This document provides information about the 13th edition of the textbook "Accounting Principles" by Jerry J. Weygandt, Paul D. Kimmel, and Donald E. Kieso. It lists the authors and their academic affiliations. It also provides publication details such as the editor, design team, marketing staff, and copyright information. The brief contents section outlines the chapters included in the textbook. The dedication is to the authors' wives for their love and support.

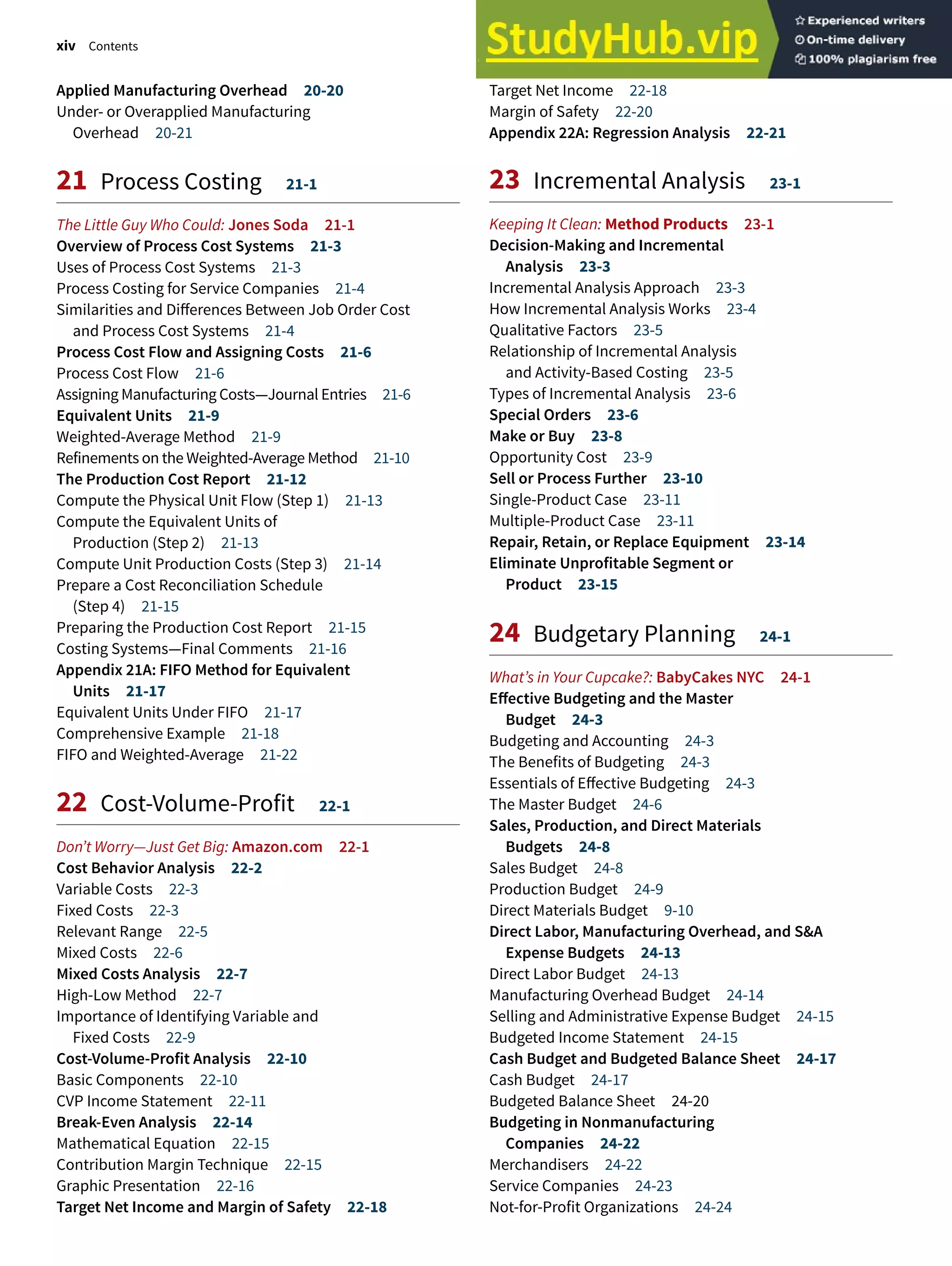

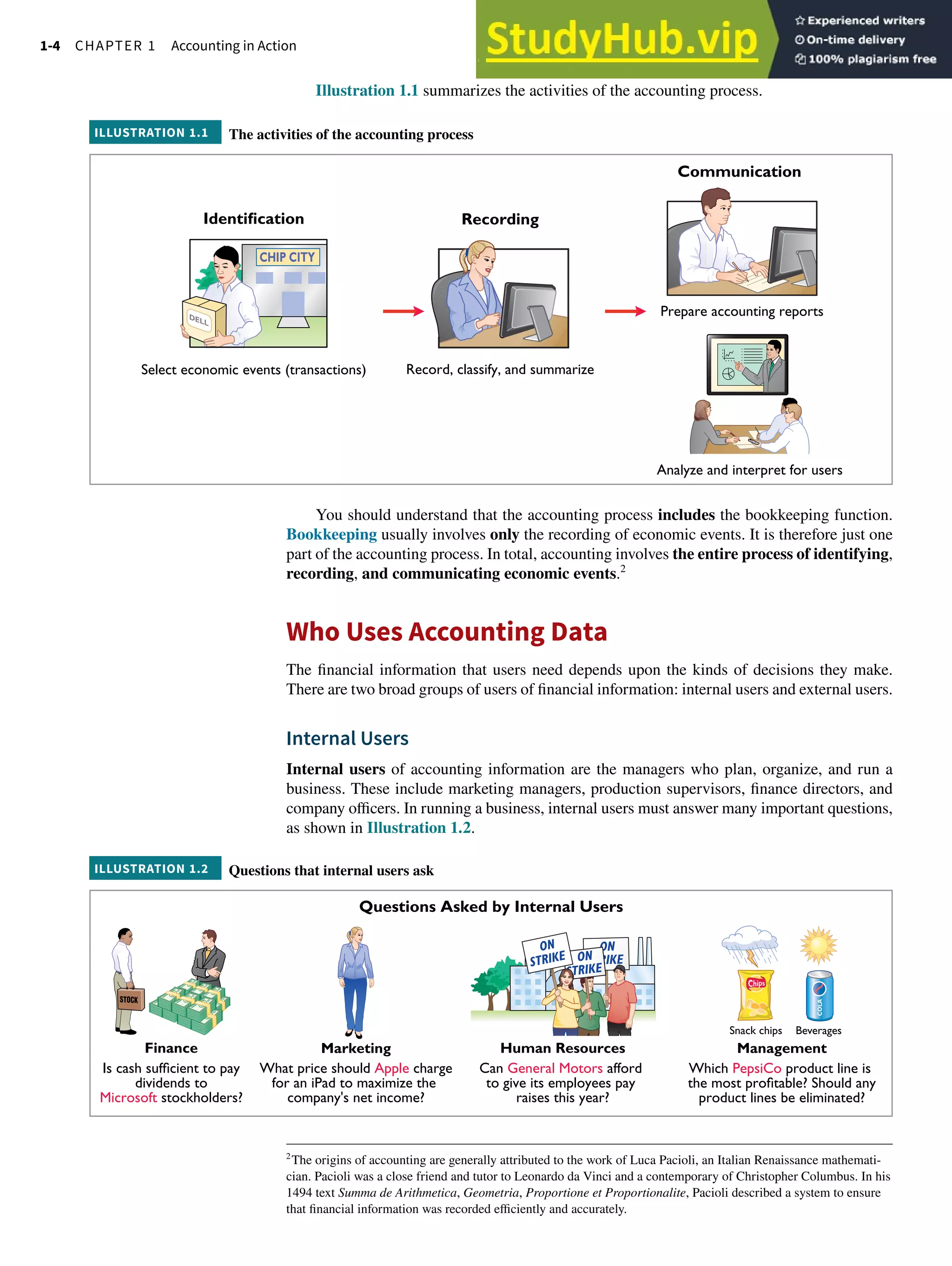

![Analyzing Business Transactions 1-17

The two sides of the equation still balance at $17,800. Owner’s equity decreases when Soft-

byte incurs the expense. Expenses are not always paid in cash at the time they are incurred.

When Softbyte pays at a later date, the liability Accounts Payable will decrease, and the asset

Cash will decrease [see Transaction (8)]. The cost of advertising is an expense (rather than an

asset) because the company has used the benefits. Advertising Expense is included in deter-

mining net income.

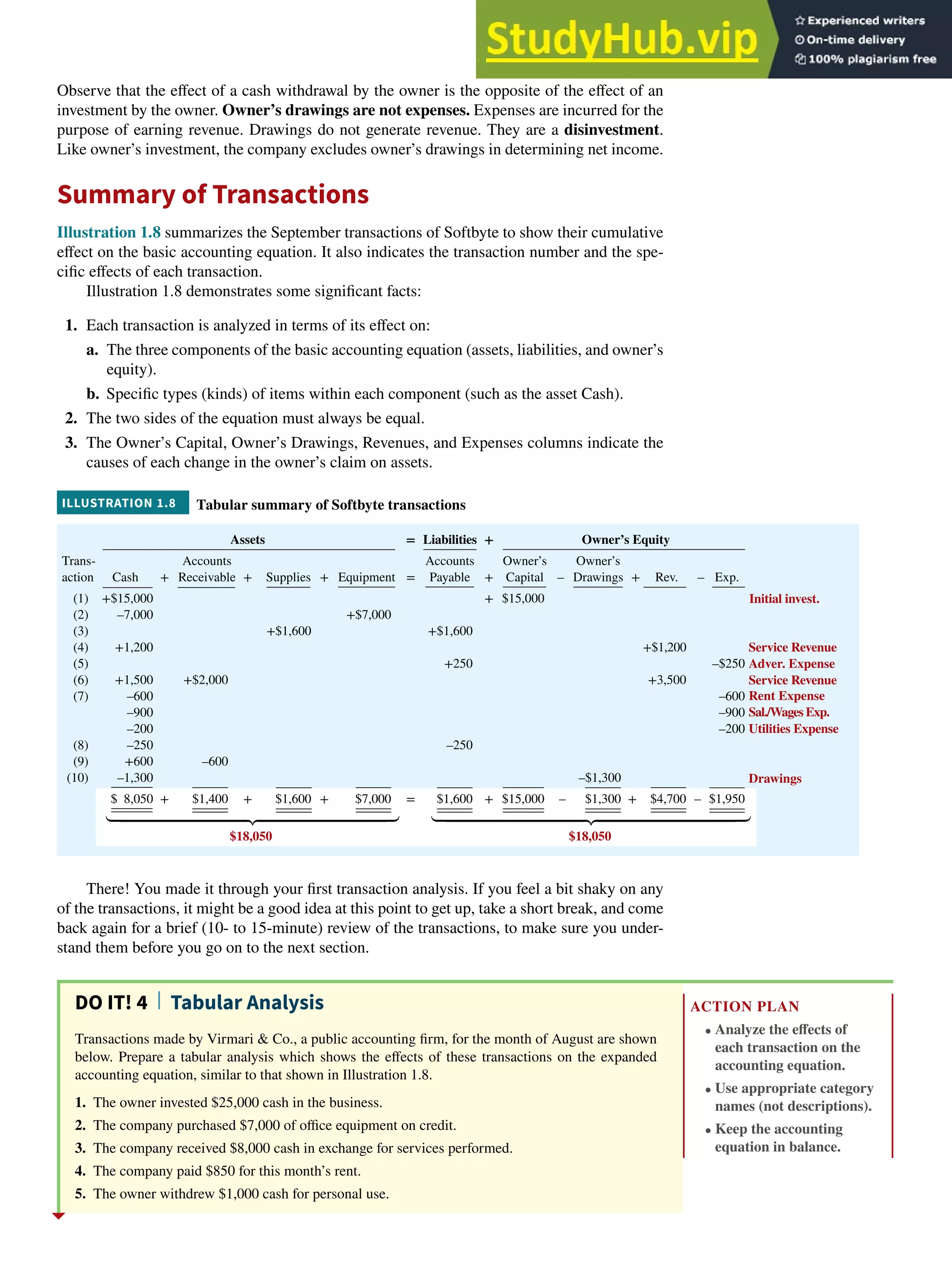

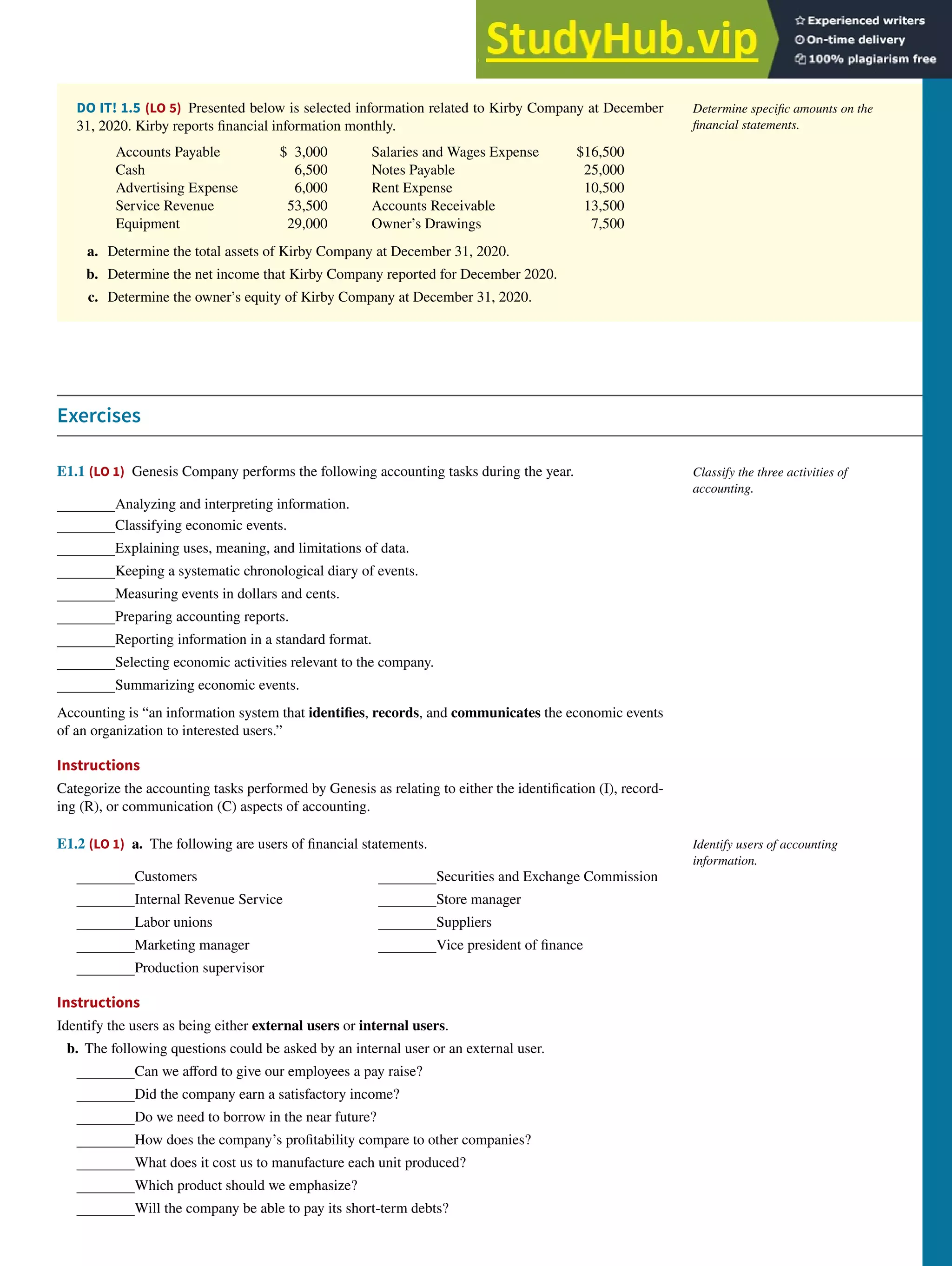

Transaction (6). Services Performed for Cash and Credit. Softbyte performs

$3,500 of app development services for customers. The company receives cash of $1,500

from customers, and it bills the balance of $2,000 on account. This transaction results in an

equal increase in assets and owner’s equity.

Three specific items are affected: The asset Cash increases $1,500, the asset Accounts Receivable increases $2,000,

and owner’s equity increases $3,500 due to Service Revenue.

Basic

Analysis

Equation

Analysis

Assets = Liabilities + Owner’s Equity

Accounts Accounts Owner’s

Cash + Receivable + Supplies + Equipment = Payable + Capital + Revenues – Expenses

$9,200 $1,600 $7,000 $1,850 $15,000 $1,200 $250

(6) +1,500 +$2,000 +3,500

$10,700 + $ 2,000 + $1,600 + $7,000 = $1,850 + $15,000 + $4,700 – $250

$21,300 $21,300

Service

Revenue

⎧

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎨

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎩

⎧

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎨

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎩

Softbyte recognizes $3,500 in revenue when it performs the service. In exchange for

this service, it received $1,500 in Cash and Accounts Receivable of $2,000. This Accounts

Receivable represents customers’ promises to pay $2,000 to Softbyte in the future. When it

later receives collections on account, Softbyte will increase Cash and will decrease Accounts

Receivable [see Transaction (9)].

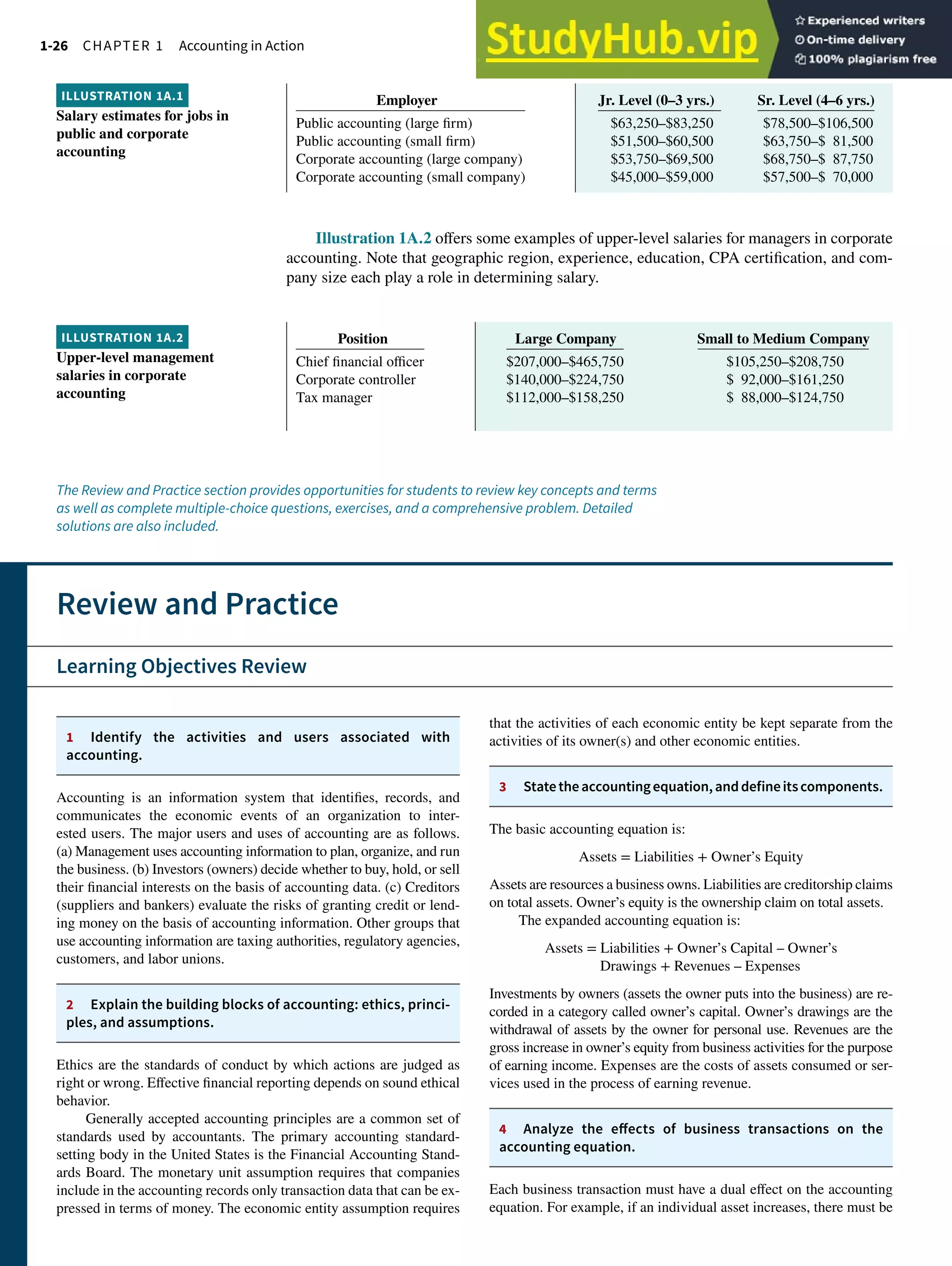

Transaction (7). Payment of Expenses. Softbyte pays the following expenses in cash

for September: office rent $600, salaries and wages of employees $900, and utilities $200.

These payments result in an equal decrease in assets and owner’s equity.

The two sides of the equation now balance at $19,600. Three lines in the analysis indicate the

different types of expenses that have been incurred.

Transaction (8). Payment of Accounts Payable. Softbyte pays its $250 Daily News

bill in cash. The company previously [in Transaction (5)] recorded the bill as an increase in

Accounts Payable and a decrease in owner’s equity.

The asset Cash decreases $1,700, and owner’s equity decreases $1,700 due to the specific expense categories

(Rent Expense, Salaries and Wages Expense, and Utilities Expense).

Basic

Analysis

Equation

Analysis

Assets = Liabilities + Owner’s Equity

Accounts Accounts Owner’s

Cash + Receivable + Supplies + Equipment = Payable + Capital + Revenues – Expenses

$10,700 $2,000 $1,600 $7,000 $1,850 $15,000 $4,700 $ 250

(7) −1,700 −600

−900

−200

$9,000 + $2,000 + $1,600 + $7,000 = $1,850 + $15,000 + $4,700 – $1,950

$19,600 $19,600

Rent Expense

Sal.andWagesExp.

Utilities Exp.

⎧

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎨

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎩

⎧

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎨

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎩](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/accountingprinciplesthirteenthedition-230807181225-90dae868/75/Accounting-Principles-Thirteenth-Edition-pdf-36-2048.jpg)

![1-18 CHAPTER 1 Accounting in Action

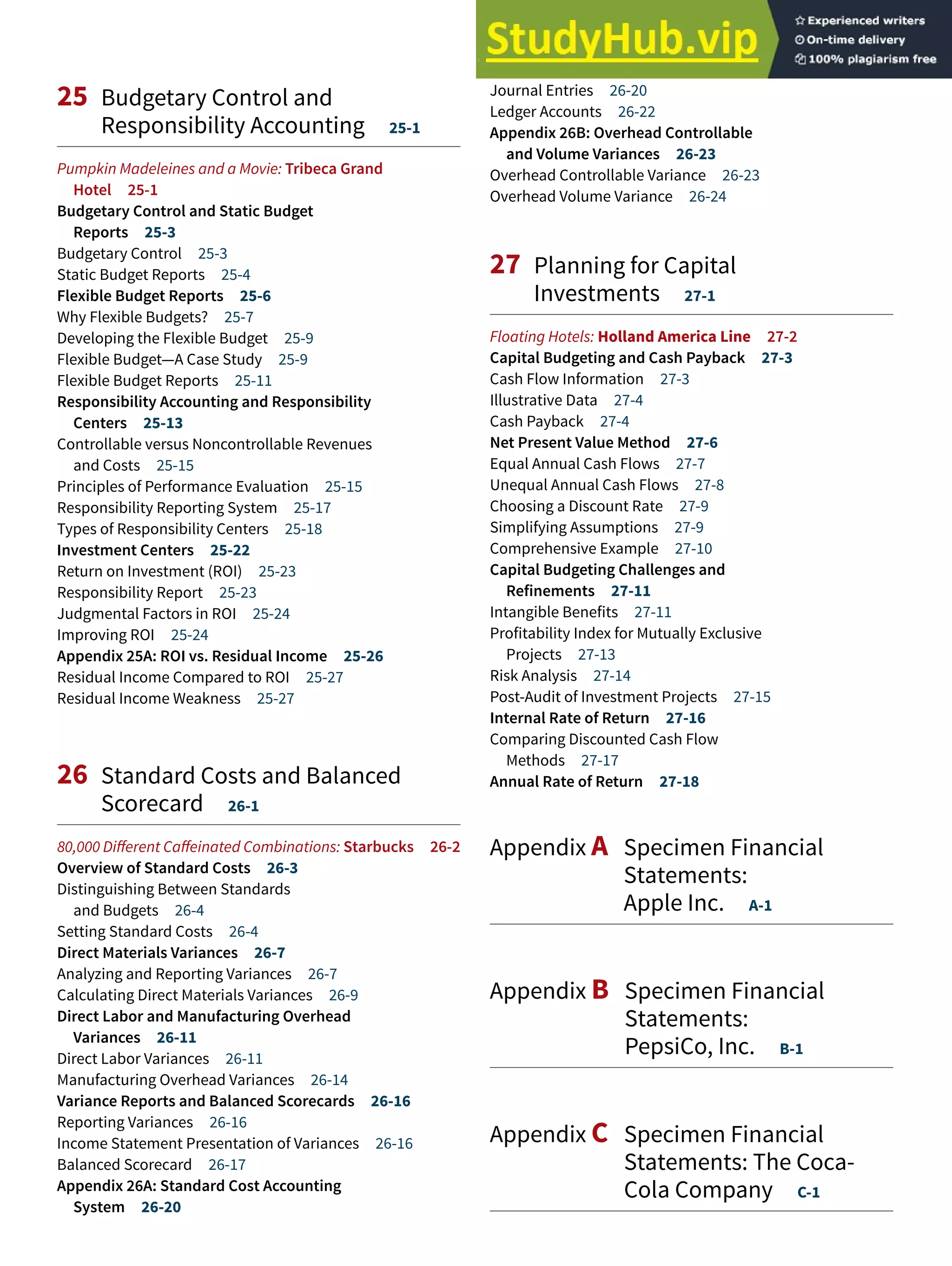

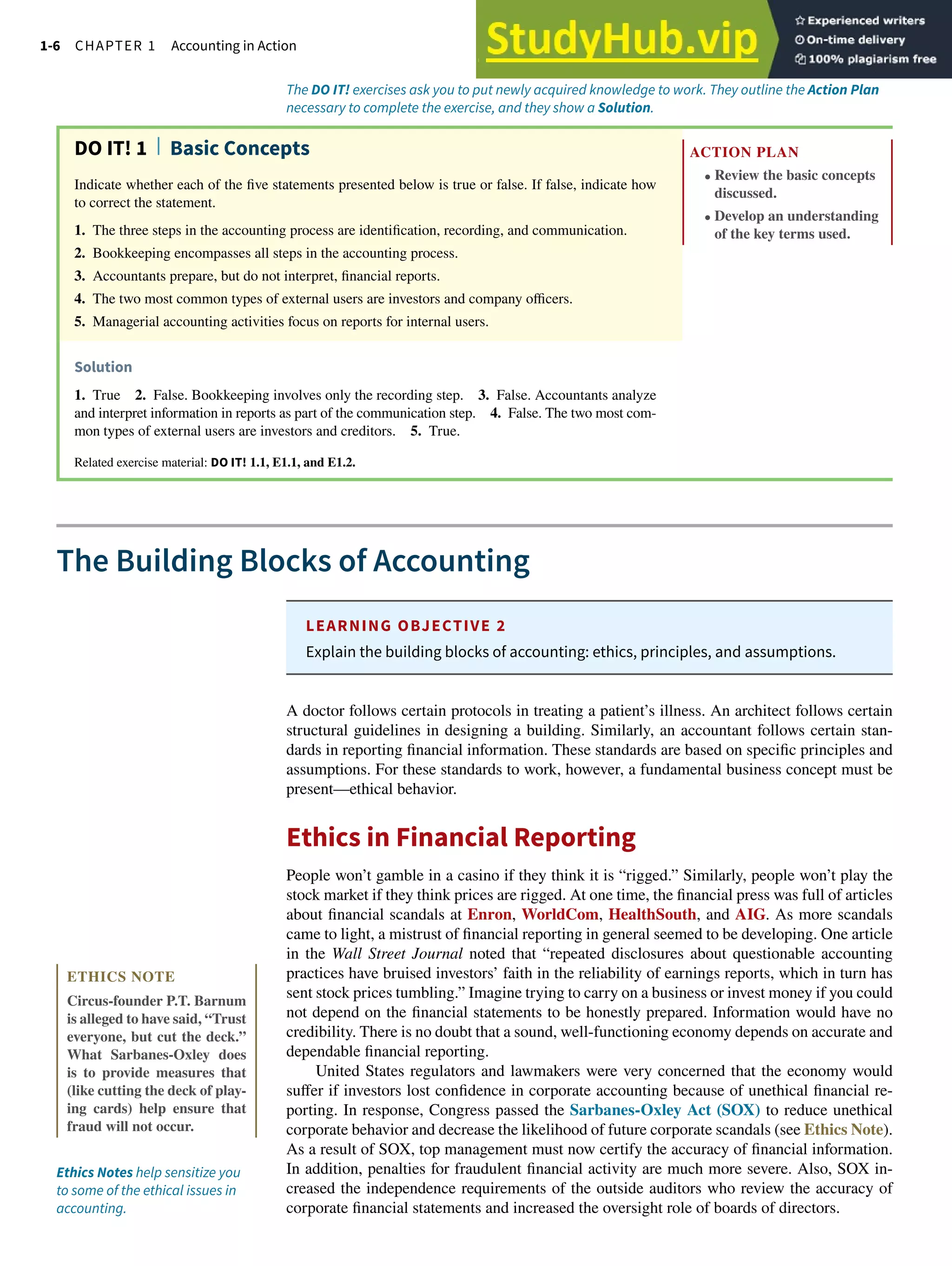

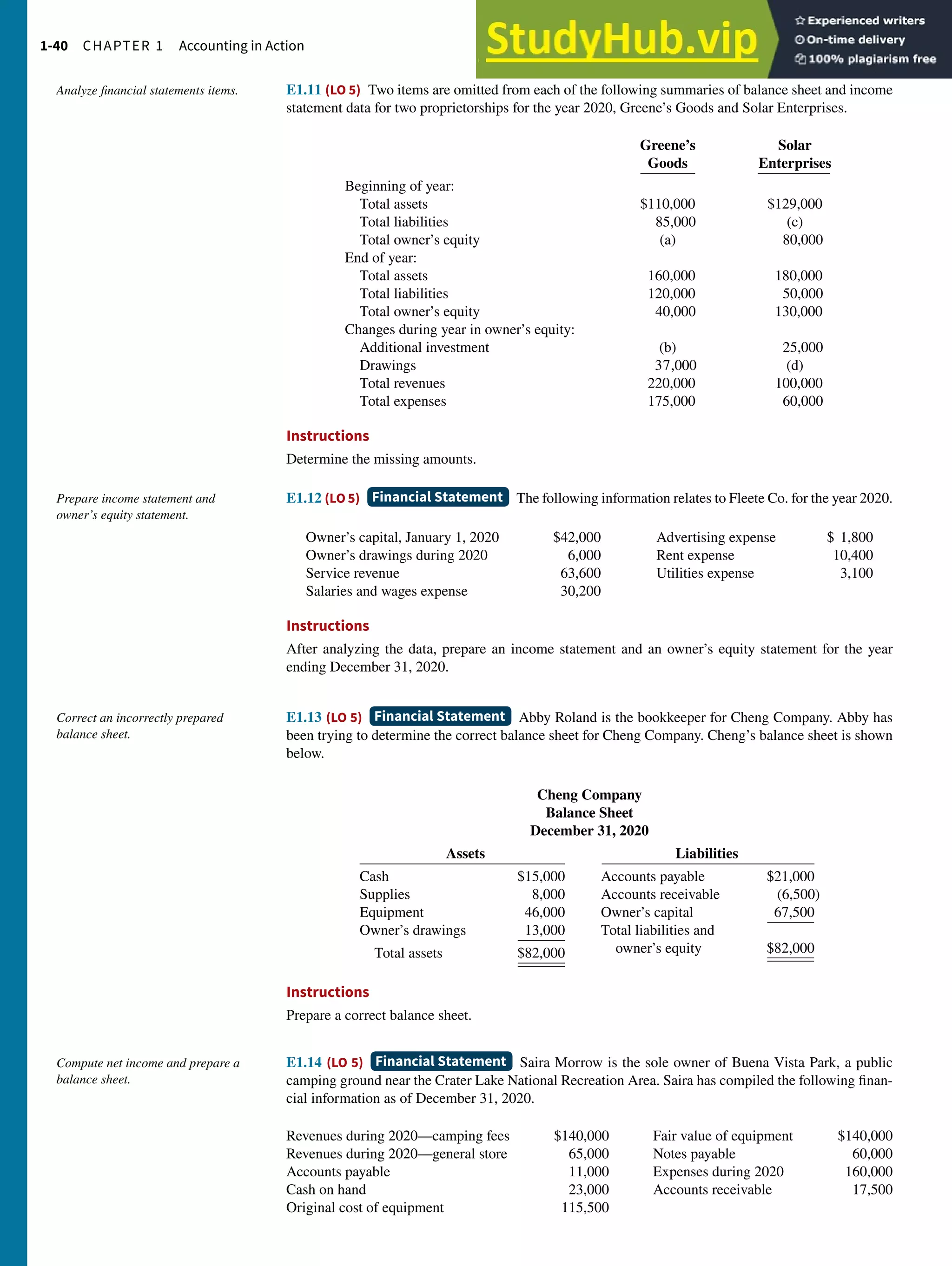

Observe that the payment of a liability related to an expense that has previously been recorded

does not affect owner’s equity. The company recorded this expense in Transaction (5) and

should not record it again.

Transaction (9). Receipt of Cash on Account. Softbyte receives $600 in cash from

customers who had been billed for services [in Transaction (6)]. Transaction (9) does not

change total assets, but it changes the composition of those assets.

Note that the collection of an account receivable for services previously billed and recorded

does not affect owner’s equity. Softbyte already recorded this revenue in Transaction (6) and

should not record it again.

Transaction (10). Withdrawal of Cash by Owner. Ray Neal withdraws $1,300 in

cash from the business for his personal use. This transaction results in an equal decrease in

assets and owner’s equity.

This cash payment “on account” decreases the asset Cash by $250 and also decreases the liability Accounts Payable

by $250.

Basic

Analysis

Equation

Analysis

Assets = Liabilities + Owner’s Equity

Accounts Accounts Owner’s

Cash + Receivable + Supplies + Equipment = Payable + Capital + Revenues – Expenses

$9,000 $2,000 $1,600 $7,000 $1,850 $15,000 $4,700 $1,950

−250 −250

$8,750 + $2,000 + $1,600 + $7,000 = $1,600 + $15,000 + $4,700 – $1,950

$19,350 $19,350

(8) ⎧

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎨

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎩

⎧

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎨

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎩

The asset Cash increases $600, and the asset Accounts Receivable decreases $600.

Basic

Analysis

Equation

Analysis

Assets = Liabilities + Owner’s Equity

Accounts Accounts Owner’s

Cash + Receivable + Supplies + Equipment = Payable + Capital + Revenues – Expenses

$8,750 $2,000 $1,600 $7,000 $1,600 $15,000 $4,700 $1,950

+600 −600

$9,350 + $1,400 + $1,600 + $7,000 = $1,600 + $15,000 + $4,700 – $1,950

$19,350 $19,350

(9)

⎧

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎨

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎩

⎧

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎨

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎩

The asset Cash decreases $1,300, and owner’s equity decreases $1,300 due to owner’s withdrawal (Owner’s

Drawings).

Basic

Analysis

Equation

Analysis

Assets = Liabilities + Owner’s Equity

Accounts Accounts Owner’s Owner’s

Cash + Receivable + Supplies + Equipment = Payable + Capital – Drawings + Revenues – Expenses

$9,350 $1,400 $1,600 $7,000 $1,600 $15,000 $4,700 $1,950

(10) −1,300 −$1,300

$8,050 + $1,400 + $1,600 + $7,000 = $1,600 + $15,000 – $1,300 + $4,700 – $1,950

$18,050 $18,050

Drawings

⎧

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎨

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎩

⎧

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎨

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎩](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/accountingprinciplesthirteenthedition-230807181225-90dae868/75/Accounting-Principles-Thirteenth-Edition-pdf-37-2048.jpg)

![1-24 CHAPTER 1 Accounting in Action

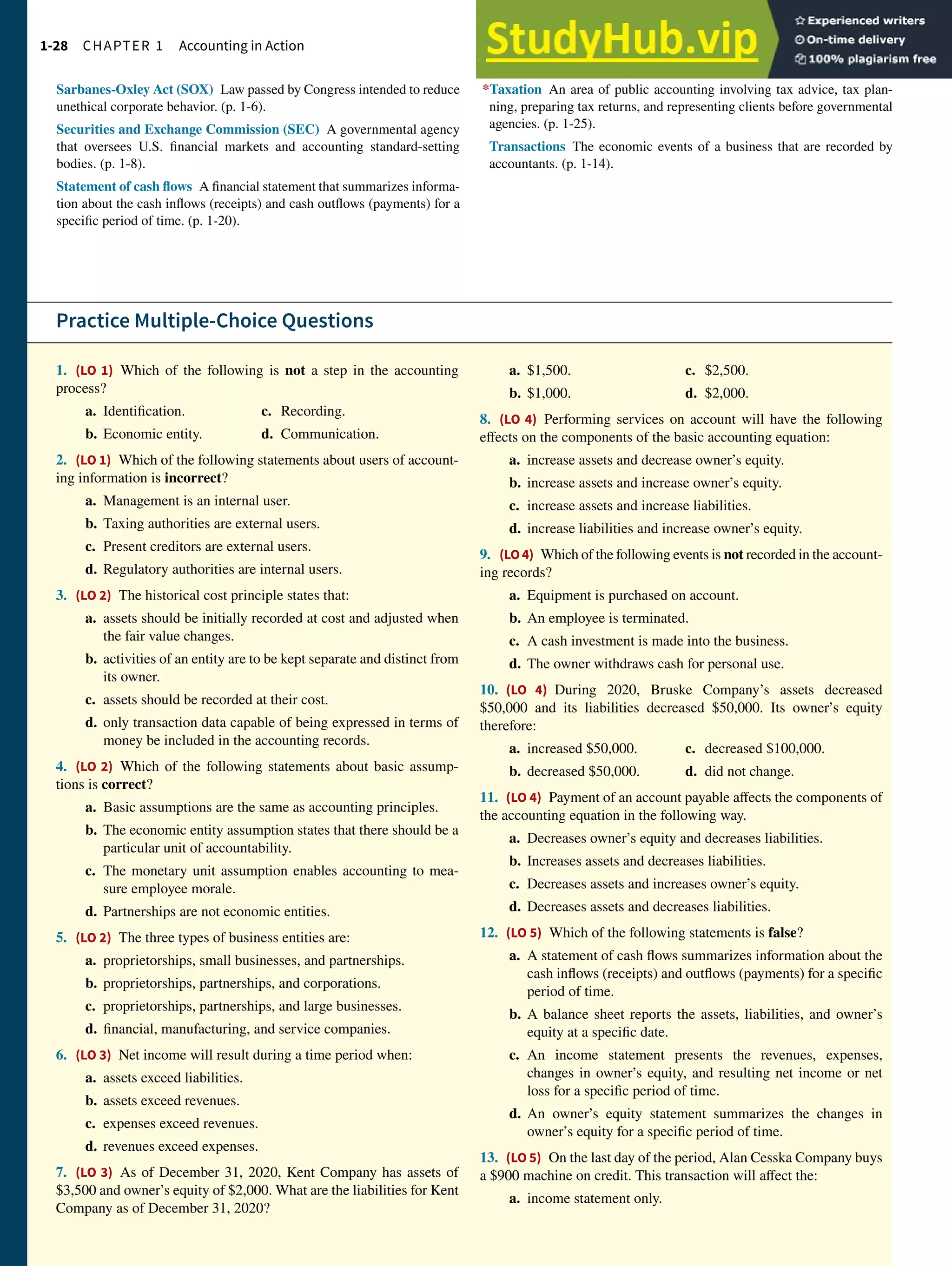

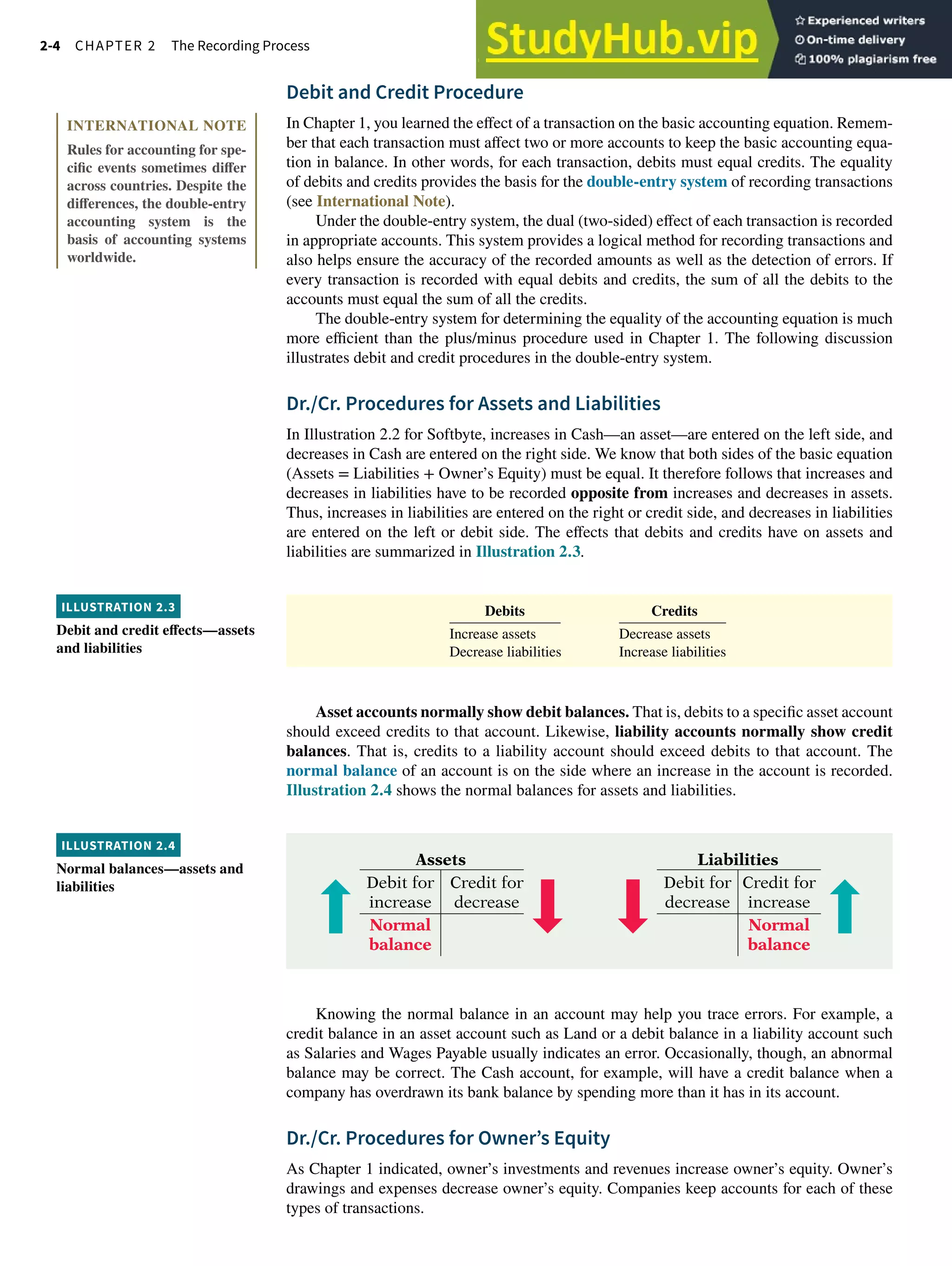

Solution

a. The total assets are $27,000, comprised of Cash $8,000, Accounts Receivable $9,000, and Equip-

ment $10,000.

b. Net income is $14,000, computed as follows.

Revenues

Service revenue $36,000

Expenses

Rent expense $11,000

Salaries and wages expense 7,000

Utilities expense 4,000

Total expenses 22,000

Net income $14,000

c. The ending owner’s equity of Flanagan Company is $8,500. By rewriting the accounting equation,

we can compute owner’s equity as assets minus liabilities, as follows.

Total assets [as computed in (a)] $27,000

Less: Liabilities

Notes payable $16,500

Accounts payable 2,000 18,500

Owner’s equity $ 8,500

Note that it is not possible to determine the company’s owner’s equity in any other way because the

beginning total for owner’s equity is not provided.

Related exercise material: BE1.10, BE1.11, DO IT! 1.5, E1.9, E1.10, E1.11, E1.12, E1.13, E1.14, E1.15, E1.16 ,

E1.17, and E1.18

Appendix 1A Career Opportunities in Accounting

LEARNING OBJECTIVE *6

Explain the career opportunities in accounting.

Why is accounting such a popular major and career choice? First, there are a lot of jobs. In

many cities in recent years, the demand for accountants exceeded the supply. Not only are

there a lot of jobs, but there are a wide array of opportunities. As one accounting organization

observed, “accounting is one degree with 360 degrees of opportunity.”

Accounting is also hot because it is obvious that accounting matters. Interest in accounting

has increased, ironically, because of the attention caused by the accounting failures of compa-

nies such as Enron and WorldCom. These widely publicized scandals revealed the important

role that accounting plays in society. Most people want to make a difference, and an accounting

career provides many opportunities to contribute to society. Finally, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act

(SOX) significantly increased the accounting and internal control requirements for corpora-

tions. This dramatically increased demand for professionals with accounting training.

Accountants are in such demand that it is not uncommon for accounting students to have

accepted a job offer a year before graduation. As the following discussion reveals, the job

options of people with accounting degrees are virtually unlimited.

Public Accounting

Individuals in public accounting offer expert service to the general public, in much the same way

that doctors serve patients and lawyers serve clients. A major portion of public accounting](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/accountingprinciplesthirteenthedition-230807181225-90dae868/75/Accounting-Principles-Thirteenth-Edition-pdf-43-2048.jpg)

![3-48 CHAPTER 3 Adjusting the Accounts

E3.18 (LO 4) Financial Statement The adjusted trial balance for Renfro Company is given in E3.17.

Instructions

Prepare the income and owner’s equity statements for the year and the balance sheet at August 31.

E3.19 (LO 2, 3) The following data are taken from the comparative balance sheets of Bundies Billiards

Club, which prepares its financial statements using the accrual basis of accounting.

December 31 2020 2019

Accounts receivable from members $16,000 $ 8,000

Unearned service revenue 17,000 25,000

Members are billed based upon their use of the club’s facilities. Unearned service revenues arise from

the sale of gift certificates, which members can apply to their future use of club facilities. The 2020 in-

come statement for the club showed that service revenue of $161,000 was earned during the year.

Instructions

(Hint: You will probably find it helpful to use T-accounts to analyze these data.)

a. Prepare journal entries for each of the following events that took place during 2020.

1. Accounts receivable from 2019 were all collected.

2. Gift certificates outstanding at the end of 2019 were all redeemed.

3. An additional $38,000 worth of gift certificates were sold during 2020. A portion of these was

used by the recipients during the year; the remainder was still outstanding at the end of 2020.

4. Services performed for members for 2020 were billed to members.

5. Accounts receivable for 2020 (i.e., those billed in item [4] above) were partially collected.

b. Determine the amount of cash received by the club, with respect to member services, during 2020.

*E3.20 (LO 5) Bob Zeller Company has the following balances in selected accounts on December 31,

2020.

Service Revenue $40,000

Insurance Expense 2,400

Supplies Expense 2,450

All the accounts have normal balances. Bob Zeller Company debits prepayments to expense accounts

when paid, and credits unearned revenues to revenue accounts when received. The following information

below has been gathered at December 31, 2020.

1. Bob Zeller Company paid $2,400 for 12 months of insurance coverage on June 1, 2020.

2. On December 1, 2020, Bob Zeller Company collected $40,000 for consulting services to be per-

formed from December 1, 2020, through March 31, 2021.

3. A count of supplies on December 31, 2020, indicates that supplies of $600 are on hand.

Instructions

Prepare the adjusting entries needed at December 31, 2020.

*E3.21 (LO 5) At Sekon Company, prepayments are debited to expense when paid, and unearned reve-

nues are credited to revenue when cash is received. During January of the current year, the following

transactions occurred.

Jan. 2 Paid $1,920 for fire insurance protection for the year.

10 Paid $1,700 for supplies.

15 Received $6,100 for services to be performed in the future.

On January 31, it is determined that $2,100 of the services were performed and that there are $650 of

supplies on hand.

Instructions

a. Journalize and post the January transactions. (Use T-accounts.)

b. Journalize and post the adjusting entries at January 31.

c. Determine the ending balance in each of the accounts.

Prepare financial statements from

adjusted trial balance.

Record transactions on accrual basis;

convert revenue to cash receipts.

Journalize adjusting entries.

Journalize transactions and adjusting

entries.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/accountingprinciplesthirteenthedition-230807181225-90dae868/75/Accounting-Principles-Thirteenth-Edition-pdf-163-2048.jpg)

![5-34 CHAPTER 5 Accounting for Merchandising Operations

Solutions

1. c. Gross profit will result if net sales are greater than cost of goods

sold. The other choices are incorrect because (a) operating expenses

and net income are not used in the computation of gross profit; (b)

gross profit results when net sales are greater than cost of goods sold,

not operating expenses; and (d) gross profit results when net sales,

not operating expenses, are greater than cost of goods sold.

2. a. Under a perpetual inventory system, when a company pur-

chases goods for resale, purchases on account are debited to the

Inventory account, not (b) Purchases or (c) Purchase Returns and

Allowances. Choice (d) is incorrect because freight costs are also

debited to the Inventory account, not the Freight-Out account.

3. c. Both Sales Discounts and Sales Returns and Allowances nor-

mally have a debit balance. Choices (a) and (b) are both correct, but

(c) is the better answer. Choice (d) is incorrect as both (a) and (b) are

correct.

4. b. The full amount of $686 is paid within 10 days of the pur-

chase ($750 – $50) – [($750 – $50) × 2%]. The other choices are

incorrect because (a) does not consider the discount of $14; (c) the

amount of the discount is based upon the amount after the return

is granted ($700 × 2%), not the amount before the return of mer-

chandise ($750 × 2%); and (d) does not constitute payment in full

on June 23.

5. c. The Cost of Goods Sold account normally appears in the ledger

of a merchandising company using a perpetual inventory system.

The other choices are incorrect because (a) the Purchases account,

(b) the Freight-In account, and (d) the Purchase Discounts account all

appear in the ledger of a merchandising company that uses a periodic

inventory system.

6. c. Two journal entries are necessary: one to record the receipt

of cash and sales revenue, and one to record the cost of goods sold

and reduction of inventory. The other choices are incorrect because

(a) only considers the recognition of the expense and ignores the rev-

enue, (b) only considers the recognition of revenue and leaves out the

expense or cost of merchandise sold, and (d) the receipt of cash and

sales revenue, not reduction of inventory, are paired together, and the

cost of goods sold and reduction of inventory, not sales revenue, are

paired together.

7. a. An additional adjusting journal entry for inventory may be

needed in a merchandising company to adjust for a physical inventory

count, but it is not needed for a service company. The other choices

are incorrect because (b) closing journal entries and (c) a post-

closing trial balance are required for both types of companies. Choice

(d) is incorrect because while a multiple-step income statement is

not required for a merchandising company, it is useful to distinguish

income generated from operating the business versus income or loss

from non-recurring, nonoperating items.

8. d. An investing activities section appears on the statement

of cash flows, not on a multiple-step income statement. Choices

(a) gross profit, (b) cost of goods sold, and (c) a sales section are all

features of a multiple-step income statement.

9. b. Gross profit = Net sales ($400,000) – Cost of goods sold

($310,000) = $90,000, not (a) $30,000, (c) $340,000, or (d) $400,000.

10. c. Both sales revenue and “Other revenues and gains” are

reported in the revenues section of a single-step income statement.

The other choices are incorrect because (a) gross profit is not reported

on a single-step income statement, (b) cost of goods sold is included

in the expenses section of a single-step income statement, and

(d) income from operations is not shown separately on a single-step

income statement.

11. d. Cost of goods sold appears on both a single-step and a

multiple-step income statement. The other choices are incorrect

because (a) inventory does not appear on either a single-step or a

multiple-step income statement and (b) gross profit and (c) income

from operations appear on a multiple-step income statement but not

on a single-step income statement.

12. a. In a worksheet using a perpetual inventory system, inven-

tory is shown in the adjusted trial balance debit column and in

the balance sheet debit column. The other choices are incorrect

because the Inventory account is not shown in the income state-

ment columns.

*13. d. In determining cost of goods sold in a periodic system,

freight-in is added to net purchases. The other choices are incorrect

because (a) purchase discounts are deducted from purchases, not net

purchases; (b) freight-out is a cost of sales, not a cost of purchases;

and (c) purchase returns and allowances are deducted from purchases,

not net purchases.

*14. a. Beginning inventory ($60,000) + Cost of goods purchased

($380,000) – Ending inventory ($50,000) = Cost of goods sold

($390,000), not (b) $370,000, (c) $330,000, or (d) $420,000.

*15. b. Purchases for resale are debited to the Purchases account.

The other choices are incorrect because (a) purchases on account

are debited to Purchases, not Inventory; (c) Purchase Returns and

Allowances are always credited; and (d) freight costs are debited to

Freight-In, not Purchases.

Practice Brief Exercises

1. (LO 1) Presented below are the components in determining cost of goods sold for (a) Frazier

Company, (b) Todd Company, and (c) Abreu Enterprises. Determine the missing amounts.

Beginning Cost of Goods Ending Cost of

Inventory Purchases Available for Sale Inventory Goods Sold

a. $120,000 $150,000 ? ? $160,000

b. $ 50,000 ? $125,000 $45,000 ?

c. ? $220,000 $330,000 $61,000 ?

Compute the missing amounts in

determining cost of goods sold.

Solution

1. a. Cost of goods available for sale = $120,000 + $150,000 = $270,000

Ending inventory = $270,000 – $160,000 = $110,000](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/accountingprinciplesthirteenthedition-230807181225-90dae868/75/Accounting-Principles-Thirteenth-Edition-pdf-271-2048.jpg)

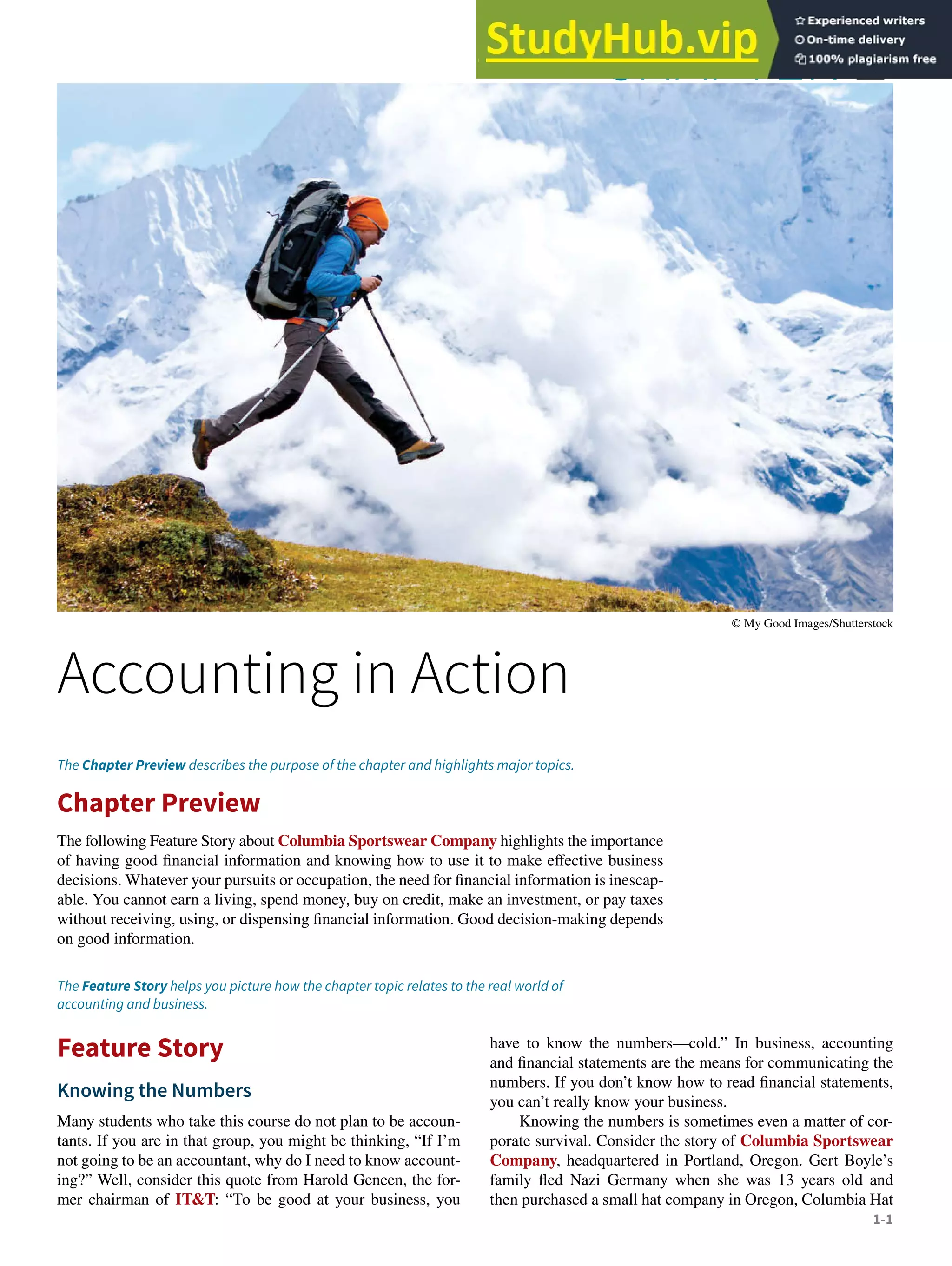

![Effects of Inventory Errors 6-15

DO IT! 2 Cost Flow Methods

The accounting records of Shumway Ag Implements show the following data.

Beginning inventory 4,000 units at $ 3

Purchases 6,000 units at $ 4

Sales 7,000 units at $12

Determine the cost of goods sold during the period under a periodic inventory system using (a) the

FIFO method, (b) the LIFO method, and (c) the average-cost method.

ACTION PLAN

• Understand the periodic

inventory system.

• Allocate costs between

goods sold and goods on

hand (ending inventory)

for each cost flow method.

• Compute cost of goods sold

for each method.

Solution

Cost of goods available for sale = (4,000 × $3) + (6,000 × $4) = $36,000

Ending inventory = 10,000 − 7,000 = 3,000 units

a. FIFO: $36,000 − (3,000 × $4) = $24,000

b. LIFO: $36,000 − (3,000 × $3) = $27,000

c. Average cost per unit: [(4,000 @ $3) + (6,000 @ $4)] ÷ 10,000 = $3.60

Average-cost: $36,000 − (3,000 × $3.60) = $25,200

Related exercise material: BE6.3, BE6.4, BE6.5, BE6.6, DO IT! 6.2, E6.4, E6.5, E6.6, E6.7, E6.8, and E6.9.

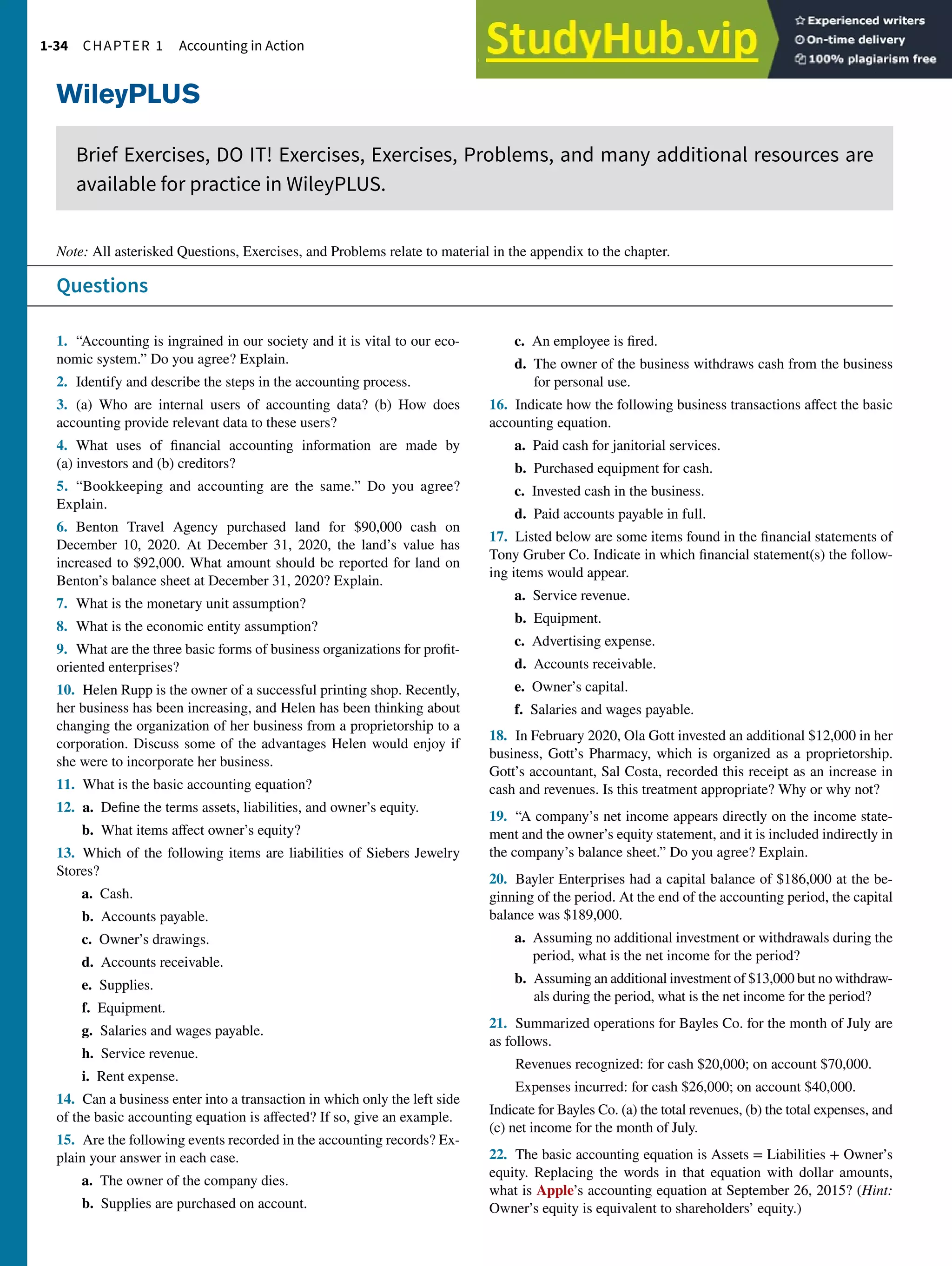

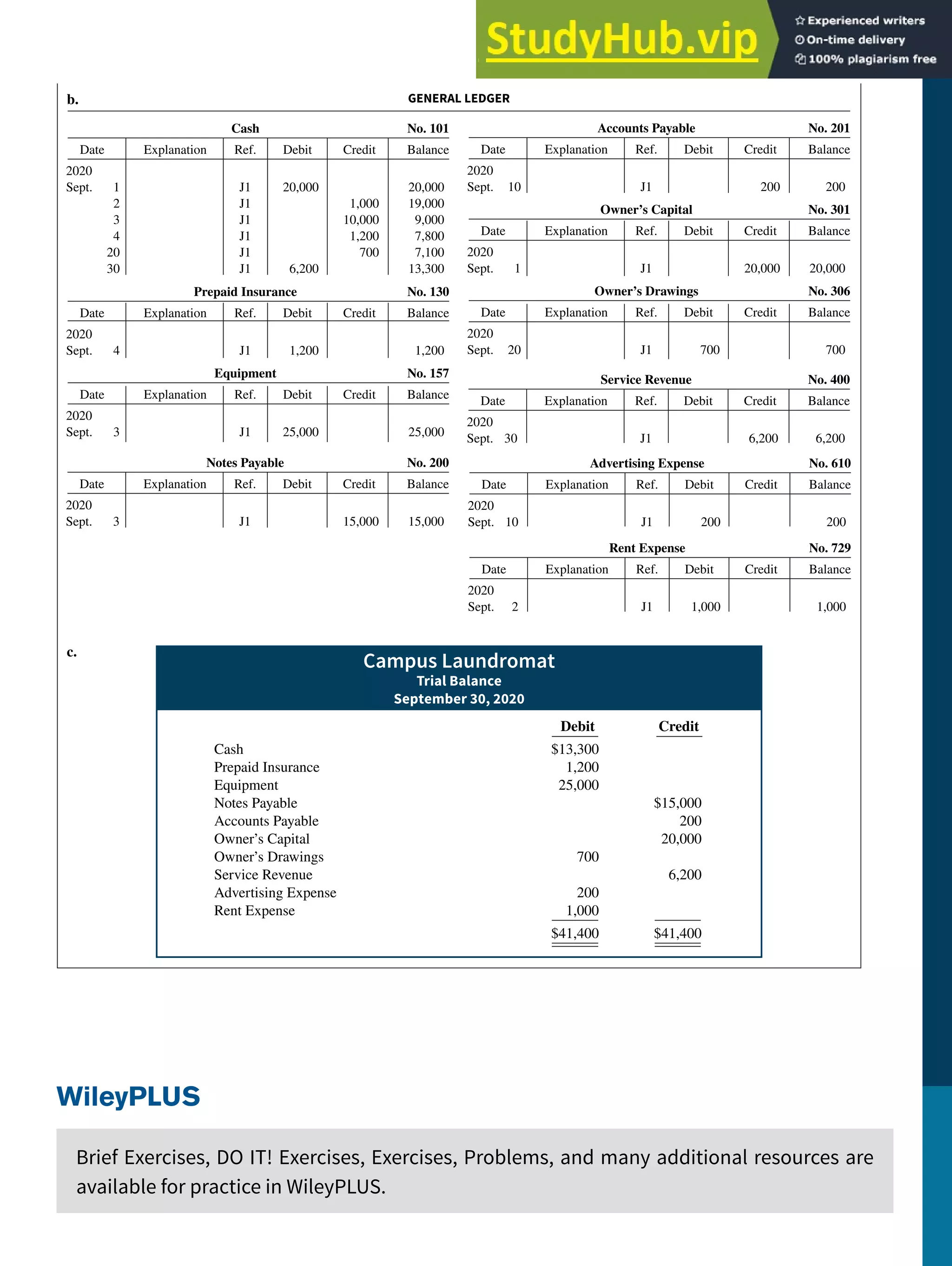

Effects of Inventory Errors

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 3

Indicate the effects of inventory errors on the financial statements.

Unfortunately, errors occasionally occur in accounting for inventory. In some cases, errors are

caused by failure to count or price the inventory correctly. In other cases, errors occur because

companies do not properly recognize the transfer of legal title to goods that are in transit.

When errors occur, they affect both the income statement and the balance sheet.

Income Statement Effects

The ending inventory of one period automatically becomes the beginning inventory of the

next period. Thus, inventory errors affect the computation of cost of goods sold and net in-

come in two periods.

The effects on cost of goods sold can be computed by first entering incorrect data in the

formula in Illustration 6.15 and then substituting the correct data.

Beginning

Cost of

Ending

Cost of

+ Goods − = Goods

Inventory

Purchased

Inventory

Sold

ILLUSTRATION 6.15

Formula for cost of goods sold

If beginning inventory is understated, cost of goods sold will be understated. If ending

inventory is understated, cost of goods sold will be overstated. Illustration 6.16 shows the

effects of inventory errors on the current year’s income statement.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/accountingprinciplesthirteenthedition-230807181225-90dae868/75/Accounting-Principles-Thirteenth-Edition-pdf-308-2048.jpg)

![Appendix 6A: Inventory Methods and the Perpetual System 6-21

Balance

Date Purchases Cost of Goods Sold (in units and cost)

January 1 (100 @ $10) $1,000

April 15 (200 @ $11) $2,200 (100 @ $10)

(200 @ $11)

$3,200

August 24 (300 @ $12) $3,600 (100 @ $10)

(200 @ $11) $6,800

(300 @ $12)

September 10 (300 @ $12)

(200 @ $11)

( 50 @ $10) (50 @ $10) $ 500

$6,300

November 27 (400 @ $13) $5,200 (50 @ $10)

$5,700

(400 @ $13)

The ending inventory in this situation is $5,800, and the cost of goods sold is $6,200 [(100 @

$10) + (200 @ $11) + (250 @ $12)].

Compare Illustrations 6.6 and 6A.2. You can see that the results under FIFO in a per-

petual system are the same as in a periodic system. In both cases, the ending inventory is

$5,800 and cost of goods sold is $6,200. Regardless of the system, the first costs in are the

costs assigned to cost of goods sold.

Last-In, First-Out (LIFO)

Under the LIFO method using a perpetual system, the company charges to cost of goods sold

the cost of the most recent purchase prior to sale. Therefore, the cost of the goods sold on

September 10 consists of all the units from the August 24 and April 15 purchases plus 50 of the

units in beginning inventory. Illustration 6A.3 shows the computation of the ending inventory

under the LIFO method.

Balance

Date Purchases Cost of Goods Sold (in units and cost)

January 1 (100 @ $10) $1,000

April 15 (200 @ $11) $2,200 (100 @ $10)

(200 @ $11)

$3,200

August 24 (300 @ $12) $3,600 (100 @ $10)

(200 @ $11) $6,800

(300 @ $12)

September 10 (100 @ $10)

(200 @ $11)

(250 @ $12) ( 50 @ $12) $ 600

$6,200

November 27 (400 @ $13) $5,200 ( 50 @ $12)

$5,800

(400 @ $13) Ending inventory

Cost of goods sold

⎧

⎪

⎪

⎨

⎪

⎪

⎩

⎧

⎨

⎩

⎧

⎨

⎩

⎧

⎪

⎨

⎪

⎩

ILLUSTRATION 6A.2

Perpetual system—FIFO

Ending inventory

Cost of goods sold

⎧

⎪

⎨

⎪

⎩

⎧

⎨

⎩

⎧

⎪

⎨

⎪

⎩

⎧

⎨

⎩

ILLUSTRATION 6A.3

Perpetual system—LIFO

The use of LIFO in a perpetual system will usually produce cost allocations that differ

from those using LIFO in a periodic system. In a perpetual system, the latest units purchased

prior to each sale are allocated to cost of goods sold. In contrast, in a periodic system, the

latest units purchased during the period are allocated to cost of goods sold. Thus, when a

purchase is made after the last sale, the LIFO periodic system will apply this purchase to the

previous sale.

See Illustration 6.9, which shows the proof that the 400 units at $13 purchased on

November 27 applied to the sale of 550 units on September 10.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/accountingprinciplesthirteenthedition-230807181225-90dae868/75/Accounting-Principles-Thirteenth-Edition-pdf-314-2048.jpg)

![6-28 CHAPTER 6 Inventories

Practice Brief Exercises

1. (LO 2) In its first month of operations, Moncada Company made three purchases of merchandise

in the following sequence: (1) 200 units at $7, (2) 300 units at $8, and (3) 150 units at $9. Assuming

there are 220 units on hand, compute the cost of the ending inventory under the (a) FIFO method and

(b) LIFO method. Moncada uses a periodic inventory system.

Compute ending inventory using

FIFO and LIFO.

Solution

1. a. The ending inventory under FIFO consists of (150 units at $9) + (70 units at $8) for a total

allocation of $1,910 ($1,350 + $560).

b. The ending inventory under LIFO consists of (200 units at $7) + (20 units at $8) for a total

allocation of $1,560 ($1,400 + $160).

11. b. Owner’s equity is overstated by $15,000 at December 31,

2019, and is properly stated at December 31, 2020. An ending inven-

tory error in one period will have an equal and opposite effect on cost

of goods sold and net income in the next period; after two years, the

errors have offset each other. The other choices are incorrect because

owner’s equity (a) is properly stated, not understated, at December 31,

2020; (c) is overstated, not understated, by $15,000 at December 31,

2019, and is properly stated, not understated, at December 31, 2020;

and (d) is properly stated at December 31, 2020, not overstated.

12. a. Conservatism means to use the lowest value for assets and

revenues when in doubt. The other choices are incorrect because

(b) historical cost means that companies value assets at the original

cost, (c) materiality means that an amount is large enough to affect a

decision-maker, and (d) economic entity means to keep the company’s

transactions separate from the transactions of other entities.

13. d. Under the LCNRV basis, net realizable value is defined

as the estimated selling price in the normal course of business,

less estimated costs to complete and sell. Therefore, ending inven-

tory would be valued at 200 widgets × $80 each = $16,000 not

(a) $91,000, (b) $80,000, or (c) $18,200.

14. b. Santana’s days in inventory = 365/Inventory turnover = 365/

[$285,000/($80,000 + $110,000)/2)] = 121.7 days, not (a) 73 days,

(c) 102.5 days, or (d) 84.5 days.

15. d. Decreasing the amount of inventory on hand will cause the

denominator to decrease, causing inventory turnover to increase.

Increasing sales will cause the numerator of the ratio to increase

(higher sales means higher COGS), thus causing inventory turnover

to increase even more. The other choices are incorrect because (a) in-

creasing the amount of inventory on hand causes the denominator of

the ratio to increase while the numerator stays the same, causing inven-

tory turnover to decrease; (b) keeping the amount of inventory on hand

constant but increasing sales will cause inventory turnover to increase

because the numerator of the ratio will increase (higher sales means

higher COGS) while the denominator stays the same, which will result

in a lesser inventory increase than decreasing amount of inventory on

hand and increasing sales; and (c) keeping the amount of inventory

on hand constant but decreasing sales will cause inventory turnover to

decrease because the numerator of the ratio will decrease (lower sales

means lower COGS) while the denominator stays the same.

16. d. FIFO cost of goods sold is the same under both a periodic

and a perpetual inventory system. The other choices are incorrect

because (a) LIFO cost of goods sold is not the same under a periodic

and a perpetual inventory system; (b) average costs are based on a

moving average of unit costs, not an average of unit costs; and (c) a

new average is computed under the average-cost method after each

purchase, not sale.

17. b. COGS = Sales ($150,000) − Gross profit ($150,000 ×

30%) = $105,000. Ending inventory = Cost of goods available for

sale ($135,000) − COGS ($105,000) = $30,000, not (a) $15,000,

(c) $45,000, or (d) $75,000.

*

*

2. (LO 3) Financial Statement Avisail Company reports net income of $80,000 in 2020. How-

ever, ending inventory was overstated $9,000. What is the correct net income for 2020? What effect,

if any, will this error have on total assets as reported in the balance sheet at December 31, 2020?

Determine correct income statement

amounts.

Solution

2. The overstatement of ending inventory caused cost of goods sold to be understated $9,000 and net

income to be overstated $9,000. The correct net income for 2020 is $71,000 ($80,000 − $9,000).

Total assets in the balance sheet will be overstated by the amount that ending inventory is over-

stated, $9,000.

3. (LO 4) At December 31, 2020, the following information was available for Garcia Company:

ending inventory $30,000, beginning inventory $42,000, cost of goods sold $240,000, and sales

revenue $400,000. Calculate inventory turnover and days in inventory for Garcia Company.

Compute inventory turnover and days

in inventory.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/accountingprinciplesthirteenthedition-230807181225-90dae868/75/Accounting-Principles-Thirteenth-Edition-pdf-321-2048.jpg)

![6-40 CHAPTER 6 Inventories

Instructions

a. Calculate the cost of the ending inventory and the cost of goods sold for each cost flow assumption,

using a perpetual inventory system. Assume a sale of 440 units occurred on June 15 for a selling

price of $8 and a sale of 360 units on June 27 for $9.

b. How do the results differ from the answers to E6.7 and E6.9?

c. Why is the average unit cost not $6 [($5 + $6 + $7) ÷ 3 = $6]?

E6.18 (LO 5) Information about Elsa’s Boards is presented in E6.5. Additional data regarding Elsa’s

sales of Xpert snowboards are provided below. Assume that Elsa’s uses a perpetual inventory system.

Date Units Unit Price Total Revenue

Sept. 5 Sale 12 $199 $ 2,388

Sept. 16 Sale 50 199 9,950

Sept. 29 Sale 59 209 12,331

Totals 121 $24,669

Instructions

a. Compute ending inventory at September 30 using FIFO, LIFO, and moving-average cost.

b. Compare ending inventory using a perpetual inventory system to ending inventory using a periodic

inventory system (from E6.5).

c. Which inventory cost flow method (FIFO, LIFO) gives the same ending inventory value under both

periodic and perpetual? Which method gives different ending inventory values?

E6.19 (LO 6) Shereen Company reported the following information for November and

December 2020.

November December

Cost of goods purchased $536,000 $ 610,000

Inventory, beginning-of-month 130,000 120,000

Inventory, end-of-month 120,000 ?

Sales revenue 840,000 1,000,000

Shereen’s ending inventory at December 31 was destroyed in a fire.

Instructions

a. Compute the gross profit rate for November.

b. Using the gross profit rate for November, determine the estimated cost of inventory lost in the fire.

E6.20 (LO 6) The inventory of Hang Company was destroyed by fire on March 1. From an examination

of the accounting records, the following data for the first 2 months of the year are obtained: Sales Reve-

nue $51,000, Sales Returns and Allowances $1,000, Purchases $31,200, Freight-In $1,200, and Purchase

Returns and Allowances $1,400.

Instructions

Determine the merchandise lost by fire, assuming:

a. A beginning inventory of $20,000 and a gross profit rate of 30% on net sales.

b. A beginning inventory of $30,000 and a gross profit rate of 40% on net sales.

E6.21 (LO 6) Kicks Shoe Store uses the retail inventory method for its two departments, Women’s Shoes

and Men’s Shoes. The following information for each department is obtained.

Women’s Men’s

Item Shoes Shoes

Beginning inventory at cost $ 25,000 $ 45,000

Cost of goods purchased at cost 110,000 136,300

Net sales 178,000 185,000

Beginning inventory at retail 46,000 60,000

Cost of goods purchased at retail 179,000 185,000

Instructions

Compute the estimated cost of the ending inventory for each department under the retail inventory

method.

*

Apply cost flow methods to perpetual

records.

*

Use the gross profit method to

estimate inventory.

*

Determine merchandise lost using

the gross profit method of estimating

inventory.

*

Determine ending inventory at cost

using retail method.

Excel](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/accountingprinciplesthirteenthedition-230807181225-90dae868/75/Accounting-Principles-Thirteenth-Edition-pdf-333-2048.jpg)