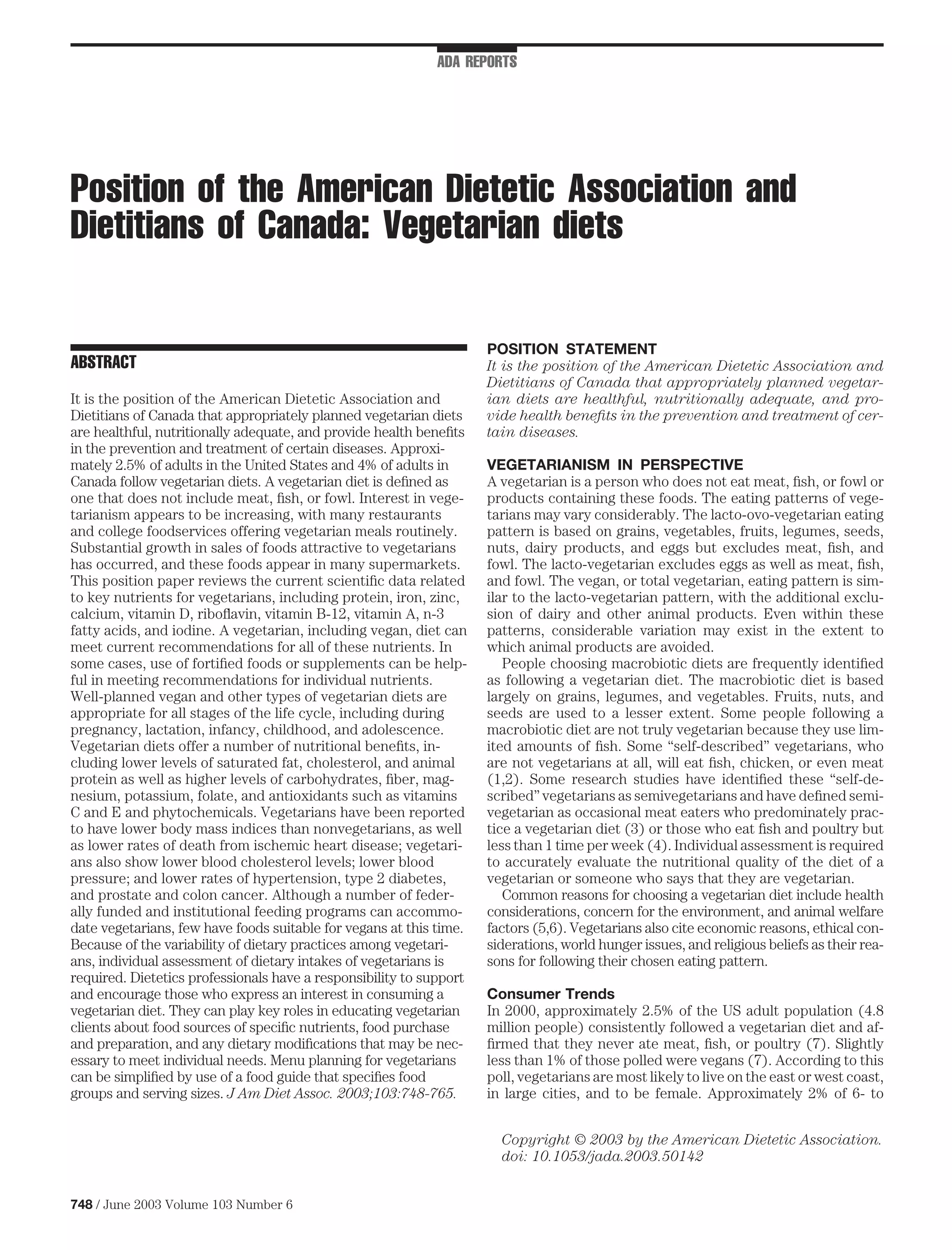

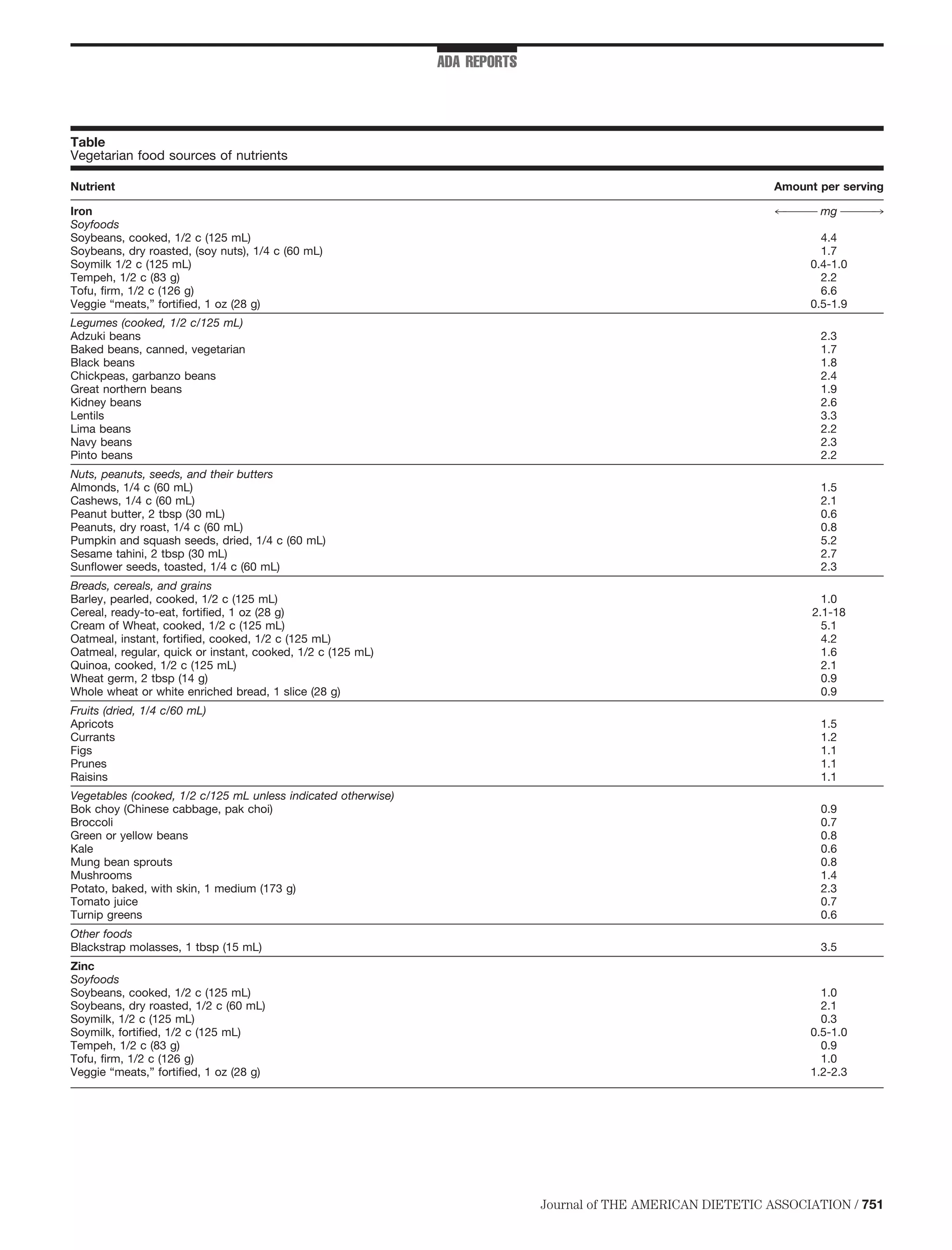

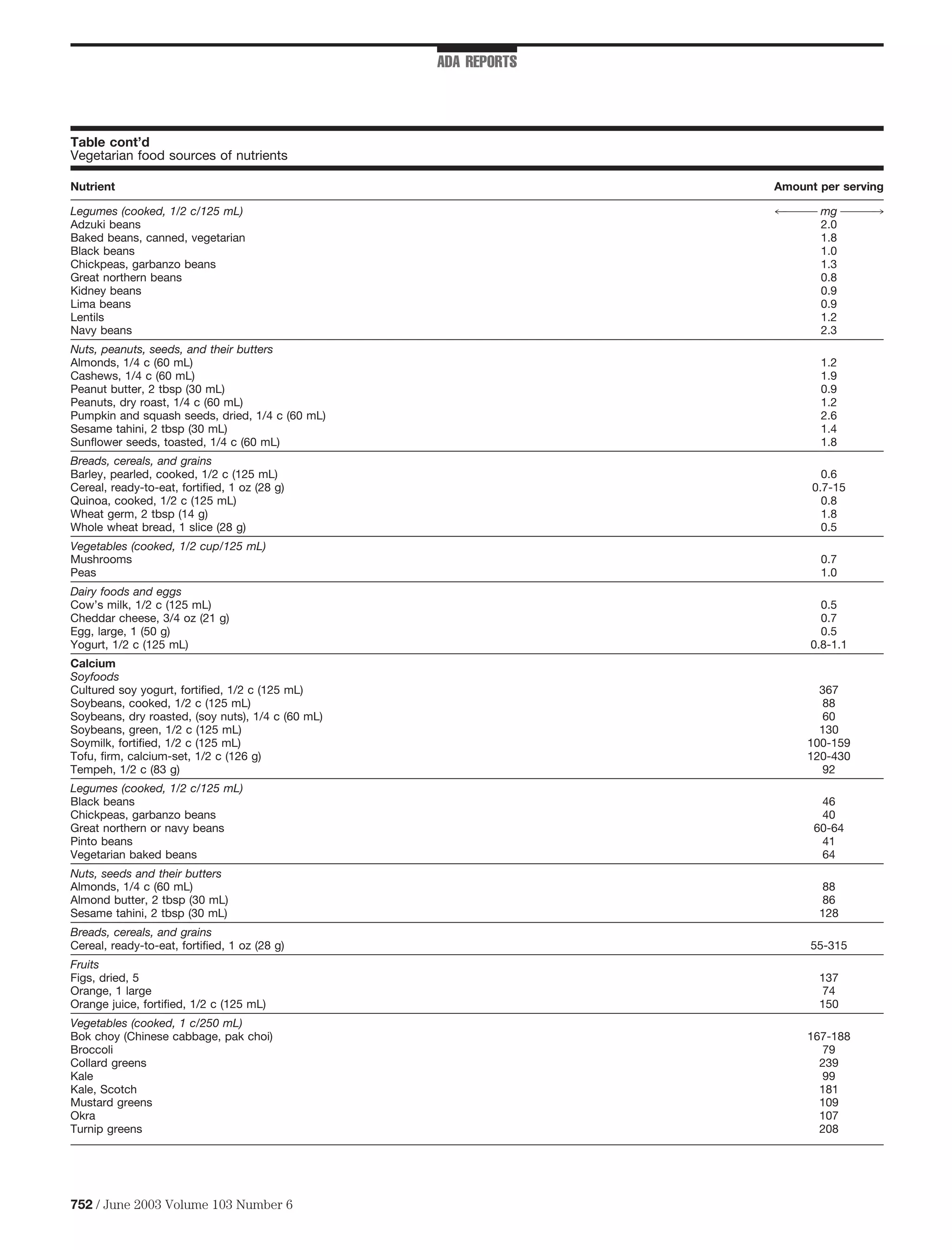

This document summarizes the position of the American Dietetic Association and Dietitians of Canada on vegetarian diets. It finds that appropriately planned vegetarian diets are healthful, nutritionally adequate, and provide health benefits. The document reviews considerations for key nutrients in vegetarian diets and finds that a vegetarian diet can meet recommendations for proteins, iron, zinc, calcium, vitamins B12 and D, and other nutrients when planned properly, potentially with fortified foods or supplements. Vegetarian diets may help reduce risk for heart disease, diabetes, and cancer when based on a variety of plant foods.